A lifetime of promises, a world of dreams

My introduction to Tina Turner came in 1971, as it did for many other white suburban kids of my age, with these spoken words: “You know, every now and then, I think you might like to hear something from us nice and easy. But there’s just one thing: You see, we never ever do nothing nice and easy! We always do it nice and rough. So we’re going to take the beginning of this song and do it easy. Then we’re going to do the finish rough.”

And with that, Ike and Tina Turner launched into a slow, sensual reading of the first verse and chorus of John Fogerty’s “Proud Mary,” then abruptly segued into a frenzied double-time arrangement for the rest of the song. Holy smokes, I thought, this is way more interesting than Creedence Clearwater Revival’s ho-hum original!

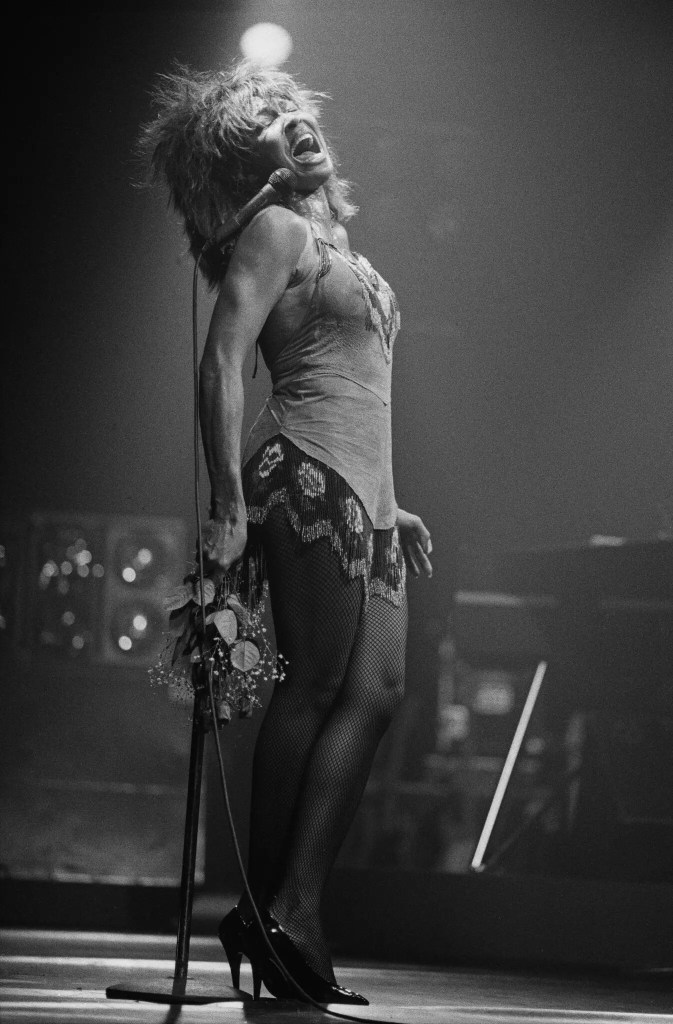

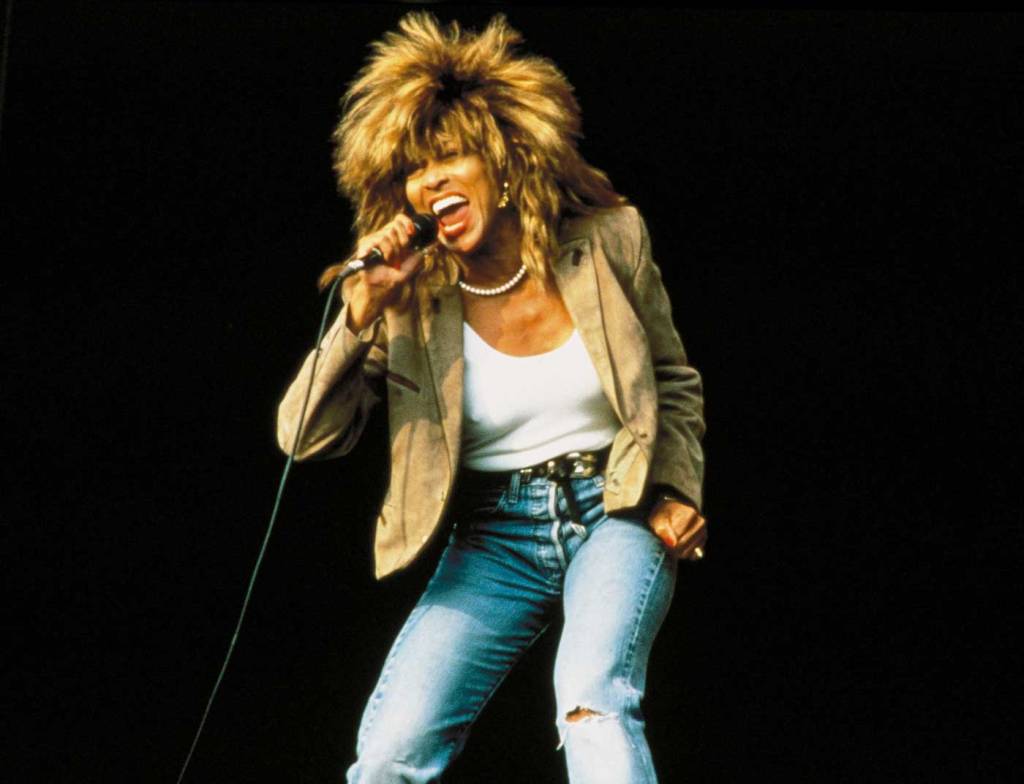

Full confession: It would take me many years before I developed a full-blown appreciation for Turner’s gifts as a one-of-a-kind entertainer. I certainly knew her big hits from the 1980s — “What’s Love Got to Do With It,” “Better Be Good to Me,” “Private Dancer,” “We Don’t Need Another Hero,” “Typical Male,” “The Best” — and her reputation as one of the most electrifying live performers to ever take a stage.

But it really wasn’t until the past week, in the wake of Turner’s death May 24 at age 83, after reading all the tributes and listening more intently to Turner’s recorded legacy, that I came to understand how much she overcame and how much she accomplished in her 50 years in show business. I strongly urge you to scroll down to the Spotify playlist at the end of this essay and hit “play.” So many superb performances!

Anna Mae Bullock was only 18 when she met and first heard Ike Turner and The Kings of Rhythm perform at a St. Louis nightclub. Turner had been a formidable guitarist and songwriter in his own right, responsible for seminal rock ‘n’ roll records like 1951’s “Rocket 88,” and he knew how to present a riveting live act. But one night in 1957 during a break, the petite girl who longed to be on stage got her chance, belting out B.B. King’s “You Know I Love You,” and Turner was gobsmacked. “I would write songs with Little Richard in mind,” said Turner in his 1999 autobiography, “but I didn’t have no Little Richard to sing them. Once I heard Tina, she became my Little Richard. Listen closely to Tina and who do you hear? Little Richard singing in the female voice.”

