Going deep, deep in the psychedelic vault

When rock and roll was barely ten years old, some of the more adventurous musicians in England and the U.S. were eager to explore newer sounds and newer techniques that were decidedly not in the popular mainstream. These bands were all about expanding the horizons of what rock music could be, and while much of it was admittedly not very good, some of it was compelling, even catchy, and certainly influential.

There’s no denying that psychedelic drugs played a big part in motivating many bands to test the waters with musical forms that were completely unfamiliar to even the most forward-thinking listeners. Blues-based British groups like The Yardbirds, Fleetwood Mac and Cream enhanced their repertoire with innovative musical experiments, while American bands like Moby Grape, Love and Spirit took folk and rock roots and branched off into uncharted territories.

The “psychedelic rock” era didn’t last too long, roughly 1966 through 1972, but it produced some lasting music that, while not everyone’s cup of tea by a long shot, still captured the “anything goes” freedom that permeated the recording studios, especially in London, San Francisco and Los Angeles. In concert, most psychedelic music was expanded into jams with multiple solos, accompanied by mind-blowing light shows, but many of the studio recordings were held to more conventional lengths.

Instead of trotting out the same handful of spacey songs that are familiar because they made the Top 40 — “I Had Too Much to Dream Last Night” by The Electric Prunes, “Pictures of Matchstick Men” by The Status Quo, “Magic Carpet Ride” by Steppenwolf — I’ve selected a dozen very deep tracks from the late ’60s that are probably too obscure to qualify as “lost classics.” But I’m guessing there’s a segment of this blog’s audience that will get off on hearing them.

Rock on!

