Play me a song that I’ll always remember

Although I enjoy discovering new artists and new releases, diving into the albums of the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s is still one of my favorite pasttimes. There was SO MUCH great music made in those decades, and I love unearthing the deeper tracks, the “lost classics,” to give them exposure to my Hack’s Back Pages audience.

Readers tell me they love these forays into our collective past, so I hope you enjoy this week’s batch. As is customary, there’s a Spotify playlist at the end so you can listen as you read.

Rock on, music lovers!

************************

“Dance on a Volcano,” Genesis, 1976

In 1975, when Genesis vocalist/frontman Peter Gabriel announced he was leaving at the end of the band’s “The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway” tour, many observers figured it would be the end of the group. Gabriel’s distinctive voice and mesmerizing stage presence were arguably the most important elements of the band’s success. Granted, keyboardist Tony Banks, guitarist Steve Hackett, bassist Mike Rutherford and drummer Phil Collins were all superb musicians who contributed mightily to the songwriting and arrangements… but who would sing? As the story goes, they apparently auditioned nearly 200 vocalists (!) before they found the answer right in their own back yard. Phil Collins, it turned out, had the uncanny ability to sound a lot like Gabriel, especially in the studio, where they came up with an astounding transitional LP, “A Trick of the Tail,” featuring eight songs of fantasy/progressive rock much like the stuff they’d been churning out with Gabriel. The excellent opening track, “Dance on a Volcano,” is perhaps the best example of this Genesis 2.0 model, which had a shelf life of about five years before a much more commercially oriented Genesis 3.0 version evolved around 1980.

“Out in the Country,” Three Dog Night, 1970

Perhaps my favorite song from the Three Dog Night catalog is this pretty piece from their “It Ain’t Easy” LP in the fall of 1970. This group was famous for recording tunes written by other notable composers, from Harry Nilsson (“One”) and Randy Newman (“Mama Told Me Not to Come”) to Laura Nyro (“Eli’s Comin'”) and Hoyt Axton (“Joy to the World”). “Out in the Country,” which reached #15 on the singles chart, was no exception — it was written by Paul Williams and Roger Nichols, known for white-bread commercial fare like The Carpenters’ hits “We’ve Only Just Begun” and “Rainy Days and Mondays,” as well as another 3DN song, “Just an Old Fashioned Love Song.” The track was the group’s only hit that featured unison vocals instead of featuring one lead vocalist. Its lyrics, which cry for concern for the environment, are every bit as relevant today as we continue to face threats to the planet’s future: “Before the breathing air is gone, before the sun is just a bright spot on the nighttime…”

“Rehumanize Yourself,” Police, 1981

Slickly produced and full of diverse, engaging songs, The Police’s “Ghost in the Machine” continued the British band’s musical evolution as one of the top artists of the early Eighties. The group maintained the foothold in punk and reggae they’d been featuring since their 1978 debut, but this album was more New Wave, introducing synthesizers and even horns to the mix. Hits included the catchy “Every Little Thing She Does is Magic” and “Spirits in the Material World,” but just as intriguing were deep tracks like “Secret Journey,” “Darkness, “One World” and my favorite, the uptempo “Rehumanize Yourself.” They would go on to rule the airwaves and the charts two years later with their final LP, “Synchronicity,” before songwriter/singer Sting headed out for a long solo career.

