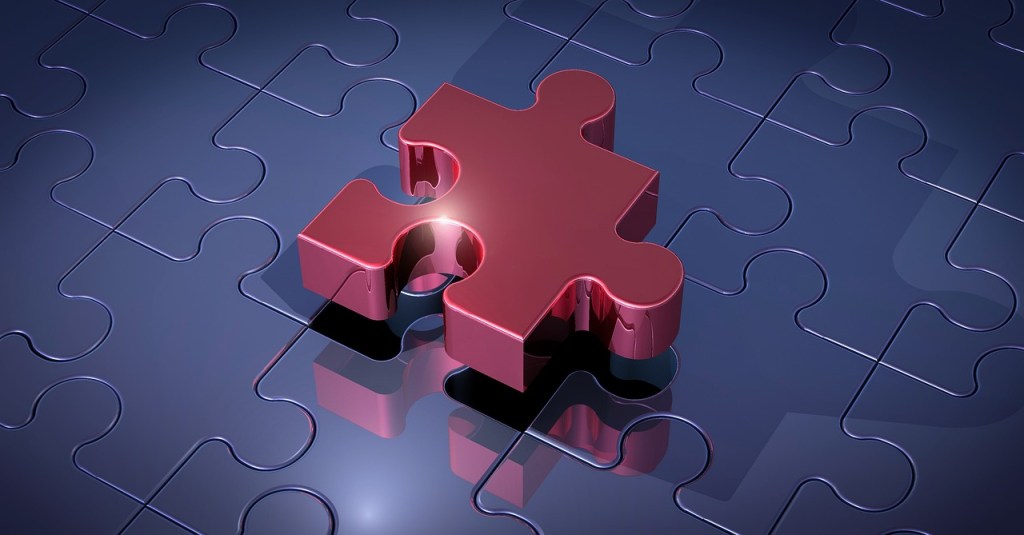

A small piece of the bigger picture

Because I’m always researching musical artists, albums, songs and lyrics, my social media feed often sends me things related to these topics. I saw something pretty cool the other day that I thought would make a great idea for a quiz on Hack’s Back Pages.

In the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, when we bought a new album, we held it in our hands and studied the album cover. The artful depictions were alternately fascinating, enigmatic, shocking, busy, sublime, even boring sometimes, but we looked at them so often, they became deeply ingrained images that still register today. Or do they?

What if you were to see only a small fraction of a classic album cover? Could you still recognize it?

I perused several dozen well-known album covers from the classic rock era, saved the images, then cropped way in so that only about 10% of the cover is visible. Below you’ll find 25 album covers you would likely recognize if you saw the entire images, but can you identify them from the small sections I’ve captured?

Study the partial images, jot down your guesses, and then scroll down to see how well you did, and learn some background on how the covers were created. There’s a Spotify playlist at the end to enjoy later.

