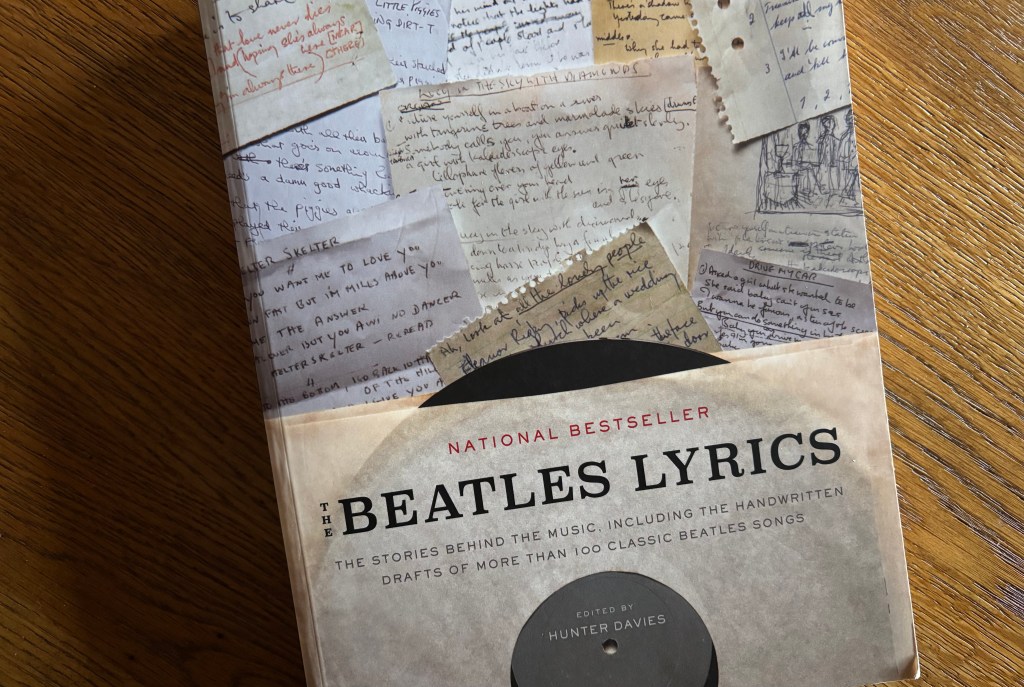

It’s a thousand pages, give or take a few

If you’re trying to come out of your holiday fog, I think I’ve got just the thing to get your brain revved up for the New Year.

