I’ve written about protest music before, but current events have compelled me to readdress the topic. The “golden age” of protest songs may have been in the late ’60s and early ’70s, but that doesn’t mean artists from more recent decades haven’t felt the need to compose and record tunes that speak strongly about hot-button issues, some of which — war and racial injustice, to name just two — are the same damn issues we sang about a half-century ago.

Now, in the past year but especially within the last couple of weeks, we are seeing outrageous scenes of a federal occupying force shooting (murdering) individuals in the streets of American cities. It’s beyond the pale, and it has awakened the conscience of millions of citizens, and not just in the cities where these things are happening. People are speaking out, marching, demanding justice, and it appears those responsible may actually face consequences. We shall see.

*************************

Art as a form of protest — in paintings, in music, in films, in photography — has been a particularly potent way of expressing our contempt for society’s ills. In particular, protest music has been around in this country ever since pre-Civil War slaves came up with songs bemoaning their brutal lot in life.

By the 1920s and ’30s, Delta blues musicians like Robert Johnson, Blind Willie McTell, Lightnin’ Hopkins, Sonny Boy Williamson and others wrote many dozens of blues songs that protested personal concerns: lack of money, lack of food, cheating spouses, broken down cars and other woes of bad breaks and hard times. In 1939, Albert King summed it all up this way: “Born under a bad sign, I been down since I began to crawl, if it wasn’t for bad luck, I wouldn’t have no luck at all.”

In the ’40s and 50s, folk music leaders like Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger began writing lyrics that exposed the broader hardships of the downtrodden and the unemployed. The songs espoused peace and humanity, and took issue with political leaders who seemed to have darker agendas. They posed philosophical questions (“Where have all the flowers gone?”) and described the horrors every soldier endures when war is waged (“Waist Deep in the Big Muddy”).

The Sixties famously brought marches, sit-ins, demonstrations and rallies, which occurred regularly in big cities across the nation and around the Free World. And the lyrics in songs by Bob Dylan and others seemed to play a crucial, even central role in the proceedings. Dylan’s “Blowin’ in the Wind” and “Masters of War,” Sam Cooke’s “A Change is Gonna Come,” Barry McGuire’s “Eve of Destruction” — these were meaningful messages that, for the first time, were infiltrating the realm of popular music. But even Dylan knew a song had only so much power to persuade: “This land is your land, and this land is my land, sure, but the world is run by people who never listen to music anyway.”

In a blog post ten years ago, I wrote about protest songs that had become commercially successful — songs like CSN&Y’s “Ohio,” Marvin Gaye’s “What’s Going On,” John Lennon’s “Give Peace a Chance,” Buffalo Springfield’s “For What It’s Worth,” Edwin Starr’s “War” and Creedence’s “Fortunate Son.” I also listed another few dozen songs that, while not mainstream hit singles, nonetheless became popular in the both the counterculture and the wider culture of the time.

In this post, I’m stepping outside the comfort zone of “Hack’s Back Pages” (music of the 1955-1990 years) to explore protest music from the most recent two decades. It seems entirely appropriate to do so as protestors and law enforcement have faced off against each other in the streets of America numerous times in the past several months.

Here are a baker’s dozen songs of protest released since 2000 that I’ve found worthy of discussion and your attention. If there are others that strike a fervent chord with you, I’m eager to hear about them.

