The road is long, there are mountains in our way

I have this love-hate relationship with the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame.

When it was first proposed in 1985, I embraced the idea. If country music and other genres can honor their pioneers and heroes, why not rock music? Over the years since, I’ve visited the museum in Cleveland four or five times and have always enjoyed the experience. But I’ve sometimes taken issue with the worthiness of some of the people selected for induction, and I’ve been miffed about bonafide candidates who have been perennially ignored for far too long.

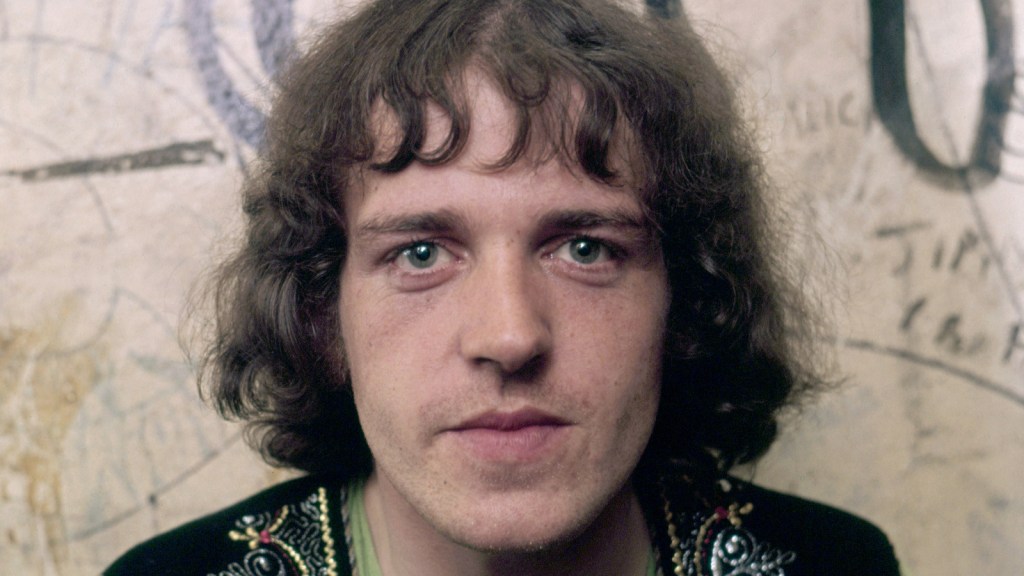

This year’s inductees were announced this week, and I’m pleased to see several vintage rockers finally get the nod: Joe Cocker, Bad Company, Warren Zevon, Nicky Hopkins. I’ll be writing about these artists in the coming weeks, beginning today with Joe Cocker.

*************************

In the late 1960s, when I was starting to buy albums and pay closer attention to rock music beyond just the Top 40 hit singles, I found that I didn’t like it at all when artists recorded cover versions of songs I already knew by other artists.

The first one I remember hearing, and hating, was Puerto Rican acoustic guitarist José Feliciano doing a re-interpretation of The Doors’ classic “Light My Fire.” (I eventually learned to like and admire it.) The other one that rubbed me the wrong way was Joe Cocker’s radical rearrangement of The Beatles’ “With a Little Help From My Friends.” I considered Beatles songs as sacred and couldn’t stomach anyone messing with them.

When the documentary film and triple album of the 1969 Woodstock Festival was released in the spring of 1970, I rather quickly had a change of heart about Cocker’s soulfully powerful version of what had been a singalong tune in its original form on the “Sgt. Pepper” album three years earlier. I happily conceded that Cocker had transformed the song into something entirely his own, something far more invigorating and vital. I was especially entranced by his visual performance of it in the movie — the frenetic stage presence, the flailing arm movements, the tie-dyed shirt and sweaty hair, and the stunning vocal delivery that alternated between plaintive and howling. I was sold.

