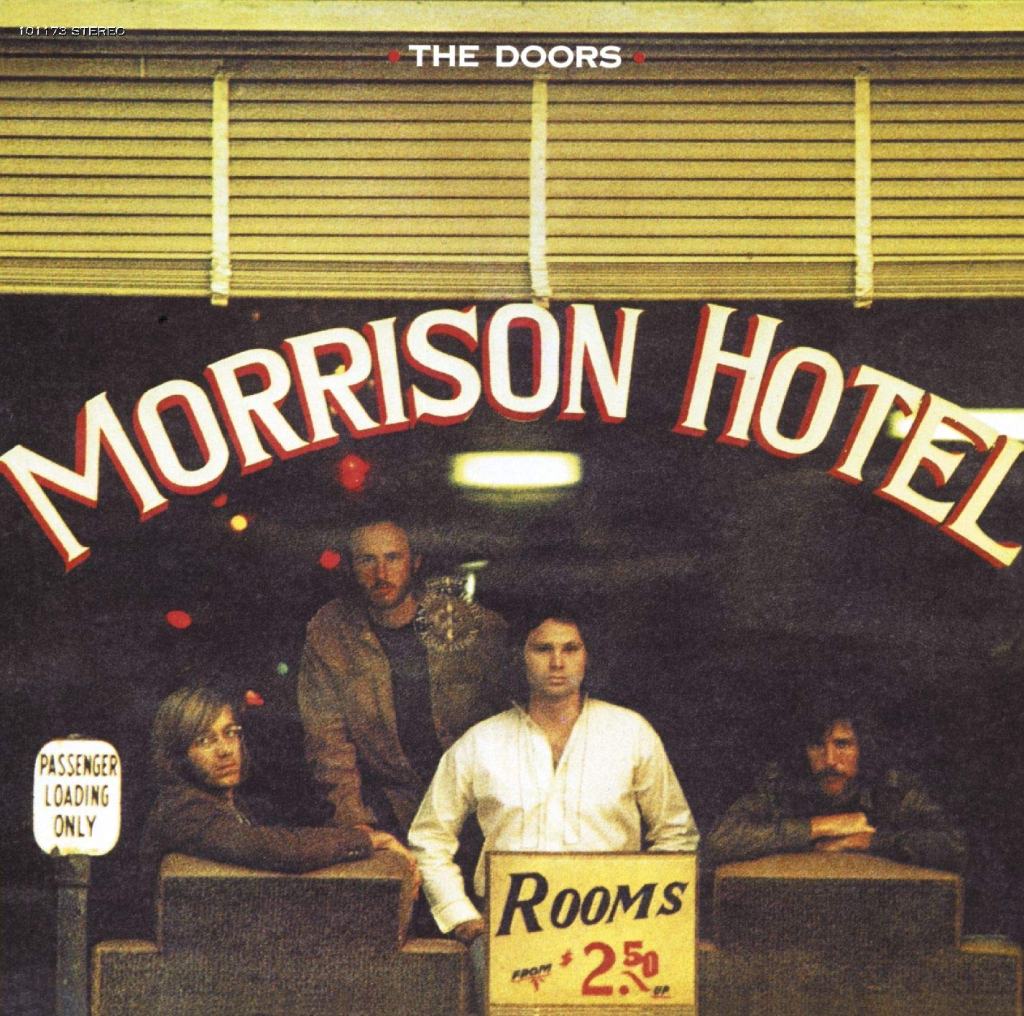

Waiting for you like hidden treasures

(Reprinted from Oct 30, 2015 post)

It’s time once again to delve deep into some of the classic albums of the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s and find those superb “deep tracks” that the radio stations never play. So many of the albums that topped the charts back then have three, maybe four songs that get all the airplay even though there are some jewels just sitting there, waiting to be rediscovered and savored.

This blog has always been dedicated to shining a bright light on a number of neglected tracks from famous albums. I also enjoy drawing attention to great songs from LPs that were NOT major-selling albums. But for now, come with me as we expose the wonderful “diamonds in the rough” among the top-selling albums of the glorious decades of 40, 50, 60 years ago.

There’s a Spotify playlist at the end to soak in these great tunes as you read along.