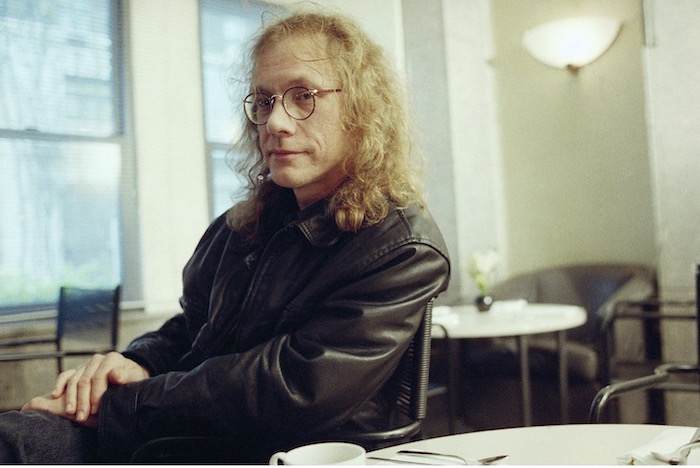

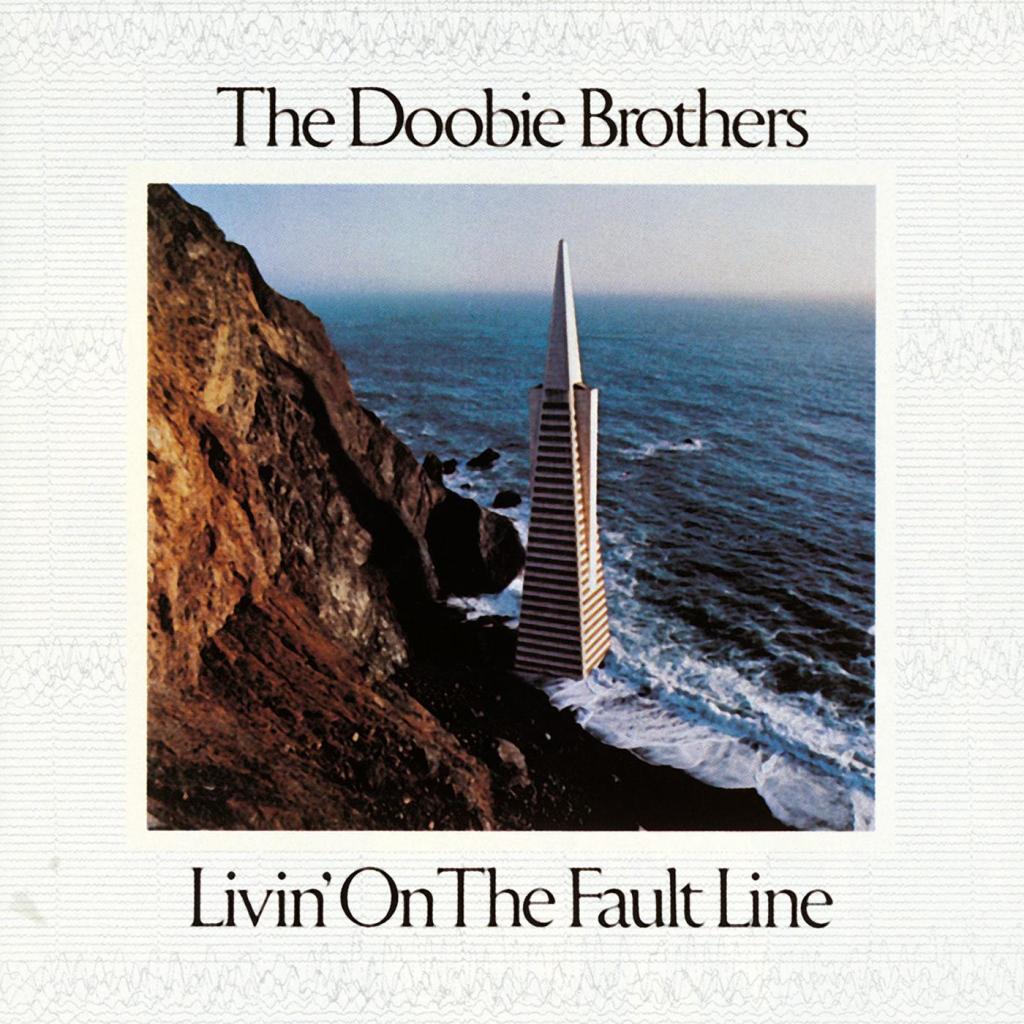

“Echoes of Love,” Doobie Brothers, 1977

In 1976, medical conditions caused singer-guitarist-songwriter Tom Johnston to withdraw from the band he had formed six years earlier. To replace him (temporarily), the Doobies recruited Steely Dan background vocalist Michael McDonald, who turned out to be a pretty decent songwriter as well, although his stuff was markedly different from Johnston’s rock ‘n roll boogie. The Doobies began a new phase in their career with “Takin’ It to the Streets,” a solid album with one Johnston song amidst a half dozen McDonald-led numbers. Throughout all of this, there was always another vital piece of the band’s sound: singer-songwriter-guitarist Patrick Simmons, who had been responsible for tunes like “Black Water,” “South City Midnight Lady,” “Toulouse Street” and others. On the 1977 LP “Livin’ on the Fault Line,” Simmons shines brightly on his outstanding song “Echoes of Love,” with McDonald on harmonies and the venerable California band sounding as tight as ever.

