Nice ‘n’ easy does it every time

Most fans of rock music, even those now in their 50s and 60s, have probably forgotten (or maybe never knew) what the pop music scene looked like before rock and roll arrived in the mid-’50s.

This blog purports to look at “Musical Milestones, 1955-1990,” and I have explored virtually every sub-group from those three-plus decades: early rock and roll (Chuck Berry, Elvis Presley); the blues (Howlin’ Wolf, The Allman Brothers); surf music (The Beach Boys, The Rivieras); Motown (Smokey Robinson, The Supremes); the British Invasion (The Beatles, The Rolling Stones); folk rock (The Byrds, Simon and Garfunkel); garage rock (The Standells, The Troggs): psychedelic rock (Jimi Hendrix, Cream); singer-songwriter (James Taylor, Joni Mitchell); country rock (The Eagles, Poco); progressive rock (Pink Floyd, Jethro Tull); disco (The Bee Bees, Donna Summer); heavy metal (Black Sabbath, Kiss); reggae (Bob Marley, Peter Tosh); new wave (Blondie, Elvis Costello).

But up until now, I’ve neglected to explore the one genre that has endured, in one form  or another, alongside all of these: “Easy listening.”

or another, alongside all of these: “Easy listening.”

The very name sends shudders up the spine of most rock music fans. It conjures up images of straight-laced crooners singing saccharine-sweet love songs you might hear in medical building elevators or Vegas cabarets.

That generalization, like most generalizations, has truth in it, but it’s also quite unfair. Let’s look at the record (or records).

Before rock music arrived, almost everything on pop radio — or “the hit parade,” as it was called then — was what we eventually called Easy Listening. It certainly wasn’t labeled as such, however; it was simply “popular music” — records that featured vocalists singing over orchestral arrangements, doing songs from the “Great American Songbook,” Broadway show tunes, jazzy ballads, romantic torch songs and post-Swing era standards.

Before rock music arrived, almost everything on pop radio — or “the hit parade,” as it was called then — was what we eventually called Easy Listening. It certainly wasn’t labeled as such, however; it was simply “popular music” — records that featured vocalists singing over orchestral arrangements, doing songs from the “Great American Songbook,” Broadway show tunes, jazzy ballads, romantic torch songs and post-Swing era standards.

The vocal stylings of Frank Sinatra, Tony Bennett, Peggy Lee, Nat King Cole, Vic Damone, Doris Day, Perry Como, Dinah Shore, Mel Tormé, Frankie Laine and Rosemary Clooney ruled the roost in the early 1950s. Even after Elvis Presley and other rock and rollers elbowed their way onto the charts in the latter half of the decade, Sinatra and company were still large and in charge, their ranks bolstered by a newer crop of crooners — Johnny Mathis, Andy Williams, Vic Damone, Vikki Carr, Dean Martin and Barbra Streisand — who came along in the late ’50s or early ’60s.

And, as we shall see, this music had serious staying power. Here’s a tidbit that will rock the world of you stoners out there: The Mathis collection “Johnny’s Greatest Hits,”

Johnny Mathis

released in 1958, spent an unprecedented 490 consecutive weeks on the Billboard top 100 album charts (that’s more than nine years). It held the record for the most number of weeks on the Top 200 album chart in the US until Pink Floyd’s “Dark Side of the Moon” LP reached 491 weeks in October 1983.

The term “Easy Listening” was coined by radio formatters who needed a way to distinguish vocalists singing in the style established in the 1930s and 1940s from singers who adopted a style closer to rock and roll. If you look at the best-selling artists of the 1955-1959 period, Presley was the only rock star in the bunch. The majority were singers of the Sinatra/Mathis variety, along with instrumental/choral maestros like Mantovani, Lawrence Welk, Jackie Gleason (!) and The Ray Conniff Singers.

Indeed, Gleason — a comedian who enjoyed a remarkably potent side career as a songwriter/arranger — struck upon a quintessential “easy listening” formula he felt was inherently marketable. His goal was to make “musical wallpaper that should never be intrusive, but conducive to romance.” He saw how love scenes in the movies were “magnified a thousand percent” by the background music, and concluded, “If Clark Gable needs music to get the job done, a guy in Brooklyn must be desperate for that kind of help!”

