The lights go down, they’re back in town

Do you remember your first rock concerts?

I do, but that’s largely because I’ve always been an obsessive list maker. I have lists of every album I ever bought, every CD I ever bought, every cassette mixed tape I ever made.

Beginning at age 13, I began a list of every music concert I’ve ever attended — who performed, who warmed up, where it was, when it was, and who went with me — and have continued maintaining that list over the 57 years since then.

From 1968 to 2025, I’ve been to 415 concerts, many of which I reviewed as a rock music critic for newspapers in Cleveland, Ohio in the ’70s and ’80s. I was going to sometimes eight or ten shows a month at that point.

In my early years, though, I went to only about a dozen shows total before heading off to college. The bands I chose to see in concert covered a surprisingly wide range, from British progressive rock groups to mellow American singer-songwriter types. As I think back on those shows, I must say some of them made little to no impact, while others were so superb that they inspired me to spend my hard-earned cash on several hundred more concerts in the ensuing decades.

Here, then, are my memories — some vague, some vivid — of the first dozen music concerts I attended. Perhaps these memories will get you thinking about your first concert experiences. I encourage you to share with me your recollections of those first shows. I’d love to hear about them!

*********************

October 27, 1968: Simon and Garfunkel, at Public Hall, Cleveland

For my first live music concert, my friend and I went without our parents’ knowledge. My friend Paul and I were only 13, and we went with his older brother and his friend, via his friend’s parents’ car, into downtown Cleveland on a Sunday night to cavernous Public Hall to enjoy the dulcet harmonies of Simon and Garfunkel. It was a poor venue for their quiet music, but the crowd was reasonably respectful, so the sound was relatively okay. We had a crummy vantage point, more than halfway back on a flat auditorium floor, craning our necks to see the two men singing along to Simon’s lone accompanying guitar. They were touring in support of their hugely popular “Bookends” album, which included “America,” “Fakin’ It,” “Hazy Shade of Winter” and the #1 hit “Mrs. Robinson,” and I was thrilled to be in the same room with these two world-class harmonizers. I just wish we’d had better seats so I could remember the show more clearly…

October 24, 1969: Led Zeppelin, with Grand Funk Railroad, at Public Hall, Cleveland

What a difference a year makes! I was in ninth grade, now buying a lot of rock music albums to complement my mellower stuff, and I was eager to check out Led Zeppelin, the new British hard rock/blues band I’d turned on to only six months before. My friends Steve and Andy were hell-bent on going, and I eagerly agreed. I have no idea how I got my parents to agree to let me go, but sure enough, the three of us headed downtown several hours early that Friday afternoon to the same huge venue I’d been to the previous year. If you can believe it, tickets were only $4.00 each (!), and they were general admission (!!!), which meant we might get really good seats if we got lucky. When they opened the doors, there was a crush of people fighting to get in, and once we survived that, we ran to claim seats in the 20th row. Damn, I was so excited! Eventually, the announcer said, “Will you please welcome, from Flint, Michigan, GRAND FUNK RAILROAD!!” I thought, uh oh, did we come to the wrong place? But no, this was a warm-up band, so I thought, “Wow, a bonus!” This trio blew the hinges off the place for 45 minutes, songs like “Time Machine” and “Are You Ready,” and the crowd responded thunderously. Me? I was in such total awe, I was almost satisfied to leave at that point. But of course we stayed, and soon, out came the soon-to-be-legendary Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, John Paul Jones and John Bonham, still young and hungry, and ready to slay us with songs from their brand new LP, “Led Zeppelin II,” featuring the new single, “Whole Lotta Love.” We watched with our mouths agape as they played “Dazed and Confused,” “Bring It On Home,” “Heartbreaker,” “Good Times Bad Times” and others from their first two albums. We inched closer to the front as the evening drew to a close, and by the encore, we were leaning against the stage, watching Plant howling into the microphone right above us as Page wailed away on his Gibson Les Paul only a few feet away. A life-changing experience…

November 22, 1970: Chicago, at John Carroll University, the suburbs of Cleveland

The huge 1970 hit singles “Make Me Smile” in May and “25 or 6 to 4” in August had transformed Chicago from a cult favorite to a mainstream favorite, but at this stage, they were still finishing off a set of gigs scheduled in college gyms. John Carroll was a small college campus only 10 minutes from home in the Eastern Cleveland suburbs, so it was conveniently located. Two friends and I waited with the crowd outside and, again with general admission tickets, made our way into the gym and sat midway back on the left-side bleachers. The band, with its original lineup, was in top form, with guitarist/vocalist Terry Kath, bassist/vocalist Peter Cetera and keyboardist/vocalist Robert Lamm leading the charge. They performed just about everything from their widely praised first two LPs (1969’s “Chicago Transit Authority” and 1970’s “Chicago”) and a couple from the soon-to-be-released “Chicago III.” I remember the band exceeding my expectations, especially on “Beginnings,” “Does Anybody Know Really Know What Time It Is,” “25 or 6 to 4” and the album tracks “Poem for the People” and “In the Country.” Great show!!

