Telling my whole life with (her) words

“She sang reveries as much as exclamations, and yet her stillness electrified the soul. In time, the style she created became known as ‘quiet storm.’ If she was unlike singers who came before her, there were many who would emulate her in her wake.”

This was one of many praiseworthy comments written about singer Roberta Flack over the past few days following her death February 24th at age 88.

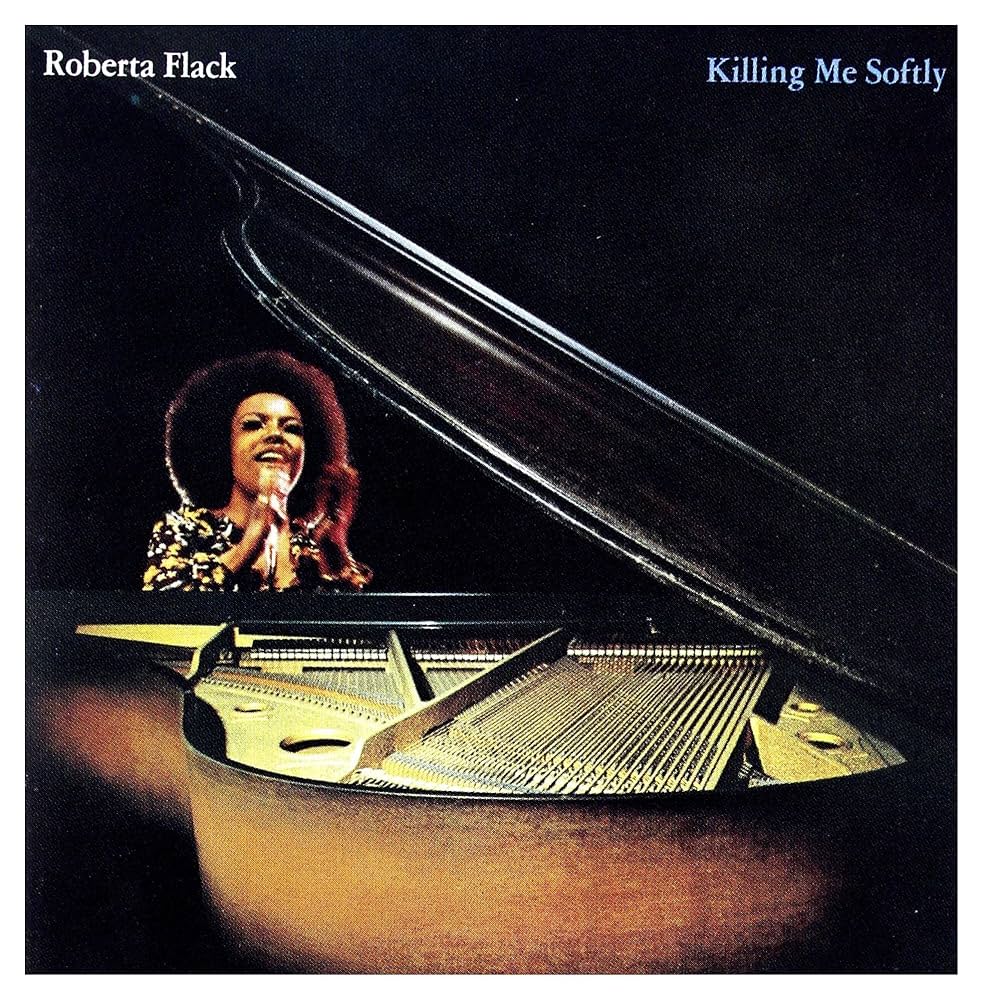

Although her first LP came out back in 1969 and I’d been hearing her name for a couple of years, my initial impression of Flack didn’t come until early 1973 when she released the indelible single “Killing Me Softly With His Song.” It may have leaned a bit too much toward middle-of-the-road pop for my rock ‘n’ roll/blues tastes, but it nevertheless grabbed me, thanks to the compelling lyrics and her flawless vocal delivery. Mainstream listeners went wild for it, sending the song to #1 on the US pop charts and in Canada and Australia, and into the Top Ten in six other countries. The following March, Flack’s recording landed the coveted Record of the Year honors as well.

A native of Asheville, NC, Flack proved to be a piano prodigy, playing alongside the choir at her church and going on to earn a scholarship to study classical music at Howard University. For Flack, classical music was the foundation of her practice; even the music at the church her family attended was more Handel and Bach than the high-energy gospel found in Baptist churches. “For the first three decades of my life, I lived in the world of classical music,” Flack said. “There were these wonderful melodies and harmonies that were the vehicles through which I could express myself.”