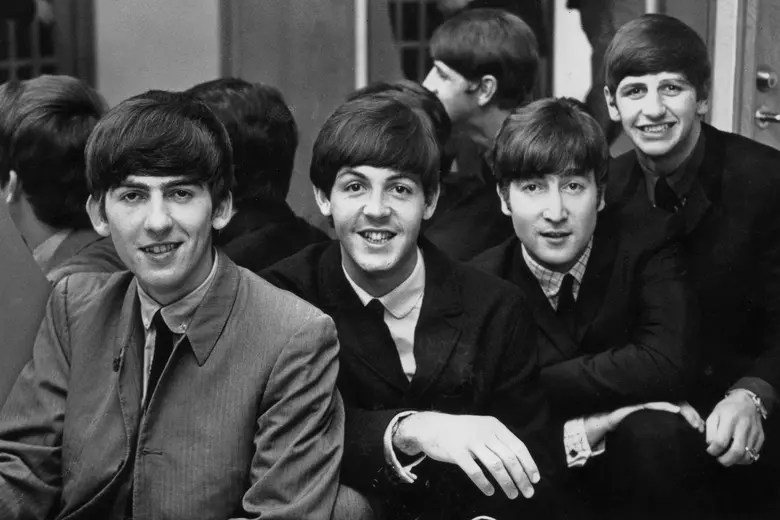

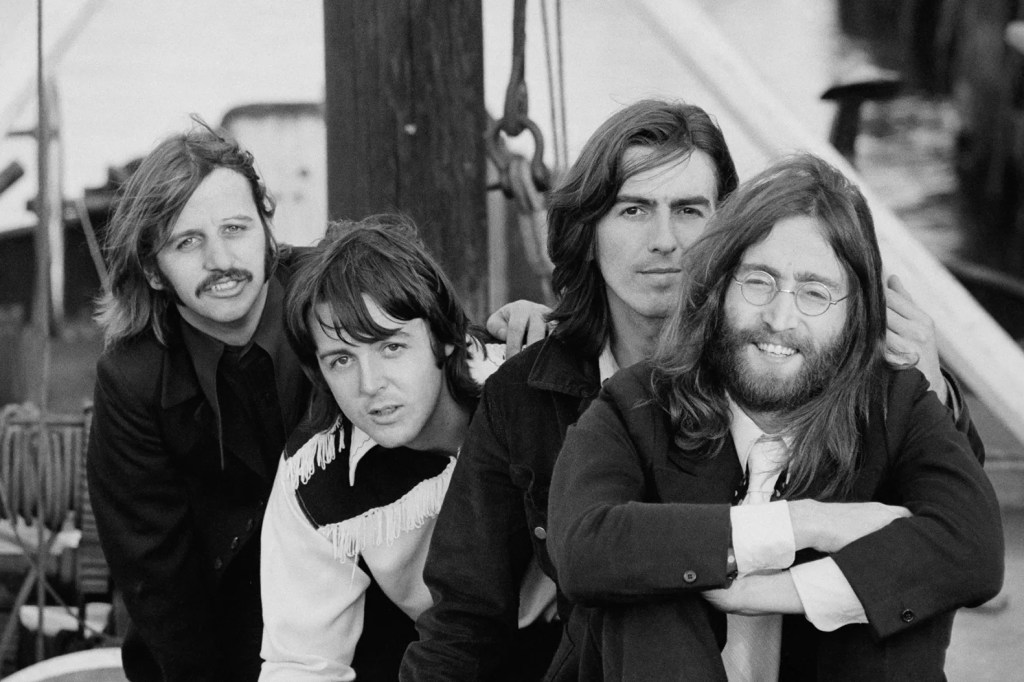

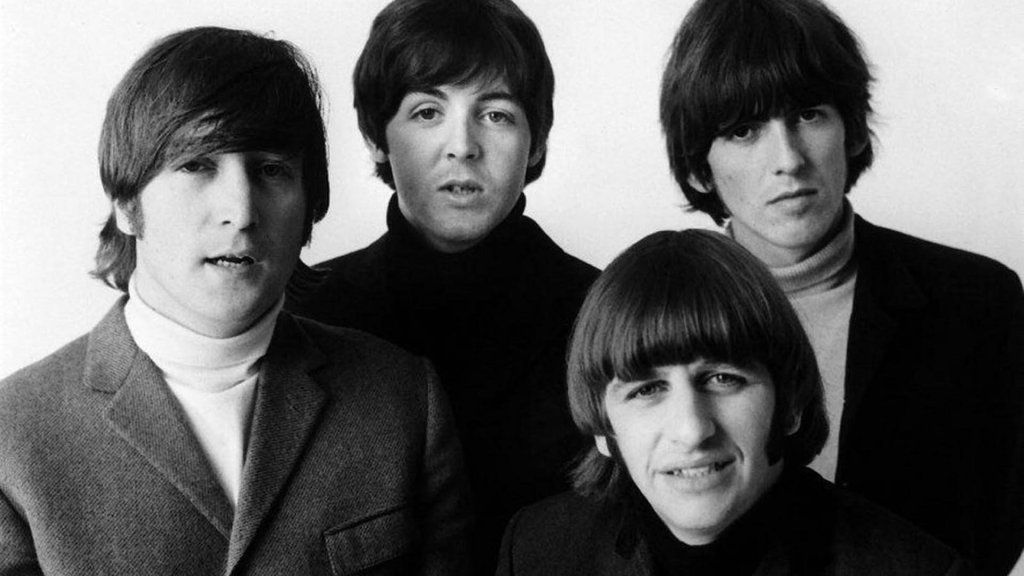

I’m offering a Rock Lyrics Quiz that focuses on The Beatles, which is still probably the most recognizable catalog in pop music history.