**************************

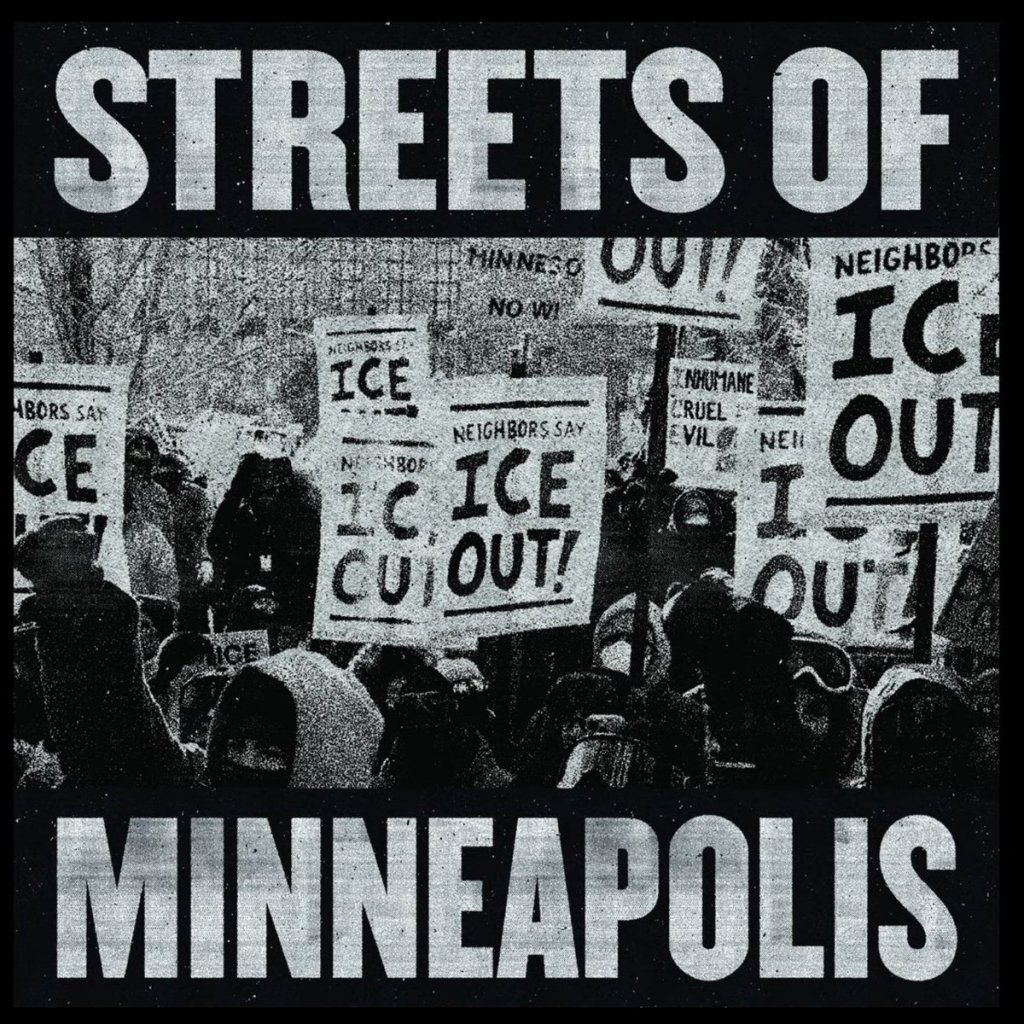

“Streets of Minneapolis,” Bruce Springsteen, 2026

Coincidentally, as I was preparing this blog entry over the past week, rock legend Springsteen wrote, recorded and released this searing protest song about violent events taking place in Minneapolis, Minnesota. With lyrics that specifically call out Trump and several of his “federal thugs” as well as the two innocent victims, the track has been described as “the 21st Century equivalent of Neil Young’s ‘Ohio’ following the 1970 Kent State shootings.” Clearly, “Streets of Minneapolis” comes from that same uneasy mix of sorrow and rage, and Springsteen offers lyrics that capture that pain and defiant response: “Citizens stood for justice, their voices ringing through the night, /And there were bloody footprints where mercy should have stood… Here in our home they killed and roamed in the winter of ’26, /We’ll remember the names of those who died on the streets of Minneapolis…”

