Who’s gonna play this old piano after I’m not here?

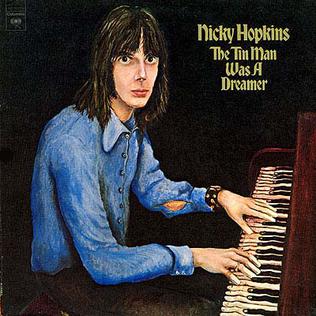

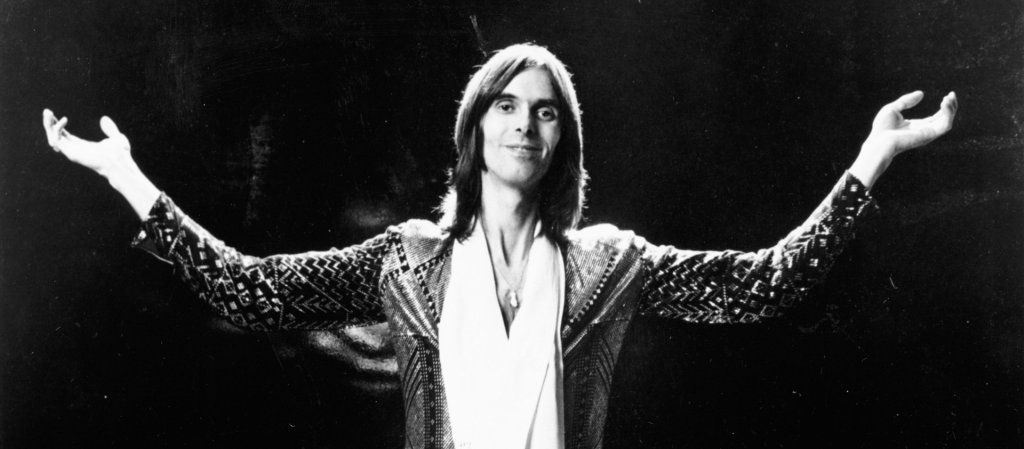

This year’s inductees into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame were announced recently, and I’m pleased to see several vintage rockers finally get the nod: Joe Cocker, Bad Company, Warren Zevon, Nicky Hopkins. I first wrote about Cocker two weeks ago, and I’ll be profiling the others in the coming weeks. Today’s post is on brilliant session keyboard player Nicky Hopkins.

**********************

There’s an important truth about many of the legendary bands whose albums are so important to us: Quite often, the music was made much more interesting and dynamic because of the contributions of incredibly talented session musicians.

To the public at large, even to many music lovers, these superb instrumentalists are mostly anonymous. Their peers in the music business know who they are — these unsung heroes who play keyboards, guitars, saxes and percussion to fill out the arrangements of songs written by the main recording artist — but the majority of the listening audience doesn’t have a clue, and perhaps doesn’t much care.

When you take a close look at the list of classic rock songs and more than 250 albums on which pianist Nicky Hopkins appeared, I’m pretty sure it’ll leave you stunned, especially if you’re a casual fan who’s never heard of Hopkins before reading this piece.

Consider these iconic artists with whom Hopkins made an impact: The Who. The Rolling Stones. The Kinks. The Beatles. John Lennon. Jeff Beck. Steve Miller Band. Ringo Starr. Joe Cocker. Jefferson Airplane. Jerry Garcia Band.

And those are just the A-list names. There’s also Donovan, Quicksilver Messenger Service, Carly Simon, Art Garfunkel, Peter Frampton, Harry Nilsson, Graham Parker, Badfinger, Cat Stevens and Jennifer Warnes, and more.

Because I’m an aficionado (read: music trivia nerd) who absorbs all sorts of information about the albums I’ve bought, I’ve been aware of Hopkins’ name since at least 1969 when it appeared on the credits of The Rolling Stones’ “Let It Bleed” LP, and I’ve made note of his musical contributions ever since. He was a “first call” keyboard man for a couple decades, and his piano solos and the recorded parts he provided were essential to countless classic tracks.

