Baby, it’s time to close that door

If you’re an ardent fan of blues music, you’re well aware of John Mayall. If you like the blues but don’t know much about its best practitioners, it’s important for you to know more about the pivotal role Mayall played in keeping the genre alive and popular through the many decades of his long career.

Mayall, who died this week at the ripe old age of 90, did nearly as much for the proliferation of blues music as did the early pioneers who first wrote and played the blues back in the ’20s, ’30s and ’40s in the rural American South.

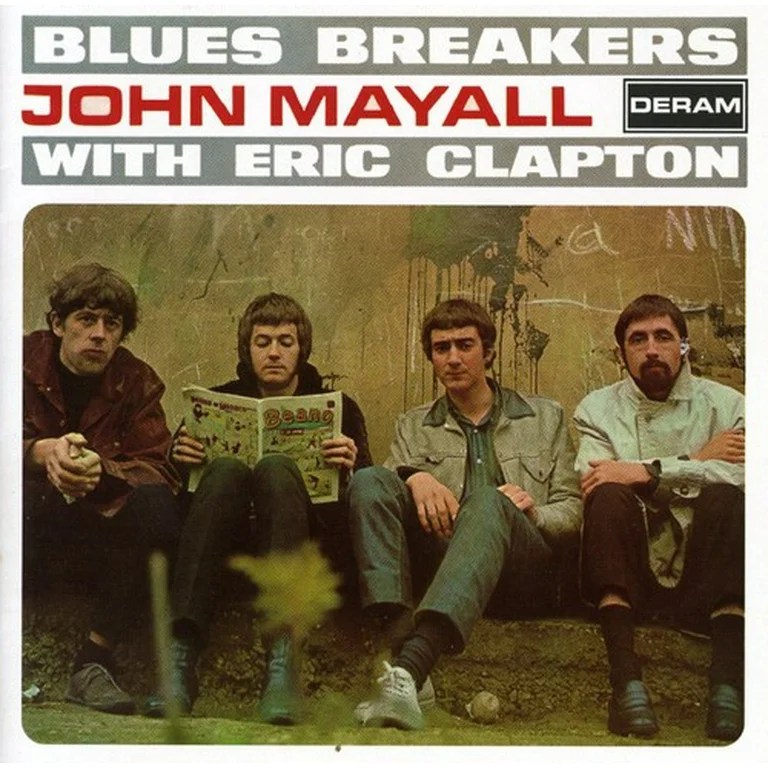

He had a well-earned reputation as a mentor and talent spotter of some of the more iconic names in British rock. Between 1965 and 2019, nearly a hundred different musicians have recorded with Mayall on more than 70 albums he released as a solo artist or under the name of his erstwhile band brand, The Bluesbreakers. Alumni include guitarist luminaries like Eric Clapton, Mick Taylor, Peter Green, Harvey Mandel, Rick Vito and Coco Montoya; drummers Mick Fleetwood, Aynsley Dunbar and Jon Hiseman; bassists John McVie, Jack Bruce, Larry Taylor and Andy Fraser; and sax greats Ernie Watts and James Holloway.

My introduction to Mayall came in 1969 when a friend turned me on to “John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers With Eric Clapton,” a 1966 album of extraordinary blues tracks brimming with instrumental and vocal prowess from Clapton and Mayall. At 14, I had already become a huge fan of Clapton through his incendiary work with Cream, but here was where I marveled at the talent he showed in his formative years as both a soloist and accompanist to Mayall on original songs (“Little Girl,” “Double Crossing Time,” “Have You Heard”) and classic covers (“All Your Love,” “Hideaway,” “Ramblin On My Mind”).

