When I call you up, your line’s engaged

I was listening to an old playlist recently and up popped the 1977 ELO hit “Telephone Line,” which starts with the sound you hear when you’ve placed a call and it’s ringing at the other end of the line. It got me thinking about how ubiquitous the telephone has been in our lives for so many years.

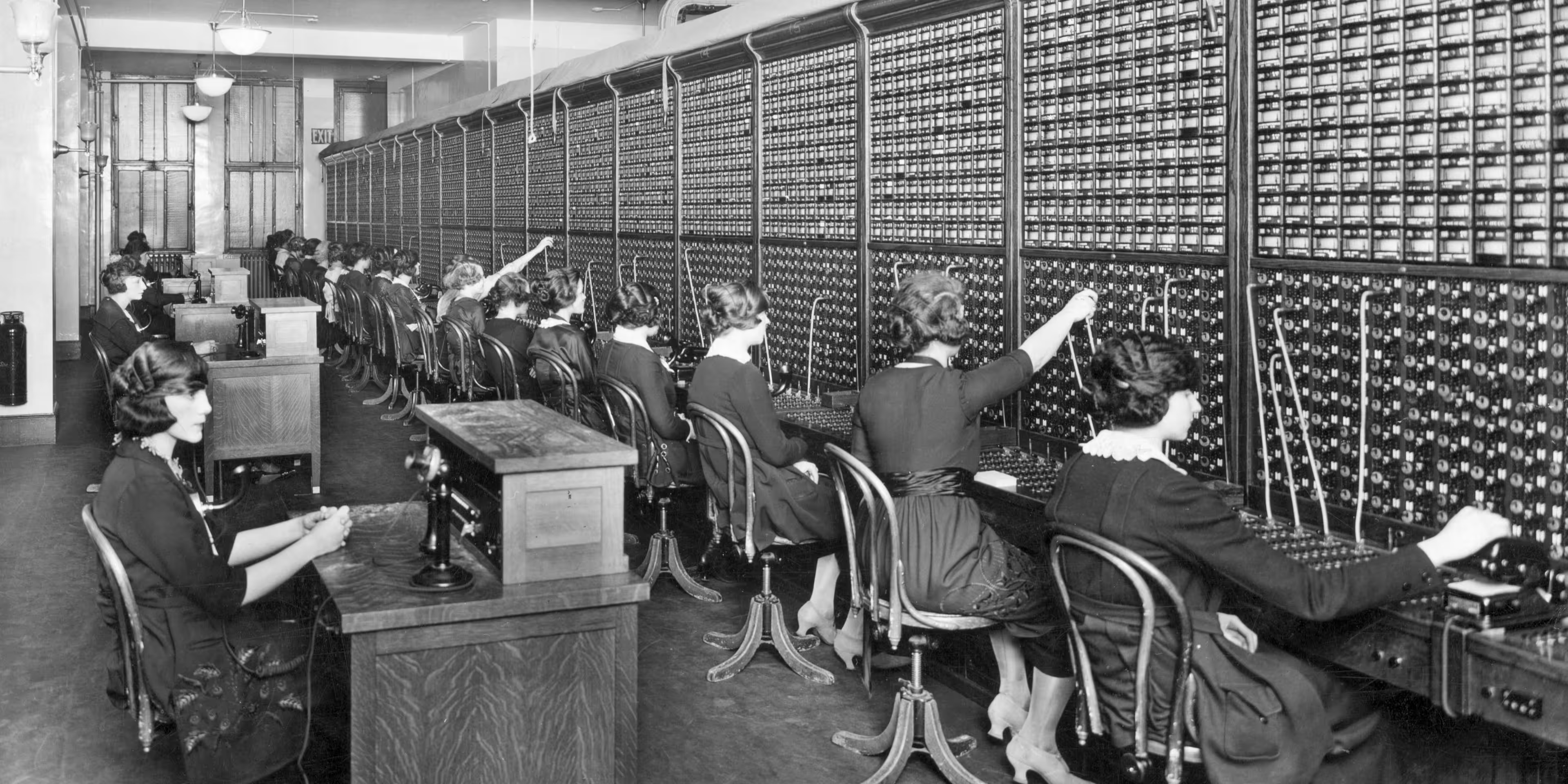

The phone has evolved significantly since the mid-20th Century, when there were such things as shared “party lines,” calls that required “operator assistance,” pay phones everywhere, home phones connected by cords to the kitchen wall, and pricey rates for long-distance calls based on the time of day you’re calling.