“Car on a Hill,” Joni Mitchell, 1974

What a marvelous track from a perfect album! Together with the live “Miles of Aisles” LP that followed it, “Court and Spark” was Mitchell’s high-water mark commercially — both albums went Top Five — but she soon tired of “stoking the star-maker machinery behind the popular song” and began writing and recording with top-flight jazz artists through the rest of the ’70s. Joni is one of only a handful of songwriters whose lyrics and music are of equally fine caliber. In particular, “Car on a Hill” has a fabulous melody and arrangement, and the words do a beautiful job of describing the angst of waiting by the window for the unfaithful lover’s car that never comes: “He said he’d be over three hours ago… Now where in the city can that boy be?, waitin’ for a car, climbin’, climbin’, climbin’ the hill…”

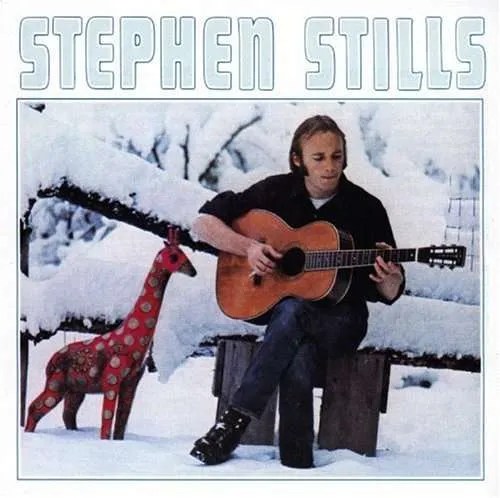

“Go Back Home,” Stephen Stills (with Eric Clapton), 1970

After the implosion of Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young in the summer of 1970, each went off to make solo LPs, although they made guest appearances on each others’ albums. Stephen Stills had headed to London to record with a broad array of musicians, including the legendary Jimi Hendrix, who added guitar on “Old Times Good Times” only a month before his death. More impressive, however, was the contribution from Eric Clapton, who offered up a scorching performance on the second half of Stills’ mid-tempo shuffle “Go Back Home,” arguably one of Clapton’s best guest solos. (It was recorded at the same session that produced “Let It Rain” and “After Midnight” for Clapton’s solo debut LP that same year.) You need to crank up this one!