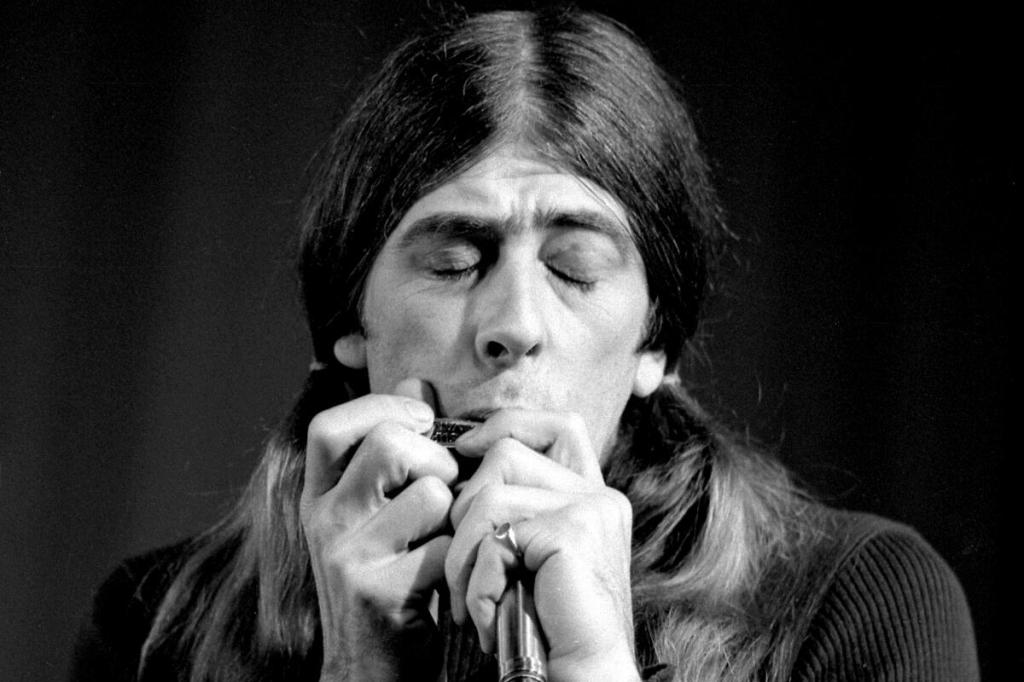

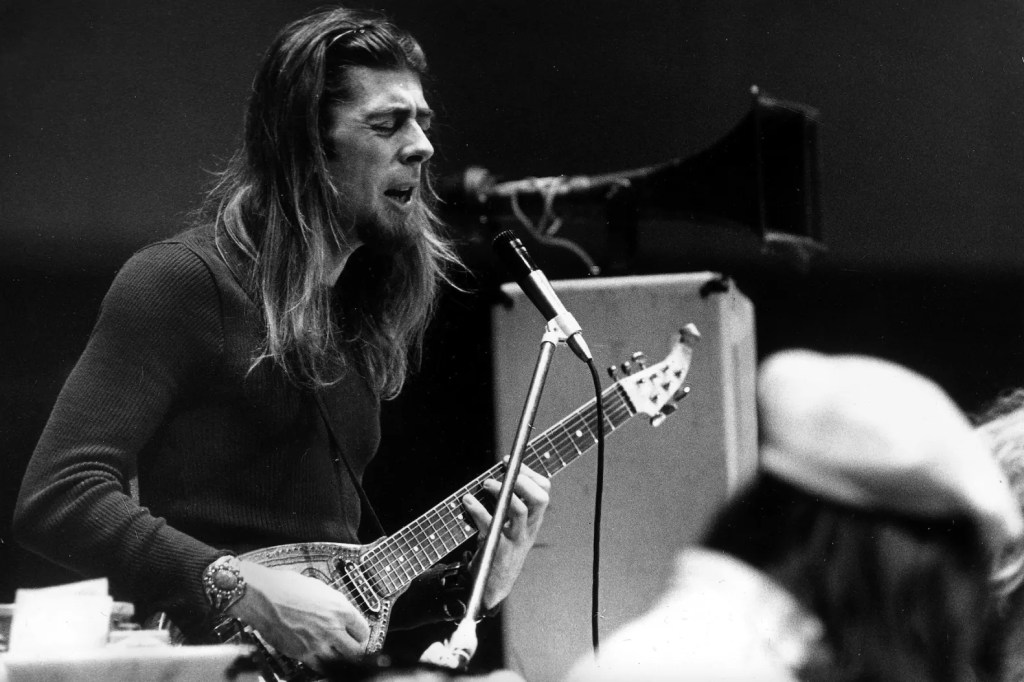

Mayall was a Brit from the Manchester area who was inspired by the Chicago and Mississippi blues records his father collected in the 1950s, rapidly becoming obsessed with the structure, emotion and appeal of blues music. Mayall developed a distinctive songwriting style that was both heavily indebted to an American art form and somehow still uniquely British. Mayall played piano, harmonica and guitar, and sang the blues with uncanny authenticity, sparking widespread interest in the blues among British musicians and listeners. They in turn triggered a ’60s blues revival in the US, as listeners who had been unfamiliar with the likes of homegrown blues talents like Freddie King, Otis Rush and Robert Johnson were snatching up albums by British blues-rock bands like the early Rolling Stones, The Animals and The Yardbirds.