These days, of course, those things barely exist, if at all. Most people don’t even have “land lines” anymore. Instead, we have cell phones, where typing texts, taking photos and scrolling have taken precedence over actual conversations.

Remember calling someone and getting a busy signal? Until the “call waiting” feature was introduced in the 1970s, you had to keep trying until you finally got through. And once you got through, sometimes nobody was there and you had to call back later (until the advent of answering machines).

Remember “crank calls,” where you’d phone a random number and play a prank on them? Those went away once the caller could be identified (and maybe prosecuted) thanks to the “*69” and, later, “caller ID” features.

There’s no denying that the phone has been a crucial tool in helping us stay connected, from boys calling girls for dates to maintaining ties with friends who moved to another city. It has also been the focus of classic films (thrillers like “Sorry Wrong Number,” “When a Stranger Calls” and “Dial M For Murder”) and many dozens of popular songs.

A tune like The Turtles’ classic love note “Happy Together” makes brief mention of a phone call (“If I should call you up, invest a dime…”), while The Monkees’ “Last Train to Clarksville” notes the futility of trying to talk on a pay phone in a rowdy location (“Now I must hang up the phone, /I can’t hear you in this noisy railroad station all alone…”). Joni Mitchell’s “You Turn Me On, I’m a Radio” urges a lover to phone her at the radio station (“Dial in the number who’s bound to love you… Call me at the station, the lines are open…”). Some songwriters have created lyrics structured to indicate the whole song is a phone call (Todd Rundgren’s “Hello It’s Me,” Adele’s “Hello”), even though a phone is never specifically mentioned.

I’ve researched the topic and have selected 16 pop/rock songs about telephones from as early as the 1950s to as recently as 2023. There are numerous “honorable mention” listing as well, all included on the Spotify playlist at the end.

*************************

“Operator,” Jim Croce, 1972

This charming, wistful tune is the first one that came to mind as I was thinking of “phone songs.” It’s easily my favorite of Croce’s appealing song catalog, found on his 1972 LP “You Don’t Mess Around With Jim.” In the lyrics, the speaker is trying to find the phone number of his former lover, who has moved to Los Angeles with his former best friend. He is hoping to show both of them that he has survived their betrayal, but admits to the operator that he is in fact not over it. He then changes his mind and tells the operator not to place the call after all. It’s a marvelous melody and vocal performance, and a heartbreaker lyrically that peaked at #17 on US charts: “Give me the number if you can find it, so I can call just to tell ’em I’m fine, /And to show I’ve overcome the blow, I’ve learned to take it well, /I only wish my words could just convince myself that it just wasn’t real, /But that’s not the way it feels…”

“Telephone Line,” Electric Light Orchestra, 1976

When Jeff Lynne, ELO’s leader/songwriter/singer, was assembling tracks for the band’s sixth LP, “A New World Record,” he was aware that the British band’s popularity in the US was growing by leaps and bounds. So when he wanted to include a ring tone as a sound effect for “Telephone Line,” he concluded it needed to be an American ringtone. “We phoned from England to America to a number that we knew nobody would be at, just to listen to that tone for a while, and then we recreated it with a Moog synthesizer.” The song reached #7 in 1977, their second highest charting of 15 Top Twenty hits: “Hello! How are you? /Have you been alright through all those lonely, lonely, lonely, lonely, lonely nights? That’s what I’d say, /I’d tell you everything if you’d pick up that telephone, /Oh, oh, telephone line, give me some time, /I’m living in twilight…”

