Songs to see you through the end of summer

As summer winds down, I’m feeling a little wistful, a little relaxed, and my deep dive into “lost classics” of the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s is consequently leaning toward the mellower choices this time around.

The rockers among my readers may fail to recognize some of these selections, or even the artists who recorded them. But that’s the fun of lost classics — even though they were recorded 50+ years ago, sometimes they’re brand-new songs to you because they came in under your radar at the time.

I hope you find these tunes to your liking.

************************

“Tell Me What You Want,” The Doobie Brothers, 1974

I think it’s safe to say that every album The Doobies released has at least one “lost classic” — a deep track that got little airplay but is still well worth our time and attention. The band’s fourth LP, “What Were Once Vices Are Now Habits,” will forever be known for its first #1 hit, “Black Water,” and the minor single “Eyes of Silver,” but there are about a half-dozen other strong tunes to explore. I’ve always enjoyed Pat Simmons’ engaging, mostly acoustic “Tell Me What You Want,” featuring the sweet pedal-steel work of Jeff “Skunk” Baxter in the outro. Baxter was then still a full-time member of Steely Dan, but as that group evolved into a duo with multiple guest musicians, he would soon make the jump to join The Doobies’ lineup.

“You’re Only Lonely,” J.D. Souther, 1979

If the lush harmonies you hear throughout this soothing track sound like those of The Eagles, that’s because the voices belong to Glenn Frey, Don Henley and Don Felder, plus Jackson Browne and Phil Everly for good measure. These gents were happy to help their friend John David Souther on his 1979 solo LP because he was an honorary Eagle, having co-written such hits as “Best of My Love,” “New Kid in Town” and “Heartache Tonight.” (He also co-wrote and co-sang “Her Town Too” with James Taylor in 1981.) “You’re Only Lonely” — a tribute of sorts to Roy Orbison’s 1960 classic, “Only the Lonely” — reached an impressive #7 on the US pop chart at a time when disco and New Wave were dominant.

“Still Believe,” Michael Tomlinson, 1987

Tomlinson came up out of the Austin, Texas, music scene in the mid-’80s, offering a pleasing acoustic style that caught the attention of certain radio program directors, particularly “relaxing radio” like The Wave. That’s where my friend Mark first heard Tomlinson’s song “All is Clear,” prompting him to buy his 1989 LP, “Face Up in the Rain,” and also his earlier album, “Still Believe.” I borrowed these records and enjoyed several standout tracks, most notably the positivism behind the lyrics of “Still Believe.” Tomlinson grew frustrated with record labels and corporate takeovers of radio stations and chose to withdraw from the business, but he later established his own private label and continues to write and record new music.

“It Doesn’t Have To Be That Way,” Jim Croce, 1973

Croce’s story is such a sad one, ending prematurely in a plane crash just as his years of hard work were beginning to pay off. After two hits in 1972 (“You Don’t Mess Around With Jim” and “Operator”) and a #1 hit in the summer of 1973 (“Bad, Bad Leroy Brown”), he was poised to join the top ranks of singer songwriters with his album and title song (“I Got a Name”) until fate intervened. Several posthumous singles were released — “Time in a Bottle” (another #1), the #9 hit “I’ll Have to Say I Love You in a Song” and, one of my favorites in his catalog, the poignant “It Doesn’t Have To Be That Way,” with Christmas-flavored lyrics and even the use of handbells.

