When it’s time for leaving, I hope you’ll understand

Throughout the 1960s, most rock bands had two guitarists — a rhythm guitarist who played chords and established the song’s basic structure, and a lead guitarist who provided the multi-note solos that soared above it all and often stole the spotlight.

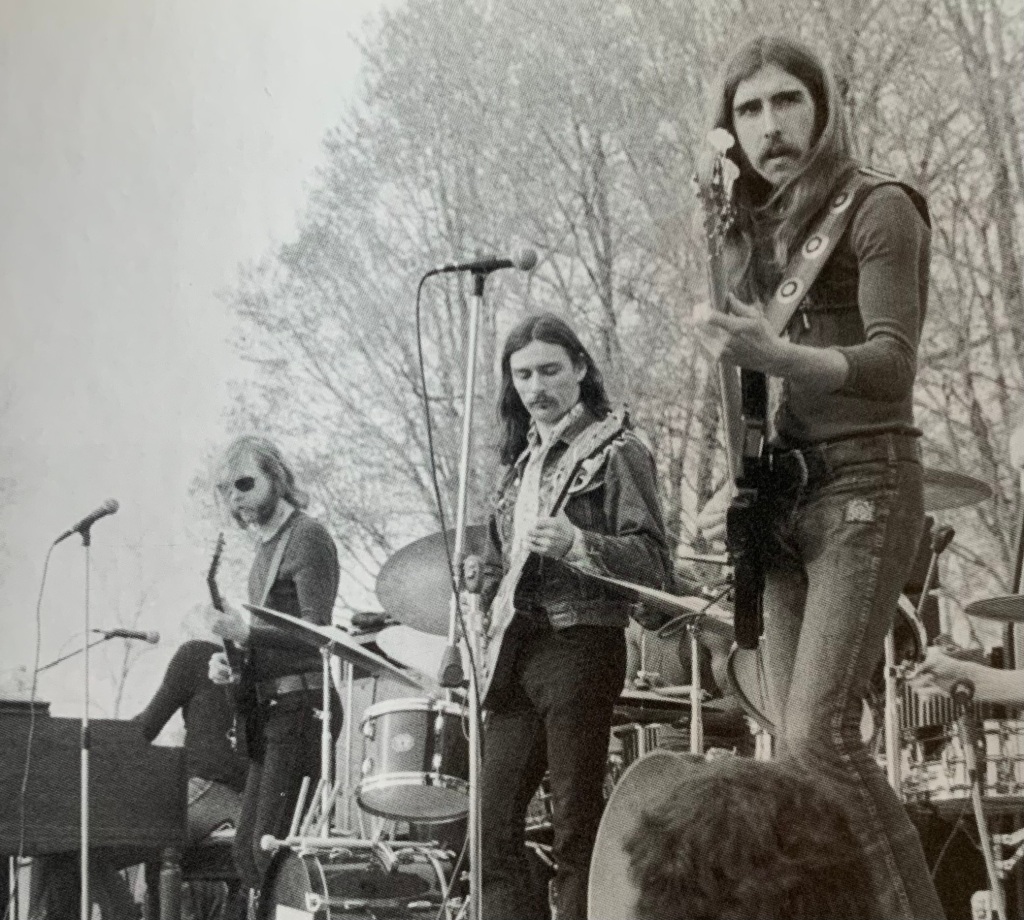

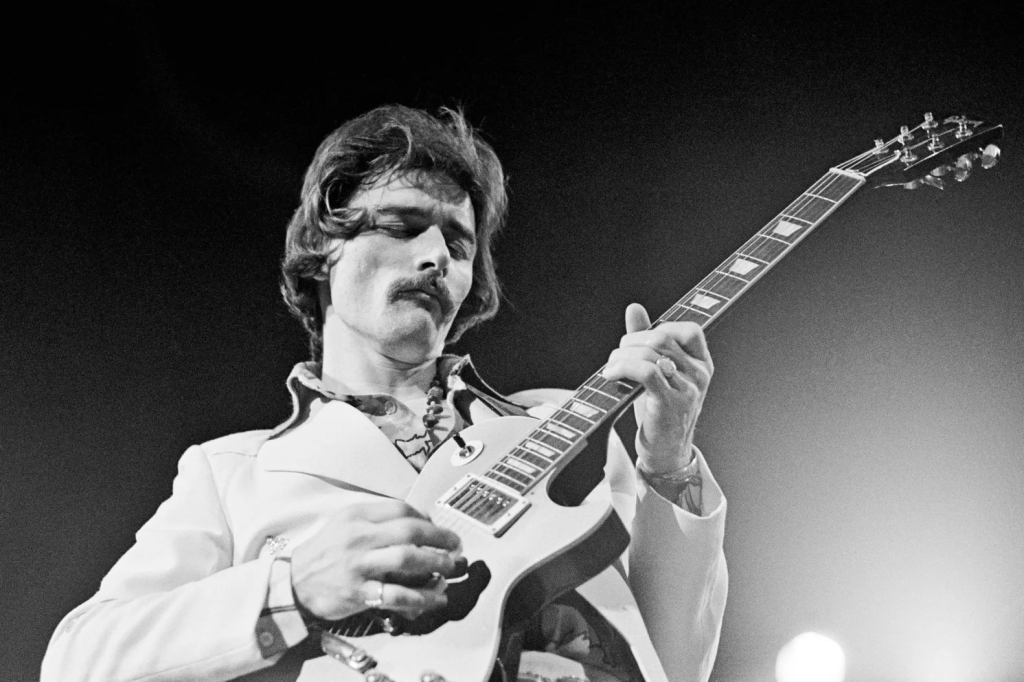

Then in 1969 came The Allman Brothers Band, which featured two supremely talented lead guitarists in Duane Allman and Dickey Betts. One would play lead while the other supported on rhythm, then they’d switch roles. Most impressive, though, was when they played lead guitars simultaneously. In the studio, these passages were precise and rehearsed, but on stage (and captured on live albums), Allman and Betts were master improvisationalists. Hearing the way these guitarists played off one another, giving each other room while adding a harmony solo to the melody solo, was truly special, and it was a primary reason the Allman Brothers were regarded, for a while, as the best band in the country.

Duane Allman died shockingly young, at 24, in a motorcycle accident just as the band was becoming successful. And now Dickey Betts has died as well, succumbing to cancer and pulmonary disease at age 80 last week.