*************************

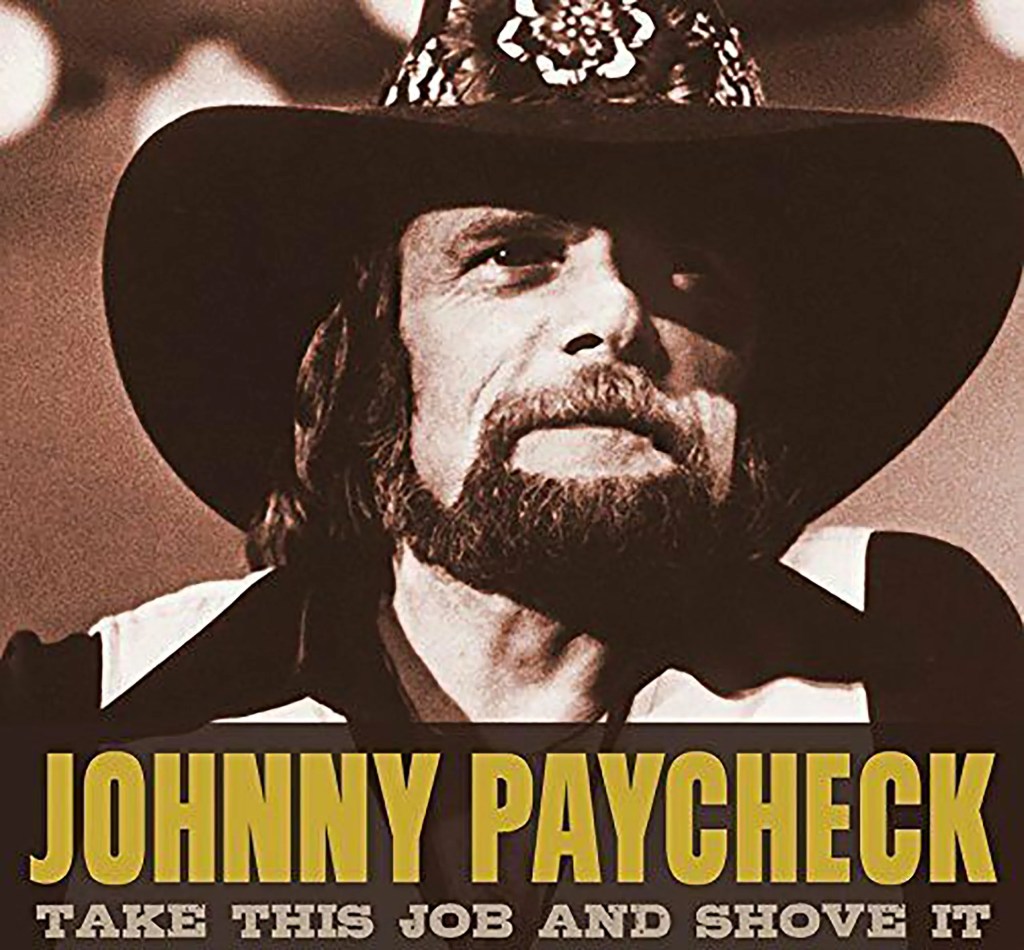

“Listen,” Chicago, 1969

When the band that would be known as Chicago released their debut, the extraordinary “Chicago Transit Authority” in April 1969, they felt they had so much good material that it should be a double album, which takes chutzpah for a new band to claim. But they were right — not only were there enough worthy tracks to warrant a double LP, their sound was a revelation, a shrewd merger of rock and big band, with fiery guitar solos, exuberant trumpet/trombone/sax passages, and three vocalists each capable of leading the way through instantly likable hit songs like “Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is,” “Questions 67 and 68” and “Beginnings.” But like most albums chock full of hits, there are excellent tracks that never got the attention they deserved. On “CTA,” I nominate “Listen,” the shortest song on an album full of 5-minute-plus tracks, led by Robert Lamm’s great vocals, a strong bass line from Peter Cetera and the ever-present horn section.