**************************

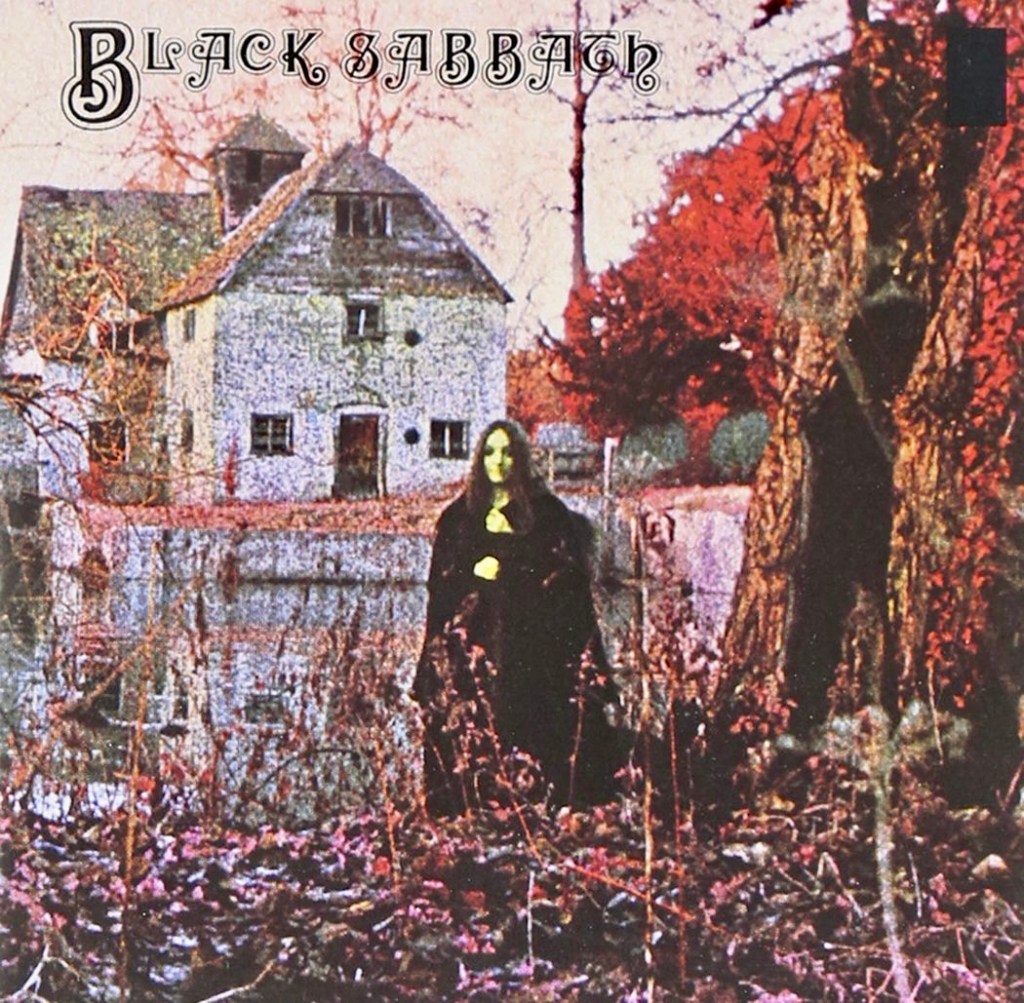

“Fresh Garbage,” Spirit, 1968

Influenced by jazz, rock and folk, L.A-based Spirit emerged in late 1967 under the tutelage of famed producer Lou Adler, who encouraged their psychedelic leanings even as he found ways to make their music more accessible to the masses (at least in California). Their albums fared reasonably well, but their singles fell flat, largely because Spirit’s audience always preferred albums. Still, songs like “I Got a Line on You,” “Mr. Skin” and “Nature’s Way” found their way onto radio eventually. From their eponymous debut LP came the inaccurately titled “Fresh Garbage,” a marvelous, jazz-inflected tune that set the stage for Spirit’s reputation as a premier underground band.