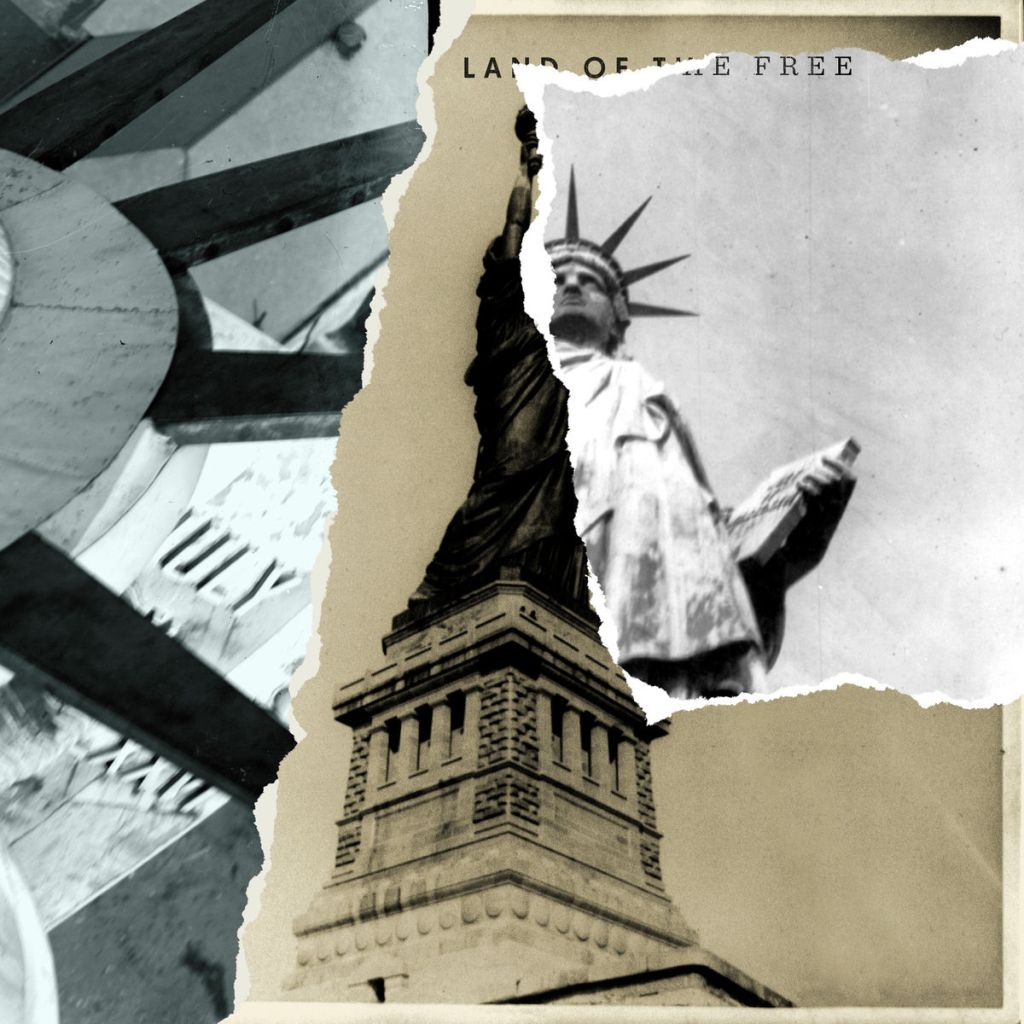

“Land of the Free,” The Killers, 2019

A Las Vegas-bred rock band since the early 2000s, The Killers have been led by singer-keyboardist Brandon Flowers, who has written or co-written nearly every song in their seven-album repertoire, all of which have reached the Top Ten on US charts (and #1 in the UK), resulting in nearly 30 million copies sold worldwide. Six years ago, Flowers wrote “Land of the Free,” a song that makes ironic use of the title to protest issues that still bedevil us in this country, specifically mentioning immigration, gun control and racism. In regards to the unfairness of systemic racism: “When I go out in my car, I don’t think twice, but if you’re the wrong color skin, you grow up looking over both your shoulders… Incarceration’s become big business, it’s harvest time out on the avenue in the land of the free…”