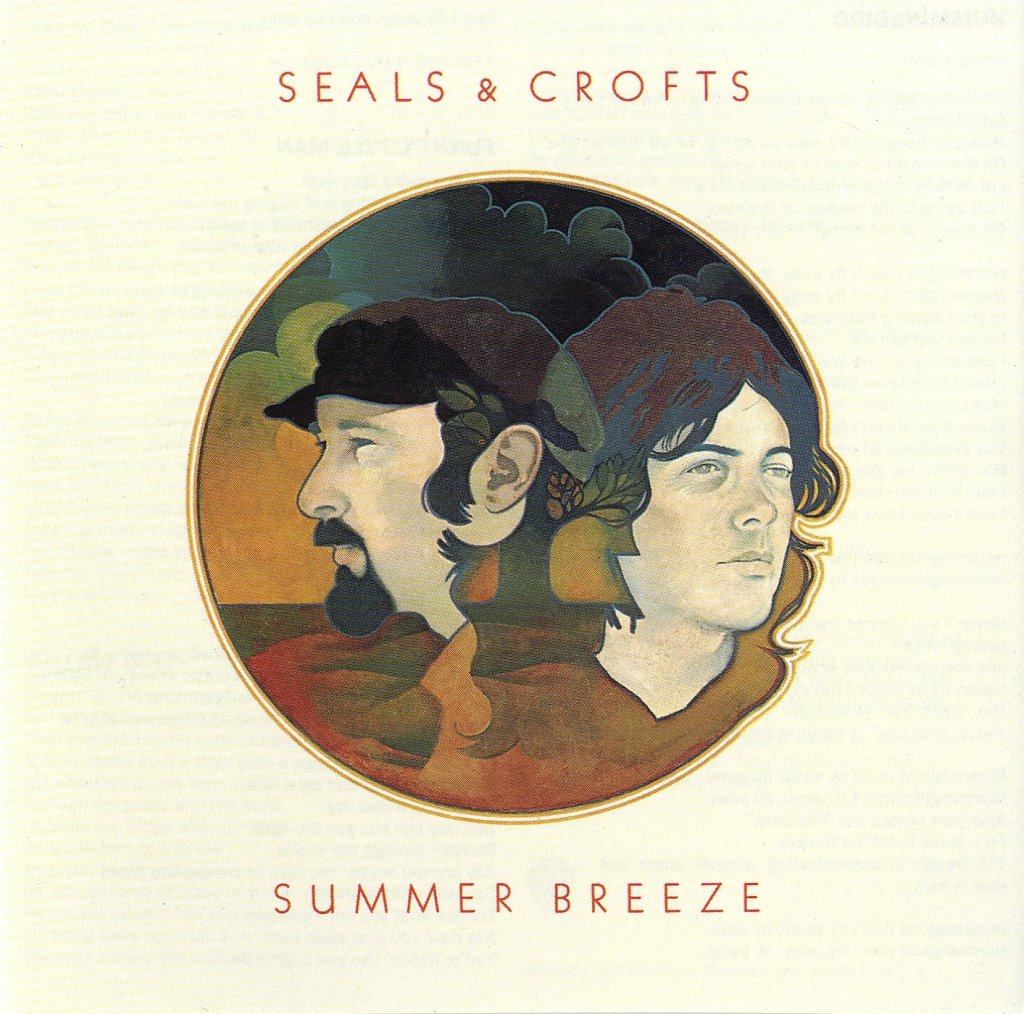

“The Euphrates,” Seals and Crofts, 1972

I remember being so knocked out by this duo’s first hit, “Summer Breeze,” that I pretty much ran to the record store to pick up the album of the same title. I found a delightful collection of melodic songs brimming over with spiritual lyrics espousing a life of selflessness and optimism. The voices of Jim Seals and Dash Crofts, the instruments (guitars and mandolin, mostly) and professional production give these tracks a majestic sweep. Buried on side two is a real sleeper called “The Euphrates,” which references the historic river running from Turkey through Syria and Iraq into the area formerly known as Mesopotamia: “The deep, deep river. The wide, wide river. The long, long river. Spiritual river. The river of life…”