Indeed, Gleason — a comedian who enjoyed a remarkably potent side career as a songwriter/arranger — struck upon a quintessential “easy listening” formula he felt was inherently marketable. His goal was to make “musical wallpaper that should never be intrusive, but conducive to romance.” He saw how love scenes in the movies were “magnified a thousand percent” by the background music, and concluded, “If Clark Gable needs music to get the job done, a guy in Brooklyn must be desperate for that kind of help!”

Doris Day

By 1960, white-bread teen idols like Brenda Lee, Bobby Vee, Connie Francis and Paul Anka made a significant dent in the charts for a spell, sometimes blurring the line between genres by favoring schmaltz (Anka’s “Tonight My Love, Tonight”) over young heartache (Vee’s “Take Good Care of My Baby”). But even as R&B artists from The Miracles and Ben E. King to Chubby Checker and Jackie Wilson began adding their earthy approach to the mix, and Broadway show tunes and themes from film soundtracks periodically topped the charts, the Easy Listening artists hung on strong.

Andy Williams

It’s not hard to see why. Most of the pop music audience at that time was from a generation that liked their music traditional, melodious, nostalgic, even sentimental. Rock and roll, and all that followed in its wake, was, to them, unpleasant, harsh, even non-musical. Give them “Moon River” and “Mona Lisa” any day.

In my family household in the early 1960s, I remember hearing a lot of pretty music coming from my dad’s “hi fi” — a lot of Sinatra and Nat King Cole, plus Como, Mathis, Williams, Jo Stafford and Jack Jones. Now and then, Dad would also play big band and swing music by the orchestras

Perry Como

of Tommy Dorsey and Benny Goodman, but mostly I recall the gentle strains of romantic ballads with lush string arrangements.

But the burgeoning teen audience was on the rise, and when the arrival of the Beatles and the “British Invasion” in 1964 triggered a seismic shift toward rock in the makeup of the US Top 40, the Easy Listening crew began their inexorable downslide from chart success.

Although Easy Listening music waned as a dominant force, it was clear there remained a sizable audience for it. The TV variety shows of that period — “The Dinah Shore Show,” “The Ed Sullivan Show” and “Hollywood Palace” — offered occasional

Barbra Streisand

appearances by rock groups, but for the most part, they still featured plenty of Vic Damone and Robert Goulet, and Streisand, and Vegas duos like Steve Lawrence and Eydie Gormé.

By the late ’60s, all these artists had pretty much vanished from the mainstream charts, with a few exceptions. Sinatra still managed two big hits in 1966 — “Strangers in the

Engelbert Humperdinck

Night” and “That’s Life” — and new crooners like Englebert Humperdinck and Bobby Goldsboro topped the charts in 1967 and 1968 with the cringeworthy “Release Me” and “Honey,” respectively. Some vocalists like Mathis and Williams evolved, and started capitalizing on the popularity of the singer-songwriter movement, releasing albums of covers of contemporary hits by the likes of James Taylor, Gordon Lightfoot, Carole King and even The Beatles (together and solo).

As the variety of radio formats mushroomed in the 1970s to meet ever-broadening tastes, Easy Listening music took on other names, ranging from “Music of Your Life” and “adult standards” to “Unforgettable Favorites” or, eventually, “Adult Contemporary.” Regardless of the moniker, it was considered by most rock music fans as hopelessly square and outdated.

The Carpenters

By the late 1970s, Easy Listening as a radio format had split into two camps. The diehards could tune into Adult Standard, or “Beautiful Music,” which kept the decades-old classics alive. A newer version of the genre known as Adult Contemporary featured the music of softer-sounding current artists like The Carpenters, Bread, Barry Manilow, John Denver, Seals and Crofts, Air Supply, Christopher Cross, Lionel Richie and Olivia Newton John. And stalwarts like Mathis found new life by collaborating with new singers like Deniece Williams on the Top Ten hit “Too Much, Too Little, Too Late” in 1978.

No self-respecting rocker would ever admit at that point to liking this stuff, but in secret, the fortitude of these artists to forge ahead in the face of critical lambasting was admired. Indeed, in 1988, Bob Dylan stopped Manilow at a party, hugged him and said,

Barry Manilow

“Don’t stop what you’re doing, man. We’re all inspired by you.”

