Bringing it all to a dramatic conclusion

When musical artists write and record songs for a new album, they often (but not always) take great care to consider the best running order. Which song would be an attention-getting leadoff track? Do the songs flow seamlessly (or at least not jarringly) from one to the next?

Putting an emphatic ending to the proceedings with the perfect closing track is a crucial consideration for the savviest of artists. On The Beatles’ stunning “Abbey Road,” they concluded a nine-song medley with “The End,” a whirlwind showcase of drums and dueling guitars before the final couplet, sung in harmony with orchestral strings, intones, “And in the end, the love you take is equal to the love you make.” Tying things up neatly with a bow, right? Well, actually, no. They punctured that storybook ending with a 30-second snippet called “Her Majesty” that had been removed earlier from the running order but serendipitously found its way onto the master tape after 15 seconds of silence.

A friend recently suggested I look at the best closing tracks on classic rock albums to come up with a dozen that do an excellent job of bringing an LP to a dramatic, fitting conclusion. It’s a very subjective list, to be sure. There are no doubt some fine examples of great final songs that appear on not-so-great albums, but I chose to hone in on the best closers that appear on iconic records from the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s. I’d be interested in hearing your comments and suggestions about songs I may have overlooked.

***************************

“A Day in the Life,” The Beatles, 1967

Most critics through the years have concluded that this unparalleled piece of music ranks as the very pinnacle of the 215 songs The Beatles wrote, and serves magnificently as the dramatic finale on their most iconic LP, “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band.” John Lennon brought the basic song to the studio, with lyrics that referenced a couple of newspaper items about a friend who’d died in a car accident and the number of potholes in the town of Blackburn. Paul McCartney had a little unfinished ditty that recalled his morning routine every school day (“Woke up, fell out of bed”), and they found a crafty way of merging the two fragments into one spectacular piece. The transition between them still stands as one of the most game-changing segues ever conceived — a symphony orchestra starting on the same note, gradually moving up at their own pace, getting increasingly louder until they arrived tumultuously at the same note 24 bars later. As McCartney put it: “We needed something really amazing, a total freak-out.” The result was almost frightening in its intensity, and The Beatles loved the results so much that they repeated it at the song’s denouement, capped with all four Beatles simultaneously hitting the same E chord on pianos, letting the note ring out for 40 seconds to fadeout.

“Won’t Get Fooled Again,” The Who, 1971

This hugely influential song was originally intended as the final track for “Lifehouse,” the follow-up to The Who’s 1969 rock opera “Tommy.” Pete Townshend struggled to bring the “universal chord” concept to fruition and abandoned the project, instead taking the best nine tracks he’d developed and turning them into the more traditional LP “Who’s Next,” released in 1971. Lyrically, “Won’t Get Fooled Again” was Townshend’s dismissive take on the counterculture and its revolutionary rhetoric, summarized in the line “Meet the new boss, same as the old boss.” Said Townshend, “I wrote it as a reaction to the Abbie Hoffmans of the world. I was very cynical about whether all the demonstrating would make a difference. I was saying, ‘Nothing has changed and nothing is going to change.'” Musically, the track is an astonishing eight-minute tour de force of The Who at their best, featuring Townshend’s innovative, comprehensive integration of the then-new synthesizer into a rock song arrangement. With producer Glyn Johns manning the boards, the tune turned into The Who’s signature song, and became the show closer in live performances. Even the much shorter single version, severely edited from 8:32 to 3:36, had enormous power, reaching #9 on US charts.

“Let It Rain,” Eric Clapton, 1970

When the short-lived supergroup Blind Faith dissolved in 1969 after one album and a short tour, Clapton found himself eager to hang out and jam with the loose confederation of musicians known as Delaney and Bonnie and Friends, who had been the warmup act on the tour. In particular, Bonnie Bramlett proved to be a welcome songwriting collaborator, and she and husband Delaney urged Clapton to showcase what they felt was a very credible singing voice. Clapton was reluctant, but when the time came to record the new batch of songs that had been written, he agreed to give it a go. The resulting debut solo LP, titled simply “Eric Clapton,” featured Clapton’s vocals on every track. J.J. Cale’s “After Midnight” and Leon Russell’s “Blues Power” got a lot of airplay, but the standout track is, without question, the closer, “Let It Rain,” which began life with different lyrics and the title “She Rides.” Featuring Russell’s rollicking piano, Stephen Stills chipping in with a sublime guitar part in the middle bridge, and the guys who would become his bandmates in Derek and the Dominos (drummer Jim Gordon, organist Bobby Whitlock and bassist Carl Ladle) providing the foundational groove, “Let It Rain” boasts a lovely melody, which Clapton sings beautifully. What really makes it, though, is the smokin’ guitar solo in the two-minute outro, one of the best of his career.