*************************

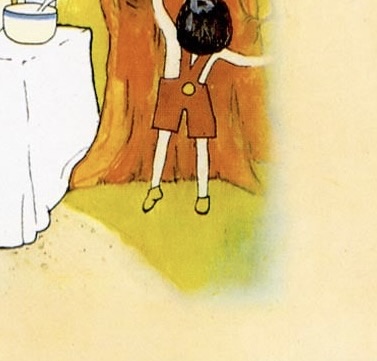

#1

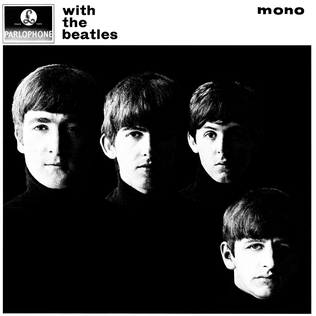

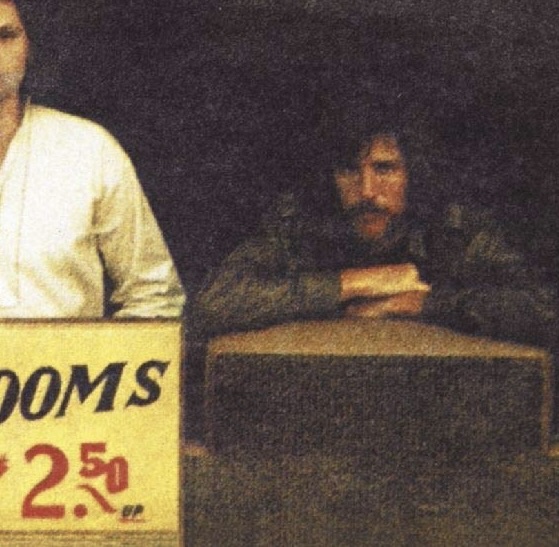

#2

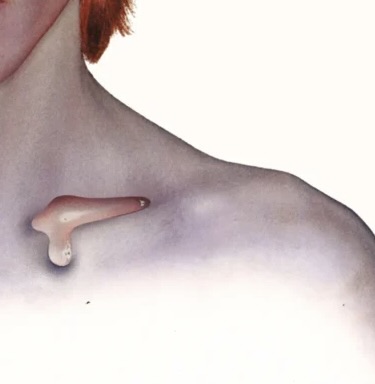

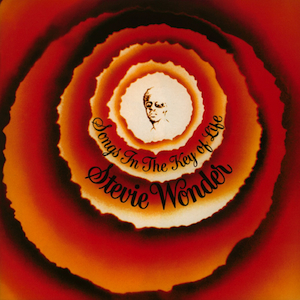

#3

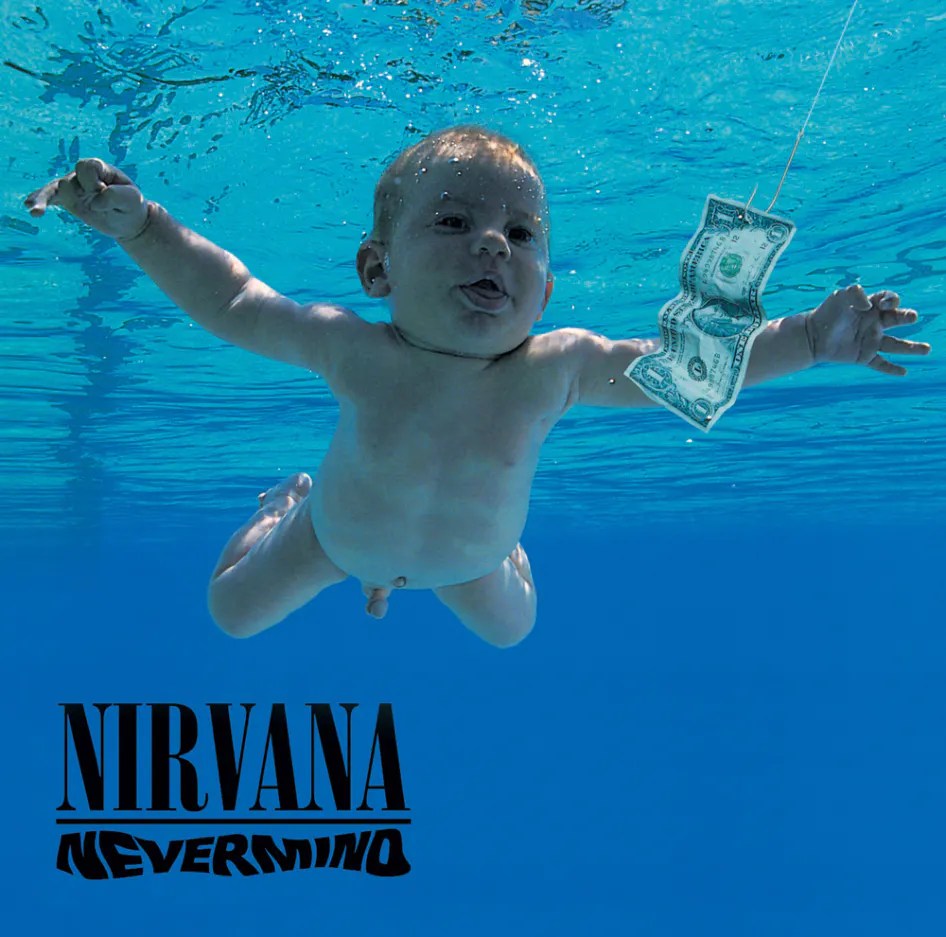

#4

#5

#6

#7

#8

#9

#10

#11

#12

#13

#14

#15

#16

#17

#18

#19

#20

#21

#22

#23

#24

#25

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

ANSWERS:

#1

This fanciful cover is the work of Ian Beck, a British illustrator and author of children’s books. He dabbled in album cover illustrations for a short while in the 1970s, turning in an amazing image for Elton John’s “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,” the 1973 double LP of 20 John/Taupin songs that pay tribute to the movie business.

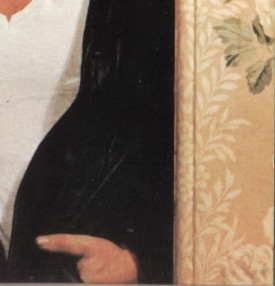

#2

Frank Stefanko, a photographer inspired by film noir movies and reality photographer Diane Arbus, developed a long-time relationship with Bruce Springsteen, conducting many photo shoots with him since the 1970s. He captured the stark image of the star in a small New Jersey house that graces the cover of 1978’s “Darkness on the Edge of Town.”

