R.I.P. to a Motown tunesmith and a pop icon

The talented musicians, songwriters and entertainers who dominated the charts in the ’60s, ’70s and into the ’80s have been passing away with disconcerting regularity lately. Not surprisingly, some of them were important and influential to me, responsible for songs and/or albums that rank high among my musical preferences. Others, while wildly popular among many listeners, were never really my cup of tea. Such is the case with two notable deaths this week, both of whom I feel are worthy of a detailed look back.

***************************

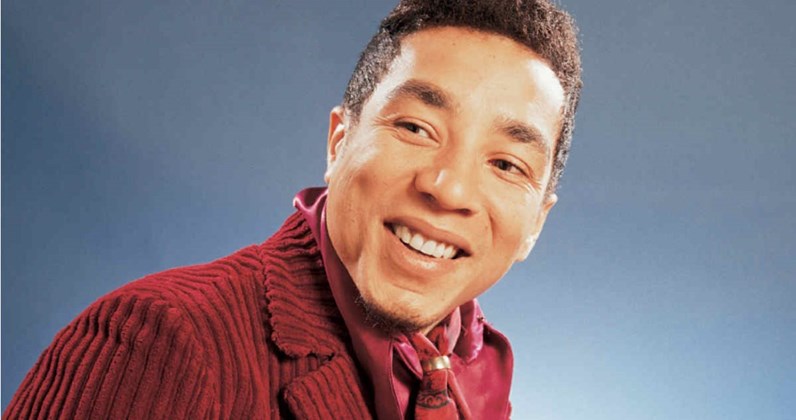

Because they work their magic behind the scenes instead of on stage, songwriters are often not widely known by name. That’s probably the case with Lamont Dozier, who died August 8th at age 81.

Dozier is partly responsible for many of the biggest hits to come from the legendary R&B artists at Motown Records in the 1960s. He teamed up with songwriting brothers Brian and Eddie Holland while they were all in their mid-20s and became Motown’s most successful songwriting team. Holland-Dozier-Holland, as they were known, composed an astounding TEN #1 singles for The Supremes between 1964 and 1967: “Where Did Our Love Go,” “Baby Love,” “Come See About Me,” “Stop! In the Name of Love,” “Back In My Arms Again,” “I Hear a Symphony,” “You Can’t Hurry Love,” “You Keep Me Hanging On,” “Love Is Here and Now You’re Gone” and “The Happening.”

As if that wasn’t remarkable enough, the trio also wrote the bulk of the hits registered by The Four Tops: “Baby I Need Your Loving,” “I Can’t Help Myself (Sugar Pie, Honey Bunch),” “It’s the Same Old Song,” “Reach Out I’ll Be There,” “Standing in the Shadows of Love” and “Bernadette.”

Hang on, I’m not done. Dozier and Company also wrote “How Sweet It Is (To Be Loved By You)” for Marvin Gaye (later a hit for James Taylor) as well as “Baby Don’t You Do It” (later covered as “Don’t Do It” by The Band), plus “You’re a Wonderful One” and “Can I Get a Witness.”

More? You bet: “Heat Wave,” “Nowhere to Run” and “Jimmy Mack” for Martha and The Vandellas; “This Old Heart of Mine” for The Isley Brothers; and “I’m a Road Runner” for Jr. Walker and The All-Stars.

These were just the biggest hits out of an enviable catalog that included many dozens of lesser singles for these and other acts. Talk about prolific!

“Brian and Eddie and I, we had a special kind of chemistry,” Dozier said for a 2003 Rolling Stone article. “It was like being at the carnival and hitting that bell. Bam! Number One! Bam! Number One! Bam! Number One! When we weren’t doing that with The Supremes, we were over here with the Four Tops. Bam! It was just surreal.”