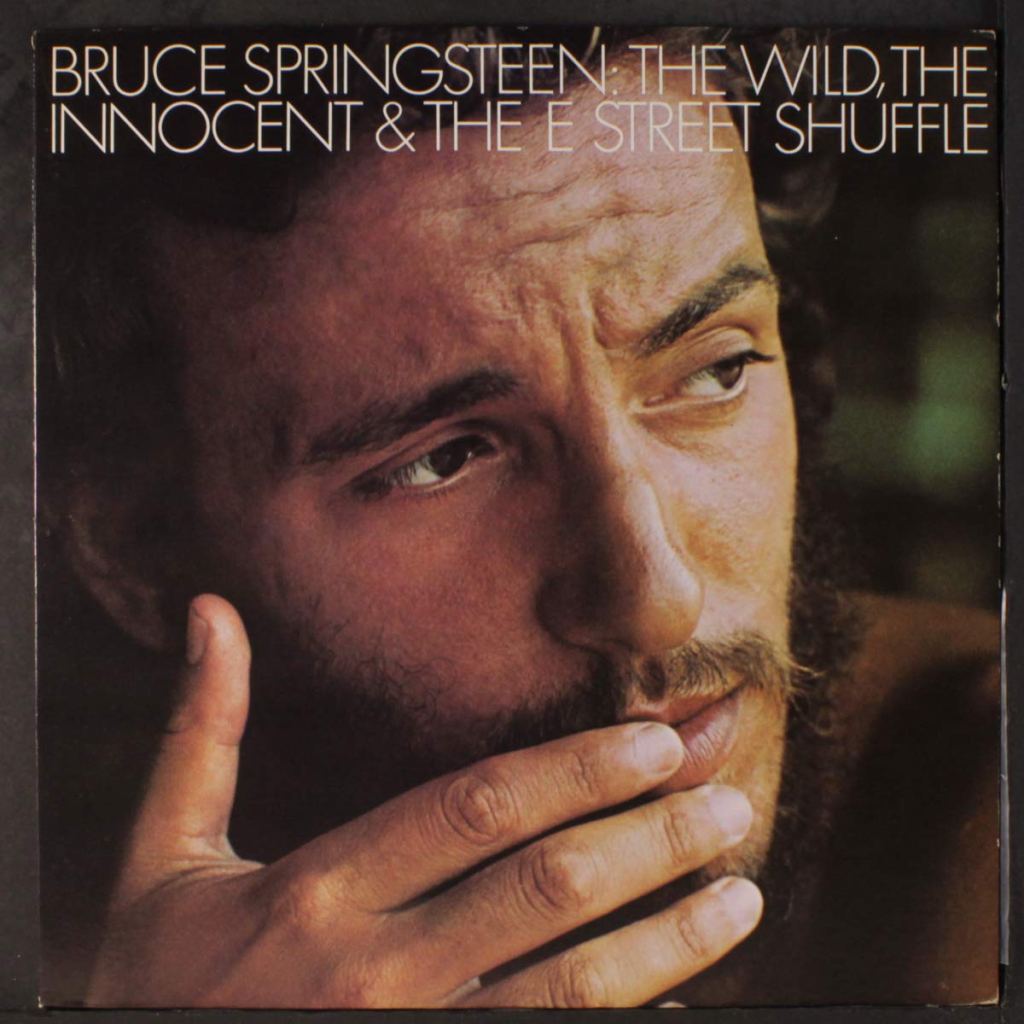

“Jungleland,” Bruce Springsteen, 1975

After two fine albums that were largely ignored when first released, Springsteen and The E Street Band knew their next release might be their last if they didn’t knock it out of the park. They labored for more than a year to come up with the eight songs that comprise “Born to Run,” a seismic album that is now indelibly etched in the annals of rock and roll. It’s a “street opera” of sorts, as Springsteen explains: “‘Thunder Road’ introduces the album’s central characters and its main proposition: Do you want to take a chance? It lays out the stakes you’re playing for and sets a high bar for the action to come. Then comes ‘Tenth Avenue Freeze Out,’ the story of a rock ‘n’ soul band and our full-on block party. Side two opens with the wide-screen rumble of ‘Born to Run,’ then the Bo Diddley beat of ‘She’s the One’ before we cut to the trumpet of Michael Brecker as dusk falls and we head through the tunnel for ‘Meeting Across the River.’ From there, it’s the night, the city and the spiritual battleground of ‘Jungleland’ as the band works through musical movement after musical movement, culminating in Clarence Clemons’s greatest recorded sax solo. The knife-in-the-back wail of my vocal outro, the last sound you hear, finishes it all in bloody operatic glory.” No doubt about it — “Jungleland” leaves the listener feeling drained, but in awe.

