Let me live in your blue heaven when I die

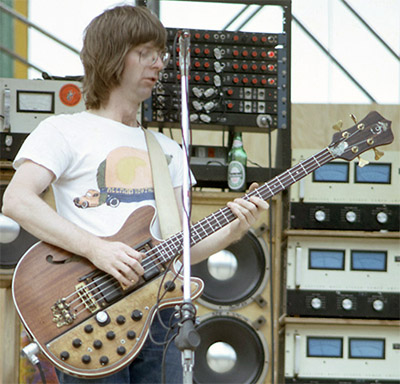

Apologies to bass players everywhere, but the average music fan doesn’t give much thought to you and what you might provide to a band’s sound. Singers, guitarists, keyboard players, sax players, even drummers all seem to get more attention than the guy or gal off to the side who dutifully plays that four-stringed instrument.

There are exceptions — extraordinary bassists like Paul McCartney, James Jameson of Motown’s “Funk Brothers” house band, John Entwistle of The Who, Jack Bruce of Cream, Carol Kane of LA’s “The Wrecking Crew”, Chris Squire of Yes — but even these virtuosos’ names aren’t necessarily familiar to casual rock music followers.

I’m NOT a casual follower. I’m more of an obsessed fanatic who has been accused of having encyclopedic knowledge of classic rock music and its players. And yet, I concede I’m guilty of not having mentioned the name of Phil Lesh when I’ve listed the top-flight bass players of his age.

Lesh, who died last week at age 84, anchored The Grateful Dead from inception to dissolution, a 30-year span in which he participated in 14 studio albums, eight live albums and somewhere in the neighborhood of 2,300 concerts. That in itself is a monumental achievement but, because I was never what you’d call a huge Dead fan, I wasn’t really aware until after his death how influential, how imaginative, how remarkable his bass playing was.

As Jim Farber put it The New York Times: “Lesh’s bass work could be thundering or tender, focused or abstract. On the Grateful Dead’s studio albums, his lines held so much melody that one could listen to a song just for his playing alone. At the same time, he shared his bandmates’ love for unusual chord structures and uncommon time signatures. In constructing his bass parts, he drew from many sources, including free jazz, classical music and the avant-garde.”

Unique among rock bass players was Lesh’s background as a classical violinist and trumpeter, an orchestral composer and student of avant-garde musical genres in the years preceding his joining the original lineup of The Warlocks, the band Jerry Garcia founded from which The Grateful Dead was born. Lesh had never played a bass before but told Garcia he wanted to learn it. Said Lesh years later, “It never really mattered to me very much what instrument I was playing, so long as I could make some music.”

It was his lack of experience with the instrument that allowed him to reimagine its role in rock music, drawing inspiration from the harmonics present in works he admired by Bach and the jazz bassist Charles Mingus. It was this unique montage of influences, Lesh wrote in his autobiography, that resulted in the sound that he and the Dead devised as “not rock, jazz or blues, but some kind of genre-busting rainbow polka-dot hybrid mutation.”

Lesh used the bass to provide continually evolving counterpoints to Garcia’s ethereal lead guitar lines, as well as the forceful chords of rhythm guitarist Bob Weir, the dynamic synchonicity of drummers Mickey Hart and Bill Kreutzmann, and the appealing keyboards of Ron “Pigpen” McKernan (until his death in 1973). In particular, the exciting interplay between Garcia and Lesh was probably the band’s most important feature. The two men complemented and contrasted each other’s styles to such a degree that they could go off on lengthy improvisations with little risk of alienating listeners.

Last week, Weir offered this summary of Lesh’s influence on his and the band’s development: “Phil turned me on to the John Coltrane Quartet, and the wonders of modern classical music with its textures and developments, which we soon tried our hands at incorporating into what we had to offer. This was all new to most peoples’ ears.”

Indeed, Lesh’s work with the Dead was held in such high regard by the fan base that his most ardent followers would often position themselves at concerts in an area that became known as “the Phil Zone,” in order to better see and hear what he was bringing to the overall sound.

