I try to recall the words you used to sing to me

I long ago concluded that I’m among the minority of people that have a great capacity for remembering song lyrics, particularly from tunes of the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s.

If we’re talking about big hit singles, perhaps most people can sing along or recognize the words from the printed page. Fewer folks can identify the title or artist responsible for deeper album tracks.

In this ’60s/’70s/’80s lyrics quiz I’ve assembled, you’ll find a cross section of the classic rock hits and the more obscure numbers from decades past, presented here to challenge your abilities at identifying them. I invite you to ruminate on the lyrics, jot down your best guesses, and then scroll down to see how well you did. There’s a Spotify playlist at the end to listen to the songs anew as you celebrate or bemoan how you did.

Enjoy.

*****************************

1 “I’ve been thinking ’bout our fortune, and I’ve decided that we’re really not to blame, for the love that’s deep inside us now is still the same…”

2 “Sometimes it’s like someone took a knife, baby, edgy and dull, and cut a six-inch valley through the middle of my skull…”

3 “She lit a burner on the stove and offered me a pipe, ‘I thought you’d never say hello,’ she said, ‘You look like the silent type’…”

4 “Tom, get your plane right time, I know that you’ve been eager to fly now, hey, let your honesty shine, shine shine now…”

5 “Go away then, damn ya, go on and do as you please, you ain’t gonna see me getting down on my knees…”

6 “Well, I hear the whistle but I can’t go, I’m gonna take her down to Mexico, she said, ‘Whoa no, Guadalajara won’t do’…”

7 “Grab your lunch pail, check for mail in your slot, you won’t get your check if you don’t punch the clock…”

8 “I said, ‘Wait a minute, Chester, you know I’m a peaceful man,’ he said, ‘That’s okay, boy, won’t you feed him when you can?’…”

9 “It’s gonna take a lot to drag me away from you, there’s nothing that a hundred men or more could ever do…”

10 “I’m gonna be a happy idiot and struggle for the legal tender…”

11 “I can remember the Fourth of July, running through the back woods bare…”

12 “Sitting by the fire, the radio just played a little classical music for you kids, the march of the wooden soldiers…”

13 “I got my back against the record machine, I ain’t the worst that you’ve seen, oh can’t you see what I mean?…”

14 “Got to have a Jones for this, Jones for that, this runnin’ with the Joneses, boy, just ain’t where it’s at…”

15 “Come down off your throne and leave your body alone, somebody must change…”

16 “I’m not the only soul who’s accused of hit and run, tire tracks all across your back, I can see you had your fun…”

17 “Well, there’s a rose in a fisted glove, and the eagle flies with the dove…”

18 “There’s too many men, too many people making too many problems, and not much love to go ’round…”

19 “I’ve acted out my love in stages with ten thousand people watching…”

20 “Jump up, look around, find yourself some fun, no sense in sitting there hating everyone…”

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

ANSWERS:

1 “I’ve been thinking ’bout our fortune, and I’ve decided that we’re really not to blame, for the love that’s deep inside us now is still the same…”