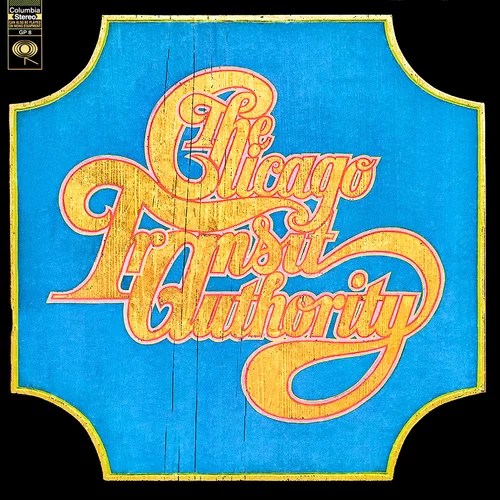

“Just a Job to Do,” Genesis, 1983

Genesis was a fantastic theatrical progressive rock outfit from 1969-1975, with the amazing Peter Gabriel as their vocalist/showman throughout that period…but then he felt the need to leave, spend family time, yada yada, and maybe branch out on his own. Meanwhile, the remaining members of Genesis — keyboardist Tony Banks, guitarist Mike Rutherford, and drummer/vocalist Phil Collins — soldiered on, and ultimately became a hugely successful commercial act, with multiple hit singles in the ’80s. Their 1983 album “Genesis” had hits like “Mama” and “That’s All,” but the highlight for me from this period was the track about the reluctant hit man, “Just a Job to Do” (“…and bang! bang! bang! and down you go…”), which has a relentless beat and an irresistible arrangement that just won’t quit. Genesis was certainly two different bands, with and without Gabriel, but the second one surely had its moments…

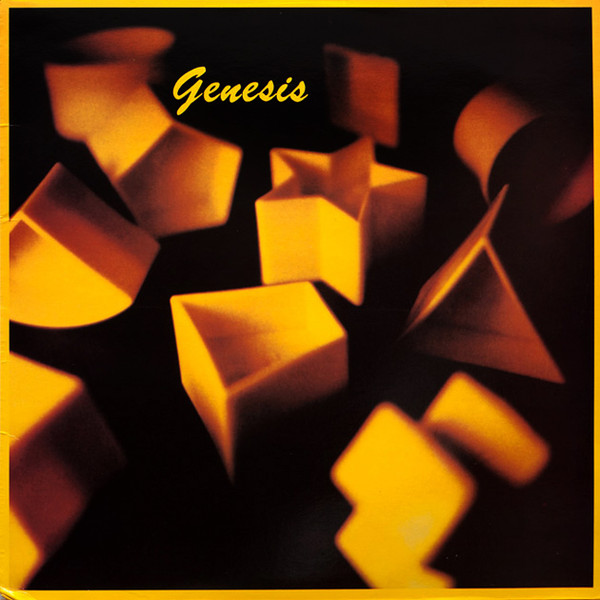

“Peace Frog,” The Doors, 1970

I love the Doors, and inhaled their first two albums especially, and their swan song, “LA Woman,” but somehow never caught on to the “Soft Parade”/”Morrison Hotel” period for whatever reason. Buried deep on the 1970 “Morrison Hotel” album is a great little track called “Peace Frog,” which my daughter Rachel did a very cool dance to in 2010 in her jazz dance class/recital, and I rediscovered the song amidst the overplayed Doors tracks on classic rock radio. I recently was pleased to hear it again on the season premiere of the James Spader TV series “The Blacklist,” which proves how classic tracks have staying power and can resurface when and where you least expect them. I urge you to dig this one out of the archives.

“I Give You Give Blind,” Crosby Stills and Nash, 1977

CSNY had always been a volatile mix. David Crosby, Steve Stills, and Graham Nash had already brought an excess of talent and ego to the party when they first formed in 1969, so when they added the moody and enigmatic Neil Young to the mix, the result was a predictable implosion, and they soon went their own ways. So, what a delight when, in 1977, the original trio reconvened with the superb “CSN,” which included Nash’s hit “Just a Song Before I Go” and the haunting “Cathedral,” and Crosby’s “Shadow Captain” and “In My Dreams,” and Stills’ “Fair Game” and “Dark Star.” All great songs — in fact, there’s not a dud on the album — but the one I find most spellbindng is the Stills closer, “I Give You Give Blind,” which includes not only the trademark CSN three-part harmonies but a fiery, full-band attack not often heard on a CSN recording, a sound sparked by Stills’ guitar work. Fantastic.

