Pretty good at making bad decisions

In life, there are so many factors that might lead to making ill-advised choices that it’s a wonder we make any good decisions at all.

Arrogance and overconfidence cause us to do things we wouldn’t otherwise do. So can stubbornness, inflexibility and apathy. Overwhelming emotions — fear, anger, greed, lust, guilt — can affect our thinking at precisely the wrong time. Impulsiveness, immaturity or ignorance can manipulate us in damaging ways when we need to make decisions with far-ranging consequences.

In the business world, these things can influence those in leadership positions, and the ramifications can affect the lives and livelihoods of hundreds, even thousands, of others.

For half a century, the rock music business has been populated with misguided executives and decision makers (sometimes the artists themselves) who chose courses of action which, over time, proved to be wrong-headed, even calamitous. Rolling Stone recently compiled a catalog of 30 stupid decisions in rock history, and from that list, I selected a dozen that struck me as particularly noteworthy.

******************************

Decca Records rejects The Beatles

Manager Brian Epstein had tried in vain to secure a record contract for The Beatles with a half-dozen different companies in 1961 but had no takers. Decca Records, to their credit, was the first to invite them in for a commercial test audition, at which they performed 15 songs, including three Lennon-McCartney originals. A month later, Decca sent word to Epstein that they weren’t interested, saying, “The Beatles have no future in show business. Guitar groups are on the way out.” It’s unclear which individual at Decca had the final say on rejecting the group that would soon change the face of pop music, but there’s no question Decca missed out on many millions because someone there couldn’t hear the potential in those early recordings. Decca ended up signing The Tremeloes instead, who scored a few hits in the ’60s but had only a fraction of the impact and influence The Beatles had. (A couple months later, George Martin at EMI Records’ Parlophone label liked what he heard and signed the Liverpool foursome, and we all know how their chemistry worked out.)

Bands refuse to be on “Woodstock” album or film

More than 30 musical acts performed at the Woodstock Music and Arts Fair in August 1969 in upstate New York, and several of them — especially Crosby, Stills and Nash, Joe Cocker, The Who, Santana and Sly and the Family Stone — benefited in a big way from their participation because they agreed to be included in the Michael Wadleigh documentary film and the triple-album release, which were both big commercial successes. Other bands, however, made the boneheaded decision to refuse permission to use their performances on the record or in the movie. Blood, Sweat and Tears, Creedence Clearwater Revival, Mountain and The Grateful Dead all said no, which denied them the exposure to the much broader audience that saw the film and bought the album. Leslie West, Mountain’s guitarist, said the band played a strong, hard-rocking set on Day Two, but he never got a satisfactory answer as to why the group’s manager chose not to sign off on the contract. “Who knows? Maybe he asked for too much money,” he said years later, no doubt wondering how a different decision might have changed the band’s career arc in the ensuing years.

The Artist Now Known as an Unpronounceable Symbol

Prince was a wildly prolific artist, recording many dozens of songs and compiling them into albums, but Warner Brothers, his record company, was reluctant to “flood the market” with too many releases and held them back. By 1993, Prince said he felt like “a slave” and, in hopes of nullifying his contract, changed his name to a “Love Symbol” that combined the symbols for man and woman with something resembling a trumpet. Warner Bros. started calling him “The Artist Formerly Known as Prince,” and the whole thing ended up confusing and/or alienating some of his fans, and sales suffered. By 2000, he changed his name back to Prince and admitted the stunt hadn’t worked out as intended.