David Nathan, soul music historian and author, wrote, “Roberta was a towering force as a musician and singer. One of her greatest gifts was her ability to find songs that really expressed emotion. When you listen to Roberta, you hear different elements of her classical training; her approach to a whole diversity of music that was unlike anyone else’s. Listen to some of her greatest recordings, and you hear singing and playing that’s measured and thoughtful, and still has all the emotion in it. She didn’t like it when people categorized her as either R&B, soul or pop. The truth is she was all of it.”

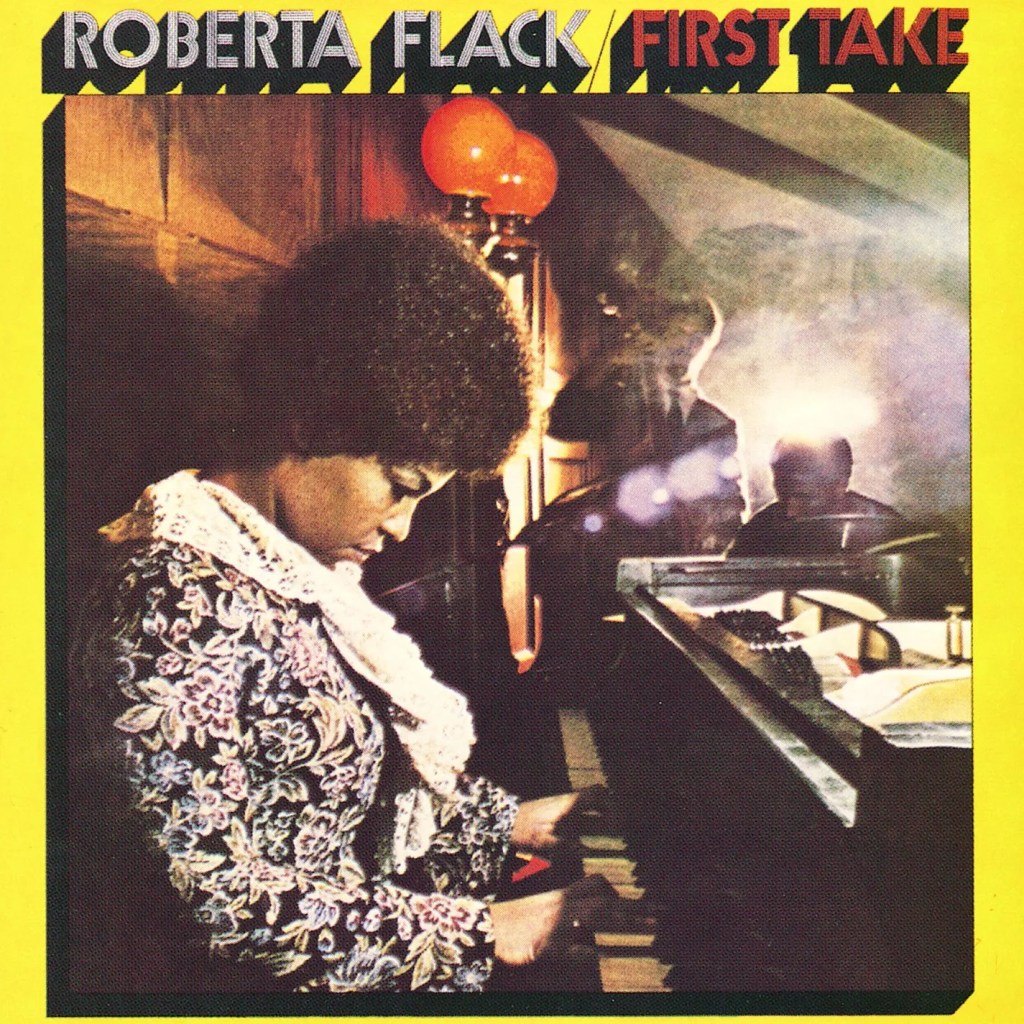

After graduating from Howard, she started a teaching career, and eventually began gigging in clubs in Washington, D.C. As the buzz around her grew, she was signed to Atlantic Records, which released her debut, “First Take,” in 1969. That album showed Flack interpreting an array of different songs, from the classic jazz/blues protest “Compared to What” to what is arguably the definitive version of Leonard Cohen’s sensitive “Hey, That’s No Way to Say Goodbye.”

While “First Take” would eventually assume its rightful place as a widely recognized masterpiece, success was not immediate. The first few singles failed to chart, and Flack quickly moved on to her next records, releasing “Chapter Two” in 1970 and “Quiet Fire” in 1971. She also linked up with friend and fellow Howard University student Donny Hathaway for a duets album, with the pair earning minor hits with contemporary pop standards like “You’ve Lost That Lovin’ Feelin'” and “You’ve Got a Friend.”

But Flack’s real breakthrough came when Clint Eastwood used her meditative version of British folksinger Ewan MacColl’s “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face” — originally recorded for “First Take” — in “Play Misty For Me,” his 1971 thriller about a jazz radio DJ. The song shot to #1, with the album eventually reaching #1 as well in April 1972, nearly three years after its original release.