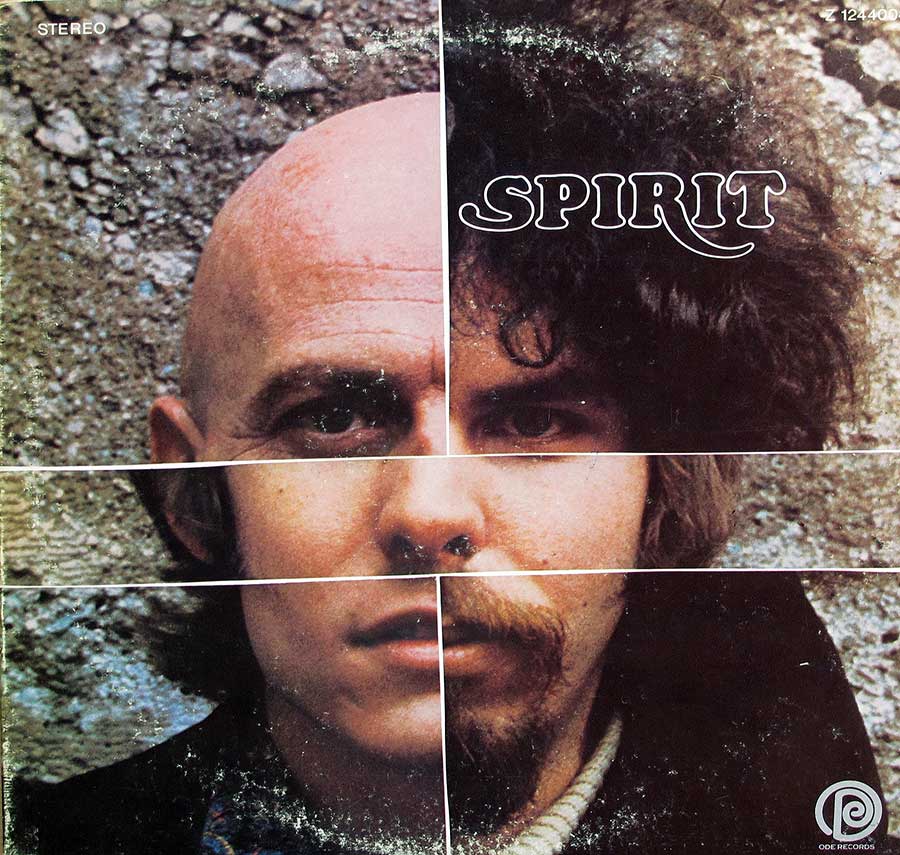

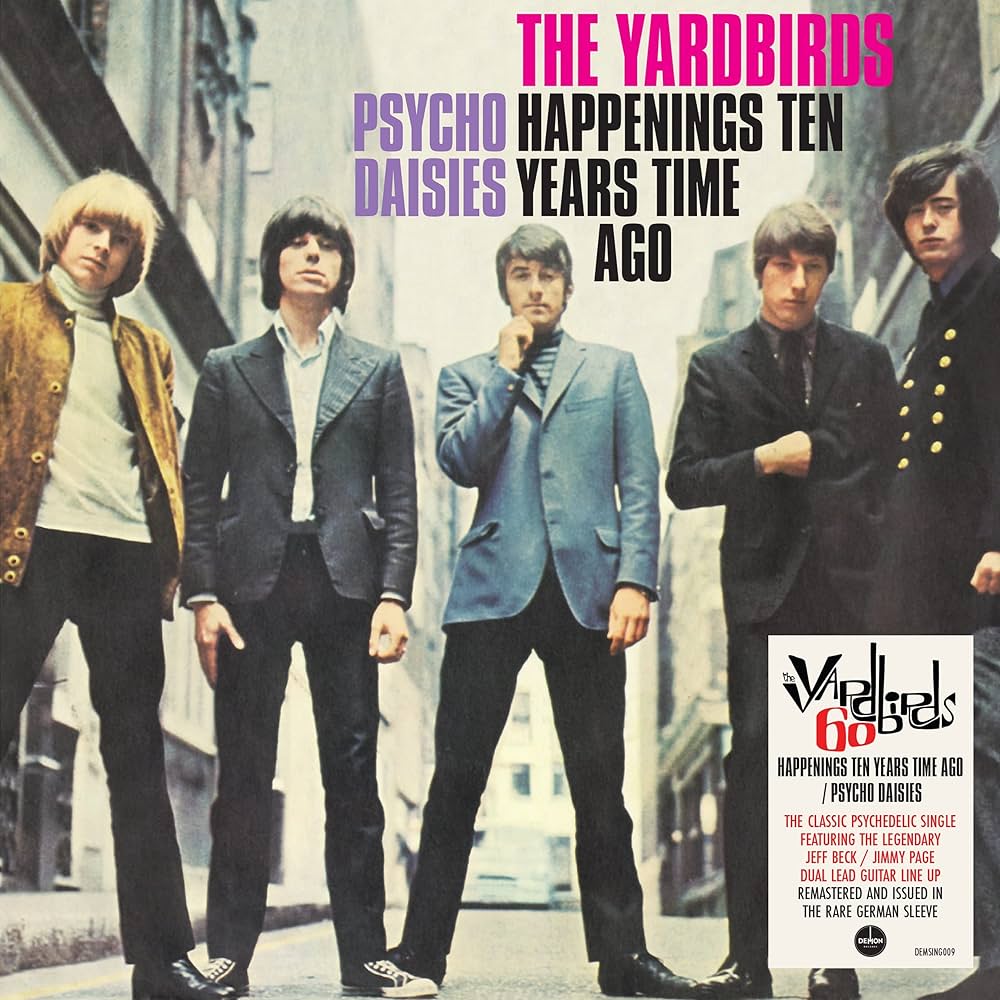

“Happenings Ten Years Time Ago,” The Yardbirds, 1966

The Yardbirds, a trailblazing blues group and proving ground for several of England’s most iconic electric guitarists, bridged the gap between blues and pop enough to land in the Top 20 of the US pop charts five times in 1965-1966: ”For Your Love,” “Heart Full of Soul,” “I’m a Man,” “Shapes of Things” and “Over Under Sideways Down.” In late 1966, their experimental (yet influential) track “Happenings Ten Years Time Ago” failed to chart here, perhaps because of its unorthodox psychedelic arrangement, lyrics about reincarnation and deja vu, and innovative guitar work by Jeff Beck and Jimmy Page, who overlapped as Yardbirds for three months.