“How Many More Times,” Led Zeppelin, 1969

From the ashes of The Yardbirds, Led Zeppelin was born as the dream child of guitar virtuoso Jimmy Page, who recruited his friend and session musician John Paul Jones on bass, then identified vocalist Robert Plant and drummer John Bonham as the final pieces of the blues/rock band he envisioned. Page had a couple of songs he’d developed with The Yardbirds, plus two Willie Dixon blues tunes, but the rest of the debut LP was fashioned by the foursome in the studio, sometimes using songs written by others but without giving them credit (“Babe I’m Gonna Leave You” in particular). The album closer, the titanic “How Many More Times,” had been improvised around Howlin’ Wolf’s “How Many More Years,” going through various snippets of standards like “The Hunter” and “Rosie” and even a quasi-bolero passage. On this track and the other lengthy piece, “Dazed and Confused,” Page took to using a violin bow on his Les Paul guitar during the middle section, with the eight-minute piece coming together live in the studio. “How Many More Times” was a perfect way to wrap up that incredible first album, and served as the band’s show-stopping final song during their earliest tours as well.

“Brain Damage/Eclipse,” Pink Floyd, 1973

Since 1971, Roger Waters had been mulling over the idea of writing a whole album devoted to challenging themes like conflict, time, greed, madness and death. In particular, Waters said he became morbidly fascinated by the mental illness that sent Pink Floyd’s original leader, Syd Barrett, over the edge and out of the band he founded. Of the set of songs Waters wrote, the centerpiece — eventually slotted to close the album — was a mesmerizing track first known as “Lunatic.” He called it “Dark Side of the Moon” for a while until that became the album title, and he finally settled on “Brain Damage.” The creepy nature of the lyrics (“You lock the door and throw away the key, there’s someone in my head, but it’s not me…”), complete with maniacal laughter, was perfectly complemented by a ghostly vocal and hypnotic arrangement. Early in the sessions, Waters knew he wanted to have “Brain Damage” segue directly into another piece called “Eclipse,” a two-minute song that would wrap up the album with a heartbeat and a disembodied voice that observes, “There is no dark side of the moon, really; matter of fact, it’s all dark…” Released in 1973, it’s one of the best-selling albums of all time.

“Burn Down the Mission,” Elton John, 1970

The remarkable “Tumbleweed Connection” album was an ambitious song cycle that attempted to capture the mood of the American Wild West, which had always fascinated John’s lyricist, Bernie Taupin. Songs like “Ballad of a Well-Known Gun,” “Country Comfort” and “Talking Old Soldiers” are vignettes with detailed character sketches Taupin came up with based on novels he had read describing the late 1800s in the Western U.S. The most richly rewarding and enduring track of them all is “Burn Down the Mission,” the finale which tells the sad tale of a bitter man from a poor community oppressed by a rich and powerful landowner. The man is driven to rally the townsfolk to take revenge by torching the buildings on the property, but the attempt fails and he is taken away to face the consequences. Musically, it’s one of the most complicated works of Elton John’s entire career, with abrupt tempo shifts and four key changes. The track opens with John alone on piano and vocals, eventually building to a faster, jazzier middle bit with fuller instrumentation, then repeating that contrast in the song’s second half. He often included it in his concert setlist, and was one only two non-singles performed on his 2022-23 Farewell Tour.

“Gold Dust Woman,” Fleetwood Mac, 1977

As acclaimed as the 11 tunes are that make up “Rumours,” the stories behind the making of the album are the stuff of legend. Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham had broken up and were taking vicious swipes at each other in the lyrics of their new songs; Christine McVie had begun a new relationship in the wake of her divorce from John McVie; and Mick Fleetwood’s marriage to Jennie Boyd was hanging by a thread. After a year-long tour in support of their 1975 “Fleetwood Mac” album, the LP had finally reached #1, so expectations were high and the pressure was on to deliver a blockbuster. Complicating matters further was the easy availability and amped-up daily use of cocaine before, during and after the sessions. Nicks chose to write about this insidious influence in the evocative, foreboding “Gold Dust Woman,” which closed the album. The take selected for the finished record was recorded at 4 a.m. in a darkened studio with Nicks’s head wrapped in a black scarf to veil her senses to tap deep emotions. The instrumentation and vocals built slowly from quiet beginnings to an all-out frenzy as the track faded to black. “Everybody was doing coke regularly,” she recalled. “It was always around, and I had a real serious flash of what this stuff could be, of what it could do to you, and I imagined that it could overtake everything, never thinking in a million years that it would overtake me.”