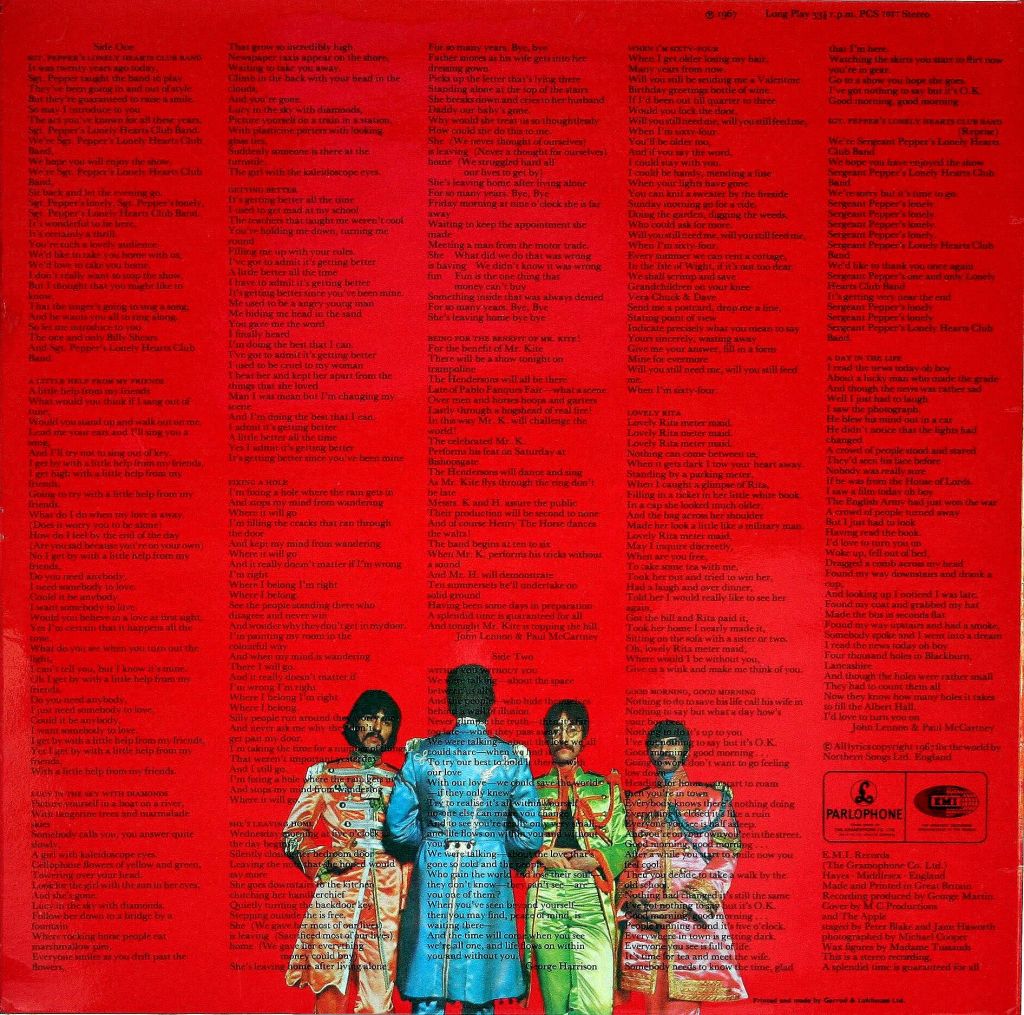

#3

The artwork for Stevie Wonder‘s landmark 1976 double album “Songs in the Key of Life” is credited vaguely to “Motown Graphics Department.” The story goes that it was designed as a double-edged metaphor — Wonder looking inward for personal visions and outward to the cosmos for divine inspiration.

#4

After watching a TV show on water births, Nirvana‘s Kurt Cobain wanted something similar for their second LP cover. Photographer Kirk Weddle shot photos of 4-month-old Spencer Elden, the son of a friend, at a neighborhood pool, using a dollar bill dangling on a fishhook to symbolize our lifelong pursuit of wealth. The cover of the 1991 album “Nevermind” is one of the decade’s most iconic.

#5

Pop artist Andy Warhol designed this famous image for The Rolling Stones‘ 1971 classic “Sticky Fingers.” Original pressings featured not only a working zipper, but a hidden second cover showing a pair of “tighty whities” and Warhol’s name stamped on each copy. It marked the first release on The Stones’ own record label after their Decca contract expired.

#6

Carlos Santana saw German/French painter Mati Klarwein’s dazzling 1961 work in a magazine one day and insisted that it be selected for use on the cover of Santana’s 1970 classic second LP “Abraxas.” Klarwein went on to contribute art for several other albums in the 1970s by the likes of Miles Davis, Herbie Hancock, Earth Wind & Fire and Gregg Allman.

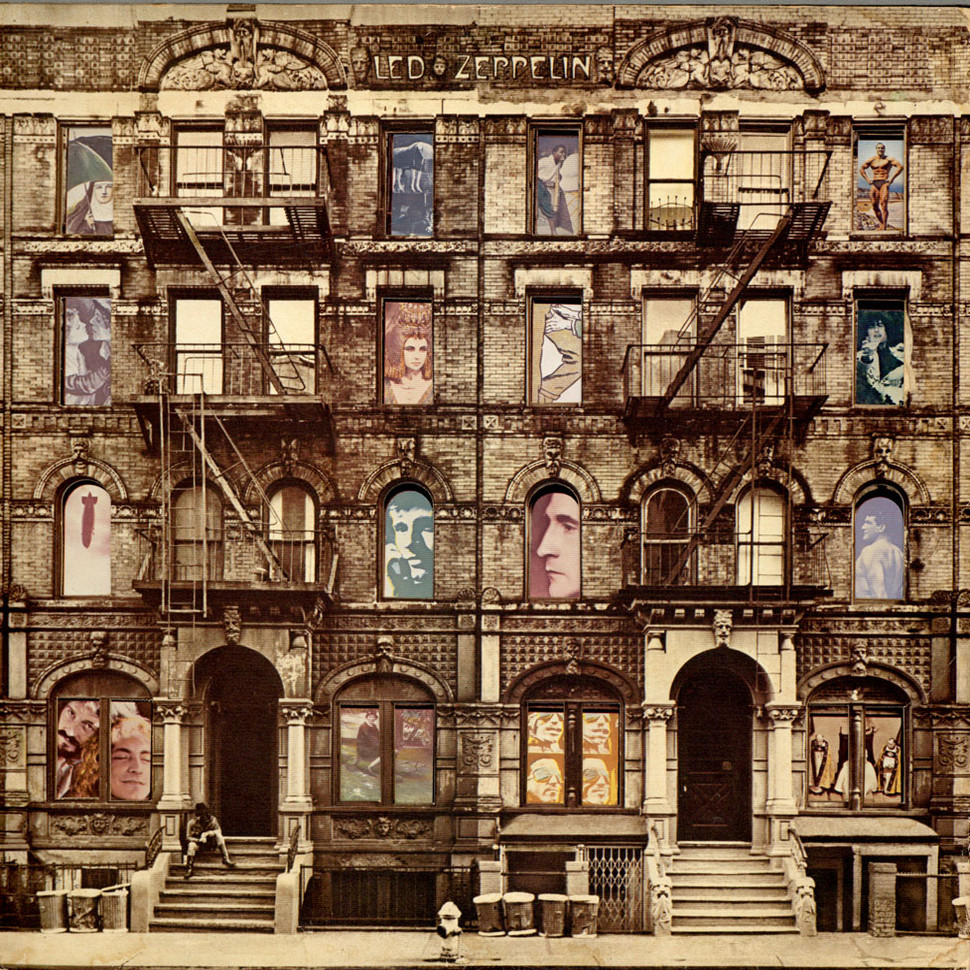

#7

Two adjacent five-story apartment buildings (with the fourth stories airbrushed out) in New York City’s East Village were used on the award-winning die-cut album cover for Led Zeppelin‘s 1975 extravaganza, “Physical Graffiti.” Designer Peter Corrosion used interchangeable inner sleeves to depict various people in the window slots. One sleeve uses letters in the windows that spell out the album title.