To some extent, Hopkins’ stature in the business benefited from fortunate timing. My friend Irwin Fisch, a skilled keyboard player, arranger and composer and an associate professor at New York University, explains: “In the first wave of rock in the ’50s, the songs were almost entirely blues-based, and guitar-based. The piano players just found a way to take their backgrounds in blues and jazz and fit to a guitar-based framework. But when the British Invasion bands of the ’60s, which were still mostly guitar-forward, starting writing more creatively, there was an opening for skilled piano players to invent a role and wrangle a lot of different influences. Hopkins did that with The Stones and The Who early on. The guitar-centric industry created Nicky Hopkins; if those bands had actual piano players, we probably wouldn’t be talking about him.”

Indeed. Hopkins grew up in the Greater London area and showed remarkable potential on piano before he was five years old. He won a scholarship to the Royal Academy of London as a teen and left school at 16 to play with a number of regional British bands in the early ’60s. But he suffered from Crohn’s disease and was hospitalized for nearly two years in his late teens, undergoing a series of operations that left him in frail health for most of his life.

His precarious health left him too weak for the rigors of touring, which caused him to concentrate on session work and decline invitations to join bands that frequently went on the road. The Who, in particular, were eager to have Hopkins in their lineup after his stellar work on their “My Generation” debut LP and various singles in the mid-’60s.

“Pete Townshend told me if I ever wanted to be in a band, he wanted me to consider them first,” said Hopkins in 1972. “I wasn’t sure I was strong enough and, in the end, nothing happened, but they were probably my favorite act to work with. Their material is so strong, but it was left up to me what I played on their records. Pete Townshend would bring demos in for us to listen to, and they were incredible. Sometimes they sounded as good as the finished project. But the piano bits are basically my own.”

If you want to hear Hopkins at his best, you need look no further than “The Song is Over,” the stellar track from “Who’s Next” that ranks as one of the finest moments in The Who’s entire catalog. Seasoned keyboard man Chuck Leavell, who has recorded and toured extensively with The Rolling Stones and The Allman Brothers, said, “Nicky would come up with these little vignettes that would make you go, ‘Wow, that bit MAKES that song.'”

Said Fisch, “It’s safe to say that every pop and rock piano player owes him, and they’ll all say so. You can hear his licks, his rhythms, and his arranging in many of the piano parts conceived by most of the players who have the biggest footprints in pop and rock — Elton John, Bill Payne, Roy Bittan, Chuck Leavell, among others.”

In addition to his involvement with The Who, Hopkins participated in many sessions with The Kinks during their early heyday in the 1965-1968 period, including the hit “Sunny Afternoon” and albums like “The Kink Controversy,” “Face to Face” and “Something Else.” Kinks guitarist Dave Davies recalled, “Nicky was inspiring, and talented, but he was invisible. It’s an instinct. It’s an art form, being a good session man.”

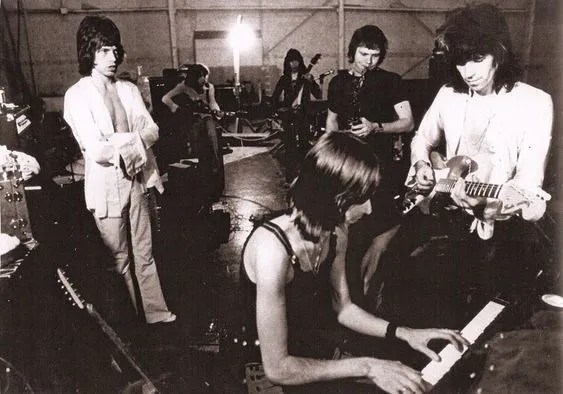

In a more prominent way, Hopkins was featured on dozens of classic Rolling Stones recordings. That’s him doing the classically-themed piano on “She’s a Rainbow” (1967), the relentless keyboard throughout “Sympathy For the Devil” (1968), the dramatic intro to “Monkey Man” (1969), the main melody behind “Angie” (1973), and the fine piano work on “Time Waits For No One” (1974), “Fool to Cry” (1976) and “Waiting on a Friend” (1981).

“He had an intuitive feeling of where the piano should sit in the mix,” said Keith Richards. “He could do the most incredible stuff. You could’ve sworn Otis Spann was in the room, which, for an English kid in the 1960s, was absolutely amazing. I don’t think Nicky knew how good he was — his instinct for the right note at the right place. I’d have a song, half written, we’re working it up in the studio, and he comes in with a riff that changes the song. This little white kid, he was maybe 18, and he sounded like he was in Mississippi, or Chicago. So authentic.”

