Talk about a pair of books that are right in my wheelhouse! In 2017, author Marc Myers came up with “Anatomy of a Song: The Oral History of 45 Iconic Hits That Changed Rock, R&B and Pop,” in which he interviewed the artists and producers involved in creating some of the more seismic songs of the rock era. He doubled down in 2022 with “Anatomy of 55 More Songs,” which cumulatively gave us the “how they came to be” stories behind an even 100 records that broke barriers and forged new directions in the early development of rock, pop and soul music.

Some songs have been around for so long and have been so ingrained in our minds that we may take for granted how ground breaking they were when they were released. In many cases, we’ve been unaware what went into writing and recording them. Myers has done an admirable job of shining a light on “the discipline, poetry, musicianship, studio techniques and accidents that helped turn these songs into meaningful generational hits that still endure today,” as he put it in his introduction.

For the purposes of this blog entry, I have selected eight songs from the Myers books that serve to represent the first four decades of the rock era: Two songs each from the 1950s, 1960s, 1970s and 1980s. These are, for the most part, songs I truly love and respect as game changers in rock’s evolution. My takes are admittedly not as detailed as those published in the books, but they include key comments from the principals involved as well as a few opinions of my own.

****************************

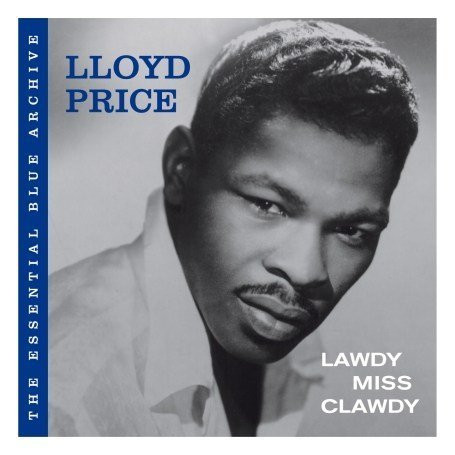

“Lawdy Miss Clawdy,” Lloyd Price, 1952

What was the first rock and roll record? A few dozen songs have laid claim to that designation, from Fats Domino’s “The Fat Man” to Ike Turner’s “Rocket 88,” but surely Lloyd Price’s 1952 classic “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” is in the running. Price was a self-taught piano player and singer from New Orleans who would play on a beat-up old piano in his mother’s sandwich shop, hoping to someday write and record a song that could be played on her jukebox. “I remember a black radio announcer who often said, ”Lawdy, Miss Clawdy, eat your mother’s homemade pies and drink Maxwell House coffee,'” Price said. “I loved that phrase and began fooling around on the piano with that line. One day a customer asked me to play it all the way through. Turned out it was Dave Bartholomew, one of the most important R&B musicians and producers in New Orleans.” Said Bartholomew, “The feeling in his voice caught me. Lloyd sang it with such emotion and intensity.” The lyrics bemoaned the fact that although “Miss Clawdy” excited him, she wasn’t interested in him. Bartholomew was impressed enough with Price and his song that he brought in his own band to a local studio, worked up an arrangement, and had Price sing it “with his soulful authenticity,” and within a few weeks, it was on the radio, peaking at #1 on the R&B charts for seven weeks. Domino recorded it himself 15 years later, as did Joe Cocker in 1969, and Paul McCartney on an album of oldies in 1988.

“Shout,” The Isley Brothers, 1959

In the late ’50s, singer Jackie Wilson made a huge impact on R&B and early rock ‘n roll, and other acts like The Isley Brothers paid close attention. In particular, Ronald Isley was so taken by Wilson’s “Lonely Teardrops” that he and his brothers began singing it to close out their shows. “Jackie would sing ‘say you will’ and his backup singers would respond in kind, and Jackie would then ad-lib, ‘say it right now, yeah baby, come on, come on,'” remembered Isley, “so when we did it, I continued that ad-libbing, things like ‘you know you make me want to shout’ and ‘kick my heels up’ and ‘don’t forget to say you will.’ Audiences just went wild over the participatory call-and-response, which was straight out of gospel.” The Isleys were urged to record the “Shout” ad-lib part as a separate song, without “Lonely Teardrops” before it, and they invited friends to the studio to give the record a party atmosphere. “Shout” was released in 1959 but managed only #47 on the pop chart. In 1962, the New-Jersey-based Joey Dee and The Starlighters took their less soulful version to #6 on the charts. In 1978, when the producers of “National Lampoon’s Animal House” began selecting a soundtrack for the film (set in 1962), they decided “Shout” would be the perfect vehicle for Otis Day and The Knights to play at the frat house toga party. The movie was a huge success, and that version of “Shout” took on a life of its own, to the point where virtually every wedding reception you’ve attended since has whipped up the crowd on the dance floor with it.