#8

For the cover of their next album, “Morrison Hotel,” in early 1970, The Doors hired legendary rock music photographer Henry Diltz to shoot them in front of the actual Morrison Hotel in downtown L.A. The manager refused permission, so they waited until the front desk clerk was called away before quickly taking positions in the front window while Diltz snapped a few frames to get what they wanted.

#9

Jeff Ayeroff and Norman Moore came up with the cover artwork using a variety of different photos of band members Stewart Copeland, Sting and Andy Summers, overlaid by horizontal stripes of the three primary colors. In one of more than 30 variations, the middle montage showed Sting reading a copy of Carl Jung’s book “Synchronicity,” on which The Police‘s 1983 LP was based.

#10

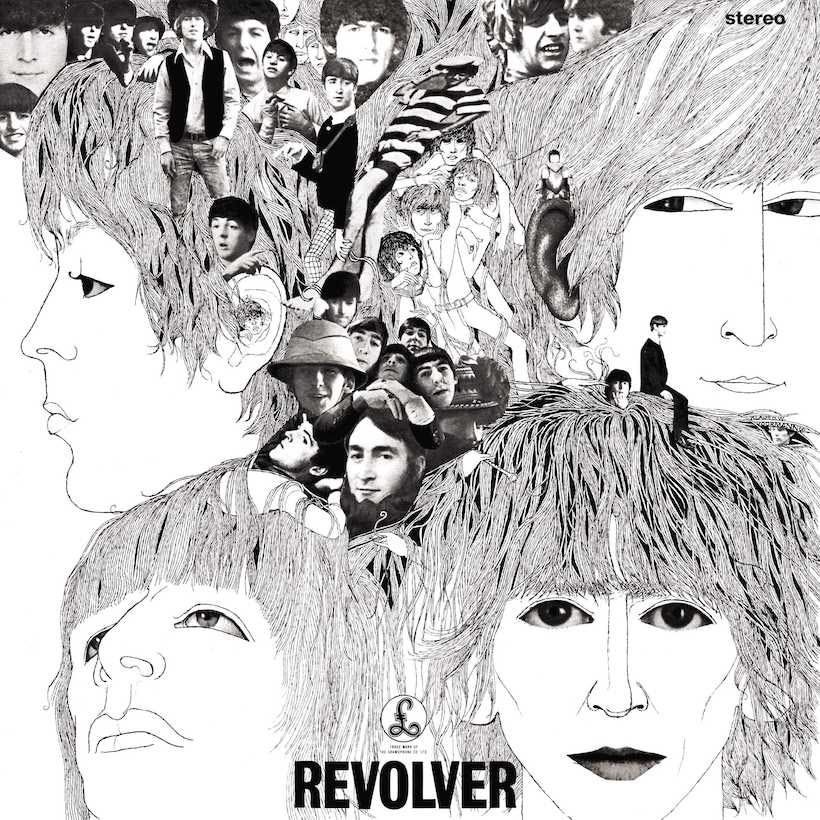

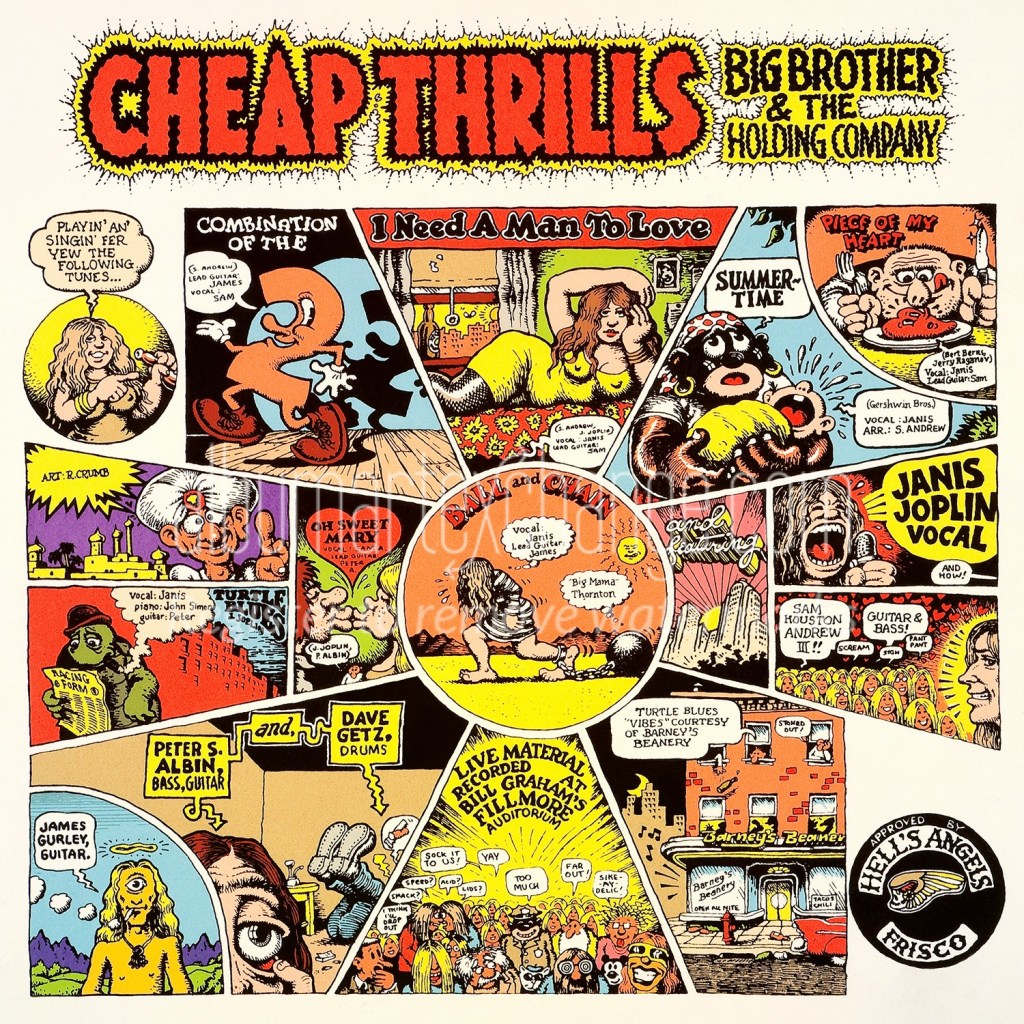

Big Brother and the Holding Company‘s lead singer, the incomparable Janis Joplin, was a huge fan of underground comic books. She commissioned the great Robert Crumb to illustrate the song titles and band members for the back cover art, but once she saw the result, Joplin insisted it be on the front cover. The album title (originally “Sex, Dope and Cheap Thrills“) was shortened by the record label.

#11

Elliot Landy rivaled Henry Diltz as the “go to” rock photographer in the late ’60s and early ’70s, shooting important covers for Bob Dylan (“Nashville Skyline”) and Van Morrison (“Moondance”) and portraits of Jimi Hendrix, Jefferson Airplane, Frank Zappa and others. His work appears on the covers of “Music From Big Pink” and “The Band,” the first two LPs by Robbie Robertson, Levon Helm and company.

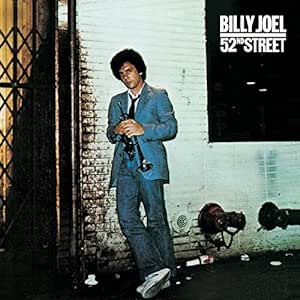

#12

For the cover of his 1978 jazz-influenced album “52nd Street,” Billy Joel was photographed leaning against the dingy side of the Griddle Coffee Shop at 7th Avenue and 52nd Street in Manhattan, once a popular hangout location for jazz musicians, and just a block away from the CBS Building and the studio where the album was recorded.

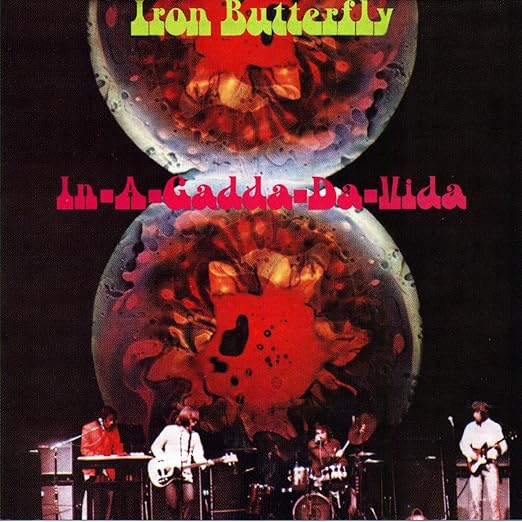