Adult Contemporary still exists today, although it has further fragmented into smaller niches like “hot AC” (includes electric guitar and drums) and “soft/smooth AC” (stresses vocals and acoustic instrumentation) and even “urban AC” (black artists doing mellow music).

A personal aside: I’m a rock music guy, with a fondness for blues and classic R&B, but I have a soft spot for some of these AC artists. I consider some songs by The Carpenters, Bread and Christopher Cross (“Rainy Days and Mondays,” “Make It With You,” “Sailing”) to be guilty pleasures. They’re melodic, well produced, and full of warm memories, and there have been times I have proudly cranked up the volume, and not just when I’m alone in my car. Hey, even the most straight-laced artist has a great song or two in his/her repertoire.

In the mid-1980s, in the midst of New Wave and Madonna-type dance music, a curious thing happened. As with fashion styles that make a comeback decades after they were  first popular, we witnessed a revival of the marvelous tunes of the ’40s and ’50s. Country rock superstar Linda Ronstadt, who had been exposed to Sinatra’s music as a little girl and had always wanted to try singing the standards, rolled the dice. She paired up with legendary orchestral arranger Nelson Riddle to release “What’s New,” the first of three albums featuring her luxurious covers of some of the best traditional songs of that bygone era — Gershwin classics like “I’ve Got a Crush on You” and “Someone to Watch Over Me” and Rodgers & Hart classics such as “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered” and “It Never Entered My Mind.”

first popular, we witnessed a revival of the marvelous tunes of the ’40s and ’50s. Country rock superstar Linda Ronstadt, who had been exposed to Sinatra’s music as a little girl and had always wanted to try singing the standards, rolled the dice. She paired up with legendary orchestral arranger Nelson Riddle to release “What’s New,” the first of three albums featuring her luxurious covers of some of the best traditional songs of that bygone era — Gershwin classics like “I’ve Got a Crush on You” and “Someone to Watch Over Me” and Rodgers & Hart classics such as “Bewitched, Bothered and Bewildered” and “It Never Entered My Mind.”

Ronstadt recalled in her 2013 memoir, “Rock ‘n roll diehards in the music press wondered why I had abandoned Buddy Holly for George Gershwin. The answer is that there was so much more room for me to stretch and sing, to mix my head voice and my chest voice. And besides, I couldn’t bear the idea that such beautifully crafted songs would be condemned to riding up and down in elevators.”

Her gamble paid off handsomely. These revivals were not only an unqualified success — “What’s New” reached #3 and went triple-platinum — but also inspired quite a few other rock-era artists to release copycat collections of once-shunned material over the ensuing years.

The first to follow Ronstadt’s efforts was the spectacularly popular (7X platinum) “Unforgettable…With Love,” Natalie Cole’s 1991 Grammy-winning album of standards, capped by a spooky duet with her long-gone father Nat singing the title song “together” in a bit of remarkable studio trickery.

The first to follow Ronstadt’s efforts was the spectacularly popular (7X platinum) “Unforgettable…With Love,” Natalie Cole’s 1991 Grammy-winning album of standards, capped by a spooky duet with her long-gone father Nat singing the title song “together” in a bit of remarkable studio trickery.

Cole’s success seemed to open the floodgates as at least a dozen singers tackled the standards, with varying results. Some were quite good — Carly Simon’s “My Romance” (1990), Boz Scaggs’s “But Beautiful” (2003) and Art Garfunkel’s “Some Enchanted Evening” (2007) come to mind. Others have fallen flat — Bryan Ferry’s “As Time Goes By” (1999), Michael Bolton’s “Vintage” (2002) and Cyndi Lauper’s “At Last” (2003).

Rod Stewart has made an entire second career of it, pumping out five such albums since 2000 with erratic quality but plenty of sales. Paul McCartney and Bob Dylan, two of the best songwriters of the past half-century, recently chose to offer their treatments of songs from their parents’ generation. (McCartney had the voice to pull it off, but Dylan? Not on your life.)

Rod Stewart has made an entire second career of it, pumping out five such albums since 2000 with erratic quality but plenty of sales. Paul McCartney and Bob Dylan, two of the best songwriters of the past half-century, recently chose to offer their treatments of songs from their parents’ generation. (McCartney had the voice to pull it off, but Dylan? Not on your life.)