“Million Dollar Loan,” Death Cab For Cutie, 2016

Ben Gibbard, singer-songwriter for the popular alt-rock band Death Cab for Cutie, said he was outraged by then-candidate Trump saying during one of the 2016 presidential debates that he self-made his fortune “with just a small million-dollar loan” from his father. “He made it sound like anyone could get a million dollar loan,” Gibbard said, “which is just insane.” Gibbard poked a sharp stick at Trump’s silver-spoon upbringing: “He’s proud to say he built his fortune the old fashioned way, because to succeed, there’s only one thing you really need, a million dollar loan, nobody makes it on their own without a million dollar loan, you’ll reap what you’ve sown from a million dollar loan, call your father on the phone and get that million dollar loan…”

“World Wide Suicide,” Pearl Jam, 2006

Pearl Jam has a whole slew of overtly political songs in their catalog, and for their 2006 album “Pearl Jam,” several tracks dealt with the Iraq War and its aftermath, as well as the “War on Terror,” as it was referred to by the Bush Administration. I think “World Wide Suicide” is the best of the bunch. Singer Eddie Vedder has never been shy about challenging authority nor bemoaning the horrors of war in his lyrics: “It’s a shame to awake in a world of pain, what does it mean when a war has taken over, it’s the same everyday and the wave won’t break, tell you to pray while the devil’s on their shoulder, the whole world over, it’s a worldwide suicide….”

“I Give You Power,” Arcade Fire with Mavis Staples, 2017

Arcade Fire may be a Canadian band, but they still have the right to make their feelings known about political power in a free society, be it in the U.S. or elsewhere. Written by leader Win Butler with help from singer Mavis Staples in the spring of 2016 and released the day before Trump’s inauguration in January 2017, “I Give You Power” is a brilliantly concise reminder to those who win elections that they can lose their political power as easily as they win it: “I give you power, power, where do you think it comes from, who gives you power, where do you think it comes from, I give you power, I can take it all away, I can take it away, watch me take it away…”

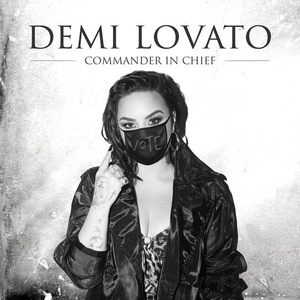

“Commander in Chief,” Demi Lovato, 2020

In the months leading up to the 2020 election, Lovato was incensed with the way she felt Trump mishandled the COVID pandemic and seemed to condone racial injustice and white supremacy. Perhaps naively, she sought a meeting with him to discuss these issues but instead chose to write a song about it, which became “Commander in Chief,” released in October of that year. Critics called it “the most potent, damning protest song of the Trump era.” The lyrics ask a series of questions that demanded answers, set to somber music that begins despairingly but swells to righteous indignation: “Won’t give up, stand our ground, we’ll be in the streets while you’re bunkering down… If I did the things you do, I couldn’t sleep, /Seriously, do you even know the truth? /We’re in a state of crisis, people are dying while you line your pockets deep…”

“Song for Sam Cooke (Here in America),” Dion with Paul Simon, 2020

Pop singer Dion DiMucci, famous for early rock hits like “The Wanderer” and “Runaround Sue,” re-emerged a few years back with Paul Simon for a powerful duet about the late Sam Cooke, one of the best soul/gospel singers of all time, who was gunned down in 1964 by a white motel owner. The lyrics deal with the racism of those times while reminding us that race relations are still tenuous in many parts of the country today: “I never thought about the color of your skin, I never worried ’bout the hotel I was in, here in America, here in America, but the places I could stay, they all made you walk away, you were the man who earned the glory and the fame, but cowards felt that they could call you any name, you were the star, standing in the light that won you nothing on a city street at night…”

