Arguably the greatest success story of the 1960s rock music era belonged to a man most people don’t recognize by name.

Certainly not by his given name — Harold Belsky — nor even by his professional name — Hal Blaine.

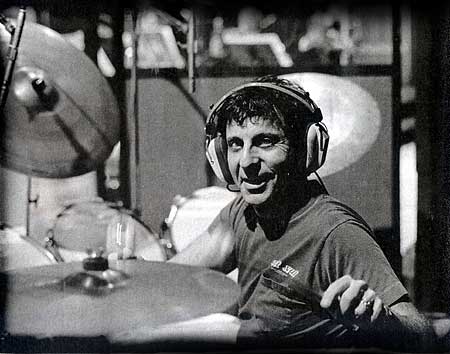

Since his death last week at age 90, you may have learned his name by reading any of the multiple articles, in print and online, that cataloged his extraordinary accomplishments. He has been recognized in his industry (and now, increasingly, by the public at large) as an unparalleled titan among that breed of musician that worked diligently behind the scenes, in the proverbial shadows. In the recording studios of Los Angeles, he played the drums in thousands of recording sessions between roughly 1960 and 1980, anonymously providing the backbeat for the hits of many hundreds of popular singers.

Since his death last week at age 90, you may have learned his name by reading any of the multiple articles, in print and online, that cataloged his extraordinary accomplishments. He has been recognized in his industry (and now, increasingly, by the public at large) as an unparalleled titan among that breed of musician that worked diligently behind the scenes, in the proverbial shadows. In the recording studios of Los Angeles, he played the drums in thousands of recording sessions between roughly 1960 and 1980, anonymously providing the backbeat for the hits of many hundreds of popular singers.

Name a hit single from the Sixties, and it’s very likely he was working the drum kit on the recording. The Beach Boys’ “Help Me, Rhonda”? Yep. Frank Sinatra’s “That’s Life”? Sure. Sonny and Cher’s “I Got You Babe”? Check. Elvis Presley’s “Return to Sender”? You bet. The Mamas and The Papas’ “California Dreamin'”? Uh-huh. The Ronettes’ “Be My Baby”? One of his best.

It’s truly unbelievable, the pervasiveness of Blaine’s work during that period. His skillful drum work can be heard (and, sometimes, barely heard, when called for) on records by a broad cross section of American musical artists, from The Fifth Dimension to The Byrds, from The Partridge Family to Elvis Presley, from The Grassroots to Neil Diamond, from Barbra Streisand to Jan and Dean.

It’s estimated that Blaine played on more than 6,000 songs, 150 of which became Top Ten hits on the Billboard charts, and 40 of which reached Number One.

Here’s an especially remarkable fact: Blaine’s drums were featured on six consecutive Record of the Year Grammy winners — “A Taste of Honey” by Herb Alpert and The Tijuana Brass (1966), “Strangers in the Night” by Frank Sinatra (1967), “Up, Up and Away” by The Fifth Dimension (1968), “Mrs. Robinson” by Simon and Garfunkel (1969), “Aquarius (Let the Sunshine In)” by The Fifth Dimension (1970) and “Bridge Over Troubled Water” by Simon and Garfunkel (1971).

How did this happen? How could one drummer end up manning the skins on so many hit records? To comprehend this, you have to understand how the record-making process worked during that era:

An artist’s manager and/or record label rep would learn of a song, usually as a demo tape submitted by a songwriter, and wanted their artist to record it and release it. (This often had to happen quickly, before someone else beat them to it.) Studio time would be booked, and a producer would be hired to oversee the recording session.

The producer was usually the guy holding all the cards. It was up to him to decide the arrangement, the tempo and, most important, the musicians to use in order to get the best recording in the most efficient use of time. This usually meant hiring guitarists, bass players, keyboard players and drummers who were known for their ability to intuitively  know exactly what was called for in a given song or recording.

know exactly what was called for in a given song or recording.

In Los Angeles studios between roughly 1962 and 1972, that meant the producer wanted Hal Blaine on the drums. There was, quite simply, no question about it. Whether you wanted a snappy 4/4-time backbeat, a syncopated jazz touch, or just some subtle brush work, there was no one easier to work with, no one better qualified.

How did Blaine feel about this? Last year, as he was receiving a Lifetime Achievement Award at the Grammys for his extraordinary body of work, he said, “I felt at the time as If I had fallen into a vat of chocolate. It was a wonderful, wonderful thing to be asked to play drums for so many different singers and bands. I was truly living my dream.”

Blaine was, by all accounts, the unofficial ringleader of an unofficial group of LA-based studio musicians who came to be known as The Wrecking Crew. Several dozen top-notch players could justly claim informal membership in this confederation, but the core group consisted of Blaine (drums), Carol Kaye (bass), Larry Knechtel (keyboards, bass), Tommy Tedesco (guitar), Glen Campbell (guitar), Steve Douglas (sax), Earl Palmer (drums), Mike Rubini (keyboards), Joe Osborn (bass), Louie Shelton (guitar), Jim Gordon (drums), Leon Russell (keyboards), Billy Strange (guitar) and Jack Nitzsche (arranger/conductor).