August 29, 1971: Roberta Flack, with Cannonball Adderley & Les McCann, Blossom Music Center, outside Cleveland

Blossom Music Center had opened in 1968 as “the summer home of the Cleveland Orchestra” in an idyllic plot of land between Cleveland and Akron. The featured acts in those early years leaned toward jazz and folk artists, in keeping with the wishes of the conservative board of trustees. (The profitable rock bands showed up in the mid-’70s and have dominated the proceedings pretty much ever since.) My friend Paul, who had moved to Canada but was back in town for a visit, had become an aficionado of jazz, and he suggested we check out Blossom to see the Cannonball Adderley Quintet and Les McCann, who were warming up for Roberta Flack. I knew next to nothing about any of these artists, but it sounded like fun, so I agreed. Neither of us can remember much of anything about the music we heard that night — I later learned to like Flack’s songs, and now have enormous admiration for Adderley as well as McCann and his other jazz cohorts. But all we seem to recall of that evening is the horrendous traffic jam getting in and out of the place (and it’s been a perennial problem at Blossom ever since)…

October 3, 1971: Gordon Lightfoot, at Music Hall, Cleveland

The downtown Cleveland facility that housed the 10,000-seat Public Hall also included a smaller, 3,000-seat theater called Music Hall, which featured artists and stage shows that attracted smaller audiences. I got my first taste of that venue with my high school girlfriend Betsy when we went to see the great Gordon Lightfoot, Canada’s premier singer-songwriter. We were crazy about him, and at the time, he was riding the success of his marvelous Top Ten hit “If You Could Read My Mind” and the impressive repertoire he’d built up since his debut in the mid-’60s. We both recalled hearing just about every song we’d hoped to hear — “Minstrel of the Dawn,” “Summer Side of Life,” “Talking In Your Sleep,” “Me and Bobby Magee,” “Did She Remember My Name” and his tour de force story-song “Canadian Railroad Trilogy.” He had a three-piece band accompanying him, and they put on a thoroughly entertaining show…

March 26, 1972: Yes, at Lakeland Community College, outside Cleveland

I had become a big fan of Yes, the British progressive rock group, due to their amazing 1971 release, “The Yes Album,” which included the hit “I’ve Seen All Good People.” Then they released the enormously popular “Fragile” LP in late 1971, and “Roundabout” become a big hit single in early 1972. My girlfriend Betsy and I jumped at the chance to see them in March of that year, even though the concert was to be held at the brand-new Lakeland Community College gymnasium about 20 miles east of Cleveland. We had to endure 15-degree weather as we waited outside for nearly two hours (again, general admission tickets), but that afforded us the opportunity to grab seats very close to the stage. It was an excellent show, with most of our favorites in the set list (“Yours is No Disgrace,” “The Clap,” “I’ve Seen All Good People,” “Roundabout,” “Long Distance Runaround,” “Heart of the Sunrise,” “America”), but the sound was so insanely loud that we suffered ringing ears for several days afterwards. This is the show that taught me to try to be more careful of how close I should sit to the loudspeakers…

April 28, 1972: Paul Simon, Joni Mitchell, and James Taylor, at Cleveland Arena

In the spring of 1972, liberal candidate George McGovern was vying for the Democratic nomination in hopes of unseating President Richard Nixon, and Hollywood celebs like Warren Beatty were actively supporting McGovern. He put together several fundraising events, one of which was scheduled in Cleveland, and to me, it seemed too good to be true: Paul Simon, Joni Mitchell and James Taylor all on the same bill! My friends and I stood in line for hours to successfully snag tickets, but it was clear from the very beginning that this would be a disappointing evening. It was held at the decaying, acoustically miserable Cleveland Arena, a hockey/boxing venue that, although it had been the site of Alan Freed’s “Moondog Coronation Ball” in 1952 (widely considered the world’s first rock concert), was well past its prime and was torn down only five years later. Simon, who had just released his solo debut LP three months earlier, played his hits (“Mother and Child Reunion” and “Me and Julio Down By the Schoolyard”) and a few Simon & Garfunkel classics, but left prematurely due to the rude, indifferent crowd. Mitchell fared even worse — her music was best suited to small halls and respectful audiences, and the Cleveland Arena crowd was apparently not there for the music. Only Taylor had much success getting through to the hob-nobbers — he was riding the success of his huge “Sweet Baby James” and “Mud Slide Slim” albums and the Top Five “Fire and Rain” and “You’ve Got a Friend” hit singles…

August 17, 1972: Bread, with Harry Chapin, at Blossom Music Center, outside Cleveland

