We just want to give gratitude

Melody Beattie, a pioneer of the self-help movement and a recovering addict herself, has written many inspirational books that have assisted many thousands on how to live fuller, more productive lives. She has said that being grateful for life’s blessings is a crucial component, and she wrote this marvelously succinct summary of the concept:

“Gratitude unlocks the fullness of life. It turns what we have into enough, and more. It turns denial into acceptance, chaos to order, confusion to clarity. It can turn a meal into a feast, a house into a home, a stranger into a friend. It turns problems into gifts, failures into successes, the unexpected into perfect timing, and mistakes into important events. It can turn an existence into a real life, and disconnected situations into important and beneficial lessons. Gratitude makes sense of our past, brings peace for today, and creates a vision for tomorrow. Gratitude makes things right.”

In this special Thursday post on this music blog, I have gathered a dozen songs of gratitude from as far back as 1935 and as recent as 2018. They each focus on the importance of being thankful for what we have in a world where we sometimes forget that. There’s a Spotify playlist at the end for your listening pleasure.

Happy Thanksgiving!

****************************

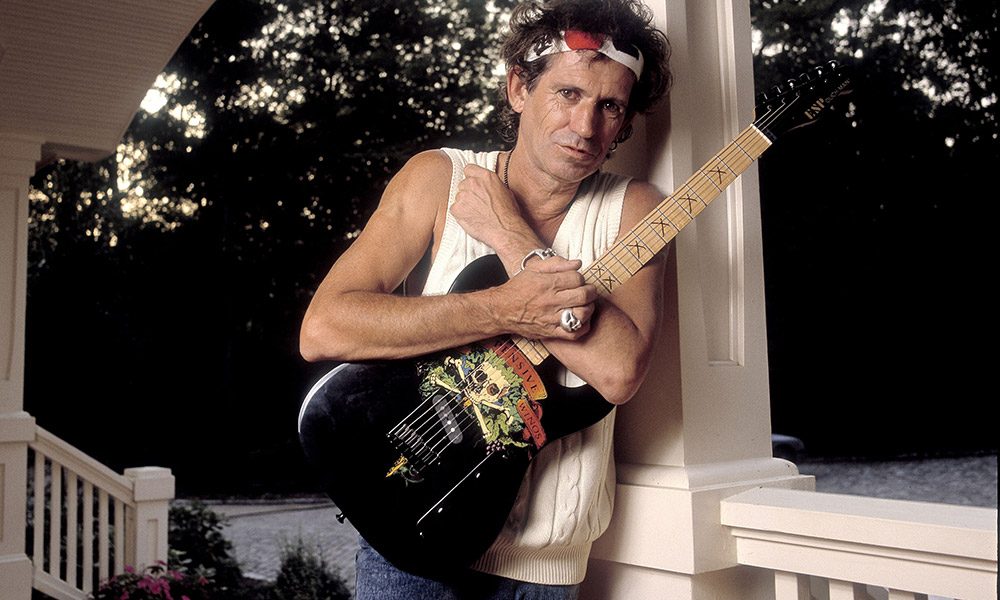

“My Thanksgiving,” Don Henley, 2000

Henley collaborated with former Heartbreakers drummer Stan Lynch to write several songs for his overlooked 2000 album “Inside Job,” including this poignant tune about a man looking back with regret on his years gone by, and the blessings he didn’t appreciate at the time. The message of this song, it seems to me, is that it’s never too late to be grateful: “And I don’t mind saying that I loved it all, I wallowed in the springtime, now I’m welcoming the fall, for every moment of joy, every hour of fear, for every winding road that brought me here, for every breath, for every day of living, this is my thanksgiving…”