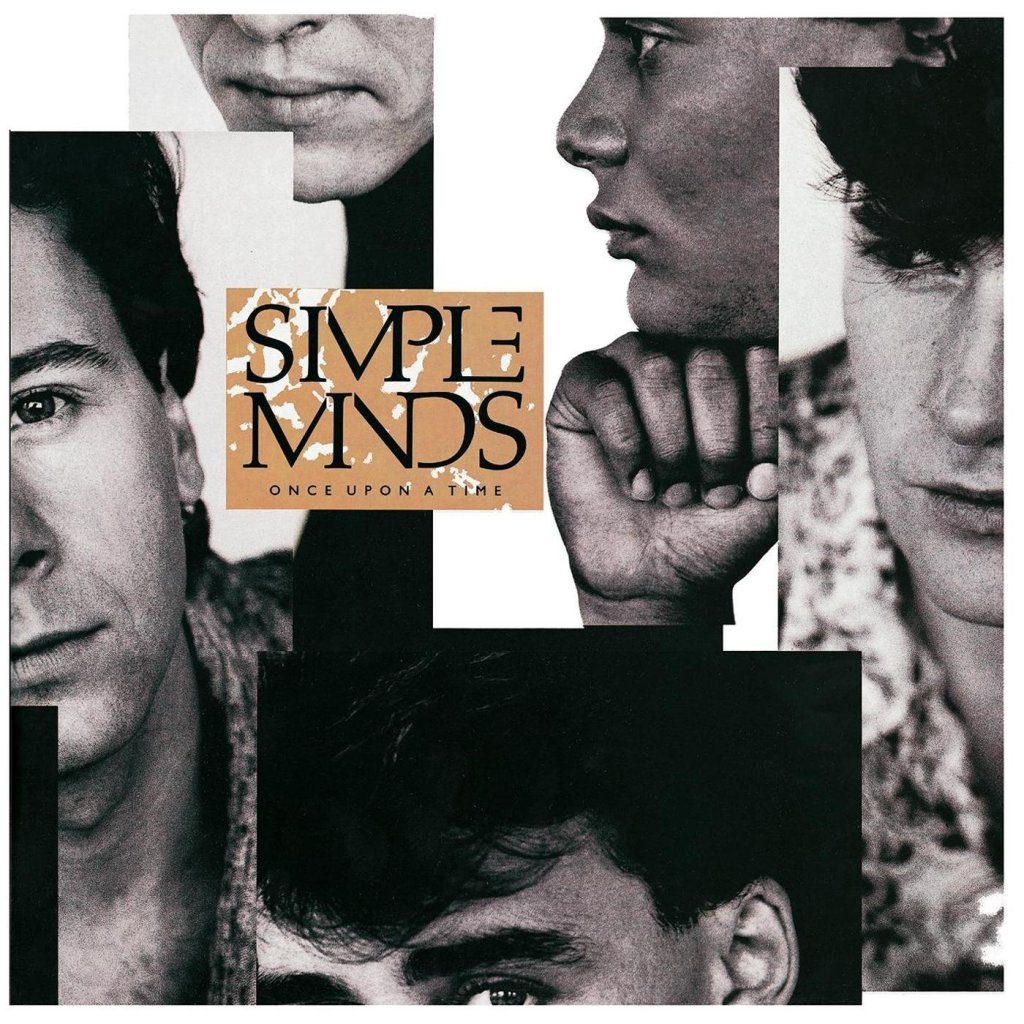

“All the Things She Said,” Simple Minds, 1985

One of England’s greatest bands of the 80s and ’90s got its start in the late ’70s but didn’t have much success on the UK charts until their fourth album in 1981, when they began a string of seven Top Five albums (including three #1 LPs) through 1995. Here in the US, their impact was far more brief. They contributed the huge #1 hit “Don’t You (Forget About Me)” to the John Hughes teen comedy classic “The Breakfast Club” in early 1985, and followed that with a Top Ten charting for their “Once Upon a Time” LP, spawning two big hits, “Alive and Kicking” (#3) and “Sanctify Yourself” (#14). It was the third single, “All the Things She Said” (which managed only #28), that always struck my fancy. Lead singer Jim Kerr and guitarist Charlie Burchill, the band’s chief songwriting team, really hit their stride with this album, but I never understood why the next several Simple Minds releases (1989’s “Street Fighting Years,” 1991’s “Real Life” and 1995’s Good News From the Next World”) stiffed in the US, because they’re full of excellent material in the same vein as “Once Upon a Time.”

“Gypsy,” Moody Blues, 1969

It should have happened about 20 years earlier, but the great Moody Blues were finally inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2018. There has been so much great music from these pioneers of British progressive rock, especially the seven albums they released in the 1967-1972 period. Their fourth LP, 1969’s “To Our Children’s Children’s Children,” had no hit singles, but charted high on the album charts (#2 in the UK, #14 in the US). Released shortly after the moon landing, the album explored the cosmic themes of space travel and children, and the legacy of the human race. The standout track for me was “Gypsy,” yet another amazing song by the consistent singer/guitarist Justin Hayward, who wrote the majority of their better known tunes.