I learned later that Paul McCartney and George Harrison had been mightily impressed by Cocker’s treatment of “With a Little Help From My Friends,” which had reached #1 on the UK charts upon its release in 1968. Said McCartney, “”it was just mind blowing, totally turning the song into a soul anthem, and I was forever grateful to him for doing that.” They took the unprecedented step of endorsing his use of Harrison’s ballad “Something” and McCartney’s rocker “She Came in Through the Bathroom Window” for his second album, “Joe Cocker!” even though The Beatles’ original versions hadn’t yet been released as part of “Abbey Road.”

“Joe Cocker!” zoomed up the charts in the US to #11, and it remains my favorite of Cocker’s 22-album catalog. In addition to the convincing Beatles covers, it also includes riveting renditions of Leon Russell’s “Delta Lady,” Bob Dylan’s “Dear Landlord,” Leonard Cohen’s “Bird on the Wire,” John Sebastian’s “Darling Be Home Soon” and the contagious “Hitchcock Railway.”

**************************

Born in 1944 in the north central British industrial community of Sheffield, Robert John “Joe” Cocker showed an early fascination with blues and skiffle (a British variant of folk and country), and considered Ray Charles and Lonnie Donegan his early influences. At 17, he took the stage name Vance Arnold and fronted a group called The Avengers, playing mostly American blues tunes by Muddy Waters and John Lee Hooker in Sheffield pubs, usually as a headliner but at least once as a warm-up act for the up-and-coming Rolling Stones.

His first attempt at fame came in 1964 when he recorded a bluesy cover of The Beatles’ “I’ll Cry Instead,” but it failed to chart, and Cocker dropped his stage name and formed Joe Cocker’s Blues Band, but that effort went nowhere as well. In 1966, he formed a partnership with guitarist/songwriter Chris Stainton and assembled an early lineup of what they called The Grease Band (inspired by a jazz musician who described a soul musician as “having a lot of grease”). They attracted the attention of producer Denny Cordell, who worked with The Moody Blues and Procol Harum, and Cordell encouraged Cocker and Stainton to relocate to London and recruit a better caliber of musicians for a new Grease Band lineup.

By 1968, Cocker had honed his act with a regular gig at the famed Marquee Club and won a contract with Regal Zonaphone in the UK and A&M Records in the US. The debut LP includes what has become the definitive version of “Feelin’ Alright,” the classic song Dave Mason wrote for Traffic, as well as a couple Dylan tunes and some competent Cocker/Stainton originals, and it reached a respectable #35 on US album charts, even though the “With a Little Help From My Friends” single stalled here at #68.

Critics loved Cocker’s grittily authentic voice. “He has one of the best rock voices in England, and he has no inhibitions about using it,” wrote Robert Christgau in The New York Times. “Cocker is the best of the male rock interpreters, as good in his way as Janis Joplin is in hers.”

After a grueling US tour in 1969 that included the appearance at Woodstock and at other major festivals, Cocker was exhausted and eager to take a break, but another set of dates had already been booked. He chose to dissolve the Grease Band (except for Stainton) and instead enlisted Leon Russell to assemble a crackerjack lineup of more than 20 musicians, including a 10-person “soul choir” and a three-man horn section, a confederation that became known as “Mad Dogs and Englishmen.” The group performed and partied hard for their 50-date tour in the spring of 1970, offering a spirited cross-section of rock and soul music.

The subsequent live album kept Cocker’s and Russell’s names in the limelight by reaching #2 on US charts in the fall of 1970. It spawned two Top Ten singles: a reworking of “The Letter,” the 1967 #1 hit by The Box Tops, and a rollicking take on the ’50s torch song “Cry Me a River.” Things looked good on paper, but under the surface, Cocker was coming apart at the seams, drinking heavily and suffering from severe depression. He withdrew from the L.A. music scene and returned to the care of his family back in Sheffield to recuperate. In his absence, A&M released the single “High Time We Went,” which peaked at #22 in the US in 1971.

By 1972, he was back on the road, and his next LP (also entitled “Joe Cocker,” later retited “Something to Say”) offered a combination of studio and live tracks, including the aforementioned “High Time We Went,” “Pardon Me Sir” and the minor hit “Woman to Woman” (all co-written by Cocker and Stainton) and a remake of Gregg Allman’s “Midnight Rider.” When Stainton decided to retire from touring and build his own recording studio to concentrate on production, Cocker relapsed into depression and began using harder drugs, with his alcoholism continuing to bedevil him.