As Betts put it in “One Way Out,” the 2014 biography of the band, “Because of the name of the band, a lot of people assumed Duane was the lead player and I was the rhythm guy. He was so charismatic and I was more laid back then. But he went out of his way to make sure people understood we were a twin-guitar band. ‘That was Betts who played that solo, not me,’ he would say. ‘We have two lead guitarists in this damn band!’

“Duane and I talked about how scared we got whenever the other played a really great solo. But then he’d chuckle and say, ‘This isn’t a contest. We can make each other better and do something deep.””

*************************

Betts was drawn to music at a young age, learning ukulele at age five, then mandolin, banjo and guitar as his hands got bigger. His musical family listened to a lot of country music, Western swing and bluegrass, and as a teen, Betts became fascinated with rock ‘n’ roll and the blues. He played many dozens of gigs with different rock bands all over Florida and up the East Coast. In 1967, he met bassist Berry Oakley and formed Second Coming.

“In our band, Berry and I would take a standard blues and rearrange it,” Betts said. “We were really trying to push the envelope. We wanted to play the blues in a rock style like what Cream and Hendrix were doing. We liked taking some of that experimental stuff and putting a harder melodic edge to it. One of our favorite things to do was to jam in minor keys, experimenting freely with the sounds of different minor modes. We allowed our ears to guide us, and this type of jamming eventually served to inspire the writing of songs like ‘In Memory of Elizabeth Reed.’