#13

Many psychedelic rock bands used oils and waters on a glass surface projected onto huge screens behind the bands to add trippy visuals to the acid rock music being performed. For the cover of their “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida” album in 1968, Iron Butterfly used an image by photographer Stephen Paley of the group on stage that year with the liquid light show behind them.

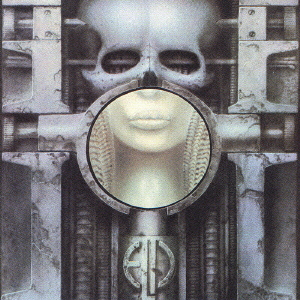

#14

Keith Emerson became fascinated with the “biomechanics” artwork of Swiss artist Hans Reudi Giger, and in 1973, Giger was commissioned to create two pieces to serve as an outer (mechanical male) cover and inner (human female) cover for the new Emerson, Lake & Palmer album, “Brain Salad Surgery.” Giger also designed a new ELP logo as part of the outer cover that was used on all subsequent releases.

#15

When John Lennon re-entered the public arena in 1980, he was adamant that his new songs be presented in partnership with the new offerings of his wife, Yoko Ono. The album, entitled “Double Fantasy,” alternated ballads and rockers from each artist, all focusing on their idealized romance. Ono selected acclaimed Japanese photographer Kishin Shinoyama to capture the loving couple in mid-kiss.

#16

The cover for Fleetwood Mac‘s ubersuccessful “Rumours” album bears some resemblance to the 1975 “Fleetwood Mac” album that precedes it. Photographer Herbert Worthington and designer Desmond Strobel again featured 6’6″ Mick Fleetwood’s beanpole frame, but this time he was paired with sultry songstress Stevie Nicks in her diaphanous stage garments, lending a ballet-like aura to the image.

#17

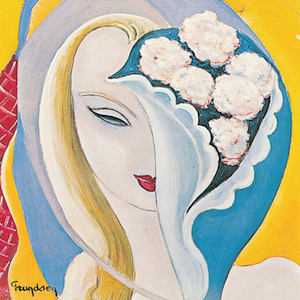

When Eric Clapton first spied “La Fille Au Bouquet,” a painting by French artist Émile-Théodore Frandsen de Shomberg, he saw a strong resemblance between the girl depicted and his obsessive love interest, Pattie Boyd Harrison, the subject of his brilliant tune “Layla.” The painting became the cover art for “Layla and Other Assorted Love Songs,” the 1970 double LP by Derek (Clapton) and The Dominos.