It won’t be as easy as it sounds, though. While the roughly 220 songs they recorded include a few dozen widely recognized hits, there were also plenty of album tracks that got less exposure and are therefore more difficult to pick out. So I’ve divided the quiz into three sections — easy, intermediate, and difficult.

I administered the quiz to my wife (who loves the Beatles’ music but I wouldn’t call her a fanatic), and she scored about as I expected she would: She aced the easy lyrics, did fairly well on the intermediate group and struggled with the difficult ones. She said it would have been far easier to recognize the lyrics if she heard them sung as opposed to reading them on a printed page or computer screen, and I’ll bet many readers will feel the same.

In any event, here’s how I suggest you play: Grab a pencil and paper and jot down your answers as you proceed. When you’re done, simply scroll down to find the correct answers — no peeking! I’ve written a little bit about each song, and there’s the usual Spotify playlist at the end to hear the tunes after the fact.

It’s a good mental exercise to try to recall rock music lyrics. It just might clear your head and test your memory bank, which we all need now and then. Enjoy!

******************

EASY

1 “Remember to let her into your heart, then you can start to make it better…”

2 “Well, my heart went ‘boom’ when I crossed that room, and I held her hand in mine…”

3 “He say, ‘I know you, you know me,’ one thing I can tell you is you got to be free…”

4 “I’ll pretend that I’m kissing the lips I am missing…”

5 “Many times I’ve been alone, and many times I’ve cried…”

6 “Say you don’t need no diamond rings and I’ll be satisfied…”

7 “I look at the floor, and I see it needs sweeping…”

8 “All these places had their moments with lovers and friends I still can recall…”

9 “Look at him working, darning his socks in the night when there’s nobody there…”

10 “Baby says she’s mine, you know, she tells me all the time, you know, she said so…”

11 “Why she had to go, I don’t know, she wouldn’t say…”

12 “Nothing you can say, but you can learn how to play the game, it’s easy…”

INTERMEDIATE

13 “Newspaper taxis appear on the shore, waiting to take you away…”

14 “You don’t need me to show the way, love, why do I always have to say, love…”

15 “If looks could kill, it would’ve been us instead of him…”

16 “I’m taking the time for a number of things that weren’t important yesterday…”

17 “But ’til she’s here, please don’t come near, just stay away…”

18 “‘Cause I couldn’t stand the pain, and I would be sad if our new love was in vain…”

19 “Soon we’ll be away from here, step on the gas and wipe that tear away…”

20 “When you say she’s looking good, she acts as if it’s understood, she’s cool…”

21 “Then we’d lie beneath the shady tree, I love her and she’s loving me…”

22 “Boy, you’ve been a naughty girl, you let your knickers down…”

23 “Gather ’round, all you clowns, let me hear you say…”

24 “Sweet Loretta Martin thought she was a woman, but she was another man…”

DIFFICULT

25 “‘We’ll be over soon,’ they said, now they’ve lost themselves instead…”

26 “In my mind, there’s no sorrow, don’t you know that it’s so?…”

27 “Everybody pulled their socks up, everybody put their foot down, oh yeah…”

28 “You’re giving me the same old line, I’m wondering why…”

29 “But listen to the color of your dreams, it is not living, it is not living…”

30 “I know it’s true, it’s all because of you, and if I make it through, it’s all because of you…”

31 “You could find better things to do than to break my heart again…”

32 “Tell me, tell me, tell me the answer, you may be a lover but you ain’t no dancer…”

33 “Had you come some other day, then it might not have been like this…”

34 “Waiting to keep the appointment she made, meeting a man from the motor trade…”

35 “Don’t you know I can’t take it, I don’t know who can, I’m not going to make it…”

36 “The men from the press said, ‘We wish you success, it’s good to have the both of you back…'”

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

*

**************************

Answers:

EASY

1 “Remember to let her into your heart, then you can start to make it better…”

“Hey Jude” (single, 1968)

This tune, their biggest-selling song ever, got its start as “Hey Jules,” Paul McCartney’s song of support for a young Julian Lennon, who was coping with his parents’ divorce in 1968. John Lennon interpreted the lyrics as a message to him and Yoko (“You have found her, now go and get her”). It became a singalong anthem for the ages.

