Say I’m old fashioned, say I’m over the hill

It’s time once again for another dive deep into the long-ignored waters of the albums of the 1960s and 1970s to remind you all of the great hidden music to be found there.

Classic rock stations are happy to overexpose you to the same two or three or four songs from a band’s repertoire that you know all too well. You know the tired old format: If they play Led Zeppelin, you can be sure it’ll be “Stairway to Heaven,” “Whole Lotta Love,” “Black Dog,” “Immigrant Song,” “Fool in the Rain” or “D’yer Ma’ker” (or, if you’re lucky, “Kashmir”). But good God, there are another five dozen great Zep tracks just sitting there, waiting to be exhumed!

My job here, as I see it, is to select a dozen or so great “lost gems” from classic albums and entice you to dig them out, look them up, and savor their deliciousness.

I urge you to send me your suggestions of other excellent forgotten tracks I can include in future blog posts about these wonderful old songs.

Rock on, everybody!

****************************

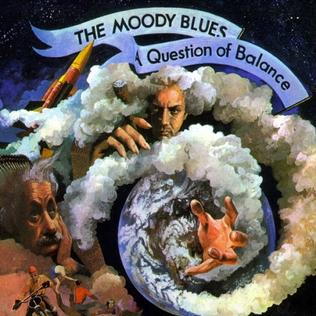

“It’s Up to You,” The Moody Blues, 1970

It’s no secret that guitarist/singer Justin Hayward has always been the songwriting wizard of The Moody Blues, one of the true pioneers of what became known as progressive rock. Their collaboration with the London Symphony Orchestra on 1967’s “Days of Future Passed” (including the eventual worldwide hit “Nights in White Satin”) was an unprecedented merger of disparate musical genres. By 1970, the band had already shown a keen knack for crafting album-length song cycles, and their #3-ranked LP “A Question of Balance” was the best yet, an intelligent, challenging musical lesson in coping with a world ravaged by war and environmental indifference. Songs like the hit single “Question” and “Dawning is the Day” were Hayward compositions that asked sobering queries about our future, and the clincher, “It’s Up to You,” is the appealing, hopeful apex, urging us all to get involved and help save the planet from extinction.

“Georgia,” Boz Scaggs, 1976

Born in Ohio, raised in Texas, Scaggs met up with Steve Miller as a teenager, and they eventually collaborated in San Francisco on The Steve Miller Band’s first two albums, “Children of the World” and “Sailor.” Boz went out on his own in ’69 with a self-titled debut that included the legendary 10-minute “Loan Me a Dime,” anchored by a smokin’ lead guitar performance by the late great Duane Allman. Always rooted in R&B, Scaggs’ solo albums leaned toward blue-eyed soul, culminating in 1976 in the trendsetting #2 LP “Silk Degrees,” with four hit singles, most notably “Lowdown” and “Lido Shuffle.” The LP also included Scaggs’ fine ballad “We’re All Alone,” made famous by Rita Coolidge. The hidden gem on this album could be the sensual “Harbor Lights,” which is music to undress to, but I prefer the joyous, upbeat “Georgia,” which, by the way, is a tribute to a woman, not the state.

“Chain Lightning,” Steely Dan, 1975

You can make a convincing case that Steely Dan’s seven albums during its 1972-1980 period represented the most consistently excellent music of the Seventies. By far the most underrated of the those LPs, in my opinion, is 1975’s “Katy Lied.” The band’s songwriting masterminds, Donald Fagen and Walter Becker, have forlornly disparaged the album because of a studio mishap that allegedly damaged the master tapes and rendered it “unlistenable” (to their audiophile ears), but frankly, I can’t figure out what they’re talking about. To me, it sounds incredible, full of killer pop/jazz hooks, stunning vocals, standout instrumental passages (dig the Phil Woods sax solo on “Doctor Wu”) and some of the best dark-humor lyrics in the entire Dan catalog. Almost any track would be a worthy candidate for this “lost gems” list, but I’m going with the sublime, blues-based “Chain Lightning.”