#18

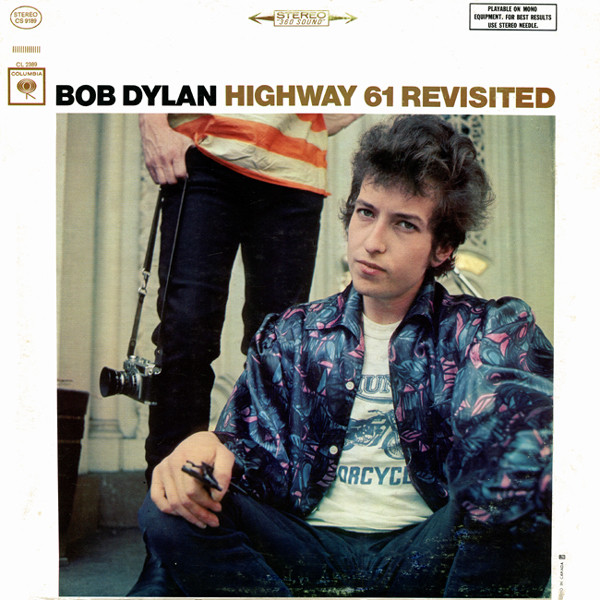

For his hugely influential 1965 LP “Highway 61 Revisited,” Bob Dylan was photographed sitting on the front stoop of manager Albert Grossman’s apartment in Gramercy Park in Manhattan. Photographer Daniel Kramer, who positioned Dylan’s cohort Bob Neuwirth behind Dylan “to give the shot extra color and depth,” urged Dylan to adopt an expression of “hostile moodiness” that fit his rebel image.

#19

Actors, statesmen, models, singers and celebrities of nearly every stripe were eager to be photographed by acclaimed portrait photographer Richard Avedon in the 1950-1990 era. Paul Simon and Art Garfunkel felt honored that Avedon accepted the assignment to shoot the duo for the cover of their “Bookends” LP in 1968. It was one of only a half-dozen album covers in which he was involved.

#20

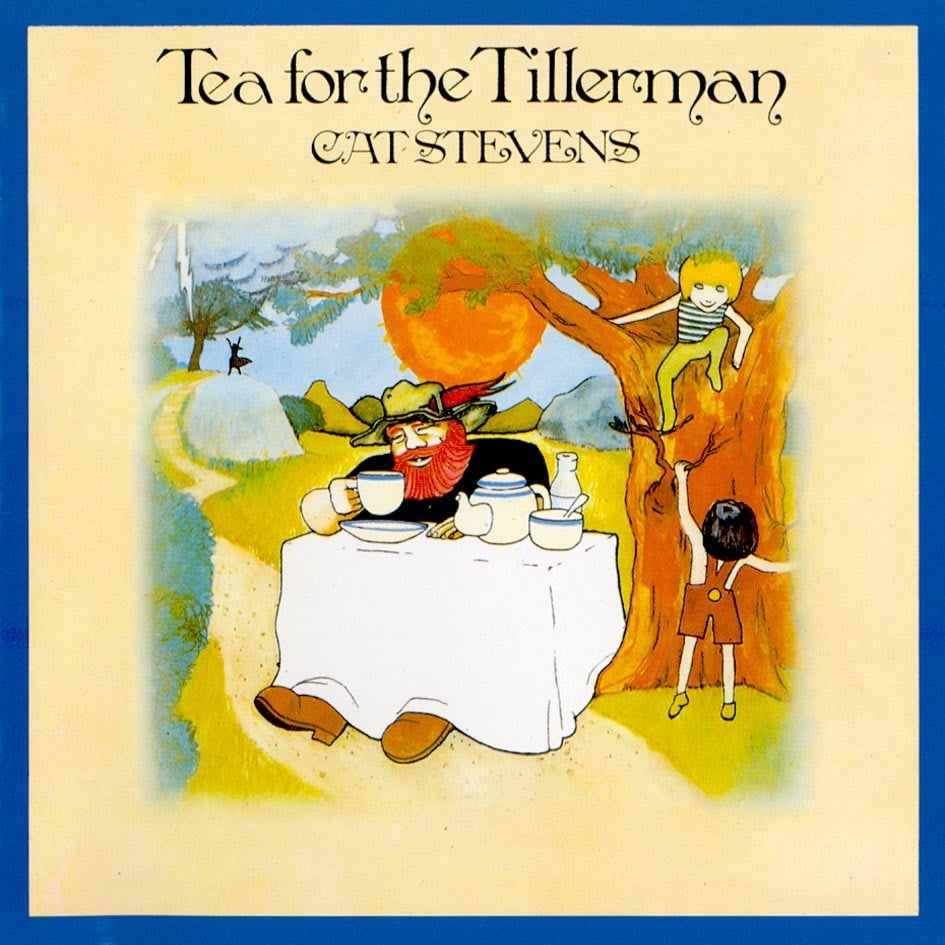

Steven Georgiou, later known worldwide as Cat Stevens and then eventually Yusuf, was a promising art student as well as a singer-songwriter. His two most popular albums — 1970’s “Tea For the Tillerman” and 1971’s “Teaser and the Firecat” — feature album cover artwork created by Stevens himself. He used children’s book illustration techniques to complement the gentle music and lyrics of his songs.

