All alone at the end of the evening

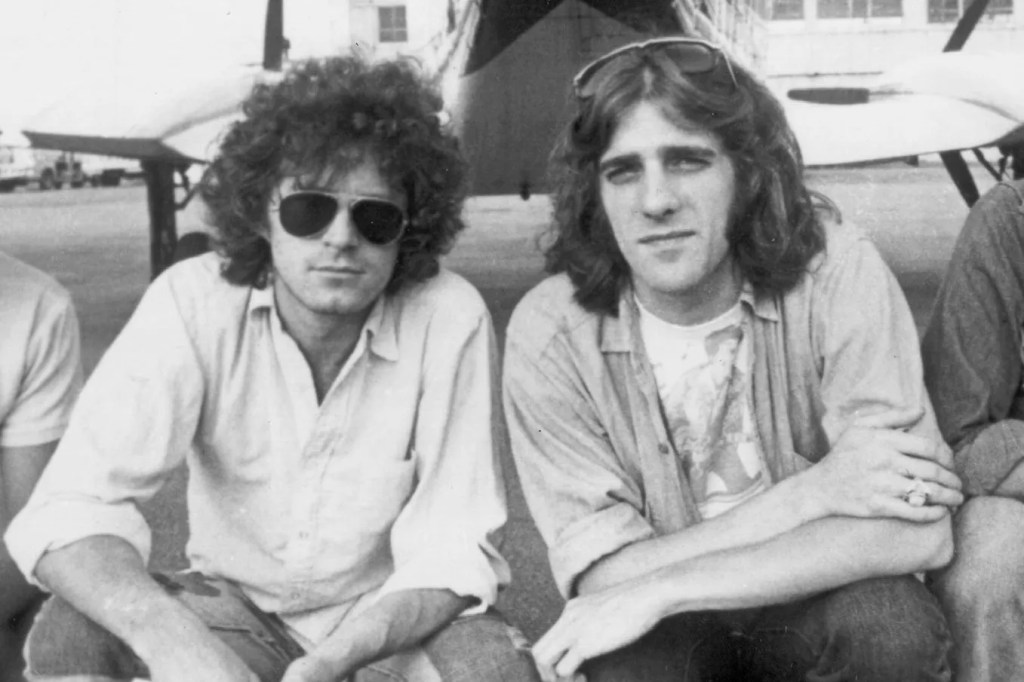

September 1977. The Eagles were on top of the world, with their multi-platinum #1 album “Hotel California,” a string of Top Five singles, and sold-out concert venues wherever they appeared. But the group’s bassist/singer didn’t really want to be there anymore and, as it turned out, the rest of the group didn’t seem to want him around anymore either.