In the past 20 years, artists like Diana Krall, Harry Connick Jr. and Michael Bublé have become the the new millennium’s version of Sinatra and company, offering credible covers and even a few original tunes that have kept Easy Listening music alive. Before  he died in 1998, Sinatra produced two albums of standards called “Duets” and “Duets II,” which paired “The Chairman of the Board” with major contemporary artists like Bono,Gloria Estefan, Anita Baker, Stevie Wonder and Chrissie Hynde. More recently, the ageless Tony Bennett has done the same thing, singing his generation’s classics with 21st Century stars like John Legend, Carrie Underwood and John Mayer, and Lady Gaga, with whom he collaborated on an entire album.

he died in 1998, Sinatra produced two albums of standards called “Duets” and “Duets II,” which paired “The Chairman of the Board” with major contemporary artists like Bono,Gloria Estefan, Anita Baker, Stevie Wonder and Chrissie Hynde. More recently, the ageless Tony Bennett has done the same thing, singing his generation’s classics with 21st Century stars like John Legend, Carrie Underwood and John Mayer, and Lady Gaga, with whom he collaborated on an entire album.

So the way we view “our parents’ (or grandparents’) music” has come full circle, from derision and disrespect to admiration and appreciation. Not all of it, mind you; some of it will always be dismissed as mushy and trite.

I guess there are two conclusions I want to make:

1) There are musical styles to suit every taste. I don’t care for opera, or hard-core country-western, or gangsta rap, but there are plenty of folks who do, and I say, to each his own. I do enjoy a range of genres, and I try to keep my mind open. But often, sometimes  too often, I find myself leaning on “the songs of my youth” because, well, they’re familiar, and they remind me of childhood, or young adulthood, and they make me smile.

too often, I find myself leaning on “the songs of my youth” because, well, they’re familiar, and they remind me of childhood, or young adulthood, and they make me smile.

Which leads me to: 2) There is always a place for The Oldies. What constitutes an “oldie,” anyway? That depends, I suppose, on when it was released, and how old you were when you first heard it.

Easy Listening? It might be rather safe, tame, non-threatening and old-fashioned…but damn, it can be comforting. And, by the way, easy to listen to.

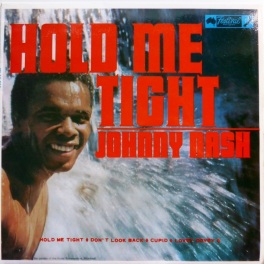

Its first appearance here, it’s generally agreed, came when an American-born artist — Johnny Nash, a Houston-based pop singer-songwriter — took his version of Jamaica’s indigenous music to #5 on the U.S. charts in 1968 with the catchy “Hold Me Tight.” But if record companies were expecting to then cash in on a flood of reggae songs and bands, it didn’t happen. (At least not yet.)

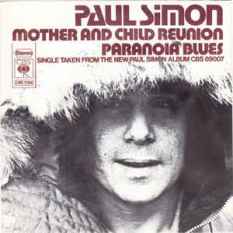

Its first appearance here, it’s generally agreed, came when an American-born artist — Johnny Nash, a Houston-based pop singer-songwriter — took his version of Jamaica’s indigenous music to #5 on the U.S. charts in 1968 with the catchy “Hold Me Tight.” But if record companies were expecting to then cash in on a flood of reggae songs and bands, it didn’t happen. (At least not yet.) So reggae went back into hiding for a few years until the great Paul Simon, always curious about “world music” and intriguing new rhythms, visited Kingston in 1971 to record his new song “Mother and Child Reunion.” He admired reggae artists like Jimmy Cliff and Desmond Dekker and wanted to explore the music further at its source, using Jamaican musicians who instinctively knew the way it should be played. He invited Cliff’s backing group to accompany him on the recording, and the result was also a #5 hit that put reggae back in the public eye.