His dynamic fills and solos with those three bands attracted the attention of John Lennon, who invited him to play electric piano on The Beatles’ single version of “Revolution,” and Hopkins nailed it in one take. “It’s amazing how he lifted that whole track. He’s a fantastic guy.” Lennon brought him back three years later when he was recording the songs for his iconic “Imagine” album. It’s Hopkins’ piano you hear on the gorgeous ballad “Jealous Guy” as well as the rollicking “Crippled Inside” and “Oh Yoko.”

The other three Beatles shared Lennon’s admiration for Hopkins’ talent. In 1973, Ringo Starr brought him in to augment the recordings of his two #1 hits, “Photograph” and “You’re Sixteen”; George Harrison tapped Hopkins for his #1 hit “Give Me Love” the same year; and much later, Paul McCartney used Hopkins on his 1989 LP “Flowers in the Dirt.”

Hopkins enjoyed the session work and was honored to be asked to play with so many different acts, but he pined to be able to play on stage, so he joined the Jeff Beck Group for a spell, recording Beck’s groundbreaking debut LP “Truth” with Rod Stewart and Ron Wood, and going on a short tour, but it proved more than his health could handle. When he relocated to the Bay Area of California, where he spent much of the last half of his life, he recorded with the Jefferson Airplane on their “Volunteers” album and the Steve Miller Band for their “Brave New World” and “Your Saving Grace” LPs.

He also actually became a member of Quicksilver Messenger Service for a year or so, recording and occasionally performing. He made an appearance with the Airplane on stage at Woodstock in 1969 for their set, but he pretty much resigned himself to session work from then on.