Her potent, bluesy singing and supercharged dancing style soon made her the group’s star attraction, and Turner’s wife. The ensemble was renamed The Ike and Tina Turner Revue and became one of the premier touring soul acts of the early-to-mid-1960s in R&B venues on what was then called “the chitlin’ circuit.” Their work wasn’t yet embraced by mainstream audiences, but if you pay close attention to the first dozen tracks selected for the playlist (especially “A Fool in Love,” “Cussin’, Cryin’ and Carryin’ On” and the Phil Spector-produced “River Deep, Mountain High”), you’ll be reminded (or discover) what all the fuss was about.

Over in England, The Rolling Stones invited the group to open for them, first on a British tour in 1966 and then on an American tour in 1969, which caused rock audiences in both countries to sit up and take notice. (You could make a strong case that Mick Jagger was deeply influenced by Tina Turner’s stage presence as he developed his own in-concert persona.)

I’m reluctant to mention too much about the horrible abuse and violence Tina endured at the hands of her first husband, particularly once he developed a cocaine addiction and an irrational jealousy of her ever-increasing time in the spotlight. Suffice it to say that she suffered indignities and injuries that hurt her self-esteem and her career for many years in the ’60s and ’70s, and she deserves a huge amount of credit for eventually breaking free from his suffocating control.

“It’s very difficult to explain to people why I stayed as long as I did,” she said many years later. “I’d left Tennessee as a little country girl and stepped into a man’s life who was a producer and had money and was a star in his own right. At one time, Ike Turner had been very nice to me, but later he changed to become a horrible person.”

Desperate to be rid of him, she agreed to divorce terms that left her virtually penniless. She gave Ike nearly all their money and the publishing royalties for her compositions. “You take everything I’ve made in the last sixteen years,” she said. “I’ll take my future.”