“You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feeling,” The Righteous Brothers, 1964

Barry Mann and Cynthia Weil, the husband-and-wife songwriting team operating out of New York City’s famous Brill Building in the ’50s and ’60s, were asked by legendary L.A.-based producer Phil Spector to write songs for The Righteous Brothers, who had struggled for two years to chart a song in the Top 40. Spector heard the potential in their voices — Bobby Hatfield’s tenor and Bill Medley’s baritone — and knew they’d be big if only they had the right song and his production chops. “We loved the yearning and slow buildup of The Four Tops’ ‘Baby I Need Your Lovin’,’ which had just been released,” recalled Weil, “and we wanted to write something in that vein.” Mann came up with the great opening line, “You never close your eyes anymore when I kiss your lips,” and the story of heartbreak flowed from there through two verses and the chorus, but they turned to Spector for help with the bridge, which turned out to be the same chord progression as in “Hang On Sloopy.” He had Medley sing the verses alone, doing numerous takes on top of Spector’s trademark “wall of sound” instrumental layering. “I’d been through a breakup, so the aching emotion you hear was real,” said Medley. For the finished record, Spector chose to slow the tempo, which Mann objected to at first, but it made for a more dramatic, longer single, and it worked magnificently, reaching #1 in February 1965.

“Whole Lotta Love,” Led Zeppelin, 1969

“I came up with the opening guitar riff back in 1968 and I knew it was strong enough to drive the entire song,” recalls Jimmy Page. “It felt addictive, like this forbidden thing.” He had a master plan for it, which is why he didn’t rush to record it for Led Zeppelin’s quickly recorded debut LP in late ’68, instead working on it over the next nine months and saving it as the opening track for the band’s second album. As a former “studio brat” and session musician, Page loved to experiment with recording techniques, using different mikes to capture the drum sound he wanted from John Bonham. He also employed a new electronic instrument called a theremin during the free-form middle section, and had Robert Plant record his vocals in a separate booth to better isolate his voice. When Page later mixed the track with engineer Eddie Kramer, they worked with older equipment with rotary dials instead of sliding faders, which allowed them to send the guitar solo and vocals back and forth from one channel to the other, a radical tactic at the time. Plant, meanwhile, ruminated on what lyrics to sing and decided to lift lines from Muddy Waters’ 1962 blues tune “You Need Love,” which generated a lawsuit years later requiring back royalties and co-writing credit for Waters. Said Plant, “Page’s riff was Page’s riff. It was there before anything else. I just nicked the words, now happily paid for. We figured it was far enough away in time … but hey, you only get caught when you’re successful (“Whole Lotta Love” reached #4 in the US). That’s the game.”

“Rock the Boat,” Hues Corporation, 1974

If you’re not a fan of disco music, I guess you can blame it on The Hues Corporation, who came up with one of the first examples of the genre in 1973. Songwriter Wally Holmes had formed a soul/funk group he wanted to name Children of Howard Hughes but was advised against it, so he altered it to The Hues Corporation instead. “I would often write in terms of ‘do re mi’ and so on,” said Holmes. “Those kinds of things like ‘Row, Row, Row Your Boat’ tend to stick around for a long time, and ‘Rock The Boat’ came out of that, but it was written on the beat, so it was pretty stiff.” Producer John Florez agreed: “The first version was a dog that had nothing going on. I brought in arranger Tom Sellers, who had just come back from the Caribbean where he heard a dance beat that had an upbeat at the end of each measure. Then I brought in Joe Sample, Wilton Felder and Larry Carlton from the Jazz Crusaders and Jim Gordon on drums, and they laid down a groove with a backward beat, like a rumba.” The Hues Corporation vocalists laid their parts in on top, and with horns and strings added for the crowning touch, “Rock The Boat” had an irresistible dance-ability that DJs at New York underground clubs couldn’t resist. At RCA, they chose a different song as the group’s single, but word got out about how “Rock the Boat” was all the rage on dance floors. It was rush-released as a single, and by May 1974, it was #1 on pop charts. After that, many dozens of songs followed that mimicked the Sellers/Gordon beat and arrangement, and the disco era was born.