Bread, the popular soft-rock group from LA, were at the peak of their success in the summer of ’72, thanks to multiple Top Ten hits like “Make It With You,” “It Don’t Matter to Me,” “If,” “Mother Freedom,” “Baby I’m-a Want You,” “Everything I Own,” “Diary” and “The Guitar Man.” I persuaded my former flame Jody to join me on a triple date with two other friends and their girlfriends for this second concert experience at Blossom. Harry Chapin, brand new and enjoying success with the hit “Taxi,” warmed up admirably, and Bread put on a solid, thoroughly enjoyable show, according to our collective memory. Our most vivid recollection was of my friend’s station wagon overheating as we tried to leave, which resulted in us not arriving home until nearly 3 am, to our parents’ consternation (no cell phones back then!)…

October 21, 1972: Jethro Tull, with Gentle Giant, at Public Hall, Cleveland

This was my ninth concert, but technically only my second rock show. Jethro Tull was hugely popular with the stoners and most critics, and their most recent LP at the time, “Thick as a Brick,” had, against all odds, somehow reached #1 on the charts in May 1972, despite it consisting of one 45-minute-long piece of music. The group, led by the indefatigable flautist/singer Ian Anderson, performed it that night in its entirety before also treating the crowd to several tracks from 1971’s classic “Aqualung” album (“Cross-Eyed Mary,” “Wind Up,” “Locomotive Breath”). Two friends joined me for this amazing concert, and other friends were there that night as well. Our seats, sadly, were only average, halfway back on the left side of the Public Hall auditorium. I have little memory of Gentle Giant’s opening set, but we all look back fondly on seeing Tull for the first time. They’re a visually memorable group, especially Anderson, and they went on to become one of the biggest concert draws in the world for a spell in the ’70s. I have since seen the band in concert more than two dozen times, and Anderson still releases new music as Jethro Tull today in 2025…

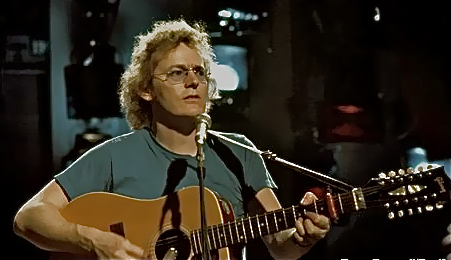

April 17, 1973: James Taylor, at Kent State University, Kent, Ohio

Kent State, famous for the polarizing National Guard shootings in May 1970, is an hour’s drive south of Cleveland, but my friend Ben and I loved James Taylor enough to make the drive down there one rainy night our senior year of high school. Taylor was late in arriving, and put on a rather muted show, which was mildly disappointing, because his most recent record, 1972’s “One Man Dog,” had plenty of additional instrumentation, including horns. But that night, it was pretty much just Taylor sitting quietly on a stool with almost no accompaniment. We certainly enjoyed it anyway, even if only because Taylor’s songs back then were so good (“Country Road,” “Long Ago and Far Away,” “Don’t Let Me Be Lonely Tonight,” “You Can Close Your Eyes”)…

April 1973: George Carlin, with Kenny Rankin, Allen Theatre, Cleveland

This almost doesn’t qualify as a music concert, because my three friends and I were there at the storied Allen Theatre to laugh at the outrageous comedy of George Carlin, who didn’t disappoint (his “Seven Words You Can’t Say on Television” was all the rage at the time). But warming up that night was label mate Kenny Rankin, an astonishingly talented singer-songwriter unknown to me at that point, but I quickly became a devotee. His song “Peaceful,” as covered by Helen Reddy, was then climbing the charts, and he wrote dozens of other wonderful songs as well. He also was adept at covering songs by The Beatles and others on albums like “Like a Seed,” “Silver Morning,” “Inside” and “The Kenny Rankin Album” throughout the ’70s…

July 10, 1973: Stephen Stills/Manassas, at Blossom Music Center, outside Cleveland

About ten of my friends and I made the spontaneous decision on this night to head out to Blossom and buy tickets at the box office (I think they were only $4 each) and party on the huge lawn that faced the outdoor amphitheater. We all knew and admired Stephen Stills for his work with Crosby, Nash and Young, but I don’t think too many of us knew much of the material he did with his erstwhile country-influenced band Manassas at the time. (I have since gone back tardily and am a big fan of the original double LP “Manassas” from 1972, which includes The Byrds’ Chris Hillman, CSNY’s Dallas Taylor and Al Perkins from The Flying Burrito Brothers, among others). I remember it was a wonderful, good-vibe kind of evening, with plenty of funny cigarettes being smoked…

Share your memories! Music matters!

****************************

The Spotify playlist includes two or three songs by each of the acts I saw at these 12 shows. I selected songs from the artists’ early catalogs that had already been released at the time of the concerts and definitely were (or might have been) part of their set lists in 1968-1973.