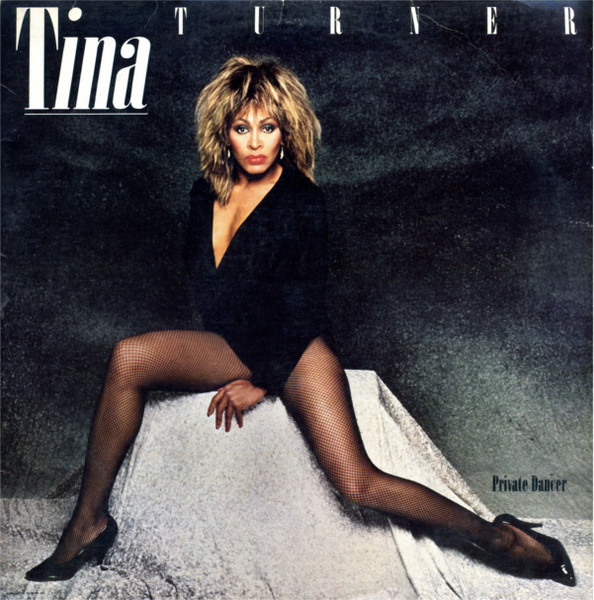

Turner’s solo career was slow to take off. Her first few albums didn’t sell, her record label dropped her, and she was back to playing small clubs and in ill-advised cabaret acts for a time. When Olivia Newton-John’s manager, Roger Davies, began guiding her in 1980, Turner readopted the gritty, hard-rocking style that had made her a crossover star, which led to a startling cover version of The Temptations’ “Ball of Confusion” on an album of rock and soul covers called British Electric Foundation. That in turn led to a stupendous remake of Al Green’s “Let’s Stay Together,” which reached #26 on US pop charts in 1983. That success attracted Capitol Records, who approved an album with the caveat that it be recorded and released in less than a month.

A number of prominent songwriters and producers — Rupert Hine, Mark Knopfler, Ann Peebles, Terry Britten — came forward to offer their songs and their services, and the result was “Private Dancer,” one of the biggest albums of 1984 and, indeed, of the 1980s, selling upwards of 10 million copies worldwide. The LP was described by one critic as “innovative fusion of old-fashioned soul singing and new wave synth-pop.” Seven tracks were released as singles in either the US or the UK, with “What’s Love Got to Do With It,” “Better Be Good to Me” and “Private Dancer” all reaching the Top Ten here.

At age 44, Turner had finally attained the superstardom she’d dreamed of since first stepping on stage. Four more albums over the next 15 years achieved platinum status (especially the 1986 follow-up “Break Every Rule,” which reached #4), and she cemented her reputation as one of the top concert draws in the world. She also showed her chops in film, playing the ruthless Aunty Entity in the 1985 blockbuster dystopian action hit “Mad Max Beyond Thunderdome,” which spawned another #1 hit, “We Don’t Need Another Hero.”

One of the things I most admire about Turner is her ability and willingness to record covers of popular R&B songs and rock tunes with equal flair. Check out some of the titles you’ll find in her catalog: “Come Together” and “Get Back” (The Beatles), “Living For the City” (Stevie Wonder), “In the Midnight Hour” (Wilson Pickett), “Reconsider Baby” (Elvis Presley), “The Acid Queen” (The Who). I’m even more impressed by the number of major rock stars who have partnered with Turner on various duet projects over the years: Eric Clapton (“Tearing Us Apart”), Rod Stewart (“It Takes Two”), Bono (“Theme from ‘Goldeneye'”), Bryan Adams (“It’s Only Love”), David Bowie (“Let’s Dance”).

Her tempestuous first marriage provided much of the material for the 1993 film “What’s Love Got to Do With It,” with Angela Bassett and Laurence Fishburne in the lead roles. Turner re-recorded some of her hits, and one new song, “I Don’t Want to Fight,” but otherwise declined to participate. “Why would I want to see Ike Turner beat me up again?” she said at the time.

The best indication of how much respect artists have earned is the number of major players who praise them, both in life and in death. “How do we say farewell to a woman who owned her pain and trauma and used it as a means to help change the world?” Bassett said last week. “Through her courage in telling her story, and her determination to carve out a space in rock and roll for herself and for others who look like her, Tina Turner showed others who lived in fear what a beautiful future filled with love, compassion, and freedom could look like.”

Beyoncé, arguably the most popular singer on the planet at the moment, said, “My beloved queen. I love you endlessly. I’m so grateful for your inspiration and all the ways you have paved the way. You are strength and resilience. You are the epitome of power and passion. We are all so fortunate to have witnessed your kindness and beautiful spirit.”

The Who’s Pete Townshend, who had suggested Turner for the part of The Acid Queen in the 1975 film version of “Tommy,” described her as “an astonishing performer, an astounding singer, an R&B groundbreaker. If you ever had the privilege of seeing Tina perform live, you will know how utterly scary she could be. She was an immense presence. She was, of course, my Acid Queen in the ‘Tommy’ movie, and it is often my job to sing that song with The Who, so she always comes to mind, which isn’t easy to deal with. The song is about abuse at the hands of an evil woman. How she turned that song on its head! All the anger of her years as a victim exploded into fire, and bluster, and a magnificent and crazy cameo role that will always stay with me.”

The multi-talented Oprah Winfrey noted, “I started out as a fan of Tina Turner, then a full-on groupie, following her from show to show around the country, and then, eventually, we became real friends. She contained a magnitude of inner strength that grew throughout her life. She was a role model not only for me but for the world. She encouraged a part of me I didn’t know existed.”

The time Winfrey was invited on stage in Los Angeles to dance with Turner “was the most fun I ever had stepping out of my box. Tina lived out of the box and encouraged me and every woman to do the same.”

The industry has given Turner many accolades. Twice she was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame (with Ike in 1991 and on her own in 2021); she received a Kennedy Center Honor in 2005 and a Grammy lifetime achievement award in 2018.

Rest in peace, Tina. Your place in music history is iron-clad secure.

*************************