“Thanksgiving Prayer,” Joanne Cash, 2018

Country music icon Johnny Cash died in 2003, but his younger sister Joanne began her own musical career four years later at the age of 69 with the release of “Gospel” in 2007, the first of four LPs the deeply spiritual singer has produced. In 2018, the LP “Unbroken” included a dozen songs of religious devotion, including Josef Anderson’s sensitive “Thanksgiving Prayer,” which expresses gratitude for lifer’s blessings: “We’ve come to the time in the season when family and friends gather near /To offer a prayer of Thanksgiving for blessings we’ve known through the years… /I’m grateful for the laughter of children, the sun and the wind and the rain, /The color of blue in your sweet eyes, the sight of a high ballin’ train, /The moon rise over a prairie, an old love that you’ve made new, /And this year when I count my blessings, I’m thanking the Lord He made you…”

“I Want to Thank You,” Otis Redding, 1965

Soul music giant Redding was generally regarded as an interpreter of other composers’ works, but he also wrote a handful of original tunes, including “Respect,” the song that became Aretha Franklin’s signature piece. In 1965, on his second LP, “The Great Otis Redding Sings Soul Ballads,” he offered “I Want to Thank You,” a song of gratitude for the love and support of a woman who died prematurely: “I want to thank you for being so nice now, I want to thank you for giving me my pride, /Sweet kisses too, and everything you do, /I know I’ll never find another one like you…” Redding himself perished far too young at age 26 in a plane crash in 1967.

“Thanksgiving Song,” Mary Chapin-Carpenter, 2008

This talented singer-songwriter of country and folk music emerged from the Washington DC area in 1987, first reaching the Top Ten on US album charts in 1994 with “Stones in the Road.” She had an impressive run of Top Ten singles on country charts throughout the 1990s with original songs like “I Feel Lucky,” “Passionate Kisses,” “He Thinks He’ll Keep Her” and “Shut Up and Kiss Me.” In 2008, Chapin-Carpenter released “Come Darkness, Come Light: Twelve Songs of Christmas,” which featured “Thanksgiving Song,” a gentle song that conveys a significant message: “Grateful for what’s understood, and all that is forgiven, /We try so hard to be good, to lead a life worth living, /Father, mother, daughter, son, neighbor, friend, and friendless, /All together, everyone, let grateful days be endless…”

“Thanks to You,” Boz Scaggs, 2001

An original member of the Steve Miller Band in the late ’60s, Scaggs went solo in 1969 and had three Top Ten albums in the late ’70s including the platinum “Silk Degrees” with the hit “Lowdown.” He has continued to release smooth new LPs every 4-5 years through the decades since. In 2006, his overlooked album “Dig” included the heartfelt closer “Thanks to You,” a poignant ode to a life partner who provides much-needed love and support “as I balk and stumble through the world.” “Thanks to you,

I’ve got a reason to get outta bed make a move or two, /Thanks to you, there’s a net below, ’cause otherwise, well I don’t know, /And thanks to you, there are promises of laughs and loves and labyrinths, /And reason to suspect that I’m meant for this, a smile, a song, a tender kiss, /Thanks to you…”

“(I’ve Got) Plenty to Be Thankful For,” Bing Crosby, 1942

From the mid-1920s well into the 1960s, Crosby was a leading singer, actor and radio star, a winner of Oscars and Grammys, and most famous for his recording of the seasonal classic “White Christmas,” first heard in the 1942 film “Holiday Inn.” That movie soundtrack featured a dozen other songs by the great Irving Berlin, each commemorating various holidays (Easter, Independence Day, Valentine’s Day) as part of the film’s plot. For Thanksgiving, Bing sings Berlin’s “(I’ve Got) Plenty to Be Thankful For,” with these lyrics of gratitude: “I’ve got eyes to see with, ears to hear with, /Arms to hug with, lips to kiss with, /Someone to adore, how could anybody ask for more? /My needs are small, I buy ’em all at the five and ten cent store, /Oh, I’ve got plenty to be thankful for…”

“Thankful ‘n Thoughtful,” Sly and the Family Stone, 1973

“Fresh,” the third of three enormously influential progressive-funk LPs released by Sly and The Family Stone in the 1969-1973 period, found Stone offering a lighter, more accessible version of the psychedelic soul found on “Stand!” and “There’s a Riot Goin’ On.” A typical example of this was the tune “Thankful N’ Thoughtful,” which explores Sly’s feelings about his drug excesses and how he found his way back from dark places: “From my ankle to the top of my head, I’ve taken my chances, hah, I could have been dead, /I started climbing from the bottom, oh yeah, all the way to the top, /Before I knew it, I was up there, you believe it or not, /That’s why I got to be thankful, yeah yeah, I got to be thoughtful, /Thankful, gotta be thoughtful…”