There had been an older version of The Wrecking Crew in the 1940s and 1950s — a more buttoned-down group of studio musicians who liked the nickname “The First-Call Gang.” They were, indeed, the first ones called when a top performing artist wanted to record a new song or album. These were typically the “easy listening” singers who offered the more standard, strings-laden torch songs of those days — Vic Damone, Pattie Page, Johnny Mathis, Rosemary Clooney, Perry Como.

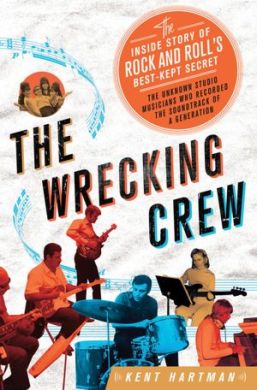

The studio pros who provided musical backing then were “the blue-blazer-and-necktie,  by-the-book, time-clock-punching men who had cut their teeth playing on Big Band records, movie soundtracks and early TV shows,” as writer Kent Hartman put it in “The Wrecking Crew,” his authoritative 2012 book. “They loathed everything about rock and roll. To them, this new music was appallingly primitive, and most refused to play it. In their minds, their careers had been built on decorum and sophistication, not on wearing T-shirts and blue jeans to work while bashing out what they felt were simplistic three-chord rhythm patterns over and over. ‘That kind of thing is surely going to wreck the business,’ they would say.”

by-the-book, time-clock-punching men who had cut their teeth playing on Big Band records, movie soundtracks and early TV shows,” as writer Kent Hartman put it in “The Wrecking Crew,” his authoritative 2012 book. “They loathed everything about rock and roll. To them, this new music was appallingly primitive, and most refused to play it. In their minds, their careers had been built on decorum and sophistication, not on wearing T-shirts and blue jeans to work while bashing out what they felt were simplistic three-chord rhythm patterns over and over. ‘That kind of thing is surely going to wreck the business,’ they would say.”

Blaine, known for his easygoing manner and infectious sense of humor, chuckled when he heard this. “They think we’re wrecking the industry? Well, okay then, we’ll call ourselves The Wrecking Crew!”

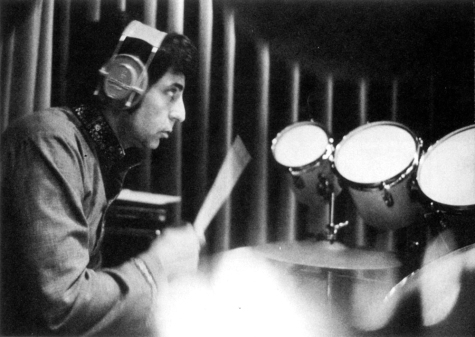

They worked tirelessly, sometimes up to eight sessions a day. They recorded movie and TV theme songs and film soundtracks, and played the music for some TV commercials as well. Mostly, though, they recorded lots and lots of hit singles, and lesser-known album tracks, for the era’s biggest stars.

In some cases, their involvement was meant to be kept secret. The Beach Boys, for example, had played their own instruments on their earliest records (1961-1963), which had basic, simple arrangements. But once Brian Wilson heard what producer Phil Spector was accomplishing with studio musicians on his “Wall of Sound” recording process on tracks like The Crystals’ “He’s a Rebel” and The Ronettes’ “Be My Baby,” he wanted Beach Boys tracks to have that same degree of professionalism. On Wilson’s  more sophisticated compositions like “California Girls,” “Good Vibrations,” “Sloop John B” and “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” he brought in Blaine and his compatriots to substitute for his Beach Boys cohorts in the studio, and the listening public was none the wiser.

more sophisticated compositions like “California Girls,” “Good Vibrations,” “Sloop John B” and “Wouldn’t It Be Nice,” he brought in Blaine and his compatriots to substitute for his Beach Boys cohorts in the studio, and the listening public was none the wiser.

“Hal Blaine was such a great musician and friend that I can’t put it into words,” Wilson said the other day in a tweet that included an old photo of him and Blaine sitting at the piano. “Hal taught me a lot, and he had so much to do with our success. He was the greatest drummer ever.”

Blaine had wanted to be a professional drummer since he was a boy. With every musical act that passed through his Massachusetts home town, young Hal would position himself close to the bandstand so as to watch every movement the drummer made. These were typically Big Band drummers — Gene Krupa, Buddy Rich, Dave Tough — and they were his heroes, the coolest “hepcats” around.

In his late teens, Blaine learned drums in Chicago from the great Roy Knapp, who had taught Krupa and others, and in his early ’20s, Blaine played in Chicago strip clubs and with small jazz combos, eventually touring and recording with Count Basie’s outfit, Pattie Page and teen idol Tommy Sands. Unlike his jazz drummer counterparts, Blaine took a liking to rock and roll, not only because the studio sessions proved lucrative but because he enjoyed it and understood the kind of drumming parts the producers were looking for.

Blaine’s acumen was not in showiness but in capability. “I was never a soloist, I was an accompanist,” he told Modern Drummer magazine in 2005. “That was my forte. I never had Buddy Rich chops. I never cottoned to the Ginger Baker drum solos.”