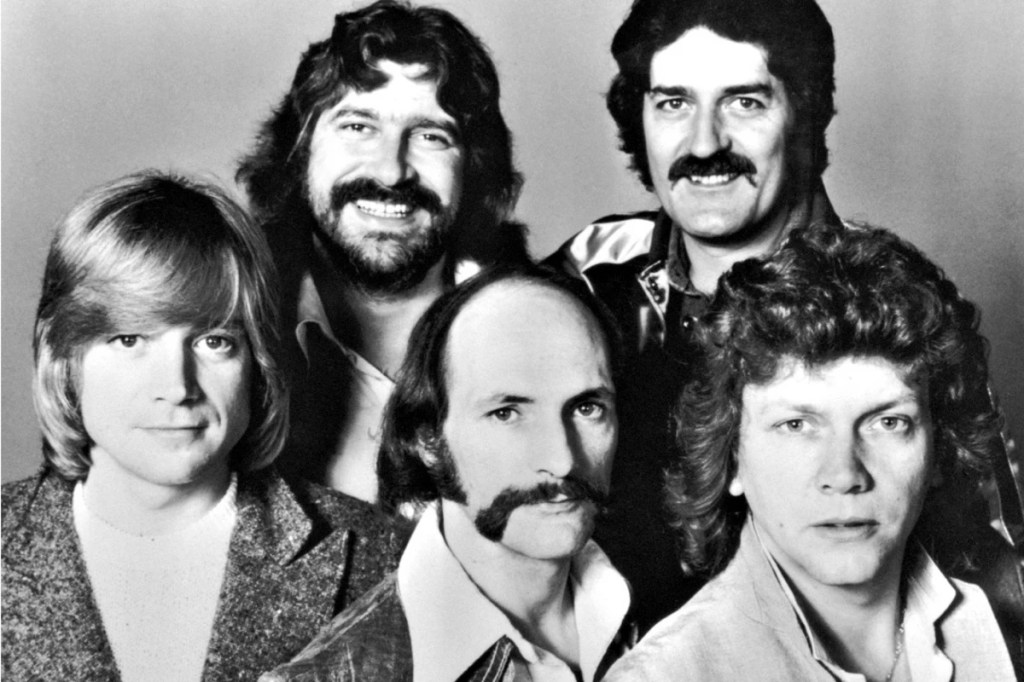

“The Story in Your Eyes,” The Moody Blues (1971)

These guys have had at least three lives: their early “Go Now” period; their stunning 1967-1972 era, and a rebirth in 1981 for another run in the Eighties. There are so many fine songs in their repertoire, most of them written by singer-guitarist Justin Hayward. My personal favorite is “The Story in Your Eyes,” an infectious track from their “Every Good Boy Deserves Favour” album.

2 “Sometimes it’s like someone took a knife, baby, edgy and dull, and cut a six-inch valley through the middle of my skull…”

“I’m on Fire,” Bruce Springsteen (1984)

On the multiplatinum “Born in the U.S.A.” album, Springsteen assembled a dozen songs he’d chosen from nearly four dozen he wrote and recorded with the E Street Band. This track was unique in its use of spare percussion with synthesizer, and lyrics that describe the narrator’s sexual tension and longing. The song reached #6 in 1985, one of an unprecedented seven Top Ten singles from the same LP.

3 “She lit a burner on the stove and offered me a pipe, ‘I thought you’d never say hello,’ she said, ‘You look like the silent type’…”

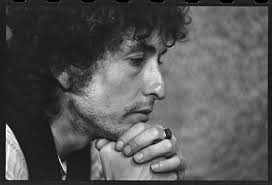

“Tangled Up in Blue,” Bob Dylan (1975)

Many critics regard Dylan’s “Blood on the Tracks” as one of his top three or four in a catalog of well over 50 albums in his career. Part of the reason is this incredible song, which offers some of his best lyrics as he tells the story of a man’s recollections about his old flame, and his travels to try to find and reconnect with her. Dylan himself has cited this song as one of his best compositions.

4 “Tom, get your plane right time, I know that you’ve been eager to fly now, hey, let your honesty shine, shine shine now…”

“The Only Living Boy in New York,” Simon and Garfunkel (1970)

Art Garfunkel had been picked for a role in the film “Catch-22,” which kept him on the Mexico movie set for nearly six months. Meanwhile, Paul Simon was in New York writing songs and trying to complete the duo’s next album. He felt lonely and a bit resentful, and this song came out of that feeling. It’s one of my favorite S&G songs, with a crystal-clean production and outstanding vocals.

5 “Go away then, damn ya, go on and do as you please, you ain’t gonna see me getting down on my knees…”

“Don’t Let Me Be Lonely Tonight,” James Taylor (1972)

For his “One Man Dog” album, released in December 1972, Taylor put together 18 songs, some barely a minute long, with seven of them assembled in an “Abbey Road”-like medley. He recorded some of the LP in his new home studio on Martha’s Vineyard, with new bride Carly Simon contributing background vocals. “Don’t Let Me Be Lonely Tonight” was the single, which peaked at #14 in early 1973.

6 “Well, I hear the whistle but I can’t go, I’m gonna take her down to Mexico, she said, ‘Whoa no, Guadalajara won’t do’…”

“My Old School,” Steely Dan (1973)

Donald Fagen and Walter Becker met at Bard College in upstate New York, where the formed their lasting musical partnership, but they didn’t much care for the time they spent there. In this song, they wrote about their unpleasant experiences and made their feelings quite clear with the chorus lyric, “And I’m never going back to my old school!” It’s one of Steely Dan’s best tunes, from their “Countdown to Ecstasy” LP.