2 “Well, my heart went ‘boom’ when I crossed that room, and I held her hand in mine…”

“I Saw Her Standing There” (from “Please Please Me” LP, 1963)

The Beatles’ set list during their formative years playing clubs in London and Hamburg was full of vintage tunes by Chuck Berry, Buddy Holly and Little Richard, but the first track on the band’s debut LP was an authentic rocker original written by McCartney and fine-tuned by Lennon. It’s every bit as valid an entry in the rock ‘n’ roll canon as “Long Tally Sally” or “Roll Over Beethoven.”

3 “He say, ‘I know you, you know me,’ one thing I can tell you is you got to be free…”

“Come Together” (from “Abbey Road” LP, 1969)

When Lennon was asked to write a song for LSD maven Timothy Leary’s ill-fated campaign for the California governorship, all he came up with was a chant using the slogan “Come together, join the party.” Lennon later created some whimsically enigmatic wordplay (“ju-ju eyeball,” “mojo filter”) and set it to a funky, bluesy tempo that became a #1 single and one of Lennon’s favorite Beatles tunes.

4 “I’ll pretend that I’m kissing the lips I am missing…”

“All My Loving” (from “With the Beatles,” 1963)

When millions of Americans got their first glimpse of The Beatles as they performed for the first time on “The Ed Sullivan Show” in February 1964, this is the first song the band played. It’s an infectious McCartney melody with simple lyrics about sending loving thoughts home to his girl while he’s away. It’s one of the better examples of the band’s innocent early songs, and would have made a terrific single.

5 “Many times I’ve been alone, and many times I’ve cried…”

“The Long and Winding Road” (from “Let It Be” LP, 1970)

Because this McCartney ballad was released in 1970 just as the group’s break-up was announced, it’s tinged with sadness and regret. Although it was written more than a year earlier, the song’s lyrics portend the separation and estrangement that was on the horizon (“You left me standing here a long long time ago”). It was the final Beatles single in the US until “Free As a Bird” 25 years later.

6 “Say you don’t need no diamond rings and I’ll be satisfied…”

“Can’t Buy Me Love” (from “A Hard Day’s Night” LP, 1964)

Producer George Martin correctly suggested the group begin this song with the catchy chorus instead of the first verse, and that helped instantly grab the attention of radio listeners much as “She Loves You” had done. It became a linchpin song on the soundtrack of their madcap debut film “A Hard Day’s Night,” accompanying a sequence where the boys ran and jumped around an open courtyard to let off steam.

7 “I look at the floor, and I see it needs sweeping…”

“While My Guitar Gently Weeps” (from “The White Album” LP, 1968)

George Harrison, motivated by the “relativism” taught in Eastern literature, decided to write a song based on the first words he saw upon opening a book. Those words were “gently weeps,” and he chose to use them to describe the sound of an electric guitar. His friend Eric Clapton famously played the solo (uncredited at the time), and the track ignited a prolific period of quality songwriting for Harrison.

8 “All these places had their moments with lovers and friends I still can recall…”

“In My Life” (from “Rubber Soul” LP, 1965)

Lennon always maintained he wrote the bulk of this song of tender reflection, but McCartney claims he wrote “at least half” of the words. Regardless, the tune has become one of the most popular non-singles they ever wrote, and because of its lyrics of remembrance and affection (“Some are dead and some are living, /In my life, I’ve loved them all”), it is often played at weddings and funerals.

9 “Look at him working, darning his socks in the night when there’s nobody there…”

“Eleanor Rigby” (from “Revolver” LP, 1966)

This groundbreaking single features no Beatles playing instruments, with only a string quartet, McCartney’s lead vocal and Lennon and Harrison adding harmonies. The lyrics offer a remarkable commentary on loneliness, describing an old woman sweeping up rice following a wedding and a clergyman dutifully “writing the words to a sermon that no one will hear.”

10 “Baby says she’s mine, you know, she tells me all the time, you know, she said so…”

“I Feel Fine” (single, 1964)

When Lennon heard feedback from a guitar that had been inadvertently left leaning on an amplifier, he wanted the sound included in the intro to the band’s newest single, “I Feel Fine.” It was one of many “happy accidents” that occurred during Beatles recording sessions over the years that brought such unusual sounds to listeners’ ears, even when the accompanying words were just simplistic love songs.