“Thank You,” Led Zeppelin, 1969

This dreamy track sits in stark contrast to the hard blues rock that makes up most of “Led Zeppelin II,” one of the undisputed pillars of the classic rock era. It’s a dramatic ballad carried along by harmonious electric and acoustic guitars and subtle organ, and a delicate melody sung by Robert Plant, who wrote the lyrics as a loving tribute to his wife: “And so today, my world it smiles, your hand in mine, we walk the miles, thanks to you it will be done, for you to me are the only one…”

“Thanks a Million,” Louis Armstrong, 1935/1991

The songwriting team of Arthur Johnston and Gus Kahn wrote this jazzy number with Louis “Satchmo” Armstrong in mind, who recorded it in 1935 at the height of his popularity, although it wasn’t released as a single. In 1991, it appeared on “Volume 1: Rhythm Saved the World,” part of a compilation of his Decca Records catalog. Kahn’s lyrics express how grateful the singer is for his lover: “Thanks a million, a million thanks to you, /For everything that love could bring, you brought me, /Each tender love word you happened to say is hidden away in memory’s bouquet, /Thanks a million, for I remember too, /The tenderness that your caresses taught me, /You made a million dreams come true, and so I’m saying, Thanks a million to you…”

“Thanksgiving Day,” Tom Chapin, 2010 (original 1990)

Chapin’s older brother Harry established himself as a writer and singer of superb story-songs in the 1970s (“Taxi,” “Cat’s in the Cradle,” “Sniper”). Concurrently, Tom Chapin forged his own career in entertainment on children’s TV programs and on records beginning in 1976. Although never a big success on the charts, the younger Chapin has released many LPs of simple songs meant for all ages. His 1990 album “Mother Earth” was expanded in 2010 to include more songs including “Thanksgiving Day,” which explores the holiday’s history and evolution: “Everything changes, yes, even Thanksgiving, /Let’s rededicate this old day to helping the hungry, the poor and the homeless so all may be able to say, /Thanks for our health, thanks for our hearth and the bounty that grows from the ground, /With our loved ones near, we bless the year that’s brought us safely ’round…”

“Thanks,” The James Gang, 1970

Joe Walsh was just 22 when he became the guitarist, singer and chief songwriter of Cleveland’s heroes, The James Gang. Walsh’s songs “Funk #49” and “Walk Away” became national hits, and Walsh himself went on to become a major star in his own right, first as a solo act and then as a member of The Eagles. On the 1970 album “James Gang Rides Again,” Walsh wrote a largely acoustic track called simply “Thanks,” which took a somewhat resigned, matter-of-fact approach to life: “Thanks to the hand that feeds you, give the dog a bone, thanks to the man that gives you, haven’t got your own, that’s the way the world is, woh-oh…”

“Thanks For the Memory,” Rod Stewart, 2005

Lyricist Leo Robin teamed up with composer Ralph Rainger to write several popular songs from movie soundtracks, including the witty “Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” from “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” (1949) and the sentimental “Thanks For the Memory” from “Big Broadcast of 1938,” which won the Best Song Oscar that year. In the film, Bob Hope and Shirley Ross play a divorced couple who run into each other on a cruise ship and, after singing this song to each other, eventually choose to reunite. Artists like Hope, Dorothy Lamour, Bing Crosby, Ella Fitzgerald and Frank Sinatra recorded it in the years since, and rocker Rod Stewart covered it on the fourth volume of his Great American Songbook series in the 2000s. “Thanks for the memory of faults that you forgave… /And how are all those little dreams that never did come true? /Awfully glad I met you, cheerio and toodle-oo, /Thank you, thank you so much…”

*******************************