7 “Grab your lunch pail, check for mail in your slot, you won’t get your check if you don’t punch the clock…”

“Bus Rider,” The Guess Who (1970)

I always loved this minor hit from the Guess Who repertoire. Written by Kurt Winter, the guitarist who replaced Randy Bachman in the band’s lineup, it gallops along on the strength of Burton Cummings rollicking piano and strong vocals. Winter had been a daily bus commuter when he worked a day job and thought the experience would be a good topic for a song. He was right.

8 “I said, ‘Wait a minute, Chester, you know I’m a peaceful man,’ he said, ‘That’s okay, boy, won’t you feed him when you can?’…”

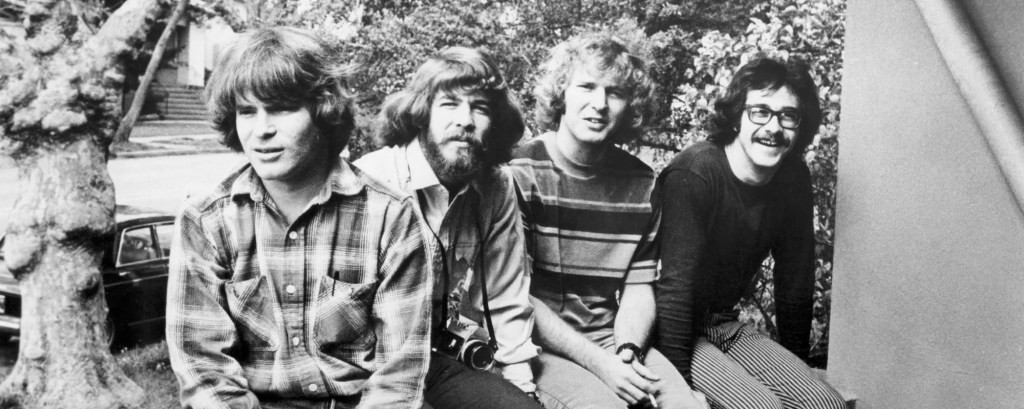

“The Weight,” The Band (1968)

Although it was released as a single which never reached higher than #63 on the charts, “The Weight” significantly influenced American popular music. It was ranked an impressive #41 on Rolling Stone’s Best 500 Songs of All Time. It’s essentially a Southern folk song, with elements of country and gospel, and Robbie Robertson said he wrote it during his first visit to Memphis, where singer Levon Helm had grown up.

9 “It’s gonna take a lot to drag me away from you, there’s nothing that a hundred men or more could ever do…”

“Africa,” Toto (1982)

Chief songwriter David Paich wrote this lyrical tribute to The Dark Continent without ever having visited it. “I saw a National Geographic special on TV and it affected me profoundly,” said Paich. The resulting track, fleshed out with some searing guitar work by guitarist Steve Lukather, turned out to be Toto’s only #1 hit, although it was “Rosanna” that won Grammys.

10 “I’m gonna be a happy idiot and struggle for the legal tender…”

“The Pretender,” Jackson Browne (1976)

When asked who “the pretender” was, Browne said, “It’s anybody that’s lost sight of some of their dreams and is going through the motions, trying to make a stab at a certain way of life that he sees other people succeeding at.” As the title track of his fourth album, the song anchors a strong batch of tunes he wrote in the wake of his wife’s suicide, which share a mid-Seventies resignation to the fact that the Sixties idealism was long gone.

11 “I can remember the Fourth of July, running through the back woods bare…”

“Born on the Bayou,” Creedence Clearwater Revival (1969)

I’ve always considered this song the definitive CCR track. The wonderfully swampy groove, John Fogerty’s vocal growl and biting guitar solo, plus lyrics that take the listener deep into Louisiana, bring all the band’s key elements together in one great recording. The group’s “Bayou Country” and “Green River” LPs should both be minted in gold. Every song shines.