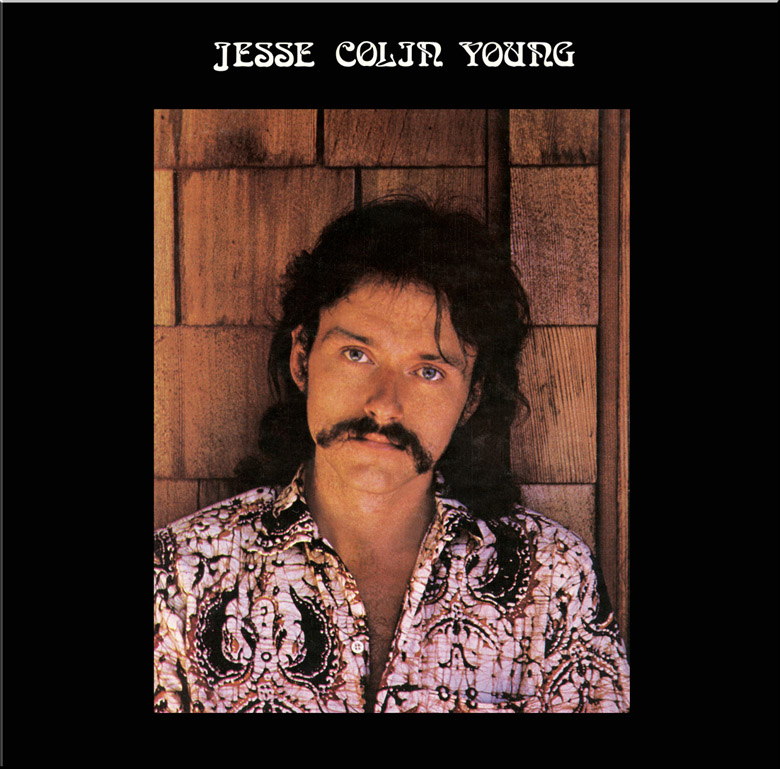

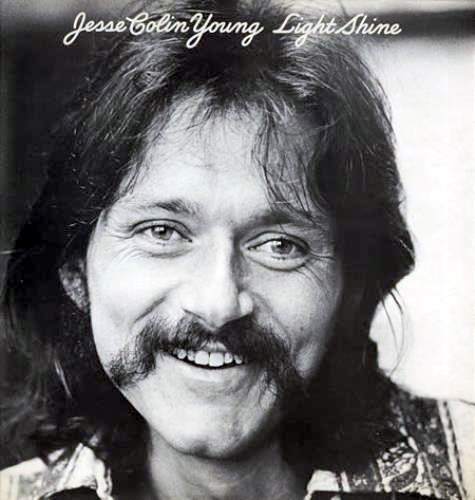

His ambitious first wife Dolly thought he was talented enough to be a star in his own right and pushed him to release two solo LPs — the 1973 disc “The Tin Man Was a Dreamer” includes the astonishing instrumental “Edward” and the equally memorable “Pig’s Boogie” — but Hopkins conceded he wasn’t really cut out for the limelight. His second wife Moira said in the 1990s, “He was a side man, not a front man. He was the wrong person to be living that sort of lifestyle. He wasn’t physically strong enough for it, and it took him to a bad place eventually.”

Partly to help ease the pain of his Crohn’s disease and other ailments, Hopkins grew susceptible to the lure of alcohol and eventually heroin, both in easy reach on the road and in the studios, and they might have killed him back in 1972 if not for jazz pianist Chick Corea. “On the day we met,” Corea recalled, “I asked him, ‘How are you?’ He replied, ‘Not so good. The doctor told me I have two weeks to live unless I quit heroin.’ I told him I was going to get him into rehab, and I probably saved his life at that moment. Nicky didn’t think it would work, but it did.”

After his recovery, Hopkins worked exclusively as a session man, playing on such albums as Carly Simon’s “No Secrets,” Peter Frampton’s “Something’s Happening,” Jennifer Warnes’ debut LP, Jerry Garcia’s “Reflections,” Rod Stewart’s “Foot Loose and Fancy Free,” Art Garfunkel’s “Breakaway,” Joe Cocker’s “I Can Stand a Little Rain,” The Who’s “By Numbers,” Donovan’s “Essence to Essence” and The Stones’ “It’s Only Rock and Roll.”

Benmont Tench, Tom Petty’s keyboard player, said of Hopkins, “I’d always pay close attention whenever I saw his name on the credits. He always brought something beautiful. He had this invaluable ability to realize where to start playing in the song.”

If you watch “The Session Man,” the Nicky Hopkins documentary now streaming on Amazon Prime Video, you’ll hear numerous musicians speaking reverentially about Hopkins’ extraordinary musical abilities.

Regarding the delicate piano part on Cocker’s hit “You Are So Beautiful,” Peter Frampton said, “It gives me goosebumps every time I hear it.”

Mike Hurst, producer on Cat Stevens’ little-known debut LP “Matthew and Son” back in 1967, had this to say about Hopkins: “With most session musicians, they come in, they do their job for three hours, and disappear. Nicky wasn’t like that. He always wanted to do another take if he felt he could make it better…even though his first take was often flawless.”

Chris Welch, writer for England’s Melody Maker music publication, wrote, “If you look at the list of songs he played on, it’s genius, absolutely genius. If you took Nicky out of the mix, the magic disappeared. He played semi-classical parts, gospel parts, blues, boogie-woogie, rock and roll. He could do it all.”

Towards the end of his life, Hopkins worked as a composer and orchestrator of film scores, with considerable success in Japan. Hopkins died in 1994, at the age of 50, in Nashville from complications resulting from intestinal surgery related to his lifelong battle with Crohn’s disease. It wasn’t until 2018 when friends and family members were able to arrange a physical tribute to Hopkins in the form of a “keyboard bench” that sits in a park near his birthplace in Perivale, a London area neighborhood.

Mike Treen, a veteran TV producer who directed “The Session Man,” is a big fan. “For all my years in the business, this is the doc that I’m really proudest of,” he said. “The hard bit for us was finding the distributors, the platforms. They want films about stars, so when I mentioned Nicky Hopkins, they’d go, ‘Well, he’s not a name.’ And I’d say, ‘But that’s the point! He’s got an amazing story to tell that few people have ever heard.’ So that’s why it took us five years.”

I suppose it’s never too late to honor a man’s work, and the tardy induction of Nicky Hopkins into the R&R HOF is certainly an example of that. As you listen to the tracks on the Spotify playlist below, I urge you to pay close attention to the piano. Hopkins was, as soul singer P.P. Arnold put it, “the real deal.”

**************************