“Caroline,” Jefferson Starship, 1974

Singer/songwriter Marty Balin formed the Jefferson Airplane in 1965 in San Francisco when he met up with guitarist/singer Paul Kantner, and with the addition of Grace Slick, they became household names in the late ’60s as voices of the counterculture. But the group crashed and burned in 1972, with Balin bailing out when Kantner kept advocating his wild-eyed sci-fi/fantasy themes. By 1974, Kantner and Slick had teamed with new instrumentalists and re-introduced themselves as Jefferson Starship. “Dragonfly,” their first LP with that lineup, was a delicious surprise, highlighted by great stuff like “Ride the Tiger,” “That’s For Sure” and “All Fly Away.” The sleeper track, though, was “Caroline,” written and sung by none other than Balin, who was coaxed to participate. It’s a gorgeous power ballad, actually better than the huge hit “Miracles” he wrote for the “Red Octopus” #1 LP the following year.

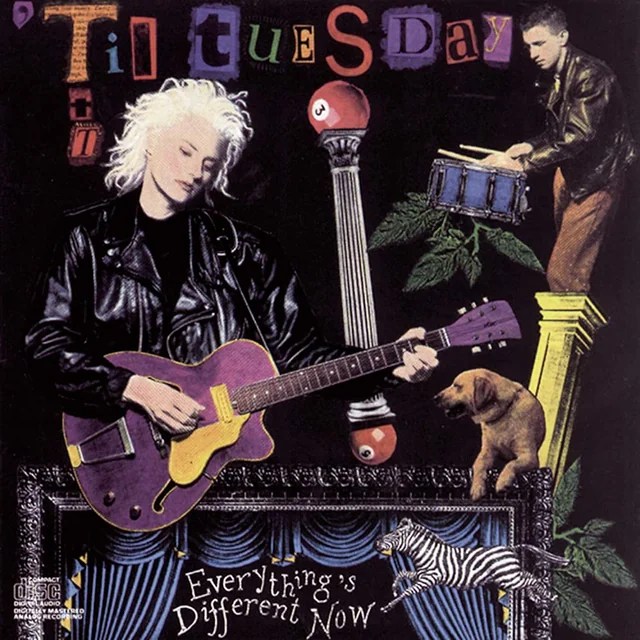

“Why Must I,” ‘Til Tuesday, 1988

Singer-songwriter Aimee Mann was the primary talent behind the ’80s alt-rock group ‘Til Tuesday, who emerged out of Boston in 1985 with the LP and Top Ten single “Voices Carry.” They lasted for two more albums before Mann headed out on her own in 1992, and she’s still touring today. I always thought ‘Til Tuesday’s second and third LPs — “Welcome Home” (1986) and “Everything’s Different Now” (1988) — were very underrated. “Coming Up Close” and “What About Love” made modest dents in the singles charts, but there were eight or ten other strong songs worthy of attention. My favorite was “Why Must I” from the 1988 LP, which features a catchy melody, inventive arrangement and great performance by Mann and her band.

“With You There to Help Me,” Jethro Tull, 1970

Tull’s 1969 second album “Stand Up” went to #1 in England, and their monumental fourth LP, 1971’s “Aqualung,” was Jethro Tull’s greatest international success, but sometimes overlooked is their third effort, 1970’s “Benefit.” It’s among their hardest rocking collections ever, with the minor hit “Teacher” appearing on the US version of the album. Ian Anderson on flute and vocals and Martin Barre on guitar were, as always, the key elements of Tull’s sound, with John Evan adding keyboard parts on some tracks for the first time. FM stations in the US gave airplay to a few tracks, most notably “To Cry You a Song” and the prog rock beauty “With You There to Help Me,” which includes a great lyric in the chorus about the warm feeling you get when you return home: “I’m going back to the ones that I know, with whom I can be what I want to be…”

“The Back Seat of My Car,” Paul McCartney, 1971

In the wake of The Beatles’ breakup in 1970, each member’s solo career was put under the microscope for intense scrutiny, as many observers felt their solo work could never measure up to the work of the band as a whole. McCartney in particular took a lot of heat for writing and recording a lot of slight, inconsequential stuff, but he was always able to come up with two or three really excellent tracks on every album. From the 1971 LP “Ram” (credited to Paul & Linda McCartney), which spawned the cutesy #1 hit “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey,” by far the strongest moment was the album closer, “The Back Seat of My Car,” beautifully arranged and performed, full of lush orchestration and voices, solid electric guitar by Paul, and a memorable repeated chorus, “Ohhh, we believe that we can’t be wrong…”

*************************