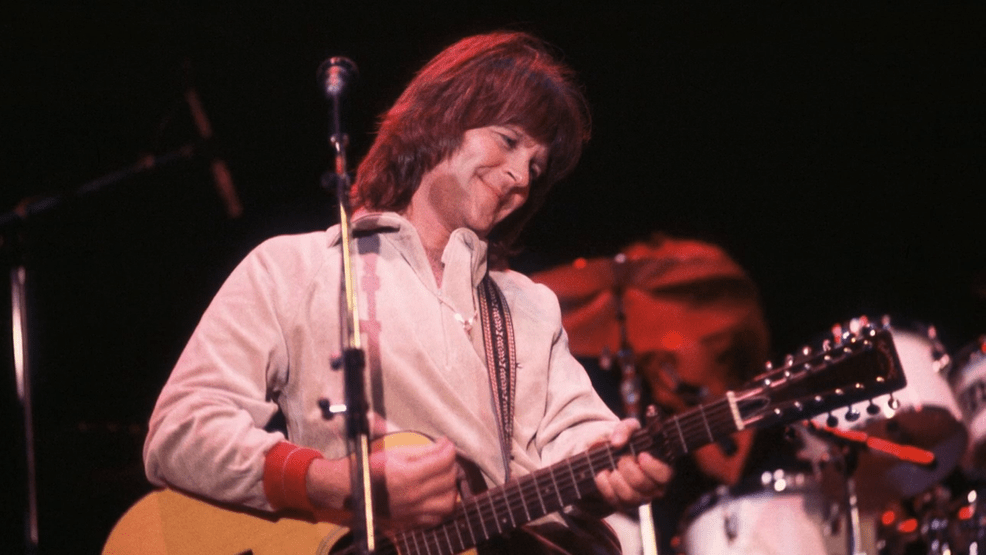

“I was always kind of shy,” said Randy Meisner, a founding member of The Eagles back in 1971, “so I didn’t like being in the spotlight. It made me uncomfortable.” That hadn’t been a problem when he was merely playing bass and adding harmonies to group vocals, but then “Take It to the Limit,” his song from the band’s 1975 LP “One Of These Nights,” became a Top Five hit and a highly anticipated part of their concert setlist, often as an encore.

Gifted with a high tenor voice, Meisner sometimes found himself dreading singing the song because it required him to hit several very high notes, and he wasn’t always confident of his ability to hit them cleanly. One night in June 1977, backstage in Knoxville, the band had already played three encores, but the crowd was screaming for more, and Glenn Frey thought they should do Meisner’s song as the final selection. Meisner refused.

Frey tried to reassure him: “It’ll be okay, you can sing it. Let’s go back out and do it.” Meisner was adamant. “No man, I’m not gonna sing the fucking song.”

Frey was livid. “You pussy!” he screamed, inches from his face. Meisner took a swing at him, and although security personnel quickly broke up the fight, the damage was done.

As Don Henley put it, “He was a hypersensitive guy, and at that point, there was always something wrong for him. ‘We’re touring too much. I’ve got to go home to my wife. I can’t take this life on the road.’ When he was feeling good and everything was right with the world, he was a great guy and fun to hang out with, and of course, he was a fine singer. But he would descend into this dark place. It got to be too much.”

The tour continued for another dozen dates, but then, as Meisner remembered, “When the tour ended, I left the band. Those last days on the road were the worst. Nobody was talking to me, or would hang out after the shows, or do anything with me. I was made an outcast of the band I’d helped start.”

Meisner, who died last week of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease at age 77, said he was glad to have been a part of The Eagles’ story, but he had grown tired and frustrated that “our tight little family had turned into a cold business.”

From many accounts, Frey and Henley, as the band’s chief songwriters and lead singers, had evolved into insufferable control freaks who insisted on calling all the shots. Making matters worse, they were overly competitive with each other and often communicated only through intermediaries. It’s not for nothing that the group was sometimes derisively referred to as The Egos.

“There was so much discontent over everything,” Meisner said, “from salaries to hotel accommodations to setlists. It got real difficult. The fact that we were all doing a lot of coke and drinking too much didn’t help. Don would get real bossy, and others would sometimes just laugh it off, but I couldn’t. I was there from the beginning and didn’t appreciate the star trip he was on.”

***********************

The “beginning” Meisner referred to was in 1971, when guitarist Frey and drummer Henley were first jamming together and ended up becoming part of Linda Ronstadt’s back-up band during her initial modest success at The Troubadour and other L.A. clubs. Frey’s R&B/rock background growing up in Detroit, and Henley’s country roots coming out of small-town Texas, provided an interesting contrast, and they were eager to form their own band.

Meisner’s own beginning goes back to a farm in Nebraska, where his parents were sharecroppers, and he fell in love with music through TV (Elvis Presley on “Ed Sullivan”) and a grandfather who played the violin. “Playing guitar and bass was the only thing I knew how to do,” said Meisner in Marc Eliot’s 1998 book “To the Limit: The Untold Story of The Eagles.” A high-school dropout who never attended college, Meisner knew that “music was the only thing for me. I taught myself scales, and chords, and put together a few bands and played at local dances.”