“Call Me,” Blondie, 1980

Giorgio Moroder, the Italian composer/producer known as the “Father of disco” for pioneering Euro-disco with Donna Summer in the mid-to-late ’70s, wrote the music for this hugely popular track from the “American Gigolo” film soundtrack in 1980. Moroder had approached Stevie Nicks to write lyrics and sing vocals for it, but she declined, and instead, Debbie Harry of Blondie agreed to participate. The lyrics Harry wrote were from the perspective of the lead character, a male prostitute played by Richard Gere, who took his assignments via telephone solicitations. “Call Me” was released in three versions (single, album, and Spanish-language), with the single holding the #1 slot on US pop charts for six weeks: “Call me on the line, Call me, call me anytime, /Call me, oh my love, Call me for a ride, /Call me for some overtime…”

“867-5309/Jenny,” Tommy Tutone, 1982

In the summer of 1981, songwriter Alex Call wanted to write a basic 4-chord rock tune. “I had the guitar lick, and I had the name and phone number, but I didn’t know yet what the song would be about. My friend Jim Keller, guitarist for Tommy Tutone, stopped by, heard it and said, ‘Well, it could be a girl’s phone number on a bathroom wall.’ We had a good laugh, and I said, ‘That’s exactly right, that’s what it should be!’ He and I wrote the verses in about 15 minutes.” Tommy Tutone recorded it and took it to #4 on US pop charts in 1982. From coast to coast, there were multiple instances of annoyed people with the 867-5309 phone number who were continually pestered with prank calls, and a few of them were even named Jenny! “If I ever met the guy who wrote it, I’d punch him in the face,” said one: “I know you think I’m like the others before who saw your name and number on the wall, /Jenny, I got your number, I need to make you mine, /Jenny, don’t change your number, 867-5309…”

“All I’ve Gotta Do,” The Beatles, 1963

“That was me trying to imitate Smokey Robinson,” said John Lennon about this tune from the “With the Beatles” LP in 1963. He said he wrote it specifically with the American market in mind, because the idea of calling a girl on the telephone was unthinkable to a British youth in the early 1960s. “I loved the idea of merely picking up the phone in order to talk to a girl. That seemed fantastic to me, because phones weren’t part of an English child’s life at that point. I had never called a girl on the phone in my life, but in America, it happened all the time.” “And when I wanna kiss you, yeah, /All I gotta do is call you on the phone, and you’ll come running home, /Yeah, that’s all I gotta do, /And the same goes for me, whenever you want me at all, /I’ll be here, yes I will, whenever you call, /You just gotta call on me…”

“Rikki Don’t Lose That Number,” Steely Dan, 1974

So many of the songs Donald Fagan and Walter Becker wrote for the Steely Dan records offered cryptic lyrics open to different interpretations. Some stoners thought “Rikki Don’t Lose That Number” referred to a joint the speaker had given to the woman, but Fagen dispelled that rumor. “I’d had a crush on a woman named Rikki, a professional writer who was married to one of my college professors. I slipped her my phone number as she was leaving the country in the hopes she would be flattered enough to call me, but she never did.” Years later, the woman said she was stunned when she heard her name in the lyrics of the song on the radio, where it reached #4 on US pop charts in 1974. “Rikki ,don’t lose that number, /You don’t wanna call nobody else, /Send it off in a letter to yourself, /Rikki, don’t lose that number, It’s the only one you own, /You might use it if you feel better when you get home…”

“Telephone Song,” The Vaughan Brothers, 1990

Stevie Ray Vaughan emerged from Austin, Texas in the early ’80s as the hot new stud on the blues guitar, and was credited with bringing blues music back into vogue commercially. Concurrently, Vaughan’s older. brother Jimmie had been a key figure in The Fabulous Thunderbirds, who also achieved some chart success in the late ’80s. In 1990, the Vaughan brothers pooled their talents for one LP, “Family Style,” which was released one month following the tragic death of Stevie Ray in a helicopter crash that year. It reached #7 on US album charts, and included memorable original blues tunes like “Telephone Song,” which Stevie Ray co-wrote and sang: “Woke up this morning, I was all alone, /Saw your picture by the telephone, I was missing you so bad, /Wish I had you here to hold, all I’ve got is this touch telephone, /Guess I’ll have to give you a call…”