“8:05,” Moby Grape, 1967

According to pop culture writer Jeff Tamarkin, “Moby Grape’s saga is one of squandered potential, absurdly misguided decisions, bad luck, blunders and excruciating heartbreak, all set to the tune of some of the greatest rock and roll ever to emerge from San Francisco.” Their first two albums somehow reached the Top 20 in the US in 1967 and 1968, but you’d be hard pressed to find a copy these days. The group’s three-guitarist lineup featured three singer-songwriters who merged rock, blues, folk and country in a tempting psychedelic stew. One of the better tracks is the brief, folky “8:05” by guitarist Jerry Miller.

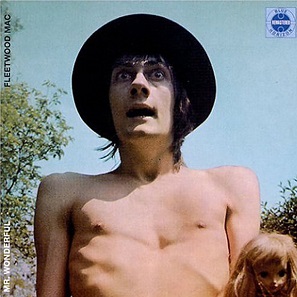

“Stop Messin’ Round,” Fleetwood Mac, 1968

In its original incarnation (1967-1970), the band was known as Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac, emphasizing the leadership roll of virtuoso blues guitarist Green, who also handled harmonica and most vocals. On their second LP (titled “Mr. Wonderful” in England but reconfigured as “English Rose” in the US), they added saxophones to several tracks, as well as piano provided by future member Christine Perfect McVie. A highlight is the original Green blues track “Stop Messin’ Round,” which opens the album. These early blues-oriented Fleetwood Mac LPs were all Top Ten successes in England but wallowed in the lower rungs of the US charts.

“Baby’s Calling Me Home,” Steve Miller Band, 1968

Before he settled into a lucrative gig as a mainstream pop/rock star of the late ’70s and early ’80s, Miller was the leader of one of San Francisco’s most promising psychedelic blues bands, cranking out five albums in less than three years, including lost classic tracks like “Space Cowboy” and “Living in the U.S.A.” One of the Steve Miller Band’s founding members was guitarist/singer Boz Scaggs, who split in 1969 for a solo career specializing in R&B and “blue-eyed soul.” On the group’s 1968 debut LP “Children of the Future,” Scaggs wrote and sang lead vocals on the bluesy “Baby’s Calling Me Home,” probably the best track on the record.

“Tin Soldier,” Small Faces, 1967

Emerging as one of the premiere psychedelic bands of London’s mod subculture in the mid-’60s, The Small Faces enjoyed eight hit singles on UK charts but only one in the US, “Itchycoo Park,” which peaked at #16 in 1967. The follow-up, “Tin Soldier,” stalled at #73 in the US but prompted the release of “There Are But Four Small Faces,” their first US album which reconfigured the UK version by dropping some tracks and adding the two singles, both written by guitarist Steve Marriott. When Marriott left in 1969 to form Humble Pie, the others (including Ronnie Lane and Kenney Jones) continued as The Faces with Ron Wood on guitar and Rod Stewart on vocals.

“A House is Not a Motel,” Love, 1967

Arthur Lee, the frontman of the L.A. band Love, wrote unusual songs that deftly amalgamated garage rock, folk rock and psychedelia. He and guitarist Bryan MacLean steered the group from L.A. clubs to a national record contract, even scoring one minor hit, “7 and 7 Is,” which peaked at #33 in 1966. But Love was without question an album band, and their 1967 LP “Forever Changes” is considered a defining work of underground California rock, even as it investigated darker themes and questioned the sunny optimism of the so-called “Summer of Love” that year. In particular, “A House is Not a Motel” uses a folky foundation and then soars off into psychedelic realms.