“Been Too Long on the Road,” Bread, 1970

Bread?! Yes, Bread. Everybody has their guilty pleasures, and Bread is one of mine. I was 15 and full of puppy love when they showed up, and I loved their hits like “Make It With You,” “It Don’t Matter to Me” and “Baby I’m-a Want You.” But Bread was more than just the syrupy ballads of David Gates; they had some album tracks with tasty guitar licks and a rock backbeat. Witness the minor hits “Mother Freedom” and “The Guitar Man.” Hidden deep on their 1970 album “On the Waters” was a delicious little song called “Been Too Long on the Road,” which had a catchy melody and mature lyrics about how touring can kill a relationship. Make fun of me if you must, but at least check out this song. It’s a keeper.

“Telegraph Road,” Dire Straits, 1982

Mark Knopfler, one of the great guitar players of my lifetime, will forever be known mostly for his Dire Straits debut single “Sultans of Swing” and the 1985 MTV hit “Money for Nothing.” But his output is so much broader and deeper than those two monster hits. Since Dire Straits’ breakup in 1994, he has released a dozen amazing records full of tasty guitar passages and Celtic folk material, and I could go on and on about the worthiness of his solo stuff. Still, let’s just examine the incredible tracks that make up the six Dire Straits studio albums: “Down to the Waterline,” “Lady Writer,” “Romeo and Juliet,” “Skateaway,” “Your Latest Trick,” “Brothers in Arms,” “Calling Elvis,” “Planet of New Orleans,” and many many more. The one that stands out most for me, though, is “Telegraph Road,” the 15-minute masterpiece from their 1982 album, “Love Over Gold.” It starts quietly, builds for a while, gets quiet again, and then hits a point just past halfway through where it goes into a relentless crescendo that leaves your jaw scraping the floor once it finally fades out. Do yourself a favor and put this one on when you’ve got a 15-minute nighttime drive home ahead of you.

“Do What You Want, Be What You Are,” Hall and Oates, 1976

For my money, Daryl Hall and John Oates never topped the incredible blue-eyed soul classic “She’s Gone,” released in 1973 on the duo’s overlooked second album, “Abandoned Luncheonette.” Of course, they went on to become the most successful pop duo of all time in the late ’70s/early ’80s with “Sara Smile,” “Rich Girl,” “Private Eyes,” “I Can’t Go For That,” “Maneater” and many more. Buried on their 1976 LP “Bigger Than Most of Us” is a super sexy slow song called “Do What You Want, Be What You Are,” on which Hall hits high notes no man should be able to reach. This beautifully produced track is music to undress to.

“Let It Roll,” George Harrison, 1970

The triple album “All Things Must Pass” got a lot of attention, largely because the quiet ex-Beatle had substantially eclipsed his compatriots’ first solo albums, and because his hit single, “My Sweet Lord,” was simply effervescent. Clearly, he’d been sitting on a stockpile of great songs while waiting for the chance to come out from underneath the shadow of the Lennon-McCartney songwriting axis to shine in his own way. The album was chock full of great songs, including hits like “What Is Life” and “Awaiting On You All,” but to me, the unsung hero on the album is “Let It Roll (The Ballad of Sir Frankie Crisp”), which would have fit quite nicely among the tracks on the celebrated Beatles’ “White Album” two years earlier, when it was written.

“Punky’s Dilemma,” Simon and Garfiunkel, 1968

Director Mike Nichols was enamored with the work of Simon and Garfunkel and wanted Simon to write songs for his coming-of-age film “The Graduate” in 1967. Simon obliged with 3-4 songs, but Nichols rejected them, instead preferring to use “The Sounds of Silence,” “Scarborough Fair” and other existing songs from the S&G catalog in the background of his film. Simon was successful in getting “Mrs. Robinson” into the film in abbreviated form (because he hadn’t finished it yet). But left on the side of the road were amazing songs like “Overs” (about a marriage that had reached its end) and the winsome track “Punky’s Dilemma,” about a young man who wants to be anything (even a Kellogg’s corn flake or an English muffin) instead of a draftable college graduate in the late ’60s. The song ended up on the #1 1968 album “Bookends.”

“Murder By Numbers,” The Police, 1983

Between 1978 and 1983, The Police just kept getting better and better, starting with “Roxanne” and “Message in a Bottle” and improving with “Don’t Stand So Close to Me” and “Every Little Things She Does is Magic.” The trio of drummer Stewart Copeland, guitarist Andy Summers and bassist/singer/songwriter Sting (Gordon Sumner) peaked with their #1 album (and swan song) “Synchronicity” in 1983, which featured “King of Pain,” “Wrapped Around Your Finger,” the title track and the international #1 hit, “Every Breath You Take.” Left off the vinyl version but included on the CD was the sleeper classic “Murder By Numbers,” a creepy but compellingly great track about a serial killer.