Flack’s version of “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face” would go on to win the Grammy for Record of the Year in 1973, and she and Hathaway won a Best Duo Pop Vocal Performance for “Where Is the Love” that year as well.

In the summer of 1972, Flack said she first heard “Killing Me Softly With His Song” on an airplane when the original version by the relatively unknown singer Lori Lieberman was featured on the in-flight audio program. “The title, of course, smacked me in the face,” Flack recalled in the 1990s. “I immediately pulled out some scratch paper, played the song at least eight to ten times jotting down the melody that I heard. When I landed, I immediately had my manager contact the songwriters. Two days later, I had the music, and recorded it shortly thereafter.”

(A bit of trivia: Most people probably aren’t aware that “his song” — the one that’s referred to in the title — is “Empty Chairs” by Don McLean, which Lieberman had heard the singer perform at a club in 1972. She was so moved by it that she grabbed a cocktail napkin and scribbled, “He’s killing me softly with this song.” She passed that along to her manager/producer duo, Norman Gimbel and Charles Fox, who fleshed it out into the completed piece.)

When it won Flack’s second consecutive Record of the Year Grammy, it was the only time an artist had won back-to-back Grammys in that important category (until U2 duplicated the feat in 2001-2002).

Also on the “Killing Me Softly” album was her rendition of Janis Ian’s song “Jesse,” which stalled at #30 on pop charts but reached #3 on the adult contemporary chart. Said Ian, “One day, I learned that Roberta had fallen in love with my demo of “Jesse” and wanted to record it. She said it was a no-brainer that she’d record it but it might take a while. I cannot begin to tell you what that meant to me. It was released on the heels ‘Killing Me Softly,’ and suddenly I was worthy of respect again. I owe her more than I can possibly say.”

Flack scored her third #1 single the following year with the sunny “Feel Like Makin’ Love.” With Hathaway again in 1978, she recorded the romantic ballad “The Closer I Get to You,” written by two of Miles Davis’s sidemen, James Mtume and Reggie Lucas, reaching #2 on pop charts.

While Flack helped pioneer the “quiet storm” genre, her versatility as a performer and interpreter incorporated elements of folk, rock, jazz, R&B, show tunes, and soul. “My music is inspired thought by thought, and feeling by feeling, not note by note,” she once said. “I tell my own story in each song as honestly as I can in the hope that each person can hear it and feel their own story within those feelings.”

Not every critic embraced Flack’s music. Notoriously prickly Village Voice critic Robert Christgau once wrote, “Flack has nothing whatsoever to do with rock and roll or rhythm and blues, and almost nothing to do with soul. Her middle-of-the-road aesthetic is like Barry Manilow but with better taste.”

But Rolling Stone writer Mikal Gilmore took a different view. “Her influence has never stopped reverberating. Flack was a woman who sang in a measured voice, but her measurements moved times and events as much as they moved hearts.” Critic Steve Huey called Flack’s music “classy, urbane, reserved, smooth, and sophisticated. She generated rapturous, spellbinding mood music that plumbed the depths of soulful heaviness by way of classically-informed technique.”

In the 1980s and 1990s, Flack’s chart successes began to wane but still included such notable tracks as “Tonight, I Celebrate My Love” with Peabo Bryson, 1988’s “Oasis” and 1991’s “Set the Night to Music. Flack released her last full-length record, “Let It Be Roberta” — a collection of her renditions of Beatles songs — in 2012. She was honored with a Lifetime Achievement Award in 2020. “It was overwhelming,” she said. “When I met those artists and so many others in person and heard from them that they were inspired by my music, I felt understood.”

Flack was also deeply involved in political movements of the post-Civil Rights era. She befriended Angela Davis and the Rev. Jesse Jackson, and she sang at Bob Dylan’s 1975 benefit concert for boxer Rubin “Hurricane” Carter, who’d been wrongfully convicted of murder. She was also a staunch supporter of gay rights, and was an active member of the Artist Empowerment Coalition, which advocates for artists to have the right to control their creative properties. Her involvement in ASPCA included an appearance in a commercial showing animal faces with “The First Time Ever I Saw Your Face” playing behind them

She lent her name and financial backing to The Hyde Leadership Charter School in the Bronx, which ran an after-school music program called “The Roberta Flack School of Music” to provide free music education to underprivileged students.

In 2022, Flack was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and lost her ability to sing. The disease, her rep said at the time, “has made it impossible to sing and not easy to speak.”

John Lennon’s son Sean publicly mourned the singer, pointing out that she lived for a while in The Dakota in Manhattan down the hall from their late father. “We’d call her Aunt Roberta,” said Sean. “She was a close family friend, incredibly kind and uniquely talented. I’m so grateful to have known her.”

Rest In Peace, Roberta.

*********************