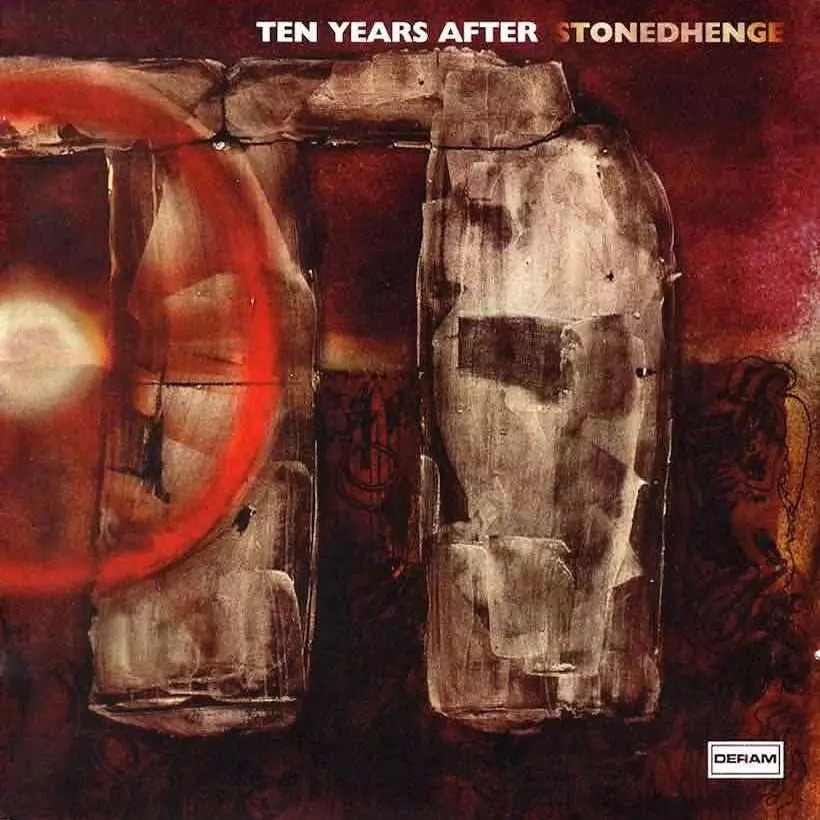

“Hear Me Calling,” Ten Years After, 1969

British blues-rock band Ten Years After formed in 1966, named because they were born “ten years after” the explosive success of Elvis Presley, guitarist Alvin Lee’s idol. The group had four Top Ten LPs in the UK in 1969 and 1970, and generated a decent following in the US as well, thanks to a game-changing performance of Lee’s “I’m Going Home” at Woodstock, which was featured in the film and soundtrack album. From their third LP “Stonedhenge” comes the driving blues-boogie “Hear Me Calling,” written and sung by Lee, who wrote most of the band’s catalog, including their one US Top 40 entry, “I’d Love to Change the World” in 1971.

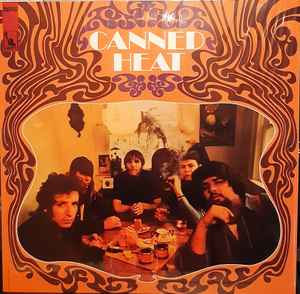

“Help Me,” Canned Heat, 1967

Bob “The Bear” Hite was a blues aficionado living in the Topanga Canyon area of L.A. when he formed Canned Heat as a makeshift jug band playing folk blues music, immortalized in the “Woodstock” soundtrack with its single “Going Up the Country.” Their self-titled debut LP consisted mostly of covers of tunes by the people Hite considered the best of the Delta bluesmen — Robert Johnson, Elmore James, Muddy Waters, Willie Dixon. Although Hite was Canned Heat’s gruff lead singer, the track “Help Me” by Sonny Boy Williamson II features guitarist Alan Wilson on vocals. The group was lauded as “one of America’s best boogie bands who also delve into psychedelic funk.”

“N.S.U.,” Cream, 1967

Eric Clapton had already made his mark with The Yardbirds and John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers when he joined forces with bassist/vocalist Jack Bruce and drummer Ginger Baker to form the blues power trio Cream, known for unparalleled live improvisational forays and creative original songs featuring the virtuoso trio in the studio. BBC writer Sid Smith said Cream’s music “is when blues, pop and rock magically starts to coalesce to create something brand new.” Their debut LP “Fresh Cream,” released in late 1966 in England, included the hit “I Feel Free” and the cryptically titled “N.S.U.,” which Bruce later revealed meant “non-specific urethritis,” a joking reference to Clapton’s bout with VD at the time.