11 “Why she had to go, I don’t know, she wouldn’t say…”

“Yesterday” (from “Help!” LP, 1965)

McCartney fell out of bed one morning, sat at the piano, and this iconic song came out almost fully formed. He was sure he must’ve heard it somewhere before, but it was indeed a brilliant original melody. It was the first group song featuring only a solo Beatle, with Paul playing acoustic guitar and singing lyrics that yearned for easier, happier times (“I said something wrong, now I long for yesterday”).

12 “Nothing you can say, but you can learn how to play the game, it’s easy…”

“All You Need is Love” (from “Magical Mystery Tour” LP, 1967)

When The Beatles were invited to participate in the first live global television link seen by 400 million people, they were asked to write a song with a universal message everyone could understand. Lennon jumped at the assignment and came up with the simple maxim “All you need is love, love is all you need,” set to a happy-go-lucky chant melody that, naturally, went straight to #1 in 1967’s “Summer of Love.”

INTERMEDIATE

13 “Newspaper taxis appear on the shore, waiting to take you away…”

“Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds” (from “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” LP, 1967)

Because this song title’s three key words start with L, S and D, many observer’s concluded Lennon was writing about the hallucinogenic drug in the lyrics. The colorful images (“Cellophane flowers of yellow and green towering over your head”) reinforced that viewpoint. He always insisted, however, that the impetus for the song was a picture his son Julian drew in kindergarten of his friend Lucy.

14 “You don’t need me to show the way, love, why do I always have to say, love…”

“Please Please Me” (from “Please Please Me” LP, 1963)

Lennon recalled playing around with the word “please,” as in “please listen to my pleas,” but then took it step further with “please please me,” which sends a message about asking for more pleasure. It has since been interpreted as wanting sexual pleasure, but in 1963, this wasn’t something you’d find in a pop song. “Please Please Me” became The Beatles’ first #1 hit in the UK, and reached #3 in the US in 1964.

15 “If looks could kill, it would’ve been us instead of him…”

“The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill” (from “The White Album” LP, 1968)

While in India on their meditation retreat, Lennon observed an American college boy and his mother going on a tiger-hunting expedition, which he opposed. He wrote a lyrical tale about it as if it were a children’s story, using a decidedly mocking tone (‘he’s the all-American, bullet-headed Saxon mother’s son”) and changing the stereotypical Buffalo Bill to the tongue-in-cheek Bungalow Bill.

16 “I’m taking the time for a number of things that weren’t important yesterday…”

“Fixing a Hole” (from “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” LP, 1967)

On the surface, this seems to be a song about repairing an actual hole in the roof, but McCartney later said he was venting frustrations about the pressures of fame and people always wanting something from him (“See the people standing there who disagree and never win”). He yearned to be left alone to explore and experiment, a passion that marked many of the tracks on the “Sgt. Pepper” LP.

17 “But ’til she’s here, please don’t come near, just stay away…”

“Don’t Bother Me” (from “With the Beatles” LP, 1963)

In the early years, George Harrison played lead guitar and sang harmonies, occasionally stepping up to sing lead vocals, but he wasn’t yet confident as a songwriter. Still, he came up with “Don’t Bother Me” for the group’s “With the Beatles” LP, a surprisingly strong melody with somewhat moody lyrics about being left alone to wallow in self-pity. It contributed to his reputation as “the quiet Beatle.”

18 “‘Cause I couldn’t stand the pain, and I would be sad if our new love was in vain…”

“If I Fell” (from “A Hard Day’s Night” LP, 1964)

Lennon’s first ballad, written for the “A Hard Day’s Night” soundtrack, is relatively sophisticated for its time, both musically and lyrically. The narrator appears to be thinking about leaving his current love for someone new, but he wants assurances “that you’re gonna love me more than her.” “If I Fell” was also the B-side of the “And I Love Her” single, which peaked at #12 in the US.

19 “Soon we’ll be away from here, step on the gas and wipe that tear away…”

“You Never Give Me Your Money” (from “Abbey Road” LP, 1969)

All four Beatles expressed how frustrated they were in 1969 with how much of their time was consumed with financial meetings and business headaches. McCartney felt the need to write about it in “You Never Give Me Your Money,” the first track of the lengthy suite on Side Two of “Abbey Road.” The lyrics bemoaned the “funny paper” and breakdown in negotiations that hurt their group dynamics at the time.