#21

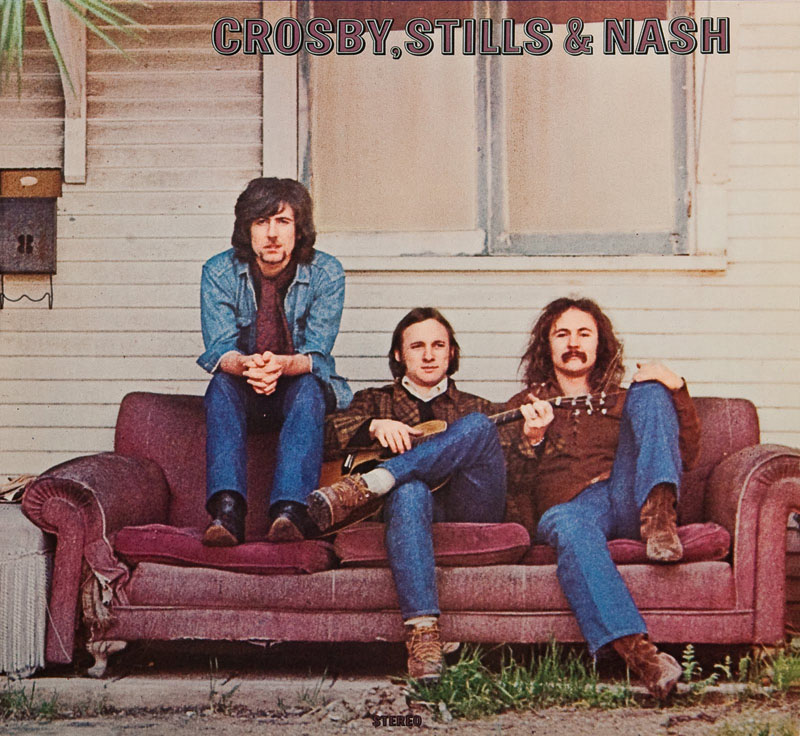

Henry Diltz’s talent shows up a second time in this indelible image of Graham Nash, Stephen Stills and David Crosby sitting on an abandoned couch in front of a condemned home in Hollywood. Realizing they’d been positioned out of order, they returned a few days later to reshoot, but the house had been razed. So the “Crosby, Stills and Nash” album went out as is in the spring of 1969.

#22

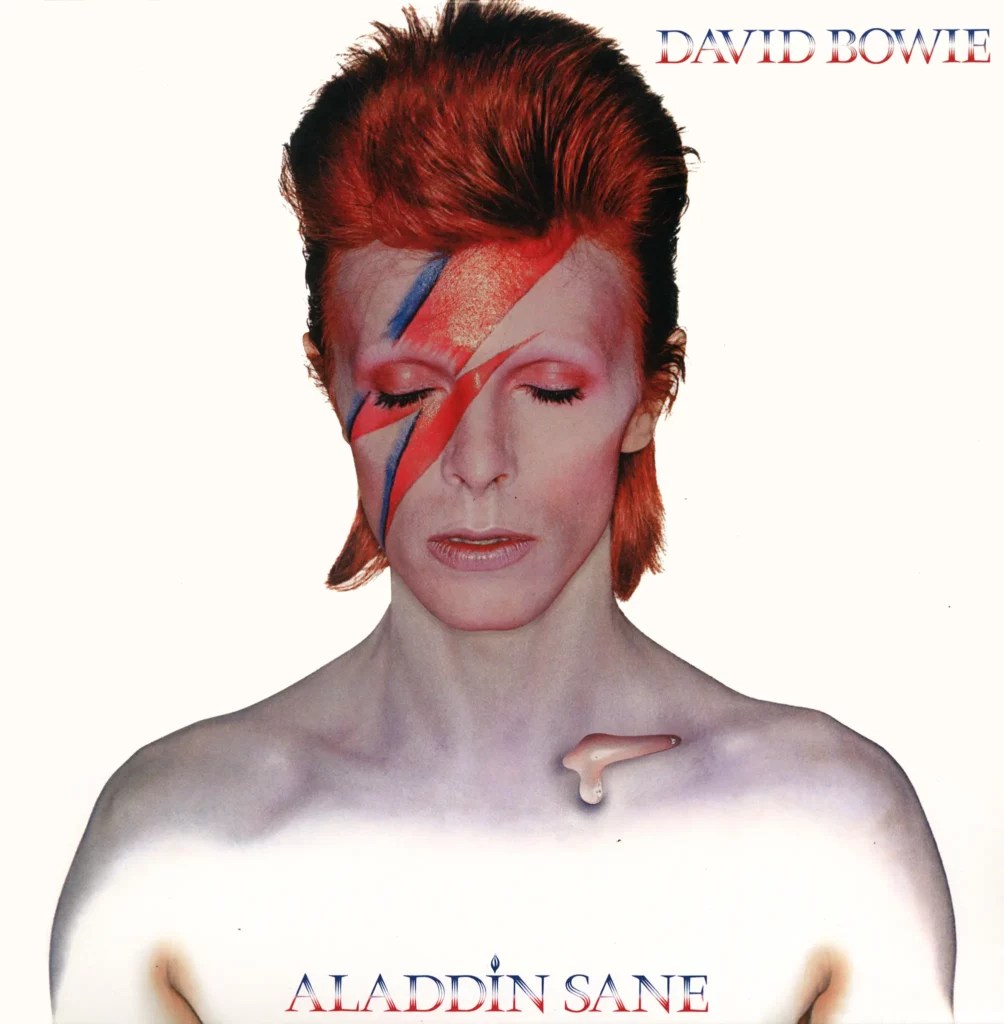

It’s one of the most iconic images of David Bowie‘s long career, but it was the only time he wore the striking thunderbolt face makeup. As the cover for the 1973 LP “Aladdin Sane,” the image maintained and enhanced his breakthrough “Ziggy Stardust” persona, with photographer Brian Duffy using an unprecedented seven-color system that made it the most expensive cover ever made up to that point.