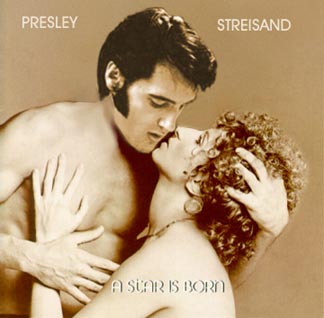

Elvis misses out on “A Star is Born” opportunity

In 1976, singer/actress Barbra Streisand and then-partner Jon Peters were eager to revive the Hollywood classic “A Star is Born,” reimagining it for the music business instead of the film industry. Streisand would play the budding young singer on her way up, and she and Peters set their sights on Elvis Presley to play the part of the past-his-prime rock star. Presley, who had made a handful of decent movies amidst a raft of bombs throughout the ’60s, allegedly showed real interest in the project, but his notoriously greedy, controlling manager, Colonel Tom Parker, stood in the way. Parker decided to ask for too much money and insisted that Presley receive top billing, and that the story must tone down the characterization of of Presley as “washed up.” The producers, put off by these excessive demands, turned their attentions elsewhere, eventually casting singer Kris Kristofferson instead. The film and soundtrack album were both enormous box office and pop chart successes, which would have been a real shot in the arm for Presley, who needed a win at that point in his life. Less than a year later, Presley was dead.

Roger Waters underestimates the rest of Pink Floyd

As the runaway successes of “Dark Side of the Moon,” “Wish You Were Here,” “Animals” and “The Wall” made Pink Floyd one of the top rock acts in the world, relations between chief songwriter Roger Waters and the other band members deteriorated. By 1984, David Gilmour, Nick Mason and Rick Wright found Waters’ ego insufferable, and Waters decided he’d had enough of their lack of gratitude for his talents and chose to leave for a solo career. He felt he WAS Pink Floyd, and without him, the group would simply fold. But he miscalculated how much cachet the Pink Floyd brand had, and the fact that the group had been essentially a faceless entity. Many fans didn’t know or care about a solo career from any of these guys, just “more Pink Floyd.” Consequently, when they went on tour simultaneously in 1987, ticket sales were tepid for Waters while the band sold out arenas everywhere. Waters remained bitter for decades and has remained estranged from Pink Floyd except for only a couple of one-off appearances.

“Sergeant Pepper: The Musical”

In 1978, Peter Frampton and The Bee Gees were riding high on two of the best selling albums of all time: “Frampton Comes Alive” and the “Saturday Night Fever” soundtrack. Bee Gees manager Robert Stigwood convinced the two superstar acts to join forces for a “jukebox musical” film loosely based on the songs from The Beatles’ watershed 1967 LP “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” They could’ve said no, but they went along with it, despite a lame script and substandard re-imaginings of Beatles songs for the soundtrack. Critics pounced, and a case could be made that the reputations of both acts never fully recovered from the ill-advised project. They could’ve said, “We goofed on that one,” but the damage was done, thanks to pre-release comments liked this one from Robin Gibb: “Kids today don’t know the Beatles’ ‘Sgt. Pepper,’ and when they see the film and hear us doing it, that will be the version they relate to and remember. The Beatles no longer exist as a band and never performed ‘Sgt. Pepper’ live, so when ours comes out, it will be as if theirs never existed.” The arrogance was breathtaking.

The Beach Boys take a pass on Monterey Pop

The Monterey Pop Festival, which preceded Woodstock by two years, had a little something for everybody: psychedelia (Jimi Hendrix, Grateful Dead), folk rock (Simon and Garfunkel, The Byrds) sunny pop (The Mamas and The Papas, The Association), blues (Janis Joplin), jazz (Hugh Masakela) and soul (Otis Redding). It was a gentle, tolerant audience eager to hear a broad array of groovy music. Even though Brian Wilson served on the festival board, and “Good Vibrations” had been a #1 hit only six months earlier, The Beach Boys reached the curious conclusion that they somehow wouldn’t fit in and chose to take themselves out of the lineup. Mike Love has said they feared they might seem outdated when seen up against the edgier, newer acts of that “Summer of Love.” They still had good music ahead of them, but they missed a prime chance to claim their place in the pantheon and still be considered truly hip members of the rock/pop music scene rather than an oldies act in the years ahead.