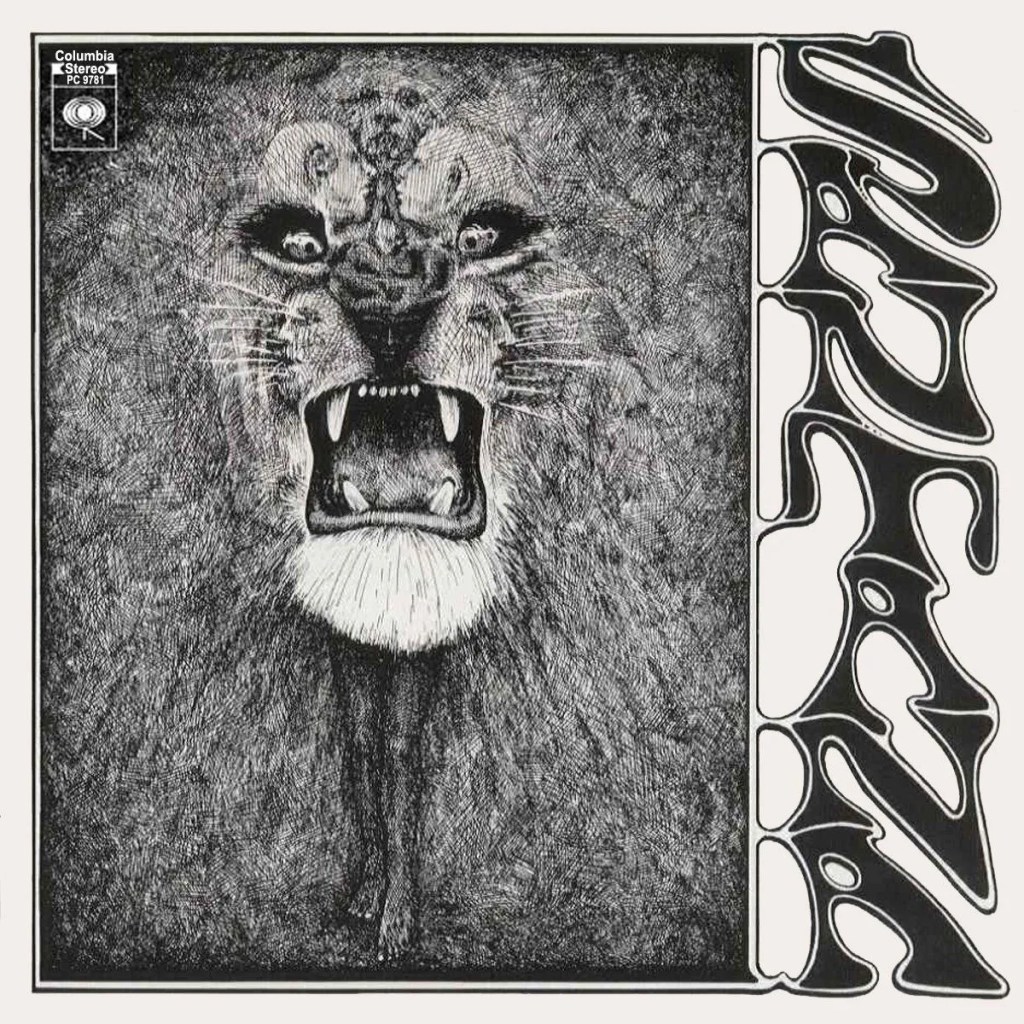

“Waiting,” Santana, 1969

Carlos Santana had emigrated from Mexico to California in his early 20s, bringing his Latin music influences to the psychedelic milieu of the San Francisco counterculture. His first project, The Santana Blues Band, fell by the wayside when some members didn’t take their gigs seriously, but once Fillmore West impresario Bill Graham got involved, along with keyboardist/vocalist Gregg Rolie, the new lineup called themselves simply Santana and finagled their way onto the bill at Woodstock, almost stealing the show with a breakout performance. “Waiting,” a percussion-driven instrumental track, opens their debut LP, released two months after the festival.