Rather than limiting himself to traditional blues themes like unfaithful women or bad luck, Mayall distinguished himself by writing about the world around him. On “Nature’s Disappearing,” from 1970, he tackled pollution; on “Plan Your Revolution,” another track from that year, he sang about constructive political and social change. More recently, on “World Gone Crazy,” he explored the relationship between religious conflict and war. “Blues musicians ought to be singing songs about their own lives,” he said in 2014. “A lot of borrowing goes on in the blues, but it’s not just a matter of copying other people. You’ve got to think about representing your own life in the music. Blues has always been about that raw honesty with which it expresses our experiences in life, something which all comes together not only in the lyrics but the music as well.”

Though Mayall never approached the fame of some of his illustrious alumni — he was still performing in his late 80s, pounding out his version of Chicago blues — he wasn’t shy about expressing his disappointment about being eclipsed by his former mates. “I’ve never had a hit record, I never won a Grammy Award, and Rolling Stone has never done a piece about me,” he said in 2010. “I’m basically still an underground performer to most of the public. But I guess it’s just a part of my history. It really sums up the period of my life when I was in London. There was such a swift turnover of musicians at the time. All of them were just young guys who were just trying to find their feet, and I was able to help them along.”

Following Clapton’s departure in 1966, Peter Green became the focus for the next Bluesbreakers LP, “A Hard Road,” but he too left to form Fleetwood Mac, and Mick Taylor assumed guitar duties for “Crusade.” But by 1968, Mayall found himself drawn to America, specifically Los Angeles, where he bought a house in Laurel Canyon and ended up living in the area for the rest of his life. He cast aside the Bluebreakers moniker for a spell, instead releasing solo efforts like “Blues From Laurel Canyon” and the popular live LP “The Turning Point,” which went gold and put Mayall in the Top 40 of the US albums chart with its compelling harmonica workout, “Room to Move.”

Mayall continued to experiment, recording his next album, 1970’s “USA Union,” with a new drummer-less band that included ex-Mothers Of Invention violinist Don “Sugarcane” Harris, which became his highest-charting album in America, reaching number 22 in the Billboard 200. For his follow-up, a sprawling 1971 double LP called “Back to the Roots,” he surprised fans by reuniting with Clapton and Taylor; it was the first in a series of line-up changes during his career in America, which gave Mayall an air of unpredictability. “My record label – Polydor at the time – asked me for new albums every few months, it seemed,” he explained in his autobiography. “To achieve this, I needed to keep the music fresh, and that meant rebuilding my line-up from time to time.”

Over the next four decades, Mayall continued to explore his love for the blues in a variety of different contexts. After taking a funkier direction in the late 1970s, he reverted back to blues rock in the 1980s, then revived the Bluesbreakers with the vital 1988 LP “Chicago Line.” In the ’90s, he even reunited with old friends like blues virtuoso John Lee Hooker on the album “Padlock on the Blues,” released just a year before Hooker’s death.

Fleetwood, one of many British musicians who owe a musical debt to Mayall, recalled his early encounters with him. “When you went around to John Mayall’s house, it was a shrine to the blues,” Fleetwood said. “He’d sit you down, almost like a school teacher, and he’d bring out this vinyl.” In the wake of Mayall’s death this week, Fleetwood added, “He created a platform, a stage, for musicians — me being one of them — that mustn’t be forgotten. John’s legacy is that he has been true to his schooling as a blues player. He has never compromised that, and he has never pretended to be anything other than that. He has stuck to his guns, and he has placed his love of the blues above anything else.”

It seems unfair that Mayall isn’t in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and almost cruel that his long-overdue induction in the Musical Influences category isn’t coming until three months after his death when he’ll be so honored in October.

It was a difficult task, but I cobbled together a playlist of some of Mayall’s finest moments under the Bluesbreakers tent and on his own. He has so much great material in his catalog that I could’ve easily doubled the length of this list and not suffered any in quality.

R.I.P., Mr. Mayall. Do yourself a favor, dear readers, and dive into the sturdy blues recordings of this unquestioned titan of British blues.

***************************