He always seemed to know what a song needed, and sometimes he stumbled on to it by happenstance. One of his signature moments — the attention-grabbing “on the four” solo (bum-ba-bum-BOOM) that launched the 1963 Phil Spector-produced hit “Be My Baby” —  came about when he accidentally missed a beat while the song was being recorded and improvised by only playing the beat on the fourth note.

came about when he accidentally missed a beat while the song was being recorded and improvised by only playing the beat on the fourth note.

“And I continued to do that,” Blaine recalled. “Phil (Spector) might have said, ‘Hey, do that again.’ Somebody loved it, in any event. It was just one of those things that sometimes happens.”

Another iconic contribution Blaine made was during the recording of Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Boxer” in 1969. “I was going for what I later called a ‘cannonball-like’ sound, something to bruise the song, which I felt was too sweet, too much like a lullaby. The producer, Roy Halee, heard it and had an idea. He set me up with my kit in an empty elevator shaft. When the music got to the ‘Lie-la-lie’ part, I hit the drums as hard as I could.” The resulting effect was indeed like a gunshot, a cannonball blast.

By the 1970s, producers began losing some of their authority as rock bands rightly insisted that the group’s members should be the ones to play the guitar, bass, keyboard and drum parts on their records. There would still be the prominent singers (Streisand, The Carpenters, John Denver) who needed studio musicians to provide the professional instrumental backup on their records, but by the 1980s, demand for studio musicians dwindled. The advent of electronic drum machines and other techno options made guys like Blaine all but obsolete.

He continued to appear occasionally at symposiums and workshops, and on TV talk shows, well into his ’80s. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2000 with four other Wrecking Crew partners, and he was prominently featured in the 2008 documentary “The Wrecking Crew,” directed by Denny Tedesco (son of Tommy Tedesco), and in Hartman’s 2012 book.

He continued to appear occasionally at symposiums and workshops, and on TV talk shows, well into his ’80s. He was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2000 with four other Wrecking Crew partners, and he was prominently featured in the 2008 documentary “The Wrecking Crew,” directed by Denny Tedesco (son of Tommy Tedesco), and in Hartman’s 2012 book.

But I keep coming back to the head-shaking list of songs on which Blaine is listed as drummer. “Mr. Tambourine Man” (The Byrds). “These Boots Are Made For Walking” (Nancy Sinatra). “Half-Breed” (Cher). “You’re the One” (The Vogues). “Secret Agent Man” and “Poor Side of Town” (Johnny Rivers). “Johnny Angel” (Shelley Fabares). “Another Saturday Night” (Sam Cooke). “Windy” and “Along Comes Mary” (The Association). “Wedding Bell Blues” and “One Less Bell to Answer” (The Fifth Dimension). “River Deep, Mountain High” (Ike and Tina Turner). “Love Will Keep Us Together” (The Captain and Tennille). “Let’s Live for Today” (The Grassroots). “If I Were a Carpenter” (Bobby Darin). “MacArthur Park” (Richard Harris). “Ventura Highway” (America). “Dizzy” (Tommy Roe). “Annie’s Song” (John Denver). “This Diamond Ring” (Gary Lewis and The Playboys). “Wichita Lineman” and “Galveston” (Glen Campbell). “Kicks” (Paul Revere and The Raiders). “The Way We Were” (Barbra Streisand). “The Little Old Lady From Pasadena” (Jan and Dean). “(They Long to Be) Close to You” and “Top of the World” (The Carpenters). “Monday Monday” and “I Saw Her Again” (The Mamas and The Papas). “Everybody Loves Somebody” (Dean Martin). “Cracklin’ Rosie” and “Song Sung Blue” (Neil Diamond).

Are you kidding me?!

Blaine himself always loved to tell the story about the day he met Bruce Gary, drummer for the late ’70s British pop band The Knack (“My Sharona”). “He was telling me how much he loved American pop songs of the 1960s, and he had started researching who the different drummers were on the various records. He told me he was almost disappointed when he discovered that a dozen of his favorite drummers were me!”

We are pretty proud of Tommy Tedesco here in Western New York. Fellow readers, make sure you see the documentary if you get the chance; it’s fascinating. Nice job, Bruce.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Budd!

LikeLike

He was “the beat” to be reckoned with. Can’t think of anyone comparable except for maybe Benny Benjamin with the Funk Brothers.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Can’t imagine how cool it must have been to be involved in so many sessions with so many different stars!

LikeLike

I was reading up on Carol Kaye this week and she reckoned that Hal Blaine coined the term “Wrecking Crew” when he wrote his autobiography in the 1990s.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I had heard he thought of it many years earlier, but you may be right…

LikeLiked by 1 person

In Wikipedia it says: “Kaye was the sole regular female member of The Wrecking Crew (though she has said the group were never known by this name, which was later invented by Blaine)”

LikeLike

You deserve a Hal Blaine drumroll for writing this one up.

Many thanks!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks Ted! As a drummer, you’re already a Hal Blaine fan, but it’s high time everybody else is too!

LikeLike