At a talent contest in Denver in 1964, he was invited to sit in on bass and vocals with The Soul Survivors, which turned into a bigger offer to tour with them, opening for an LA-based band called The Back Porch Majority. “We headed for the West Coast, where we all nearly starved to death. But we landed a contract with Loma Records, a subsidiary of Atlantic, and at their offices, I met and became friendly with Buffalo Springfield — Richie Furay and Steve Stills, mostly.”

The Soul Survivors struggled, bouncing back and forth between Colorado and California, eventually going through personnel changes and renaming themselves (aptly) The Poor. Meisner and The Poor eked out a meager living on the fringes of the L.A. scene until 1968, when Meisner was asked to replace Jim Messina in Buffalo Springfield. He passed the audition, but before a single gig occurred, the band dissolved, with Messina and Furay combining forces with pedal steel guitarist Rusty Young in a new band they called Poco. Meisner, along with drummer George Grantham, were brought in to round out the group.

The country rock scene was in its formative stages, with The Byrds’ “Sweetheart of the Rodeo” and Bob Dylan’s recent records leading the way. Poco relished the idea of “using country instruments and flavorings in a rock band,” as Messina once put it, and the group’s debut performance at The Troubadour in November 1968 was widely praised and led to a contract with Epic Records. Their debut LP was entitled “Pickin’ Up the Pieces,” which referred to picking up the pieces of Buffalo Springfield and starting anew.

But in an incident that presaged Meisner’s difficulties with Frey and Henley in The Eagles, Meisner found himself shut out from mixing sessions for the album, as Furay and Messina insisted on handling that responsibility themselves. Poco was their baby, and no matter how talented a bass player and backup singer Meisner was, they felt he was just a hired hand. “I said I wanted to be involved,” he recalled. “I said, ‘Hey, I’m a musician, and I played on it, too.’ They said, “No, no, we never allow anyone in when we’re mixing.’ So I said, ‘If that’s the way it is, then I don’t feel like being part of the band.’ They said okay, and that was that. I was stubborn, I guess, but felt I had the right to be there.”

On the album, released in 1969, you can hear Meisner’s bass parts and high vocals on several tracks, but his name was nowhere to be found on the credits, and they even replaced him on the cover drawing with an illustration of a dog. “I’d sung lead on a couple songs, but they took my voice off,” he noted. “I didn’t talk to those guys for nearly twenty years after that,” he said.

Meisner was replaced in Poco by another bass-playing high-tenor singer named Timothy B. Schmit. Ironically, the same personnel change would happen eight years later when Meisner left The Eagles.

Dejected and disillusioned, Meisner considered packing it in and returning to Colorado, but he was approached by none other than Rick Nelson, the former teen idol from “Ozzie and Harriet” TV fame, who had attended Poco’s Troubadour show and was forming what became the Stone Canyon Band. Meisner enthusiastically signed on and became part of the touring band for the next two years, contributing significantly to a couple of Nelson’s LPs, especially 1971’s “Rudy the Fifth.”

Meanwhile, Frey and Henley had pulled their own band together, but gigs were sporadic and the bassist quit, so they recruited Meisner, who they’d seen multiple times at The Troubadour and was, at that point, the closest of any of them to a proven rock star. The final piece of the puzzle fell into place when they signed up veteran country rocker Bernie Leadon, a multi-instrumentalist who had been with Gram Parsons in The Flying Burrito Brothers.

They chose Eagles as their name because they liked the flight imagery, the mythological connotation and the fact they were from all over America (Michigan, Texas, Nebraska and Florida). Their debut LP, recorded in England under the tutelage of veteran producer Glyn Johns, included two Top Ten hits (“Take It Easy” and “Witchy Woman”) and Meisner’s first three attempts at lead vocals — “Most of Us Are Sad,” “Take the Devil” and “Tryin’,” the latter two also written by him.