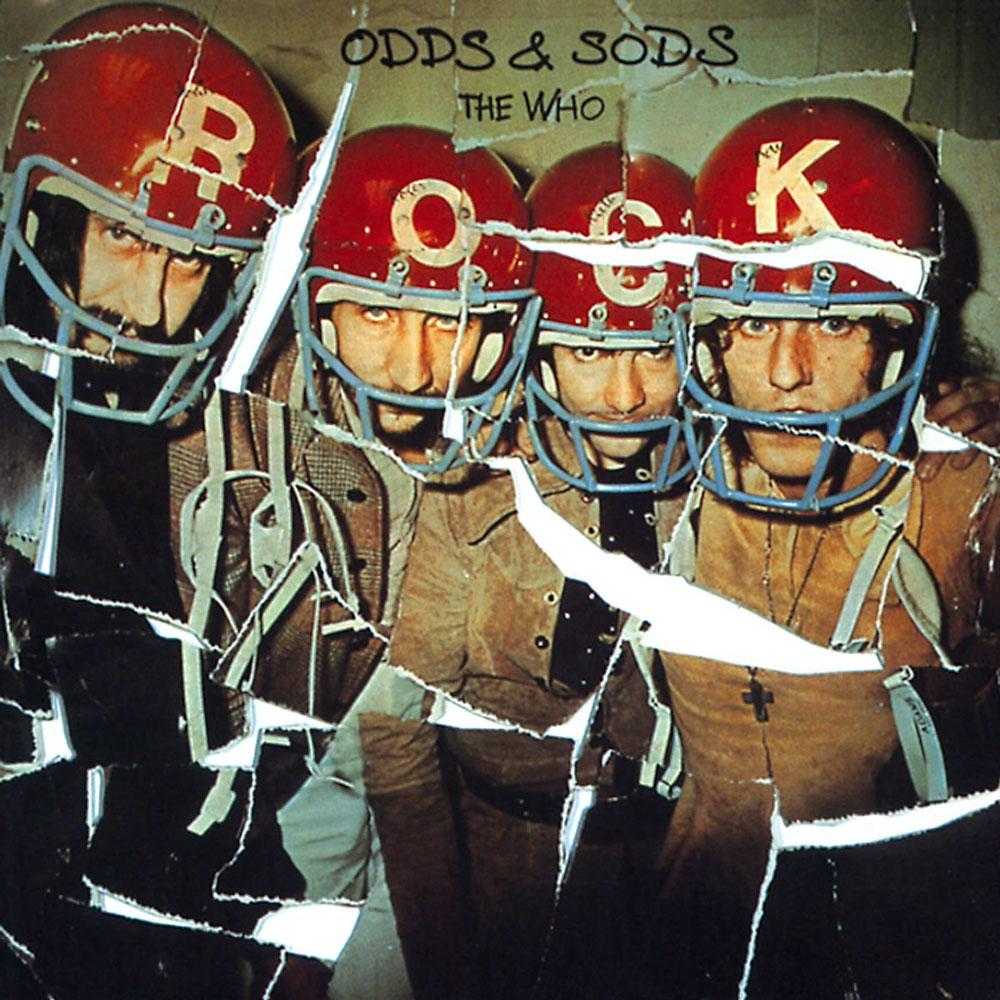

“Glow Girl,” The Who, 1968

Pete Townshend was a prolific songwriter, especially in the group’s early Mod days when The Who released multiple hit singles and B-sides and left numerous outtakes from their album sessions in the studio vault. By the mid-’70s, they decided they had enough worthwhile archival tracks to compile “Odds & Sods,” a collection of a dozen great unreleased Who tunes like “Pure and Easy,” “Postcard,” “Little Billy” and the anthem-like “Long Live Rock.” Another fine track, “Glow Girl,” was written and recorded during the 1968 sessions for “Tommy.” The lyric “It’s a girl, Mrs. Walker, it’s a girl” makes it a sort of companion piece to the brief introductory song “It’s a Boy” from the 1969 rock opera.

******************************