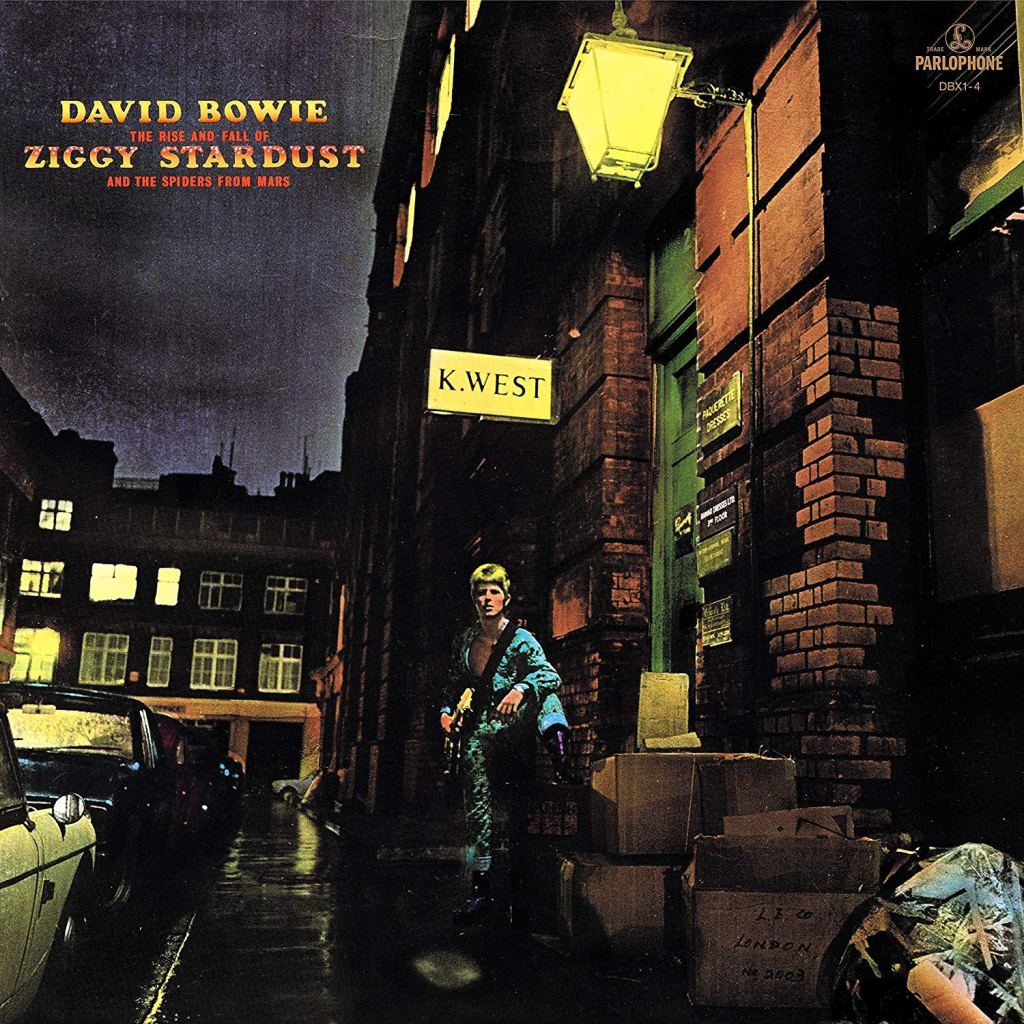

“Rock and Roll Suicide,” David Bowie, 1972

The enigmatic “chameleon of rock” was still relatively unknown in the US in 1972 when he made an indelible impression as the androgynous stage persona called Ziggy Stardust, an orange-haired rocker from another planet who single-handedly invented “glam rock.” David Bowie went on to adopt other personas over the decades, some commercially successful, others defiantly not, but he will always be known most for “The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars,” one of the most astounding records in rock history. “Suffragette City” and “Starman” got most of the airplay, but the incredible finale, “Rock and Roll Suicide” (“YOU’RE NOT ALONE! GIMME YOUR HANDS!”), leaves the listener gasping for breath when it ends with emphatic violins.

******************************