Songwriter J.D. Souther, a close friend of The Eagles in the early days and pretty much ever since, summarized the founding members’ contributions. “When they came together, they were Glenn’s band. He brought that R&B sensibility and was also a natural country singer. We used to call Don the “secret weapon,” sitting back there behind all those drums with that insanely beautiful voice. Bernie was probably the most talented musician of all of them. He could play anything — guitar, banjo, mandolin, pedal steel.

As for Meisner, Souther said, “Randy was a very important part as well. It would never have been the same band without him. His singing on the high end was unlike any other sound, and he helped define a style of songwriter-rooted bass playing. He always managed to make a nice melody under what the others were doing.”

While The Eagles’ first effort met with commercial success, their follow-up, the “cowboy outlaw” concept project called “Desperado,” did not, at least not until years later. Meisner’s contributions included “Certain Kind of Fool” and the marvelous ballad co-written with Henley, “Saturday Night.”

The band beefed up its sound and its rock-band credentials by adding guitarist Don Felder in 1974 for their third LP, “On the Border,” where Meisner’s only track was the lackluster “Is It True?” (although he sang lead on “Midnight Flyer”). The group may have been eager to be recognized as a rock band, but their first #1 single turned out to be “The Best of My Love,” a countryish original that sounded more like the material on their first album.

The evolution from country to rock continued with “One Of These Nights,” which served to frustrate Leadon’s preference for country. Despite the new album (and single) hitting #1 and establishing The Eagles as an arena-filling entity, Leadon had had enough. In the final transition from country outfit to rock band, The Eagles hired gunslinging guitar hero Joe Walsh to replace Leadon.

Meisner benefitted financially from the royalties afforded by “Take It to the Limit”‘s chart success, but as The Eagles became internationally famous, he found himself partying too much and no longer enjoying his role in the juggernaut. He wrote “Try and Love Again,” viewed by many critics as the sleeper gem on the multi-platinum “Hotel California” LP, but he was unhappy with the changing dynamics in the band’s inner workings.

Said manager Irving Azoff in Eliot’s book, “In truth, Randy had become a major pain in the ass, and I think he knew it. He was probably looking for a way to leave, and that night in Knoxville, he found it.”

After his departure from The Eagles, Meisner went on to release a half-hearted solo album (“Randy Meisner”) in 1978 that included only one original song. By 1980, he had six new tunes written for his next LP, “One More Song,” including a duet with Kim Carnes (“Deep Inside My Heart”) and his only Top 20 hit, “Hearts on Fire.” He toured with several different band lineups during the 1980s, one that included Rick Roberts of Firefall.

Meisner said he was disappointed not to be asked to participate in The Eagles 1994 “Hell Freezes Over” LP and tour, but he was pleased to be invited when the band was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1998. That evening, all seven Eagles — Frey, Henley, Meisner, Leadon, Felder, Walsh and Schmit — performed together for their one and only time, doing “Take It Easy” and “Hotel California.” Said Meisner about it: “I’d just like to say I’m honored to be here tonight. It’s just great playing with the guys again.”

Meisner developed health issues in the 2000s that brought on an early retirement from performing and recording. Last week, the end came. Felder, who had also left The Eagles under acrimonious circumstances, had this to say about his former bandmate: “Randy was one of the nicest, sweetest, most talented, and funniest guys I’ve ever known. It breaks my heart to hear of his passing. His voice stirred millions of souls, especially every time he sang ‘Take It To The Limit.’ The crowd would explode with cheers and applause. We had some wild and wicked fun memories together, brother. God bless you, Randy, for bringing so many people joy and happiness.”

I, for one, hope he can finally Rest In Peace.

*********************

The Spotify playlist I’ve assembled includes performances and/or songs Meisner contributed to Poco and Rick Nelson’s Stone Canyon Band; songs he wrote and/or on which he sang lead vocals with The Eagles, and a handful of songs from his solo albums.