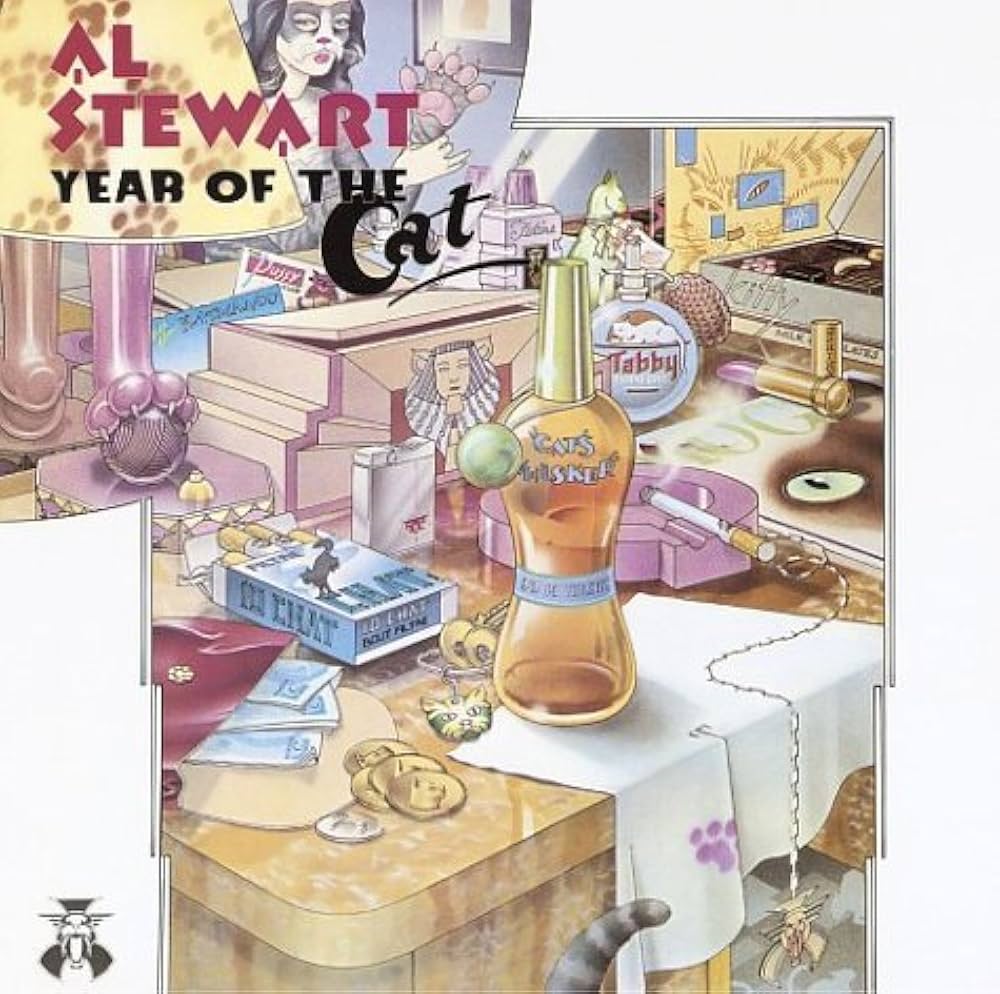

“On the Border,” Al Stewart, 1976

The singer-songwriter era — popularized by James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, Cat Stevens, Carole King and others — had peaked by 1976. Still, there were promising acoustic-based artists in the US and England who continued to press forward, and Glasgow-born Al Stewart was one of them. He had released four albums in Britain between 1967 and 1972, without much success, and two more LPs (1973’s “Past, Present and Future” and 1975’s “Modern Times”) saw modest exposure on US radio playlists. And then came his seventh and best LP, “Year of the Cat,” in 1976. Some found his distinctly nasal voice off-putting, but there was no denying his finely structured story-songs, beautifully performed and produced on this album, with nary a weak moment. The title track fought through the relentless onslaught of disco music at the time to reach #8 on the Billboard charts, but the track that has always blown me away is “On the Border,” featuring the fine Spanish guitar work of Peter White.

