I’d listen to the radio: A Lost Classics re-run

I’m going to be traveling internationally over the next few weeks, so I’ll be re-running a few posts of “lost classics” from the first few years of “Hack’s Back Pages” (2015-2018). I’m fairly certain many of my current readers weren’t seeing my blog at that point, so these entries may very well be new to you. In any case, I’m offering some great “diamonds in the rough” from albums in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, and I think you’ll find them well worth your attention.

************************

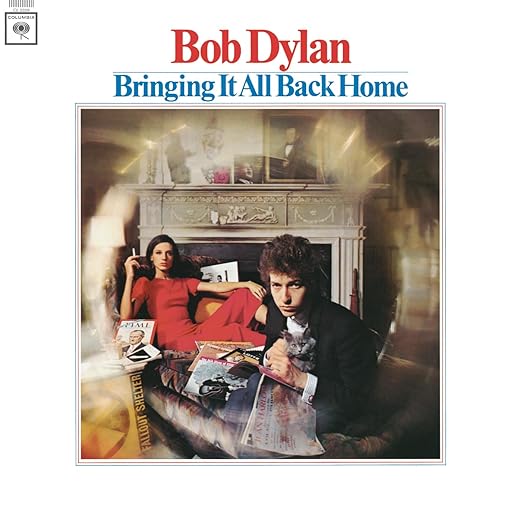

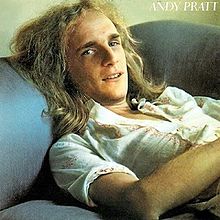

“Avenging Annie,” Andy Pratt, 1973

This guy is a perfect example of an artist who was highly praised by critics and others in the music industry but never embraced by the public. From an upscale Boston family and ’60s Harvard education, Pratt chose to pursue both soft/folk rock and experimental musical genres. His debut album in 1973 included the minor classic “Avenging Annie,” which features great piano and vocals wrapped around a tremendous melody and arrangement, but it somehow never managed better than #78. The Who’s Roger Daltrey recorded a killer rendition on his 1977 solo LP “One of the Boys,” but otherwise, the song faded into the woodwork. Pratt had one more flirtation with the charts with 1976’s “Resolutions” LP and the single “That’s When Miracles Occur,” but they too underperformed commercially. After that, he became a Christian rock devotee and moved to The Netherlands, where he was happy with relative obscurity.

“Blind Love,” Allman Brothers, 1979

Such a cursed band, The Allman Brothers. They struggled mightily in the 1969-1971 period, playing upwards of 300 gigs a year, becoming one of the finest bands America has ever produced, with phenomenal guitar interplay from Duane Allman and Dickey Betts, vocals and organ from younger brother Gregg Allman, and an expert rhythm section. But then Duane died at age 24 just as the world was turning on to the band, followed by bassist Berry Oakley’s death a year later. Nevertheless, the band enjoyed a few years of commercial success (“Ramblin’ Man”) before imploding in ugly quarrels and ego-driven rivalries. Somehow, they found a way to bury hatchets and reconvene in 1979 for a surprisingly strong LP, “Enlightened Rogues,” which features a ferocious blues track called “Blind Love,” featuring Gregg’s angst-ridden vocals and outstanding guitar by Betts and his new compatriot Dan Toler.

“Talk It Over,” Grayson Hugh, 1988

Why this guy didn’t become a bigger commercial success is one of life’s mysteries. Hugh has an incredible voice, perfect for rhythm and blues songs (especially for a white boy!), and his debut LP “Blind to Reason” in 1988 is well worth another look. His original songs “Romantic Heart,” “Tears of Love,” “Finally Found a Friend” and the title track show great promise. But it was “Talk it Over,” co-written by Sandy Linzer (who co-wrote “Let’s Hang On” and “Working My Way Back to You” for The Four Seasons), that put Hugh into the Top 20 in 1989. Hugh was widely praised for his follow-up LP, “Road to Freedom” (1992), and two songs from it appeared in the “Thelma and Louise” soundtrack. But things didn’t work out and he struggled with alcoholism; he’s on the mend and still creating new music today.