“But we weren’t some garage band. We were a nightclub band. We had brought ourselves up in the professional world actually playing in bars, and that gives you a lot more depth. Duane and his brother were doing the same thing, so we all had a lot of miles under our belt when we met, despite our ages.”

When The Allman Brothers Band came together in 1968, they featured two drummers (Butch Trucks and Jai Johanny “Jaimoe” Johnson), bassist Oakley, Gregg Allman on vocals and organ, and the Betts-Allman guitar attack. They focused on blues with a rock edge, and while their self-titled debut album in 1969 performed poorly on the charts, it established them as a force to be reckoned with.

Betts’ first attempts at songwriting, which came on their next LP, “Idlewild South,” were impressive indeed. “Revival” opened the album with a burst of uptempo optimism — “People can you feel it, love is everywhere” — while the instrumental track “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed” built on an infectious riff and showcased both Betts’ and Allman’s complementary styles.

But the band knew that something was missing from those first albums. They didn’t capture the excitement and ferocious output you’d hear when they played in concert, and they knew they needed their next release to be a double live album, where they had the chance to stretch out and show their phenomenal skills as an improvisational jam band.

“At Fillmore East” was that album, produced by the great Tom Dowd from performances at the famed New York City venue in March 1971, featuring seven extended songs over four sides. In particular, “Whipping Post” and “Liz Reed” were a revelation, showing how the guitarists had been inspired by freeform jazz greats like John Coltrane and Miles Davis, and the album ended up peaking at #13.

Said Betts: “It’s very hard to go freestyle with two guitars. It’s easy to sound like two cats fighting if you’re not careful. Duane would almost always wait for me to come up with a melody and then he would join in on my riff with the harmony. A lot of his notes are not the notes you would choose if you sat down to write it out, but they always worked. Our band came along at a wonderful time for improv, and we felt free to just play and work things out on the fly. Doing that gave it all a certain spark.”

They toured relentlessly and also continued writing and recording new material for their next album. Betts wrote the sunny, joyous “Blue Sky,” a love song to his then-wife, a Native American named Sandy Blue Sky, “but I decided to drop the pronouns and make it like I was thinking of the spirit, like I was giving thanks for a beautiful day. It made it broader and more relatable. It was a bad marriage, but it led to a great song.”

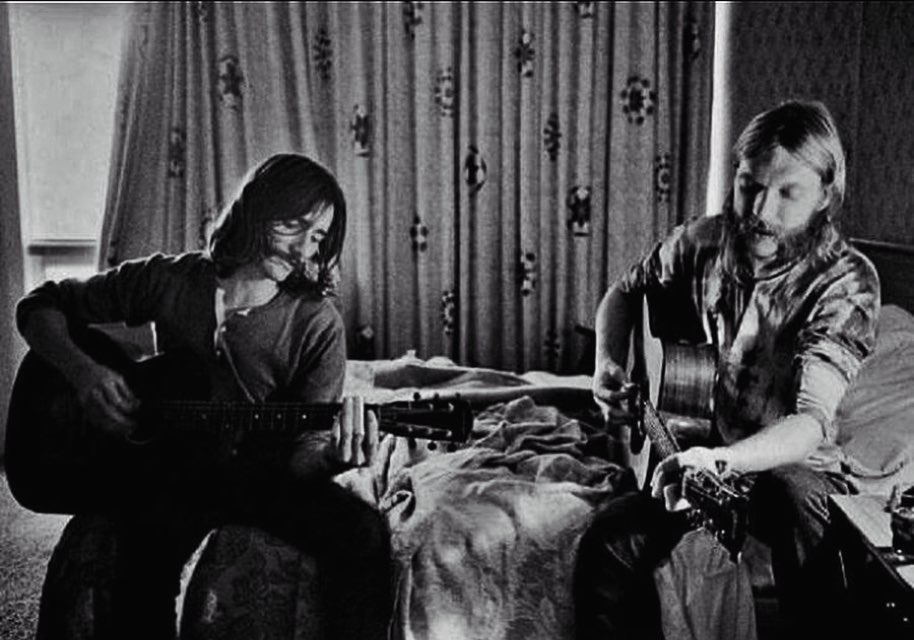

Betts said he and Allman often played acoustic guitars together backstage and in hotel rooms and buses, working out things they would later play electrically. “Little Martha,” a brief instrumental duet on Dobro guitars, came out of that.