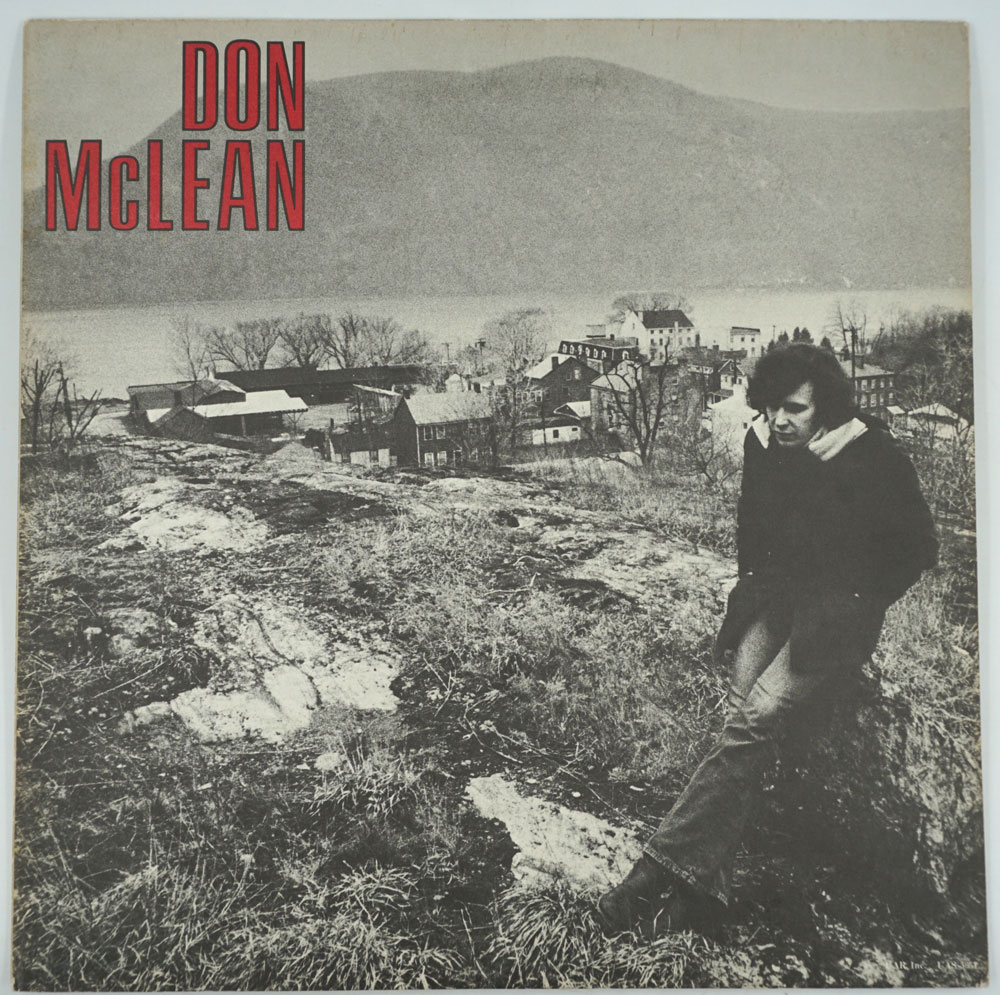

“Dreidel,” Don McLean, 1972

“American Pie” is so imbedded in the arc of popular culture that, sadly, it has overshadowed everything else McLean ever recorded. He is a gifted songwriter who has composed some thoughtful pieces over the years that are worthy of our attention. “Vincent,” his tribute to Van Gogh, was a fairly sizable hit on its own, but other McLean material has been overlooked. I love the changes in tempo and instrumentation that mark the arrangement of “Dreidel,” a modest #21 hit in early 1973 based on the four-sided spinning top Jewish children play with while observing Hanukkah. For him, a dreidel symbolizes life itself: “Round and around the world you go, spinning through the lives of the people you know, we all slow down…”

“Time to Space,” Loggins and Messina, 1974

This duo happened more or less by accident when Jim Messina, a staff producer at Columbia and alumnus of the country rock band Poco, was tasked with shepherding newcomer Kenny Loggins through the production of his debut album. It became instead “Kenny Loggins With Jim Messina Sittin’ In,” the first of six studio albums (plus two live LPs) by the duo in the 1970s. For my money, 1974’s “Mother Lode” is their best stuff, with nary a weak moment on the album. The track that has never ceased to captivate me is “Time to Space,” which begins and ends as a beautiful ballad, interrupted halfway through with an exhilarating uptempo section featuring flute/sax man Jon Clarke. Wow!

“Written in Sand,” Santana, 1985

Emerging from San Francisco at the end of the ’60s, Santana went through many personnel changes over the years, but always with guitar virtuoso Carlos Santana at the helm. The group’s LPs routinely made it to the Top 20 on the US album charts, including two #1s in the early ’70s. The use of congas and vigorous percussion remained a mainstay element of Santana’s oeuvre, but by the 1980s, synthesizers and drum machines began creeping into the mix, which alienated some longtime fans. The 1985 LP “Beyond Appearances” was their first to fail to crack the Top 50, but it had a minor hit, “Say It Again,” featuring vocalist Alex Ligertwood, who also sang on the LP’s best track, the luxurious “Written in Sand.”