“Sea of Joy,” Blind Faith, 1969

Eric Clapton and Steve Winwood had admired each other since they first crossed paths in 1966 when Clapton was with John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers for a brief period before forming the legendary Cream, and Winwood was all of 18, singing for Spencer Davis Group before forming Traffic. They vowed to work together some day. In 1969, Cream had imploded, and Traffic was on hiatus, and the two musical giants decided to give it a go to see what might happen. The result was Blind Faith, born of good intentions but conflated by record promoters beyond what anyone involved wanted. They lasted all of five months…but fortunately for us, they produced a spectacular record that still resonates today. Winwood’s delicate acoustic “Can’t Find My Way Home” and Clapton’s “Presence of the Lord” show up on classic rock radio periodically, but another track you need to know is “Sea of Joy,” which features Winwood singing at his best, Ric Grech’s electric violin, and Clapton’s understated but sturdy guitar playing.

“Dinah-Flo,” Boz Scaggs, 1972

William “Boz” Scaggs was a Texas product who moved to The Bay Area in the mid-’60s, where he helped found The Steve Miller Band, playing guitar and writing songs for their first two LPs. His solo career began with a memorable debut LP that includes the FM radio classic “Loan Me a Dime,” with Duane Allman on lead guitar. Scaggs had always had a fondness for R&B, and his albums from the early ’70s onward had a prominent “blue-eyed soul” bent. His outstanding 1976 LP “Silk Degrees” — which includes the #3 hit “Lowdown” as well as “Lido Shuffle,” “It’s Over,” “What Can I Say,” “Georgia” and the Scaggs song Rita Coolidge made famous, “We’re All Alone” — still stands as one of the greatest R&B albums by a white artist. Back in 1972, though, when he was still warming up, he came up with a jewel of a tune called “Dinah-Flo,” and the recording from his “My Time” album is simply irresistible.

“I.G.Y.,” Donald Fagen, 1982

I was among those who mourned when I heard that Donald Fagen and Walter Becker had decided to end their Steely Dan collaboration in 1980 following the release of the brilliant but troubled “Gaucho” LP. Becker had personal problems, and frankly, Steely Dan hadn’t been a band at all since maybe 1974. For “Pretzel Logic,” “Katy Lied,” “The Royal Scam,” “Aja” and “Gaucho,” Fagen and Becker had assembled legions of session musicians to insert their solos and individual parts on a song-by-song basis. So it wasn’t too surprising that, when Fagen went on his own in 1982 with “The Night Fly,” he continued the same formula to such an extent that it sounded pretty much like a new Steely Dan LP. Fagen chose to compose a song cycle about growing up in the 1950s in suburban New Jersey, where he heard about such things as the International Geophysical Year (I.G.Y.), a worldwide renewal of scientific exchange and cooperation following the death of Russian leader Josef Stalin. It was a time of hope and discovery, and Fagen recalled it all in “I.G.Y.,” which prays for the best: “We’ll be clean when their work is done, we’ll be totally free, yes, and totally young, what a beautiful world this could be, what a glorious time to be free…”

“Can’t Let a Woman,” Ambrosia, 1976

Singer-songwriter David Pack gets most of the laurels for the work of Ambrosia, the band he founded in 1971 in L.A. Originally the group preferred the progressive rock genre, and its first two albums showed this prominently, including the first two singles, “Holding On to Yesterday” (#17 in 1975) and “Nice, Nice, Very Nice” (1976). But their enduring reputation was as a soft-rock band because of their next three singles: the #3 hit “How Much I Feel” (1978) and the back-to-back hits “Biggest Part of Me” (#3) and “You’re the Only Woman” (#13), both in 1980. Savvy fans who know the group’s first two LPs will no doubt agree with me that deep tracks like “Time Waits For No One” and especially “Can’t Let a Woman” show off Ambrosia’s technically gorgeous sound from their earlier days.