As too often happens in the music business, Holland-Dozier-Holland got involved in an ugly, lengthy contract dispute with Motown mogul Berry Gordy in 1967 over profit-sharing and royalties, which wasn’t settled for more than a decade. The trio went out on their own label, but without Motown’s promotional muscle, they weren’t able to sustain as much commercial success. Still, a few of H-D-H’s songs climbed the charts with other artists, most notable Freda Payne’s #1 smash “Band of Gold” and Chairman of the Board’s #3 hit “Give Me Just a Little More Time.”

Dozier, born in Detroit in 1941, had begun his career as a singer with local doo-wop groups like The Romeos and The Voicemasters, so it wasn’t out of his wheelhouse to return to recording his own songs in 1972. He enjoyed some success on the R&B charts and had a #15 pop hit with 1974’s “Trying to Hold On To My Woman.”

He enjoyed a resurgence as a songwriter in the ’80s when his song “Invisible” was a #21 UK hit and a #31 US hit for singer Alison Moyet. Then he teamed up with the ubiquitous Phil Collins to write “Two Hearts,” a #1 smash from the 1988 British film “Buster.” It won a Golden Globe for Best Original Song from a film, and was nominated for an Oscar and a Grammy as well. From that “Buster” soundtrack LP, Dozier also wrote “Loco in Acapulco” for The Four Tops.

Holland-Dozier-Holland were inducted in the Songwriters Hall of Fame in 1988 and the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1990.

In a 2019 interview, Dozier was humble in discussing his legacy. “Everything I wrote or co-wrote, I give credit to God, the master muse,” he said. “I thank him for letting me put my name on his music. That’s how I look at it. I don’t read music, and I can’t write it out either. I did it all by ear and feeling when I sat down at the piano. I’m stunned that I still hear all those songs over and over. It still hasn’t let up. It’s amazing. I thought some of it wouldn’t last a day. But it’s been here and all over the world for 60 years, and that’s a great feeling.”

****************************

For more than 50 years, Olivia Newton-John — wholesome songstress, iconic actress, sexy pop star, committed activist — has been in the public eye, and her worldwide legion of admirers shed a collective tear August 8 when she died at age 73, succumbing to a long battle with cancer.

Full confession: I’ve never been much of a fan of Newton-John’s music. I found her stuff to be way too cloying and middle-of-the-road for my rock and roll tastes, although she did adopt a more aggressive, uptempo approach for a while. To be fair, I haven’t really been a part of her demographic, so my opinion matters not at all to her millions of fans. I can say that I have enormous respect for her, both as an entertainer who gave her audience what they wanted, and as a strong woman of integrity who showed uncommon dedication to important health and environmental causes. By all accounts, she was a kind-hearted soul who embraced life.

She is most widely known as the goody-goody exchange student Sandy in the 1978 film version of the Broadway musical “Grease,” who radically transforms herself into a sexy vixen in order to win the heart of Danny, her erstwhile love interest played by John Travolta.

“My dearest Olivia, you made all of our lives so much better,” said Travolta this week in an Instagram post. “Your impact was incredible. I love you so much. We will see you down the road and we will all be together again. Yours from the first moment I saw you, and forever! Your Danny, your John!”

Born in Cambridge, England, Newton-John was just 6 when her family moved to Melbourne, Australia. She was 14 when she formed her first group, Sol Four, with three girls from school. Program directors at local Australian TV stations, enamored by her voice and charisma, began featuring her in solo performances under the name “Lovely Livvy.” At 18, she came in first in a talent contest and won a trip to Britain, where she recorded her first single, “’Til You Say You’ll Be Mine” (although it failed to chart).

Her first chart appearance came in 1971 with a cover of Bob Dylan’s “If Not For You,” which reached #7 in the UK, #25 on the US pop chart and her first #1 on the US “adult contemporary” (read: easy listening) chart. This kicked off a run of five pristine, quasi-country singles that established her presence on Top 40 radio through the mid-’70s: “I Will Be There,” “If You Love Me (Let Me Know),” “I Honestly Love You,” “Have You Never Been Mellow” and “Please Mr. Please.” This was all pretty featherweight stuff, a Record of the Year Grammy notwithstanding.