“The Only Living Boy in New York,” Simon and Garfunkel, 1970

At the time of the January 1970 release of the award-winning “Bridge Over Troubled Water” LP, the primary buzz was all about the shimmering title anthem, and the interesting choices for follow-up singles, “El Condor Pasa” and “Cecilia.” We’d already heard and embraced another album track, “The Boxer,” as a landmark single nearly a year earlier. But there were three or four other outstanding songs on the album that got no airplay whatsoever, and the best of those, “The Only Living Boy in New York,” ranks among my top four or five Paul Simon compositions of all time. It tells the story of Tom (a veiled reference to Art Garfunkel’s late ’50s persona, when the duo was known as Tom and Jerry) heading to Mexico to act in a movie (“Catch-22”), leaving his partner behind in New York to work alone on their next album. It aggravated their tenuous relationship to the point where Simon chose to end it and go solo a year later. But what a gorgeous final statement, only recently resurrected during the duo’s 2004 “Old Friends” reunion tour.

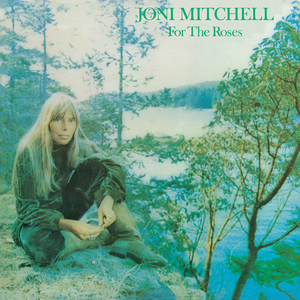

“Woman of Heart and Mind,” Joni Mitchell, 1972

Nobody can write an autobiographical confession song like Miss Mitchell, whose first six or seven albums (1968-1974) are a virtual diary of her love life and childhood reveries. Usually with only spare guitar or piano accompaniment, Joni offered up searing portraits of herself and her various relationships on memorable songs like “Blonde in the Bleachers,” “I Had a King,” “My Old Man,” “See You Sometime,” “Little Green,” “A Case of You” and “Car on a Hill.” It’s difficult to pick which one of her many poignant deep album tracks to bring out into the light here, but I’ve settled on the incredible “Woman of Heart and Mind” from her 1972 “For the Roses” LP. Joni cuts to the bone by sizing herself up this way: “You think I’m like your mother, or another lover, or a sister, or the queen of your dreams, or just another silly girl…” It’s a devastatingly personal piece of work, and beautiful in its simplicity.

“Samba Pa Ti,” Santana, 1970

Mention the Santana LP “Abraxas” and everyone automatically thinks of the #1 hit “Black Magic Woman” (actually written and first recorded by Peter Green’s original version of Fleetwood Mac in 1968), or maybe the Latino-flavored “Oye Como Va.” Carlos Santana had assembled a delicious brew of African-American, Caucasian and Latino musicians in San Francisco that enjoyed an explosive national debut at Woodstock in 1969, and “Abraxas” was a marvelous smorgasbord of their best work. Often overlooked, though, was the band’s mellower side on smoldering instrumental tracks like “Samba Pa Ti,” where Carlos’s expressive guitar led the way through a sensual first part into a more upbeat second half that leaves listeners emotionally drained.

“Winter,” The Rolling Stones, 1973

Following the brilliant four-LP dominance of “Beggars Banquet,” “Let It Bleed,” “Sticky Fingers” and “Exile on Main Street,” the Stones found themselves pretty much out of songs, out of vibes and out of gas. For their mostly disappointing 1973 LP “Goat’s Head Soup,” Jagger and Richards conjured up the acoustic gem “Angie” (which became yet another #1 single for them), and the horn-driven stomper “Doo Doo Doo Doo Doo (Heartbreaker),” but the rest of the album seemed flat and uninspired. The obvious exception was “Winter,” a compellingly melancholy collaboration between Jagger and second guitarist Mick Taylor, who ended up leaving the band a year later (replaced by Ronnie Wood). Taylor’s layered-chord approach offered a striking contrast to the choppy riffs of Richards, who didn’t appear on the track at all.