“Beechwood 4-5789,” The Marvelettes, 1962

Co-written by Marvin Gaye and Mickey Stevenson, this frothy Motown tune was a modest hit in 1962 for the “girl group” The Marvelettes, reaching #17 on pop charts. Its anachronistic title refers to the then-standard use of telephone exchange names like Beechwood, Yellowstone, Skyline and Sweetbriar, with the first two letters of the exchange name substituting for digits. It sounds pretty dated today, but it was the first pop song to use a phone number in the title and lyrics. The song was covered 20 years later by The Carpenters as one of the duo’s final singles before Karen Carpenter’s premature death in 1982. “I’ve been waiting, standing here so patiently for you to come over and have this dance with me, /And my number is Beechwood 4-5789, you can call me up and have a date any old time…”

“Switchboard Susan,” Nick Lowe, 1979

In 1978, veteran British guitarist/songwriter Mickey Jupp was working on a comeback album with two different backing bands on various tracks. One was Lowe’s band Rockpile, who helped him record a great rocker called “Switchboard Susan,” but Jupp was so unhappy with it that he sent Lowe on his way, saying, “And take that song with you. I don’t want it anymore.” Lowe and Rockpile chose to include the track (with a new vocal overdub by Lowe) on his 1979 LP “Labour of Lust,” which included the hit single “Cruel To Be Kind.” “Switchboard Susan” flopped as a follow-up single despite creatively suggestive lyrics about the singer’s infatuation with a telephone operator: “Switchboard Susan, won’t you give me a line? /I need a doctor, give me 999, /First time I picked up the telephone, /I fell in love with your ringing tone, /I’m a long distance romancer, /I keep on trying till I get an answer… /When I’m near you, girl, I get an extension, /And I don’t mean Alexander Graham Bell’s invention…”

“Don’t Call Us, We’ll Call You,” Sugarloaf, 1974

In 1970, the Denver-based group Sugarloaf had a #3 hit with the catchy “Green-Eyed Lady,” but it took them four years to come up with a follow-up hit. Lead singer Jerry Corbett wrote lyrics which describe the difficulty of breaking into the music business and securing a contract from the record company, who claims that the band is good, but too derivative of other popular bands at the time. Said Corbetta, “Bands get that kind of response all the time — ‘don’t call us, we’ll call you’ — and I thought it would make a great song, and a great title.” Sure enough, it became a #9 hit on US charts in late 1974, using the sound of a touch-tone phone entering a number: “He said ‘hello’ and put me on hold, /To say the least, the cat was cold, /He said, ‘Don’t call us, child, we’ll call you’…”

“Memphis,” Johnny Rivers, 1964

Chuck Berry wrote this basic early rocker in 1959, then entitled “Memphis, Tennessee,” and several other artists shortened the title to “Memphis” and covered it in later years, including The Beatles (found on their “Live at the BBC” album), and especially Rivers, whose version peaked at #2 in 1964. The lyrics hark back to a time when we could call “long distance information” to learn a phone number and be connected to it. If you listen closely, you’ll see that the girl (named Marie) that the caller is trying to reach from many miles away is not his lover or ex-wife, but his six-year-old daughter: “Help me, information, more than that, I cannot add, /Only that I miss her and all the fun we had, /Marie is only six years old, information, please, /Try to put me through to her in Memphis, Tennessee…”

“Call Me Maybe,” Carly Rae Jepsen, 2012

In her early 20s, Jepsen turned heads with stirring performances on “Canadian Idol,” the Canadian edition of the popular US TV program. By 2012, she became an international sensation with “Call Me Maybe,” which reached #1 in more than a dozen countries. Interestingly, it was written as a folk song, “but when we hit the studio to record it, the producer urged us to ‘popify’ it,” Jepsen said. The lyrics describe the feeling of “infatuation and the inconvenience of love at first sight,” as one critic put it. “It’s an eyelash-fluttering flirtation, a perfect summer pop song that straddles the line between irresistible and sickly sweet.” Said Jepsen, “It’s basically a pick up. What person hasn’t wanted to approach somebody but hesitated because it’s scary? So you slip them your phone number.” “Hey, I just met you, and this is crazy, /But here’s my number, so call me, maybe? /It’s hard to look right at you, baby, /But here’s my number, so call me, maybe?…”