Then, as the album was nearing completion, disaster struck. In a flash, Duane Allman, the band’s spark plug and spiritual leader, was gone. “We thought about breaking up and all forming our own bands,” said Betts, “but the thought of just ending it and being alone was too damn depressing.”

Thom Doucette, harmonica player and Duane’s confidant, noted, “It was kind of a leaderless operation there for a while. It very easily could’ve ended right there, but Betts pulled it out of the fire. Dickey’s personality and ego were pretty big, so he sort of took over. Someone had to, and Gregg hated responsibility and confrontation, and didn’t want to do it.”

The album, “Eat a Peach,” reached #4 and included both live and studio tracks, both with and without Duane’s contributions. On the road, the group proceeded as a five-piece, though Betts found it frustrating. “I had to learn to play Duane’s slide guitar parts, and we no longer had that dual guitar thing going. But we got through it by just playing, all the time. It’s all we knew how to do, and it’s what Duane would’ve wanted.”

The entire band tended to be excessive in their use of drugs and alcohol, but Oakley took Duane’s death particularly hard, diving deeper into the escape they provided. When he was killed in October 1972 under eerily similar circumstances, again the remaining members were faced with how to proceed. As Betts put it, “We found another bass player in Lamar Williams, but replacing Duane with another guitarist was simply out of the question.”

The answer, they found, lay in using a different instrument as the second lead: the virtuoso keyboard work of Chuck Leavell, who’d been playing with Dr. John. “When we added Chuck, it gave us a new wrinkle that energized us,” said Betts. “I’m not sure the band would’ve lasted as long as it did if it weren’t for Chuck. He was such a strong player.”

Betts, meanwhile, hit his stride as a songwriter, composing four of the seven tracks that comprised their 1973 album “Brothers and Sisters,” which reigned as #1 in the US for two weeks that autumn. The galloping “Southbound,” the front-porch country blues track “Pony Boy” and the exhilarating instrumental “Jessica” (with Leavell featured prominently) showed the diversity of Betts’ musical influences. His leanings toward country music manifested themselves most famously on “Ramblin’ Man,” which peaked at #2 as their highest charting single ever.

The song initially met some resistance from within. Drummer Butch Trucks recalled, “We knew ‘Ramblin’ Man’ was a good song, but it didn’t sound like us. It was too country to even record. But we made a demo to send to Merle Haggard or someone, and ended up getting into that long guitar jam (with guest guitarist Les Dudek adding the dual lead), which kind of fit us. So we put it on the album after all, and it ended up being our biggest hit.”

The fame that came with that album and single proved to be a double-edged sword. It made them a bigger concert draw than ever, packing arenas, stadia and festivals, but it also ramped up the partying and internal tension. For his part, Betts dipped his toe in solo waters with the country-heavy “Highway Call” LP in 1974, while Gregg Allman became more withdrawn and distracted by his own solo album (“Laid Back”) and tour, and a whirlwind relationship with pop star Cher. When he was threatened with prison on drug charges, he chose immunity by testifying against his roadie/drug dealer, which left such a bad taste that the band broke up in 1976.

A self-described workaholic during that period, Betts soldiered on with a new band and album, “Dickey Betts & Great Southern,” which saw Betts teaming up with guitarist Dan Toler on seven songs all written by Betts, notably the seven-minute piece “Bougainvillea.” A second Great Southern LP, “Atlanta’s Burning Down,” followed.

When Allman and Betts mended fences to reunite The Allman Brothers Band in 1979, it would be with Toler and bassist David Goldflies in the lineup in place of Leavell and Williams, who chose not to participate. The group came storming back with the strong “Enlightened Rogues” album, which made the US Top Ten, but again, there were storm clouds on the horizon, this time because of new record label demands and changing tastes in the music industry.