And yet, in 1974 he was back on top with “I Can Stand a Little Rain,” a new album that showed a lighter side of the Cocker oeuvre, particularly the Billy Preston ballad, “You Are So Beautiful,” which peaked at #5 on US charts, his biggest success yet.

The pendulum swing of recovery and relapse was on display in 1976 when Cocker made a memorable appearance on the then-new “Saturday Night Live.” He struggled through a performance of “Feelin’ Alright” while John Belushi brazenly did his famous Joe Cocker imitation standing right next to him. Was Cocker being a good sport, or was he being ridiculed? He said years later that when he watched a tape of the show, he felt humiliated, and finally got serious about recovery, staying sober for the rest of his life.

Two positive developments occurred in 1982 that gave Cocker a renewed sense of pride. In a guest gig with the jazz group The Crusaders in 1981, he had recorded “I’m So Glad I’m Standing Here Today,” written expressly for him by Joe Sample and Will Jennings. Because it was nominated for a Grammy, he and the Crusaders were invited to perform it at the Grammys. Later that same year, Cocker teamed up with singer Jennifer Warnes to record “Up Where We Belong,” a song also co-written by Jennings, which was used as the theme song for the Richard Gere/Debra Winger film “An Officer and a Gentleman.” The song was an international #1 hit, won a Grammy for Best Pop Performance by a Duo , AND won the Best Song Oscar at the 1983 Academy Awards, where the two singers performed it together.

Said Warnes at the time, “I’d been a huge fan since my teens. I had a poster of him at Woodstock on my bedroom wall. I remember seeing him sing ‘I’m So Glad I’m Standing Here Today,’ and I was so moved, I was hollering out loud with joy, jumping up and down. After a difficult battle with drugs and alcohol, Joe was in total command once again. I knew at that moment that I would sing with Joe. Some people felt we were an unlikely pair to sing a duet, but I was thrilled, and I think it worked out pretty well!”

Cocker scored three more hits in the 1980s. He transformed Randy Newman’s sensually amusing song “You Can Leave Your Hat On,” which was used prominently in the film “9-1/2 Weeks” during Kim Basinger’s erotic striptease scene; he revitalized the early ’60s R&B classic “Unchain My Heart,” first made famous by his idol Ray Charles; and he reached #11 on US charts in 1989 with “When the Night Comes,” co-written by Bryan Adams and Jim Vallance.

Typically, I’m not much of a fan of live albums, but his 1990 release “Joe Cocker Live” is an impeccably performed and produced collection of Cocker’s best material from a 1989 show that reunited him with Stainton as well as The Memphis Horns.

Although he never made the US charts again after that, he released eight more LPs between 1994 and 2012, which did respectably in the UK and especially in Germany, where he has always had a huge fan base and performed there often. At the 25th anniversary of Woodstock in 1994, Cocker and Crosby, Stills and Nash were the only artists from the original festival to return, and they drew enthusiastic responses from the younger crowd.

Although Cocker wrote a handful of songs during his career, the vast majority of material he recorded was written by others. Some were unknown tunes that he made famous, while many were really good covers of tunes already made famous by others (“I Heard It Through The Grapevine,” “Summer in the City,” “Watching the River Flow,” “I Put a Spell on You,” to name just a few).

In 2007, he reflected on his continued popularity. “The actual singing experience, I really do still get a buzz out of it. I treasure the performances more, I think, because you’re kind of wondering how long you’re going to be doing it, so you tend to get into it. I think that’s what’s kept me going. There are other guys who have better voices, but I’ve worked hard to keep my live shows exciting. In many respects, that’s why the fans have hung in with me. I had my rough times in the ’70s, but I always try to get wrapped up in the tunes.”

He died in 2014 from lung cancer at age 70. Now, 11 years later, he’s belatedly joining the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. I wish he was still here to see it happen.

**************************