“Star 69,” R.E.M., 1993

Following the runaway success of the pop-oriented “Automatic For the People” album in 1992, R.E.M. did an about-face and embraced a harder-edged approach for their “Monster” follow-up LP in 1993, which featured the single “What’s the Frequency, Kenneth?” One of the more popular tracks was the glam punk anthem “Star 69,” whose title refers to the access number for the last-call return feature of North American telephones. The lyrics offer a tale of mysterious celebrity obsession, kind of a rough cousin of “Pop Song 89” from their breakthrough “Green” LP. “Three people have my number, the other two were with me, /I don’t like to tell, but i’m not your patsy, /This time, you have gone too far with me, I know you called, I know you called, I know you hung up my line, star 69…”

“If the Phone Doesn’t Ring, It’s Me,” Jimmy Buffett, 1985

Buffett was famous for writing light-hearted, whimsical songs with lyrics that poke fun at our foibles. Titles like “Weather is Here, Wish You Were Beautiful,” “Off to See the Lizard” and “We are the People Our Parents Warned Us About” are great examples of his clever wordplay. There’s some disagreement as to whether he coined the phrase “If the Phone Doesn’t Ring, It’s Me” — it appears in a few country songs in various forms — but regardless of its origin, it’s a marvelous way of telling someone you’re moving on and won’t be calling anymore. The song appears as a deep album track on Buffett’s 1985 LP “Last Mango in Paris” (more amusing wordplay there)… “If the phone doesn’t ring, you know that I’ll be where someone can make me feel warm, /It’s too bad we can’t turn and live in the past, /If the phone doesn’t ring, it’s me…”

“634-5789,” Wilson Pickett, 1966

Singer/songwriter Eddie Floyd and guitarist/songwriter Steve Cropper were both major behind-the- scenes figures at Stax Records in Memphis, oner of the important hotbeds of soul music in the 1960s (along with Detroit). Floyd had his own hit with “Knock on Wood,” while Cropper was the de facto leader of the Stax house bands on dozens of hit singles. They teamed up to write “634-5789″ for Wilson Pickett,” who turned it into a #13 hit on pop charts in 1966 (and #1 on R&B charts). The song is a direct nod to The Marvelettes’ earlier hit “Beechwood 4-5789” (see above), with lyrics that repeat the “call me and I’ll come right over” theme, but with a far grittier and authentic soul style: “No more lonely nights when you’ll be alone, /All you gotta do is pick up your telephone and dial now, 634-5789, that’s my number! /Oh, I’ll be right there, just as soon as I can…”

“She Calls Me Back,” Noah Kahan with Kacey Musgraves, 2023

Kahan has become wildly popular on the strength of his excellent 2022 LP “Stick Season,” full of great songs he wrote while holed up in Vermont during the COVIN pandemic. Said Kahan, “‘She Calls Me Back’ is about calling somebody, knowing that the relationship is ending, but still hanging on to it by the skin of its teeth. The narrator is bitter at being left but angry at himself for still needing to keep calling.” In 2023, Kahan recorded new versions of several tracks in duets with other artists, including “She Calls Me Back” with Musgraves, who wrote and sang a new verse that moves the lyrics forward. “It’s the other person on the phone being like, ‘Hey, I’m moving on.’ It offers the other side, which allows the song to move into a place of resolve instead of this bitter tension that exists in the original.” Kahan: “Lost for a long time, two parallel lines, /Everything’s alright when she calls me back…” Musgrave: “If you think that you could wake me up, then you don’t know how well I sleep, /You love me and I don’t know why, I only call you once a week…”

************************

Honorable mentions:

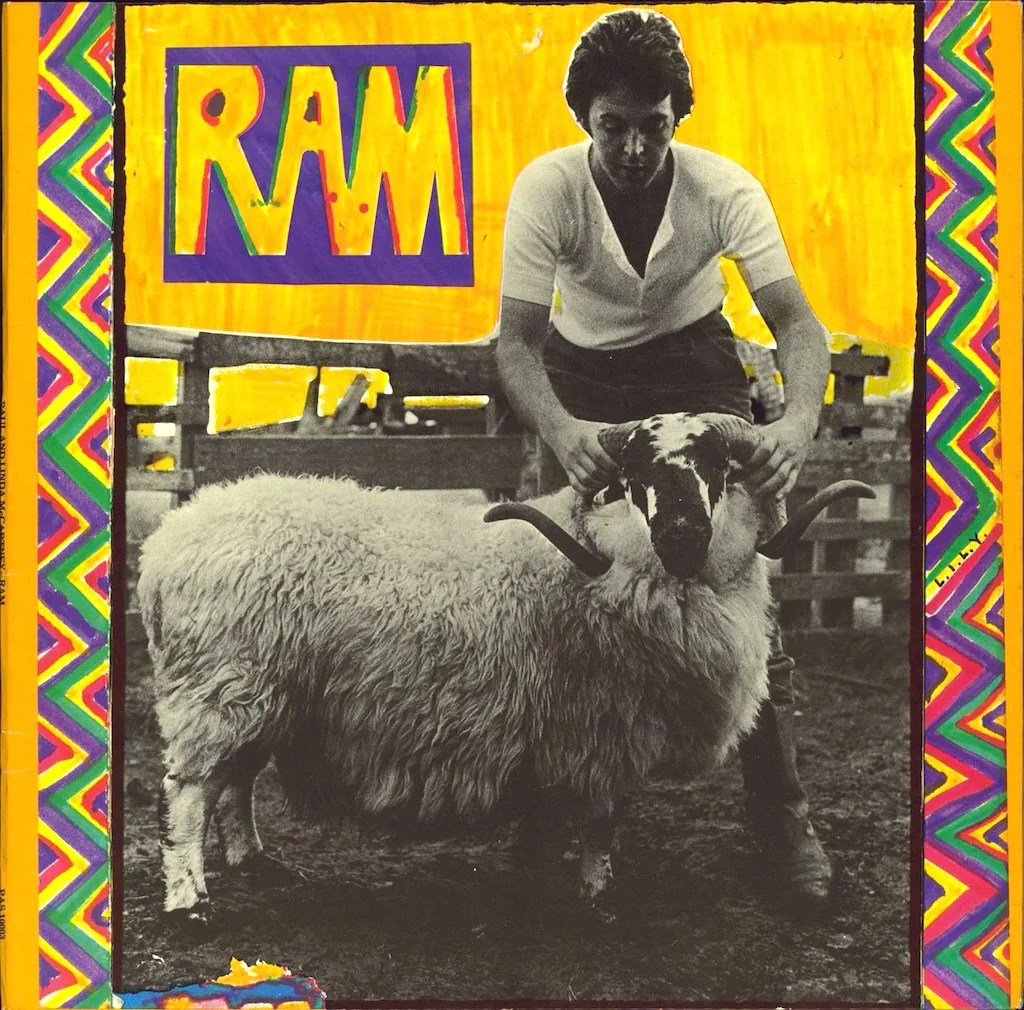

“Telefone (Long Distance Love Affair),” Sheena Easton, 1983; “Call Me,” Chris Montez, 1966; “Answering Machine,” The Replacements, 1984; “Man On the Line,” Chris DeBurgh, 1984; “Off the Hook,” The Rolling Stones, 1965; “Don’t Lose My Number,” Phil Collins, 1985; “Telephone,” Lady Gaga with Beyoncé, 2009; “Hello It’s Me,” Todd Rundgren, 1972; “Hello,” Adele, 2015; “Call Me Back Again,” Paul McCartney and Wings, 1975; “The Telephone Always Rings,” Fun Boy Three, 1982; “The Phone Call,” The Pretenders, 1980; “Hanging on the Telephone,” Blondie, 1978; “Call Me Back,” The Strokes, 2011; “I Just Called to Say I Love You,” Stevie Wonder, 1984.

*************************