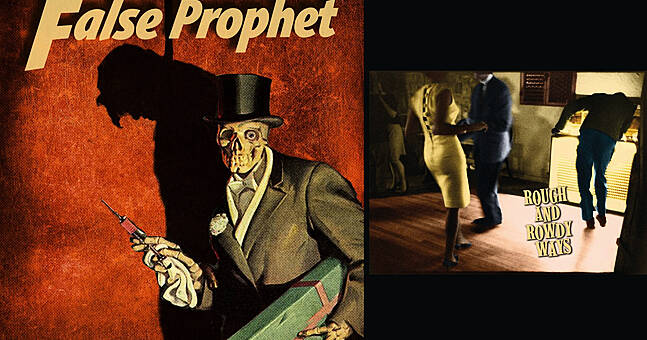

“False Prophet,” Bob Dylan, 2020

The man who offered up such iconic ’60s protest songs as “The Times They Are A-Changin’” and “Only a Pawn in Their Game” was still at it nearly 60 years later with 2020’s “Rough and Rowdy Ways,” a new album of thought-provoking tunes. In addition to a 17-minute epic about the Kennedy assassination called “Murder Most Foul,” Dylan wrote “False Prophet,” which commented on Trump’s first term: “Another day that don’t end, another ship goin’ out, another day of anger, bitterness, and doubt, I know how it happened, I saw it begin, I opened my heart to the world and the world came in…” Later, he makes reference to Trump and what might still be his fate, but that has, sadly, been wishful thinking so far: “Hello stranger, a long goodbye, you ruled the land, but so do I, you lost your mule, you got a poison brain, I’ll marry you to a ball and chain…”

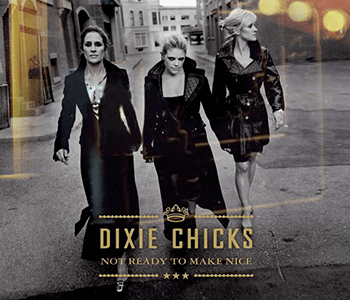

“Not Ready to Make Nice,” The Dixie Chicks, 2006

The Texas-based, three-woman country group, riding high in 2003 as one of country music’s most popular acts, came out against the Iraq War while performing in England, adding, “We’re ashamed that the President of the United States is from Texas.” The backlash from the group’s conservative fan base was fierce and instantaneous, and most country radio stations began boycotting their music. It took them off the charts for a few years before they returned with “Not Ready to Make Nice,” which reinforced their previous statements, not angrily but with a heartfelt rejoinder that defended their right to speak their minds: “How in the world can the words that I said send somebody so over the edge that they’d write me a letter, saying that I better shut up and sing or my life will be over? I’m not ready to make nice, I’m not ready to back down…”

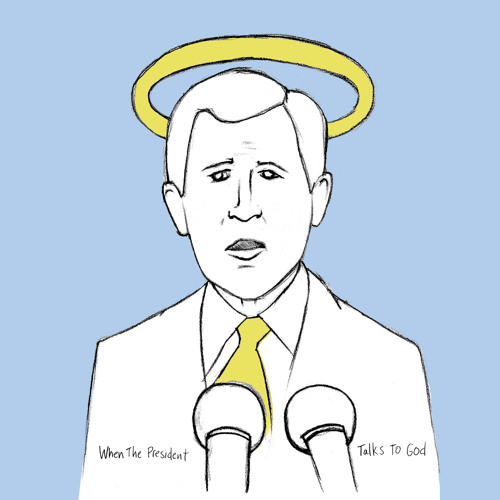

“When the President Talks to God,” Bright Eyes, 2005

Since the beginnings of the nation, presidents have mentioned God and the need for guidance, but none quite as arrogantly as George W. Bush, who claimed to have actual conversations with God. Conor Oberst, the singer-songwriter behind the indie rock band Bright Eyes, wrote this piece that took strong exception to Bush’s use of God to justify his policies and decisions. In early 2005, NBC surprisingly gave the green light to Bright Eyes performing the song on “The Tonight Show.” It was released as a free track on iTunes shortly after: “Does he fake that drawl or merely nod when the president talks to God? Does God suggest an oil hike when the president talks to God? Does what God says ever change his mind when the president talks to God? When he kneels next to the presidential bed, does he ever smell his own bullshit when the president talks to God?…”