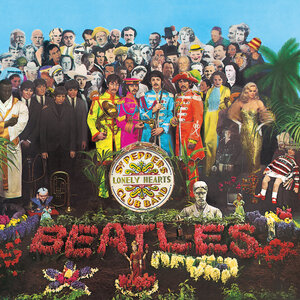

“Within You Without You,” The Beatles, 1967

I remember, at age 13, pointedly skipping this strange, otherworldly song whenever I lowered the needle onto Side Two of the “Sgt. Pepper” LP, but years later, I developed a deep respect for George Harrison’s thoughtful, sitar-driven piece and its spiritually cosmic lyrics. The colorful phantasm of “Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds,” wistful storytelling of “She’s Leaving Home,” communal warmth of “With a Little Help From My Friends” and unparalleled brilliance of “A Day in the Life” all combine to give the “Sgt. Pepper” album its legendary status as one of the best in rock history. But take the time to consider Harrison’s boundary-stretching musical arrangement, and his all-knowing words derived from Eastern philosophy: “Try to realize it’s all within yourself, no one else can make you change, and to see you’re really only very small, and life flows on within you and without you…” Many critics labeled the song as “the conscience of the album” and “its ethical soul,” and I’m inclined to agree.

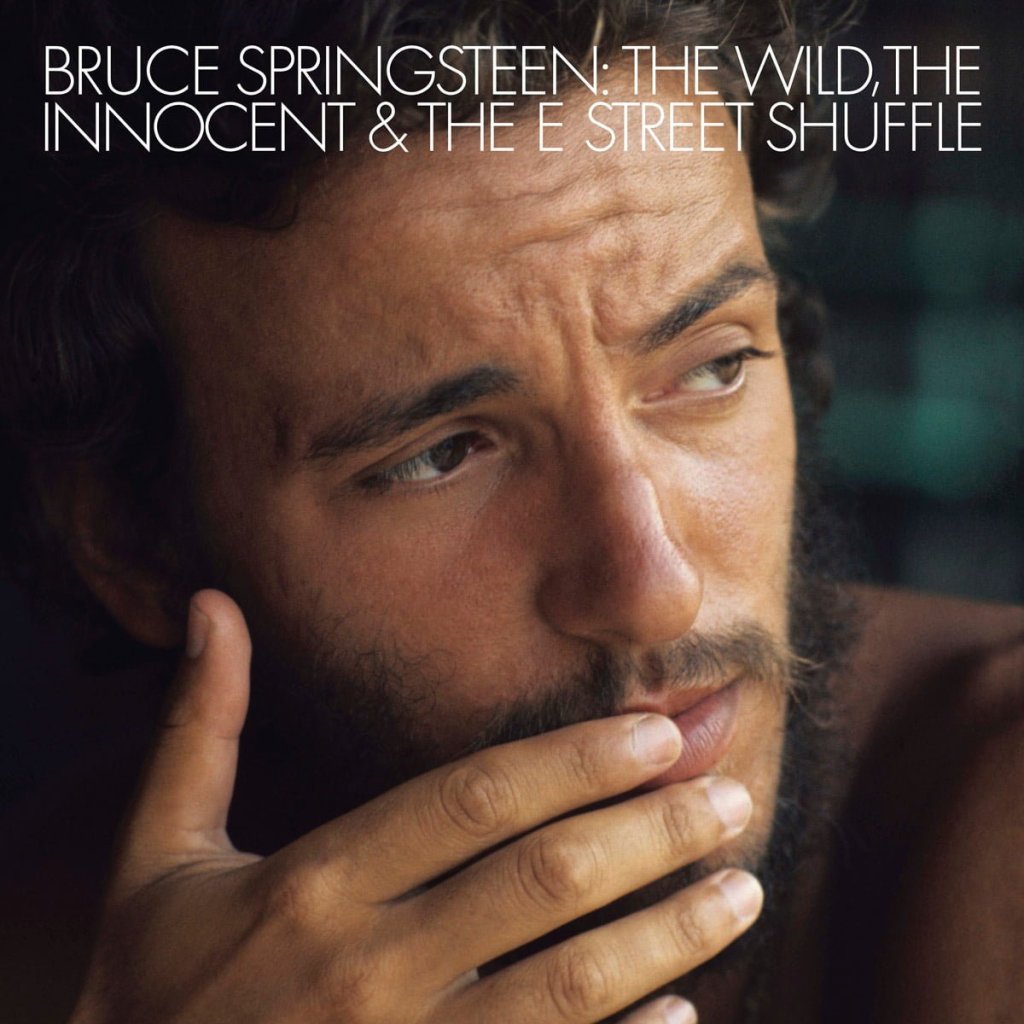

“Kitty’s Back,” Bruce Springsteen, 1973

It’s hard to imagine the rock landscape without the dominance of Bruce Springsteen’s presence, but in 1973-1974, he and The E Street Band were still struggling mightily for exposure, recognition and stardom. The Boss’s first LP had stalled at #60 on Billboard’s album charts. His second LP, the magnificent “The Wild, The Innocent and the E Street Shuffle,” was also largely ignored at the time, despite amazing, epic songs like “Rosalita,” “Asbury Park, Fourth of July (Sandy)” and “Incident on 57th Street.” In the years since, “Rosalita” has been properly acknowledged as a titanic track full of Bruce’s early exuberance, but we mustn’t overlook the wonder that is “Kitty’s Back,” a seven-minute cauldron of simmering emotion and over-the-top joy, carried by a relentless beat and tight ensemble playing, led by Clarence Clemon’s monstrous sax riffs.