That all changed in 1978 when Newton-John was cast in “Grease.” Critics couldn’t ignore the fact that she not only turned in a winning acting performance but also gave the mega-platinum soundtrack album its biggest hits: “Summer Nights,” “Hopelessly Devoted to You” and especially “You’re the One That I Want,” her duet with Travolta that served as the film’s finale after she’d morphed into the tough chick. That new image — big hair, skintight black pants, off-the-shoulder black top, red stiletto heels, vamped-up makeup — was the one that adorned many a teenage bedroom wall.

Applying the evolution of her “Grease” character to her singing career, Newton-John titled her next album “Totally Hot,” complete with an album cover clad in shoulder-to-toe leather. The singles “A Little More love” and “Deeper Than the Night,” which peaked at #3 and #11 respectively, offered more aggressive rock flavorings than in the past, and her fan base went along for the ride.

In 1980, her next film, the musical fantasy “Xanadu,” was a box-office disaster (although it did great business when revived on Broadway years later). The soundtrack album, though, was another big success, thanks to the #1 single “Magic” and her collaboration with Electric Light Orchestra on the title track.

Her savvy management should get credit for her next move, which was to position her as a sort of exercise fitness queen in the Jane Fonda Aerobics mold on the cover of her 1981 LP “Physical.” She gave the music video industry and MTV a shot in the arm with a suggestive video often depicting buff hardbodies in Speedos working out around Newton-John’s instructor as she sang the double entendre lyrics.

Hank Stuever, in a commentary in The Washington Post this week, wrote: “You can hear ‘Physical’ a hundred times, maybe a thousand, before you really hear what it’s about, and it’s not exercise. It’s a woman taking control of seduction, claiming for herself the tactics usually deployed by men: the flirtation, the dinner, the movie, the horny insistence. ‘There’s nothing left to talk about, unless it’s horizontally… /I’ve been patient, I’ve been good, tried to keep my hands on the table, /It’s gettin’ hard, this holdin’ back, you know what I mean… /You gotta know that you’re bringin’ out the animal in me, /Let’s get physical, physical…‘ Although Newton-John would not survive a coming onslaught of the far more suggestive pop hits of Prince and Madonna and beyond, she showed us a door to a kind of forbidden zone, if you chose to go through it, and naturally, we did.”

The song, of course, went through the roof, setting records by remaining in the #1 slot for a ridiculous 10 weeks in 1981. An international tour, a greatest hits package with a hot new single (“Heart Attack”) and an HBO special all followed in rapid succession. It seemed the world couldn’t get enough of The New Olivia. Reuniting her with Travolta in the 1983 film “Two Of a Kind” proved to be a misfire, although the single “Twist of Fate” was yet another Top Five single.

By 1985, she was a wife and a mom, and consequently put her career on hiatus for a while. When she re-emerged in 1989 with “Warm and Tender,” an album of lullabies for parents and their children, few people bought it, with fans deciding they preferred the new pop sensations like Debbie Gibson and Tiffany.

At age 44, she was diagnosed with breast cancer, and her life took on a whole new mission. She threw herself headlong into advocacy work for cancer research and self-examination, which augmented the efforts she had already been making on behalf of other health and environmental concerns. She established the Olivia Newton-John Foundation Fund that remains active to this day.

It gave me pause this week to see a quote attributed to her from a 2019 interview with Rolling Stone regarding her audience-friendly approach to music: “It annoys me when people think because it’s commercial, it’s bad,” she said. “I think it’s completely the opposite. If people like it, that’s what it’s supposed to be.”

Fair enough. Rest in peace, Olivia.

******************************

I have compiled two Spotify lists below, one featuring the songs written by Lamont Dozier, and another that highlights Olivia Newton-John’s biggest hits.