“There’s a Tumor in The White House,” Dan Mangan, 2025

Mangan, a Canadian singer-songwriter whose career began in Vancouver in 2005 and earned him several Juno Awards in 2012, was motivated by recent belligerent remarks by the Trump administration against Canada write this . “Generally, in my songwriting, I’ve aimed for the timeless social criticisms — never too on the nose, never too specific,” he said. “But now we’ve got this bully in the highest seat using the lowest form of mudslinging and name-calling, and unfortunately, it just seems to keep working for him. I just wanted to call a spade a spade – bootlickers, chokeholders, chest-puffers… Is it ironic? I don’t know. Is it a joke? I worry that it isn’t.” Sample lyrics: “There’s a tumor in the White House, there’s a blowhard at the gate, /Chokeholders in the squad car, bootlickers on parade…”

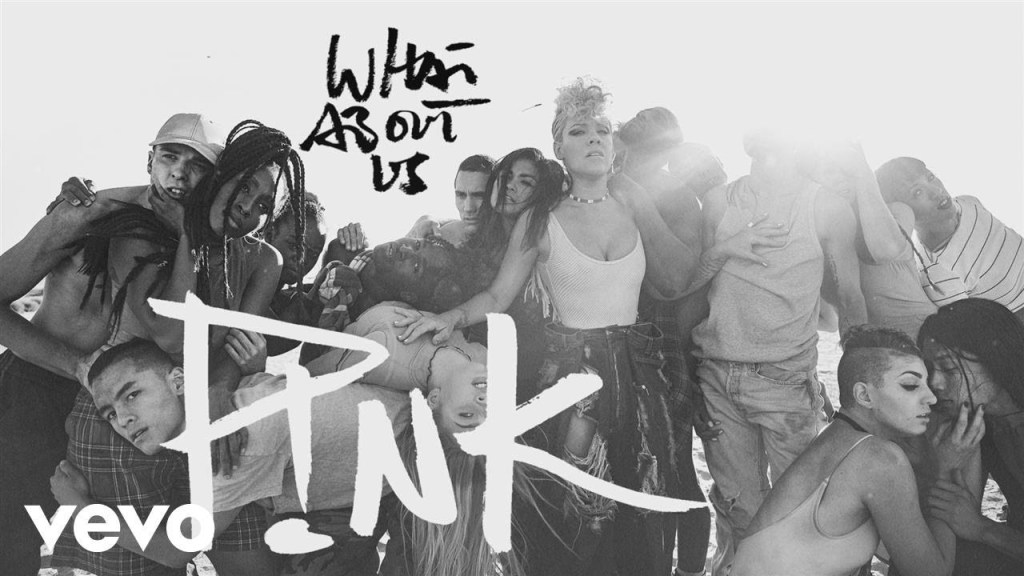

“What About Us,” Pink, 2017

Alecia Beth Moore, better known as the multi-talented singer-songwriter Pink, has enjoyed a spectacular solo career since her debut 20 years ago. Selling upwards of 90 million albums worldwide with multiple #1 albums and singles, she avoided being typecast as a mindless pop act by writing songs of real substance and using her gymnast-like dancing skills to reach new levels of artistry in her live performances. When she wrote “What About Us” for her 2017 album “Beautiful Trauma,” she kept it general enough so it could be interpreted to be about a failed relationship, but most believe it to be a political protest song about the Trump administration: “We are billions of beautiful hearts, and you sold us down the river too far, we were willing, we came when you called, but man, you fooled us, enough is enough… What about all the times you said you had the answers? What about all the plans that ended in disasters? What about love? What about trust? What about us?…”

“Hell You Talmbout,” Janelle Monae, 2015

Not so much a song as a chant with gospel overtones, this track (the title is a contraction for “What the hell are you talking about?”) is a powerful message piece that Monae wrote and recorded with a loose collective of musicians she called Wondaland. Originally, the verses painted vignettes of three black people who died at the hands of overzealous police, but as more such incidents began occurring, the lyrics evolved into a chanting of names of the victims, imploring listeners to “say their names!” David Byrne, late of Talking Heads, was so impressed by it that he concluded many of his concerts with his own rendition of it. A live recording of Byrne with a chorus and tribal drums is included in the Spotify list below.

*****************************

I’ve included two Spotify playlists. The first features the recent songs discussed above, while the other offers a handful of classic protest songs from the Sixties and Seventies.