20 “When you say she’s looking good, she acts as if it’s understood, she’s cool…”

“Girl” (from “Rubber Soul” LP, 1965)

As 1965 was winding down, The Beatles took a major leap forward in their songwriting with the material they wrote for “Rubber Soul.” Among the tunes Lennon penned was the rather complex, philosophical track “Girl,” which cryptically expressed his curious desire for an artistic, intellectual sort of woman to come along — “the kind of girl you want so much, it makes you sorry.”

21 “Then we’d lie beneath the shady tree, I love her and she’s loving me…”

“Good Day Sunshine” (from “Revolver” LP, 1966)

Lennon and McCartney (and Harrison too) were eager to carefully balance the tracks on each album, alternating moods and tempos and styles. On “Revolver,” the switch from Lennon’s hard-edged and lyrically heavy “She Said She Said” to McCartney’s jaunty “Good Day Sunshine” is a good example. On Paul’s simple song, it’s a nice day and he has a nice girlfriend, and that’s about all there is to it.

22 “Boy, you’ve been a naughty girl, you let your knickers down…”

“I Am the Walrus” (from “Magical Mystery Tour” LP, 1967)

When Lennon was told that college professors were teaching courses interpreting the lyrics of Beatles songs, he chuckled and said, “Here’s one they’ll never figure out.” This extraordinary track is a pastiche of literary references, playground nursery rhymes and cryptic, nonsensical phrases set to a lugubrious arrangement inspired by a British police siren. It’s one of Lennon’s most extraordinary works.

23 “Gather ’round, all you clowns, let me hear you say…”

“You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away” (from “Help!” LP, 1965)

Lennon went through a phase when he was especially enamored with Bob Dylan — his songs, his voice, his overall persona. This manifested itself most overtly in “You’ve Got to Hide Your Love Away,” a Lennon number from the “Help!” film soundtrack. He later said he was furtively writing a message to manager Brian Epstein, who was forced to keep his homosexuality a secret.

24 “Sweet Loretta Martin thought she was a woman, but she was another man…”

“Get Back” (single, 1969)

If you watch Peter Jackson’s 2021 eight-hour documentary “The Beatles: Get Back,” you’ll watch in awe as McCartney comes up with the melody and feel for the song “Get Back” seemingly out of thin air while no one is paying much attention. It’s one of McCartney’s most compelling rockers, with lyrics that focus on the band’s desire to “get back to their roots” on their “Let It Be” album.

DIFFICULT

25 “‘We’ll be over soon,’ they said, now they’ve lost themselves instead…”

“Blue Jay Way” (from “Magical Mystery Tour” LP, 1967)

Harrison was staying at a rented home in the Hollywood Hills (on a street called Blue Jay Way), waiting for a friend to arrive, who was two hours late because of foggy conditions. He busied himself by writing this spacey song about it. Every Beatles tune was combed over for hidden meanings (were they lost on the road, or had they lost their way in life?), but Harrison said this song had no lyrical depth.

26 “In my mind, there’s no sorrow, don’t you know that it’s so?…”

“There’s a Place” (from “Please Please Me” LP, 1963)

The Beatles’ songwriters were working under pressure to produce songs to fill their debut album, and this one, mostly by Lennon, sounds hurried and not particularly noteworthy. Lyrically, the “place” he is writing about is not geographical — it’s his mind, the place he likes to go for solace when he feels down and out. Lennon wrote quite a few songs at this point about feeling “blue.”

27 “Everybody pulled their socks up, everybody put their foot down, oh yeah…”

“I’ve Got a Feeling” (from “Let It Be” LP, 1970)

Lennon and McCartney often wrote separately and then helped each other finish their songs. In this case in early 1969, they took two songs that shared a similar structure and chord pattern and mashed them into one. McCartney’s tune has “a feeling deep inside,” no doubt about his bride-to-be Linda, while John’s wearily points out, “everybody had a hard year.” They recorded it live on the Apple rooftop.