“The Circle Game,” Joni Mitchell, 1970

Mitchell’s first two LPs, “Song to a Seagull” and “Clouds,” offered just a hint of what was to come in her unparalleled songwriting and recorded output. The arrangements were as sparse as they get — generally only Joni singing and accompanied by one instrument (guitar, piano or dulcimer). That began to change on her remarkably mature third album, “Ladies of the Canyon,” which featured other players using cello, clarinet, flute, sax and percussion. The songs were more challenging as well — the sprightly “Conversation” and “Big Yellow Taxi,” the gorgeous melodies of “Morning Morgantown” and “For Free,” her haunting electric-piano version of “Woodstock.” Perhaps most eye-opening was the album’s finale, “The Circle Game,” a simple, philosophical gem she had written four years earlier at just 22. She has since revealed that the song focuses on her Canadian friend Neil Young, who had turned 21 and was no longer welcome to play a favorite club that catered to teens. “He felt terrible that he was now ‘over the hill’ in his mind,” she remembers, “and so he wrote ‘Sugar Mountain,’ a lament for lost youth. I thought, God, you know, if we get to 21 and there’s nothing after that, that’s a pretty bleak future, so I wrote a song for him, and for myself, just to give me some hope.” The words tell a gentle tale of a boy who is “captive on the carousel of time,” but she reassures him, and all of us, that “There’ll be new dreams, maybe better dreams, and plenty / Before the last revolving year is through.”

“You Can’t Always Get What You Want,” The Rolling Stones, 1969

As they were working on the songs that would become their celebrated “Let It Bleed” album at the end of 1969, Mick Jagger mentioned, “I like the way The Beatles used orchestral instruments as something extra to prolong the ending of ‘Hey Jude.’ We may do something like that.” Sure enough, The Stones experimented with French horn and the London Bach Choir, which ultimately gave “You Can’t Always Get What You Want” an anthemic quality as the album’s final track. What started as a simple song Jagger had written on acoustic guitar in late 1968 evolved into an extraordinary elegiac hymn set to a rock arrangement. Violent songs like “Gimme Shelter” and “Midnight Rambler” set the tone of the album, and some critics interpreted the lyrics as a comment on “the end of the overlong party that was The Sixties.” Desperate lines like “I went down to the demonstration to get my fair share of abuse…” fit that overall mood, but there’s an undeniably uplifting quality to the band’s fine recorded performance and the sense of optimistic realism inherent in the philosophy of the song’s main idea: “You can’t always get what you want, but if you try sometimes, you just might find, you’ll get what you need.”

“The End,” The Doors, 1967

There may not be a darker closing track on a rock album than this shattering 12-minute piece that concludes The Doors’ brilliant self-titled debut. Considered a precursor of the “gothic rock” genre that became popular in some circles in the 1970s, “The End” uses guitar, organ and Jim Morrison’s menacing vocal delivery to provide a bold take on the “Oedipus complex” that was a key part of Freudian psychology at the time. As keyboardist Ray Manzarek has said, “Jim wasn’t actually saying he wanted to kill his father and rape his mother. He was re-enacting a bit of Greek drama. It was theatre!” Indeed. In 1970, Morrison said in an interview, “When I sang, ‘My only friend, The End,’ I was saying sometimes the pain is too much to examine, or even tolerate. That doesn’t make it evil, or necessarily dangerous. But people fear death even more than pain, which is strange, because life hurts a lot more than death. At the point of death, the pain is over. So I guess it is a friend.” Filmmaker Francis Ford Coppola regarded the piece as sufficiently harrowing to use to dramatic effect during the introduction of his 1979 Vietnam War epic “Apocalypse Now.”

“Rock ‘N’ Roll Suicide,” David Bowie, 1972

When Bowie first dreamed up the song cycle that would become “The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and The Spiders From Mars,” he devised a narrative in which an androgynous, alien rock star comes to Earth before a looming cataclysmic disaster to deliver a message of hope. However, after accumulating a large following of fans and being worshipped as a messiah, Ziggy eventually dies as a victim of his own fame and excess. The character, as portrayed by Bowie in live performances throughout 1972 and 1973, was meant to symbolize an over-the-top, sexually liberated rock star and serve as a commentary on a society in which celebrities are idolized. “Starman” and “Suffragette City” stole the spotlight as the two featured tracks on radio, but the entire album ranks as one the most complete and concise concepts ever committed to vinyl. The album’s closing number, “Rock and Roll Suicide,” details his final collapse, not in blood, but as a doomed figure who requests that the audience “give me your hands” before self-imploding. It was the last of the album’s 11 numbers to be recorded, using strings and horns to give the track a majesty and a grand sense of staged drama not previously seen/heard in rock music.

******************************

The Spotify list below includes 11 of the 12 closing tracks discussed above, but frustratingly, Joni Mitchell refuses to give permission for her songs to be played on the Spotify platform, which is the one I’ve always used here at “Hack’s Back Pages.” My apologies for the omission of her rendition of “The Circle Game”; instead, I dropped in Tom Rush’s fine cover version so it could at least be represented.