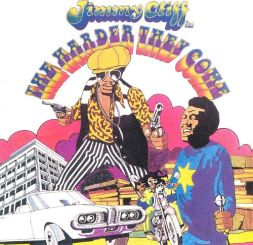

So reggae went back into hiding for a few years until the great Paul Simon, always curious about “world music” and intriguing new rhythms, visited Kingston in 1971 to record his new song “Mother and Child Reunion.” He admired reggae artists like Jimmy Cliff and Desmond Dekker and wanted to explore the music further at its source, using Jamaican musicians who instinctively knew the way it should be played. He invited Cliff’s backing group to accompany him on the recording, and the result was also a #5 hit that put reggae back in the public eye. The attention Cliff gained from that connection helped him later that year when he released “The Harder They Come,” the soundtrack album to the movie of the same name (in which he also starred). The film, a crudely made crime drama, was largely ignored but later became a favorite with the midnight-movie crowd.

The attention Cliff gained from that connection helped him later that year when he released “The Harder They Come,” the soundtrack album to the movie of the same name (in which he also starred). The film, a crudely made crime drama, was largely ignored but later became a favorite with the midnight-movie crowd. play it. I just knew we weren’t doing it right.

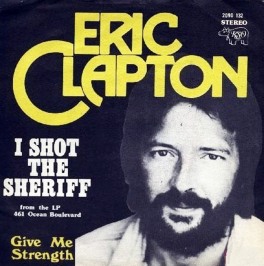

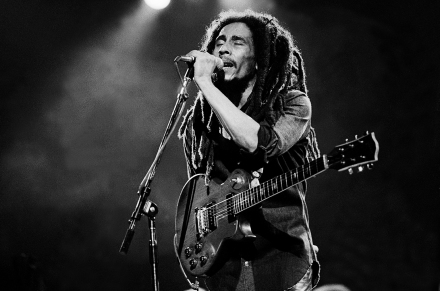

play it. I just knew we weren’t doing it right. He signed Marley to a lucrative contract in 1973, let him loose in his studios in the Bahamas and England, and sat back and waited. The debut LP, “Catch a Fire,” marked the first time a reggae band had access to a state-of-the-art studio and were accorded the same care as their rock ‘n’ roll peers. Blackwell, hoping to create “more of a drifting, hypnotic-type feel than a rudimentary reggae rhythm,” restructured Marley’s arrangements and supervised the mixing and overdubbing.

He signed Marley to a lucrative contract in 1973, let him loose in his studios in the Bahamas and England, and sat back and waited. The debut LP, “Catch a Fire,” marked the first time a reggae band had access to a state-of-the-art studio and were accorded the same care as their rock ‘n’ roll peers. Blackwell, hoping to create “more of a drifting, hypnotic-type feel than a rudimentary reggae rhythm,” restructured Marley’s arrangements and supervised the mixing and overdubbing. pop charts, the album soared to #8 and the 1977 followup “Exodus” (with the FM hits “Jammin’,” “Waiting in Vain” and “Three Little Birds”) was a respectable #20.

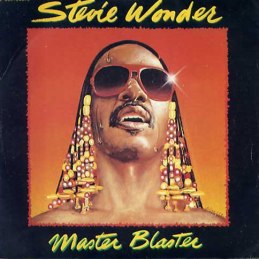

pop charts, the album soared to #8 and the 1977 followup “Exodus” (with the FM hits “Jammin’,” “Waiting in Vain” and “Three Little Birds”) was a respectable #20. In America, Motown/funk superstar Stevie Wonder was so taken by reggae in general, and Marley in particular, that he wrote a tribute to him in 1980 called “Master Blaster (Jammin’),” which became a #5 hit in the US and #2 in England. Marley and Wonder even performed several shows together that summer.

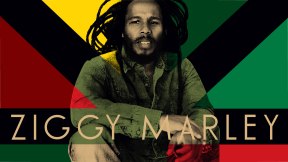

In America, Motown/funk superstar Stevie Wonder was so taken by reggae in general, and Marley in particular, that he wrote a tribute to him in 1980 called “Master Blaster (Jammin’),” which became a #5 hit in the US and #2 in England. Marley and Wonder even performed several shows together that summer. since then, most notably Ziggy in the late ’80s (particularly “Tomorrow People” in 1988) and Damien in the ’90s, perpetuating and growing the reach and influence of reggae music as their father intended.

since then, most notably Ziggy in the late ’80s (particularly “Tomorrow People” in 1988) and Damien in the ’90s, perpetuating and growing the reach and influence of reggae music as their father intended.