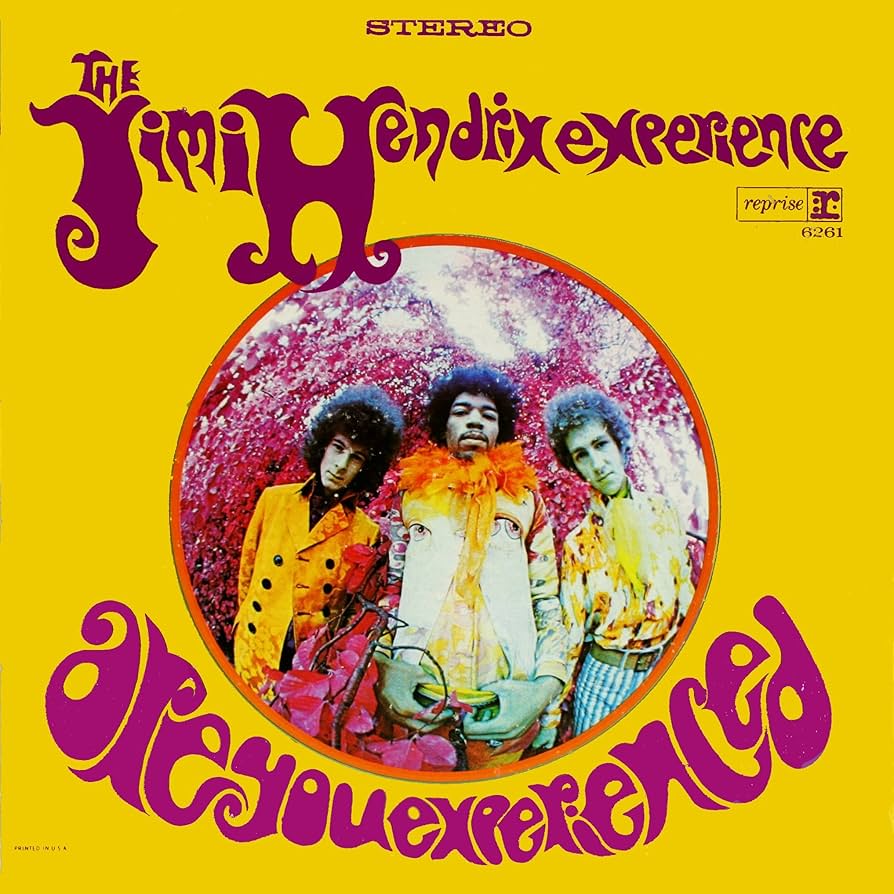

“Fire,” Jimi Hendrix Experience, 1967

What a firestorm Jimi Hendrix was! The Seattle-born guitarist moved to London in 1966, formed his legendary trio, and recorded one of the most incendiary debuts of all time, “Are You Experienced?” By mid-summer, the rock music world knew all about this virtuoso, thanks to a show-stopping appearance at the Monterey Pop Festival and the amazing music from that first LP. The singles “Hey Joe,” “Purple Haze” and “The Wind Cries Mary” had all reached Top Five in the UK, but the fickle US singles market failed to embrace any of them. However, the rock music scene was changing that year, and fans began preferring albums over singles, and they sent “Are You Experienced?” to #5 on US album charts, the first of four consecutive Top Five LPs here before he died prematurely in 1970. One of the most astonishing tracks, rarely heard on the radio, is the compact 2:34-length song “Fire,” which features The Experience’s guitar/bass/drums mix at its best, particularly the work of drummer Mitch Mitchell.

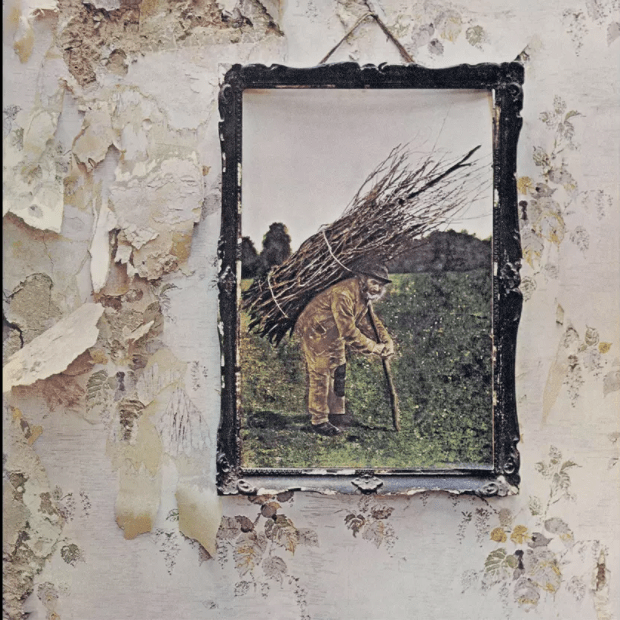

“When the Levee Breaks,” Led Zeppelin, 1971

By 1971, Led Zep had become the undisputed kings of hard rock, both on record and in concert, and they were eager for their fourth LP to blow everyone’s minds. With “Stairway to Heaven” leading the way, the album — released without an official title, but known as “Zoso,” “Led Zeppelin IV” or even “Untitled” — is still regarded as their masterpiece. The complicated syncopation of “Black Dog,” the rollicking onslaught of “Rock and Roll,” the band’s quieter acoustic side beautifully represented by the mandolin-heavy “The Battle of Evermore” and the Page/Plant tribute to Joni Mitchell, “Going to California” — it all came together majestically. But for many true fans, the earthshaking moment on the LP is the seismic closer, “When the Levee Breaks,” a song which actually dates back to the 1930s and legendary blues woman Lizzie “Memphis Minnie” Douglas. John Bonham’s drums alone — recorded in a cavernous stone atrium/stairwell in an English countryside castle — are unlike anything you’ve ever heard before or since.

More “lost gems” to come! There are SO MANY waiting to be rediscovered!