Lesh also chipped in some of the backing vocals to the multi-voice harmonies the Dead showcased. More important, he made major songwriting contributions to the group’s catalog, writing or co-writing such iconic tracks as “Truckin’,” “St. Stephen,” “Cumberland Blues,” “Box of Rain” and “Unbroken Chain,” the last of which also featured Lesh on lead vocals.

While I admired their musical chops and what they were able to achieve in their three decades in the business, I would say I’ve been no more than a modest fan of The Dead over the years. I own the two marvelous LPs from 1970, “Workingman’s Dead” and “American Beauty”; the awesome triple album, “Europe ’72”; and their surprising commercial comeback in 1987, “In the Dark.” But if I were to list my favorite rock artists, The Dead wouldn’t make my Top 30.

Part of the reason, I think, is that I felt like I wasn’t really part of the one-of-a-kind bond the band shared with its core audience. I felt like an outsider, even though I was sympathetic to the sweet devotion, sharing and general kindness that were the hallmarks of the relationship between the band and its fans, who are lovingly referred to as Deadheads. I feel as if I missed that era.

Lesh noted, “An article in a music magazine once stated, ‘The real medium of rock and roll is records. Concerts are only repeats of records.’ The Dead represent the opposite of that idea. Our records are definitely not it. The concerts are it, but we’re not in such total control of our scene that we can say, ‘Tonight’s the night, it’s going to be magic tonight.’ We can only say we’re going to try it again tonight. Each night was like jumping off a cliff together.”

Still, Lesh said he was incredulous when the band made the seismic shift from jam band in 1969 to a purveyor of conventional length songs with pleasant melodies and engaging harmonies. “The almost miraculous appearance of these new songs on ‘Workingman’s Dead’ and ‘American Beauty’ would also generate a massive paradigm shift in our group mind: from the mind-munching frenzy of a seven-headed fire-breathing dragon to the warmth and serenity of a choir of chanting cherubim. Personally, I was thrilled that the band could make such a complete musical about-face while still maintaining the flat-out weirdness that I’d come to know and love.”

As the story goes, the name Grateful Dead happened serendipitously when Garcia opened a big book and saw the two words positioned opposite each other on facing pages. It turned out the phrase had a deeper meaning: It refers to folk tales in which “a dead person, or his angel, shows gratitude to someone who, as an act of charity, arranged for their proper burial.” They found this act of kindness in keeping with their overarching spirit of community. Stumbling on that phrase in a book was just the sort of cosmic randomness that fascinated the group, and it came to dominate how the band would exist throughout its lifetime. “Every night that we went out on stage, you never knew what might happen,” said Lesh. “We rarely had a prepared set list. We just played what felt right at that moment. I just loved that about us.”

Lesh compared the Grateful Dead’s music to life itself. Both, he said, were “a series of recurring themes, transpositions, repetitions, unexpected developments, all converging to define form that is not necessarily apparent until its ending has come and gone.”

In 1994, a year before Garcia’s death brought the band to its end, The Dead were inducted into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Lesh played in the offshoot bands the Other Ones, the Dead and Furthur, as well as with his own assemblage, Phil Lesh and Friends, releasing the surprisingly strong “There and Back Again” in 2002 (a few tracks are included on the Spotify playlist below). He retired from regular road work in 2014 following a series of health challenges, including a liver transplant, prostate cancer and bladder cancer, and back surgery.

“I would have to say that music and performing are as essential as food and drink to me, but even more so as I get older,” he said in 2005. “While it can sometimes be more of a challenge physically than it was when I was a young whippersnapper, I’ve found that age brings wisdom, and with that comes musical experience and knowledge that I didn’t have when I was younger.”

Added Weir, “Phil wasn’t particularly averse to ruffling a few feathers. We had our differences, of course, but it only made our work together more meaningful. Given that death is the last and best reward for ‘a life well and fully lived,’ I rejoice in his liberation.”

R.I.P., Mr. Lesh. You can be proud of the music and life experiences you shared with the world.

*************************