“When the music trend started turning away from blues-oriented rock towards more simple, synthesizer-based dance music arrangements,” Betts said, “the suits at Arista Records started pushing us hard in that direction, but we were never able to do that convincingly, mostly because we didn’t want to. Sure, we wanted a hit, but not if we had to make concessions. We broke up in ’82 because we decided we just better back out, or we would ruin what was left of the band’s image.”

Betts and Allman each kept their tools sharp through the Eighties by playing clubs with their own bands, and when the 4-LP box set “Dreams” was released in 1989 to commemorate the Allman Brothers’ 20th anniversary, the time seemed right to try again.

The arrival of the classic rock radio format created a favorable climate, as did the emergence of blues guitar virtuoso Stevie Ray Vaughan. “He opened the whole thing up,” said Betts. “He just would not be denied, and kept making those traditional urban blues records, and people got to appreciating the blues again. We didn’t want to record without touring first, but it was hard to tour without a record to support and generate interest. The box set took care of that.”

With both Trucks and Jaimoe back on drums, and Betts’ colleagues Warren Haynes and Allen Woody on slide guitar and bass, the band was reborn a third time, churning out three new studio albums in four years (“Seven Turns,” “Shades of Two Worlds” and “Where It All Begins”), liberally sprinkled with great Betts songs. The group performed nearly 100 dates annually, and not only were original fans thrilled to have the group back in the picture, but a new generation of listeners embraced their music as well.

Still, as always with this star-crossed band, problems surfaced. First Allman and then Betts fell victim to their own addictions and excesses, sometimes missing shows because of an inability to perform (Allman) or a mercurial temper and difficult ego (Betts).

“Dickey was capable of being really great, knowledgeable about all sorts of things, musical genres, art, news of the world, all of that,” said Danny Goldberg, the band’s manager for a spell. “But he was also capable of being really mean and physical, mostly when he was drinking. People were scared of him.”

In 2000, Betts lost two close friends within a few days of each other, which threw him for a loop and exacerbated his demons. Betts became so difficult to work with that the rest of the band felt they had no choice but to move on without him. Sadly, he never performed nor recorded with his old bandmates again after that.

In the years since, Betts stayed as active as his deteriorating health would allow, playing clubs and releasing a handful of live albums on smaller labels. When Allman was near death in 2017, working on one last album, he contacted Betts and asked him to join the sessions, but time ran out before that could happen.

Betts mellowed quite a bit in his final years, refusing to badmouth Allman or other members in the press. He was more than willing to concede his own part in the estrangement that plagued his relationships. “Substance abuse is an occupational hazard of being a musician,” he reflected. “It’s like working in an industrial waste factory. That shit is around, and so easy to get. And you can go for three hours and feel like a king, but it doesn’t work in the long run. Man, I’ve been there.”

In the wake of Betts’ death last week, Haynes spoke highly of his compadre’s musical talent. “Dickey played awesome straight traditional blues, but he also had this Django Reinhardt-on-acid side of him that was very unique. Most cats that can play blues as convincingly as Dickey cannot stretch out to that psychedelic thing like he could.”

Duane Allman’s daughter, 55-year-old Galadrielle Allman, spoke glowingly about how Betts and her father created magic together. “It’s so hard to respond to losses like this, to try to comprehend that we all just keep losing the originals, the creators, the artists who wrote the book,” she said. “My father could not have reached the heights he reached without Dickey beside him. They raised one another up and created a sound together that changed music. We are so lucky that, although everything else eventually goes, the music stays.”

R.I.P., Dickey. I’m cranking up your music a lot these days…

****************************

The playlist below collects Allman Brothers Band songs written (and usually sung) by Betts, as well as songs he wrote for his solo LPs. Perhaps my favorite, “In Memory of Elizabeth Reed,” appears twice — in the incendiary electric version from 1971, and again in a live acoustic performance from 1995.