Pioneer rocker takes 13-year-old cousin/bride on European tour

Jerry Lee Lewis was right up there with Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly and Elvis as one of the trailblazers of rock ‘n’ roll in 1955-1958. “Great Balls of Fire,” “Breathless” and “Whole Lotta Shakin’ Going On” became iconic musical milestones of that era. But Lewis seriously misjudged the public’s mood and moral judgment when he headed off for his first tour of Great Britain. The press quickly learned that the woman by his side, Myra, was not only his third wife in six years, she turned out to be his first cousin…and she was only 13. In his home state of Louisiana, this might’ve been legal and no big deal, but in England and the rest of the United States, this was shocking and unacceptable. The tour was canceled after only a couple of shows, and Lewis struggled mightily on the charts and on the road for many years afterwards. He eventually had some success as a country artist and on the ’50s nostalgia package tours, but the scandal followed him for the rest of his days.

The Buggles join Yes

By 1979, with New Wave and disco holding sway on the charts, progressive rock as a genre seemed to be way out of fashion, which posed a dilemma within the ranks of Yes. Vocalist Jon Anderson and keyboardist Rick Wakeman preferred lighter, more folk-oriented material, while guitarist Steve Howe, bassist Chris Squire and drummer Alan White leaned toward harder arrangements, which proved to be an irreconcilable difference that sent Anderson and Wakeman packing. Yes’s manager, a guy named Brian Lane, was also managing an act called The Buggles, who had a big New Wave hit in the UK with “Video Killed the Radio Star.” Since Yes had upcoming tour dates and needed a new album out beforehand, Lane suggested bringing Buggles principals Trevor Horn and Geoff Downes into Yes to flesh out and update the group’s sound. The resulting LP “Drama” was an unwelcome departure, and when Yes took the stage with two new people out front, fans balked. “It was a nightmare,” conceded Squire, and Yes broke up for several years. When they reformed in 1983, Anderson was back as lead singer.

Bob Dylan’s “Self-Portrait”

For the first decade of his distinguished career, Bob Dylan wrote and recorded game-changing songs featuring profound lyrics that captured the changing times better than any other artist. By 1970, though, he was sick to death of the “voice of a generation” label that had been pinned on him, so he made a drastic move that can only be viewed as foolhardy in retrospect. “I said, ‘Well, fuck it, I wish these people would just forget about me,'” he said in 1984. “I wanna do something they can’t possibly like, they can’t relate to at all.” The result was “Self Portrait,” a double album comprised almost entirely of covers made almost unlistenable by uncharacteristic strings and choirs. He said it was intended as a cruel joke but it backfired when the press and the public crucified him for it. “The album went out there, and the people said, ‘This ain’t what we want,’ and they got more resentful.” It took him a few years to fully rebound from that move.

The Grammys overlook bonafide artists for one-hit wonders

Over the years, those who cast votes in The Grammys have shown themselves to be hopelessly out of touch, and nowhere more so than in the Best New Artist category. Too often, this award has gone to someone who had one popular hit single and then was barely ever heard from again. In the 1970s, this happened almost every year, as major rock bands who were truly groundbreaking and far more worthy were passed over for a “flavor of the month” group that had one big hit and then vanished. In 1977, it was Starland Vocal Band (“Afternoon Delight”) over Boston; in 1978, it was Debby Boone (“You Light Up My Life”) over Foreigner. The most embarrassing example came in 1979, when A Taste of Honey (“Boogie Oogie Oogie”) inexplicably triumphed over legitimate contenders Elvis Costello, The Cars and Toto. Good grief, what a colossal error.

Hells Angels picked to provide security at Altamont concert

To close out their U.S. tour at the end of 1969, The Rolling Stones hoped to capitalize on the rock-festival vibe then in vogue by staging a free concert in San Francisco’s Golden Gate Park, but they hadn’t planned sufficiently and were forced to move the event to Altamont Speedway, an auto racing venue 40 miles east of Oakland. Inadequate water supplies, food and toilet facilities made for a surly mood, and with a stage barely three feet high, security became a crucial component. Bay Area bands like Jefferson Airplane and The Grateful Dead suggested the violence-prone Hells Angels, a dangerous idea by all accounts, and the Stones, as headliners, inexplicably signed off on it. The biker group, juiced up on too much booze and drugs, manhandled concertgoers and beat one man to death in view of a film crew as Mick Jagger and the band played “Under My Thumb.” It was a horrible decision that led many observers to label the event “the end of the Sixties peace-and-love dream.”