“Another Brick in the Wall (Part Two),” Pink Floyd, 1979

“I got criticized for writing an anti-education song,” said Roger Waters, “but it was never that. It was a protest song against the tyranny of stupidity and oppression, which I experienced at my high school in the ’50s. They were locked into the idea that young boys needed to be controlled with sarcasm and brute force to subjugate us to their will. I just wanted to encourage anyone who marches to a different drum to push back against those who try to control their minds, rather than to retreat behind emotional walls.” The concept behind “The Wall,” he said, was inspired by the barrier he felt had been erected between the artist and the audience at many of Pink Floyd’s concerts. He also wanted the music to graphically depict the alienation and isolation Waters had felt in his life. His father’s death at a young age became the first brick (Part One), while the stifling school experience (Part Two) was the second brick, and the character’s mental breakdown after his wife’s betrayal (Part Three) was the final brick. The Part Two track that became a #1 single for Pink Floyd in early 1980 was almost finished when engineer Nick Griffiths hit on the idea of recording children from a nearby high school adding their defiant voices on the chorus. When combined with a throbbing bass line, thumping drum beat, and David Gilmour’s sublime guitar solo, “Another Brick in the Wall” became something truly memorable.

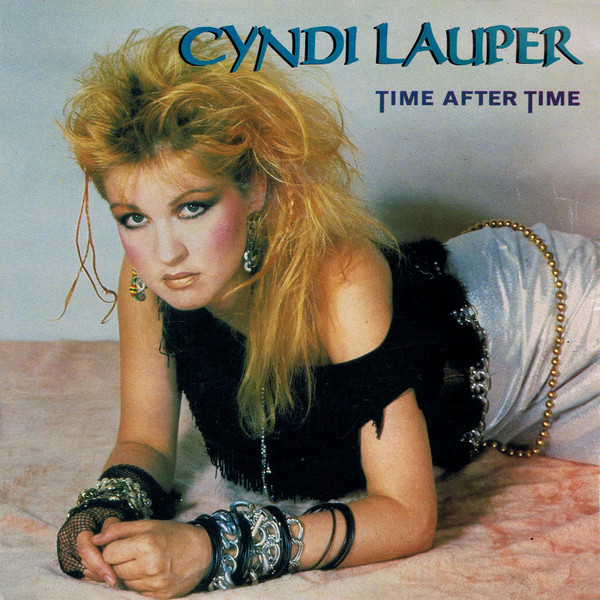

“Time After Time,” Cyndi Lauper, 1983/4

Keyboardist Rob Hyman collaborated with singer Cyndi Lauper on this stunning track as the final song to be recorded for her landmark debut album, “She’s So Unusual.” Said Lauper, “We knew ‘Girls Just Want to Have Fun’ would be the first single, a bouncy tribute to the female spirit. But I wanted to write a song with Rob that would be a deeper, more heartwrenching ballad.” Hyman had a repetitive piano melody based on four chords, and Lauper had seized on the phrase “time after time” as a possible title after seeing a TV Guide listing for the 1979 film of that name. Words came out about the constancy of having someone’s back –“If you fall, I will catch you, I will be waiting time after time” — and as the serious lyrics took shape, they decided to reduce the tempo. “Even though we slowed down the music, the chorus retained that clipped, calypso-type melody, which worked perfectly,” said Hyman. Lauper’s song became a paean to female individualism and independence at just the right time, and it ended up at #1. An instrumental rendition of “Time After Time” was even recorded by legendary jazz great Miles Davis the following year.

“Nick of Time,” Bonnie Raitt, 1989

Writing songs from the heart that are commercially appealing is a rare gift, and Bonnie Raitt had struggled to come up with the right formula for years. By the mid-1980s, she took stock of her excessive partying and had what amounted to a spiritual awakening, giving her a renewed sense of optimism about her career. “I retreated to Mendocino to write some new music honoring how grateful I felt to have made it through tougher times,” she said. “I began thinking about the most poignant aspects of my life as I approached 40, and I tried to capture the essence of what my friends were going through as well. I realized this whole idea of time being more precious as we age would be what I wanted to write about.” The main theme — “I found love, baby, love in the nick of time” — was more about a universal love than romantic love but could be interpreted either way. Because the lyrics were so heartfelt, she felt the song needed a mid-tempo beat to deliver the message in a lighter, more pleasing way. “My demo of it was recorded with a drum machine that had pre-set synthesized grooves that were unintentionally hilarious to me,” Raitt said, but once she huddled with the great producer Don Was, he understood the soulful inspiration she was aiming for. He brought in drummer Ricky Fatter, “who knew how to translate the basic elements I had written to an updated organic feel.” The final result struck a chord and the “Nick of Time” LP reached #1 in early 1990, rejuvenating Raitt’s career.

*************************