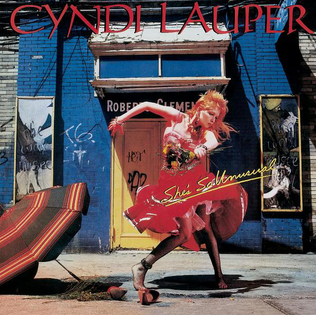

#23

Art designer Janet Perr won the 1985 Best Album Package Grammy for this boldly colorful presentation of Rolling Stone photographer Annie Leibovitz’s shot of Cyndi Lauper on Henderson Walk in Coney Island. For the “She’s So Unusual” cover, Lauper wore vintage clothing and accessories she found at Screaming Mimi’s, a vintage clothing shop near there where she once worked.

#24

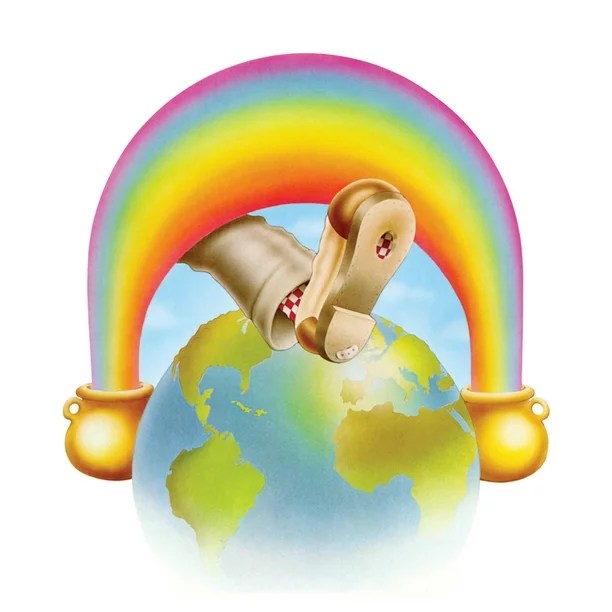

The design team of Alton Kelly and Stanley Mouse again worked with The Grateful Dead on the cover artwork for their superb 1972 triple live album “Europe ’72.” The triple-gatefold sleeve illustrations feature not only the familiar “truckin'” foot stepping across the Atlantic Ocean to Europe, but also, on the back cover, the “truckin’ fool” smashing an ice cream cone against his forehead.

#25

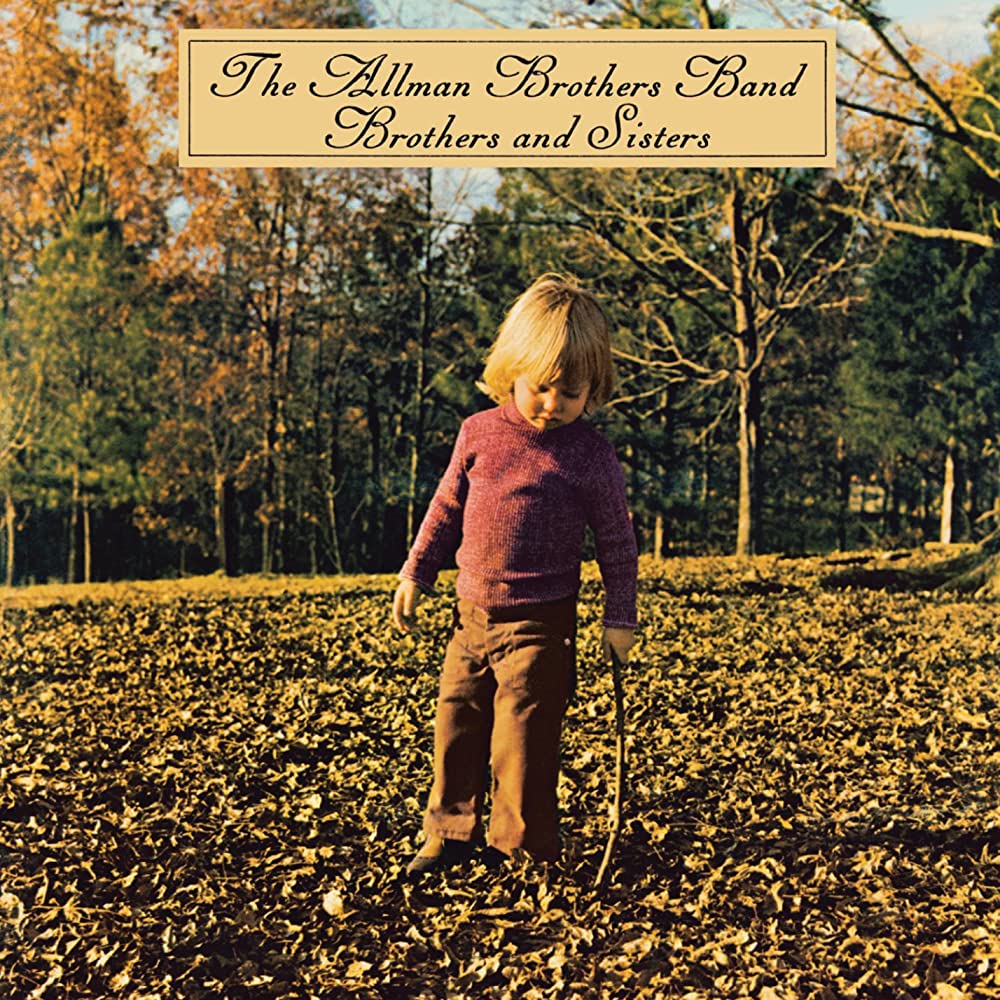

Photographer Dan Hudson Jr.’s bucolic photo of young Vaylor Trucks (son of drummer Butch Trucks) playing in the autumn leaves provides a stark contrast to the tension and grief that surrounded The Allman Brothers Band in 1973 following the deaths of Duane Allman and Berry Oakley. This shot, and a similar shot of Oakley’s daughter Brittany on the back, appear on their “Brothers and Sisters” LP.

****************************************