12 “Sitting by the fire, the radio just played a little classical music for you kids, the march of the wooden soldiers…”

“Sweet Jane,” The Velvet Underground (1970)

This great tune by Lou Reed had plenty of airplay on FM rock stations, both in its multiple recordings by Reed’s band The Velvet Underground and by Reed as a solo artist. The 10-minute version on Reed’s 1978 live album “Take No Prisoners” is my favorite, but probably the best known version is by Mott the Hoople from their 1972 album, “All the Young Dudes.”

13 “I got my back against the record machine, I ain’t the worst that you’ve seen, oh can’t you see what I mean?…”

“Jump,” Van Halen (1984)

Instead of the guitar-driven sound that dominates the band’s catalog, the melody of “Jump” is carried by a synthesizer, which was much in vogue in the mid-’80s. David Lee Roth has said the lyrics were inspired by a news story about a man threatening to jump from a tall building and how “there was probably at least one person in the crowd that mumbled, ‘Oh, go ahead and jump.'” It was a big #1 hit from their “1984” album.

14 “Got to have a Jones for this, Jones for that, this runnin’ with the Joneses, boy, just ain’t where it’s at…”

“Lowdown,” Boz Scaggs (1976)

Scaggs had been in the original Sixties lineup of the Steve Miller Band before going solo in 1969. He fashioned an unusual mixture of country, blues and R&B in his music, which attracted a cult audience but didn’t click with the mainstream until 1976 when he released the superb “Silk Degrees” album. His supporting cast included the top-notch session men who would later form Toto. “Lowdown” reached #6 on the charts that year.

15 “Come down off your throne and leave your body alone, somebody must change…”

“Can’t Find My Way Home,” Blind Faith (1969)

Steve Winwood, on hiatus from his band Traffic, teamed up briefly with Eric Clapton and Ginger Baker for one album and a brief tour before disbanding. Winwoods’s influence is strong on all six tunes on the record, but none more so than the acoustic gem “Can’t Find My Way Home.” It would have fit perfectly on the subsequent “John Barleycorn” album, and in fact, many people have always presumed it’s a Traffic song.

16 “I’m not the only soul who’s accused of hit and run, tire tracks all across your back, I can see you had your fun…”

“Crosstown Traffic,” Jimi Hendrix Experience (1968)

By the time of his third album, the sprawling double LP “Electric Ladyland,” Hendrix was experimenting more with different musicians brought in to work on individual tracks. This song, though, features just the original trio as they power their way through a classic Hendrix blues/rock arrangement. The lyrics compare a challenging relationship to the chaos of a Manhattan traffic jam.

17 “Well, there’s a rose in a fisted glove, and the eagle flies with the dove…”

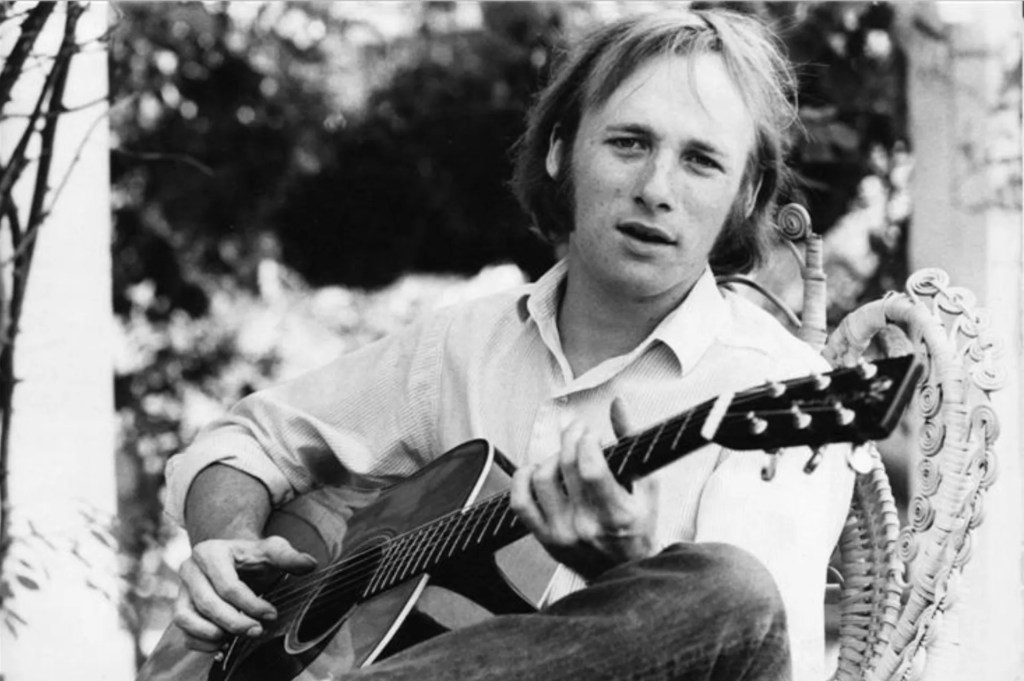

“Love the One You’re With,” Stephen Stills (1970)