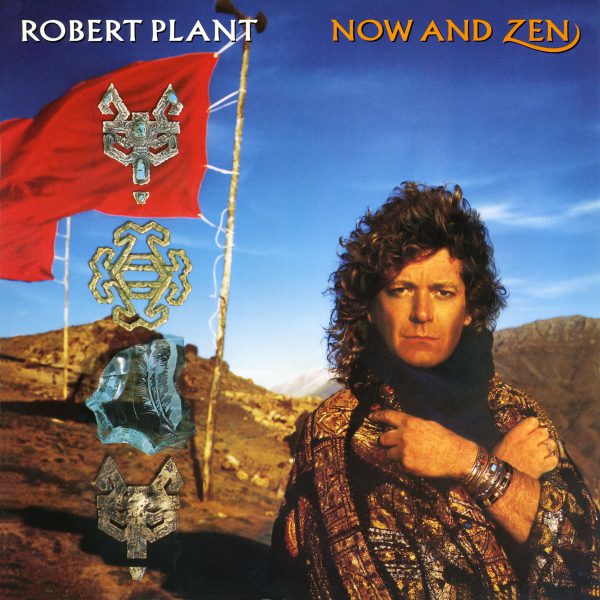

“Ship of Fools,” Robert Plant, 1988

In the wake of Led Zeppelin’s demise, many observers assumed we’d hear much more from Jimmy Page, but it was Robert Plant who emerged with the most active solo career, scoring four consecutive Top 20 LPs in the 1980s. His fourth, “Now and Zen,” was probably his most consistently satisfying, with the killer opening song, “Heaven Knows,” “Helen of Troy” and the intriguing “Tall Cool One,” in which Plant made liberal use of samples from a half-dozen Led Zep tracks. I’m also partial to “Ship of Fools,” a wonderfully moody piece that shows off Plant’s vocal shading in the same way we heard on “I’m in the Mood” from his 1983 LP, “The Principle of Moments.”

“The Right Moment,” Gerry Rafferty, 1982

Following his rocky beginning as half of Stealer’s Wheel, with whom he recorded the 1973 hit “Stuck in the Middle With You,” Rafferty finally resolved legal differences and made a huge splash with his first solo LP, “City to City,” which included the #1 hit “Baker Street” and “Right Down the Line.” Two more albums in the same vein followed, but by 1982, people had stopped paying attention, due in part to Rafferty’s aversion to touring. His “Sleepwalking” album that year failed to chart in the US, but I found three strong songs on it: “Standing at the Gate,” “Cat and Mouse” and the gentle yet forceful “The Right Moment,” carried by Rafferty’s rich vocals and the marvelous keyboard work of Dire Straits’ Alan Clark.

“Bitter Creek,” The Eagles, 1973

With strong personalities like Don Henley and Glenn Frey around, it was inevitable that the other two founding members of The Eagles would eventually feel marginalized enough to become disillusioned and leave the nest. Bernie Leadon, whose country/bluegrass roots had brought him to the group by way of The Flying Burrito Brothers, was probably the group’s most talented player, and a fine vocalist and songwriter as well. He co-wrote three tracks on “Eagles” and then penned two of the best songs on “Desperado” by himself. In particular, Leadon’s “Bitter Creek” remains the most neglected song in The Eagles’ repertoire, with lyrics that warn of desert dangers while tying into the outlaw cowboy theme of the “Desperado” LP.

“Who Knows Where the Time Goes,” Judy Collins, 1968

A stalwart of the thriving folk music scene in Greenwich Village in the early ’60s, Collins at first limited her repertoire to traditional material and the works of Woody Guthrie, Pete Seeger and Bob Dylan. By 1966, she began branching out, attempting covers of nascent songwriters like Joni Mitchell, Gordon Lightfoot, Leonard Cohen and Randy Newman, eventually scoring a Top Ten hit with Mitchell’s “Both Sides Now.” In 1968, she enlisted the help of fine musicians like Stephen Stills, James Burton and pedal steel guitarist Buddy Emmons to beef up the arrangements for her countryish hit, “Someday Soon,” and the moving song written by Fairport Convention’s Sandy Denny, “Who Knows Where the Time Goes.”

*******************************