28 “You’re giving me the same old line, I’m wondering why…”

“Not a Second Time” (from “With the Beatles” LP, 1963)

Here’s yet another example of Lennon crying and hurt because some girl has disappointed or betrayed him, and he’s telling her she won’t be getting a second chance with him. He sings it convincingly, and it’s a competent piece of work from the “With The Beatles” album, but it’s unremarkable, like two or three throwaway songs found on each of The Beatles’ first five LPs.

29 “But listen to the color of your dreams, it is not living, it is not living…”

“Tomorrow Never Knows” (from “Revolver” LP, 1966)

George Martin called this Lennon song from “Revolver” to be “absolutely groundbreaking.” It’s based around only one chord, with lyrics about expanding one’s consciousness through recreational drug use (“Lay down all thoughts, surrender to the void”). Surrealistic sound effects created through home-made tape loops gave the track a very trippy sound, paving the way to more sonic experiments.

30 “I know it’s true, it’s all because of you, and if I make it through, it’s all because of you…”

“Now and Then” (single, 2023)

Unfinished demos of songs Lennon was working on at the time of his death in 1980 became the finished Beatles songs “Free as a Bird” and “Real Love” when Paul, George and Ringo collaborated in 1995-1996. A third song, “Now and Then,” was finally completed in 2023 thanks to audio restoration technology advancements. Lyrically, it’s an homage to love and how we mean it even if we don’t always show it.

31 “You could find better things to do than to break my heart again…”

“I’ll Be Back” (from “A Hard Day’s Night” LP, 1964)

Lennon sure seemed to love writing songs that center on someone breaking his heart. This time, though, it’s not so threatening because he’s confused about his feelings (“If you break my heart I’ll go, but I’ll be back again”). I’ve always loved this one because of the tight harmonies and melancholic melody, but it has received very little attention as the final track on the “A Hard Day’s Night” LP.

32 “Tell me, tell me, tell me the answer, you may be a lover but you ain’t no dancer…”

“Helter Skelter” (from “The White Album” LP, 1968)

McCartney was inspired by the latest music from The Who to have a go at writing something that would freak everyone out and prove he wasn’t just a ballad writer. In England, a helter skelter was a fast, scary, spiral fairground ride, and he used that image go make the analogy to a frenetic sexual “ride,” exemplified by harsh guitars, thundering bass and shouted vocals.

33 “Had you come some other day, then it might not have been like this…”

“If I Needed Someone” (from “Rubber Soul” LP, 1965)

Carried by shimmering 12-string guitar and glorious three-part harmonies, Harrison’s “If I Needed Someone” was curiously dismissed by its composer at the time as “like a million other songs written around the D chord,” but I’ve always loved it. Lyrically, the narrator is telling a woman he would love to be in a relationship with her if he wasn’t already in love with someone else.

34 “Waiting to keep the appointment she made, meeting a man from the motor trade…”

“She’s Leaving Home” (from “Sgt. Pepper,” 1967)

McCartney was touched by news reports of girls who ran away from home to join the hippie movement in California, and was inspired to write a short story describing her parents’ despair when they found her farewell note. Lennon added less sympathetic lines that implied the parents “gave her everything money could buy” but apparently not sufficient attention nor affection.

35 “Don’t you know I can’t take it, I don’t know who can, I’m not going to make it…”

“I Call Your Name” (from “Long Tall Sally” EP, 1964)

Lennon said this was among the first songs he ever wrote, around 1960, and even then, his lyrics focused on the pain of unrequited love instead of the happy love songs that would be The Beatles’ stock in trade during their initial releases. “I Call Your Name” appeared on the US-only LP “The Beatles’ Second Album,” and on a British EP at the same time (early 1964). The Mamas and Papas recorded a cover version in 1966.

36 “The men from the press said, ‘We wish you success, it’s good to have the both of you back…'”

“The Ballad of John & Yoko” (single, 1969)

Written almost as a diary entry, Lennon detailed his whirlwind marriage and honeymoon travels with Yoko in March 1969. Despite tensions between Lennon and McCartney at the time, the two collaborated without George or Ringo to quickly record the song and release it as a stand-alone single, and it reached #8 in the US, even with its controversial use of “Christ! You know it ain’t easy” in the lyrics.

****************************