If you think this tune is from the Crosby, Stills and Nash catalog, you’re not far wrong. Technically, it’s from Stephen Stills’s debut solo album, not a CSN album, but it pretty much qualifies as a group production because Crosby and Nash were both at the recording session singing background vocals. Stills borrowed the title from a line he heard Billy Preston say one night while on tour.

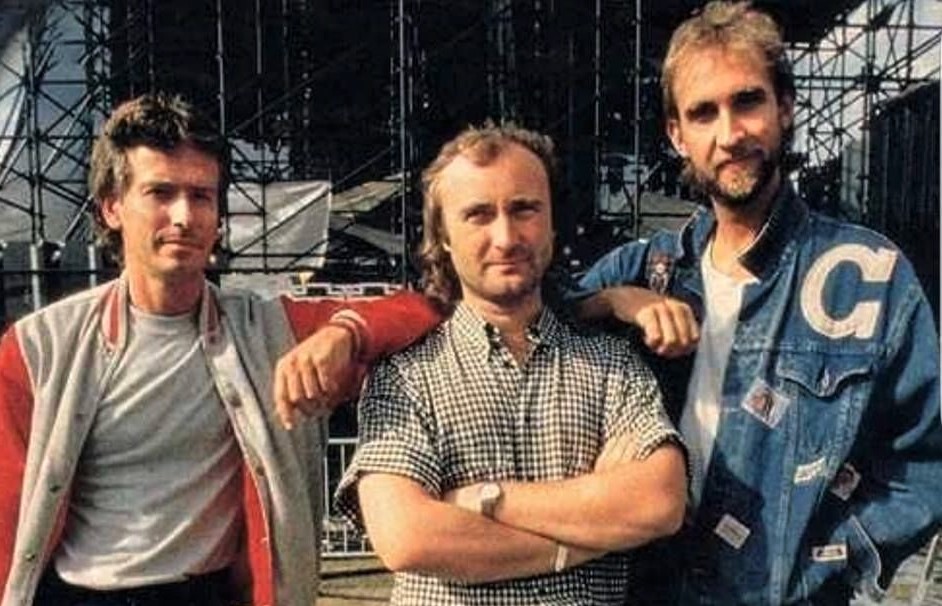

18 “There’s too many men, too many people making too many problems, and not much love to go ’round…”

“Land of Confusion,” Genesis (1986)

Between Genesis albums and solo records, Phil Collins’s voice seemed to be on the radio every 30 minutes for a while in the mid-’80s. The Genesis LP “Invisible Touch” sold a zillion copies on the strength of tracks like “Tonight, Tonight, Tonight,” the title song and this strong tune. Although written more than 30 years ago, “Land of Confusion” seems like an apt description of the United States in the age of coronavirus.

19 “I’ve acted out my love in stages with ten thousand people watching…”

“A Song For You,” Leon Russell (1970)

Russell not only spent many years as a member of the group of L.A. studio musicians known as The Wrecking Crew, he also wrote some iconic songs along the way. The two that stand out for me are “This Masquerade” and “A Song for You,” both of which were eventually recorded by The Carpenters, George Benson and others. Russell’s distinctive voice makes his own recording of “A Song for You” particularly memorable.

20 “Jump up, look around, find yourself some fun, no sense in sitting there hating everyone…”

“Teacher,” Jethro Tull (1970)

This song, one of the anchors of Tull’s third album, “Benefit,” didn’t appear on the British version but was instead released as a single there. It stiffed on the charts, but in the US it became very popular on FM rock stations, thanks to the catchy rock arrangement carried by Anderson’s distinctive flute and the first appearance of John Evan’s swirling organ passages.

**********************************