“Last Plane Out,” Toy Matinee, 1990

This startling track came out of nowhere in early 1990 to get significant airplay on the FM mainstream rock stations but, sadly, went nowhere on the Billboard Top 40. Its lyrics are somewhat apocalyptic, describing how awful life might be after the end game, and “hoping for passage on the last plane out” before things became unlivable. The music, however, is upbeat and engaging, beautifully produced with great vocal harmonies. The duo of Patrick Leonard and Kevin Gilbert wrote and played the songs for the group they called Toy Matinee, who released just the one album before fading. Gilbert went on to be a prominent producer and a key behind-the-scenes player in Sheryl Crow’s career in the ’90s and beyond.

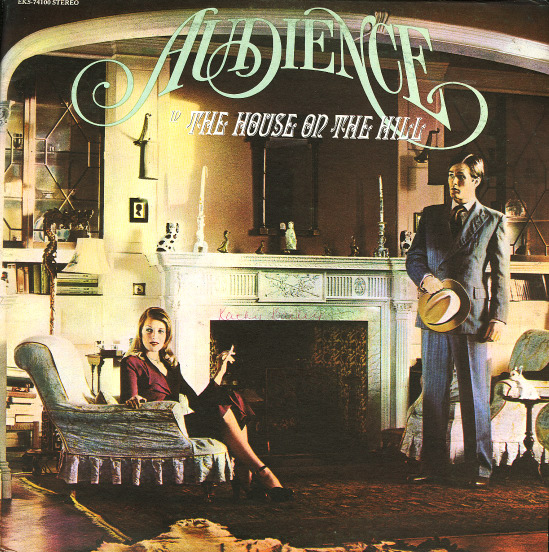

“Indian Summer,” Audience, 1972

The 1969-1975 period was quite fertile for singer-songwriters, especially those who chose introspective ballads (Joni Mitchell, James Taylor, Cat Stevens), but also many groups who offered unusual instrumental arrangements, quirky songs and “acquired taste” vocals. One of these was Audience, a British outfit led by the creativity of Howard Werth and Keith Gemmell. They struggled along at first, releasing two LPs in England to little reaction, before hooking up with Elton John’s first producer, Gus Dudgeon, who helped them hone their third album, “House on the Hill,” into a stronger package that gained US radio airplay. The single, “Indian Summer,” stalled at #74, but the FM stations played this album often, and it’s full of great material I recommend, starting with “Indian Summer.”

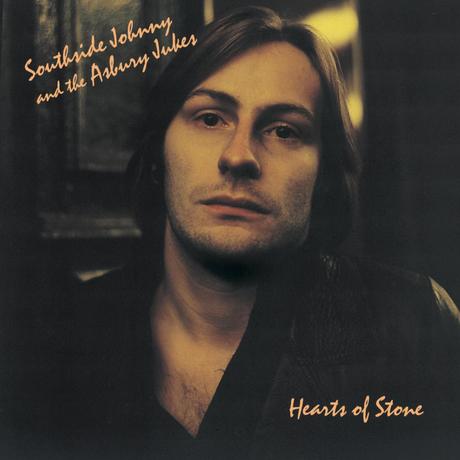

“Talk to Me,” Southside Johnny & Asbury Jukes, 1978

Sadly, this explosive bar band from the Jersey Shore was never able to emerge from the shadows created by the great Bruce Springsteen and his E Street Band, but it wasn’t for lack of trying. Indeed, Springsteen and his guitarist/arranger cohort Miami Steve Van Zandt did everything they could to support “Southside” Johnny Lyon and his sweaty, energetic band, offering original material and producing their first three LPs, but inexplicably, the public failed to embrace them. What a shame — if you ever saw them in concert, you’d never forget it. Any of their first three LPs is worth your time and attention; the third, the 1978 album “Hearts of Stone,” was written entirely by Van Zandt and/or Springsteen, including the Boss’s exuberant “Talk to Me,” propelled by vibrant horns and a frenetic rhythm section. Springsteen didn’t release his own version until 2010, on the extra disc included with the anniversary package of “Darkness on the Edge of Town” (another 1978 release).

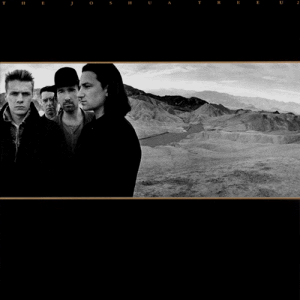

“Bullet the Blue Sky,” U2, 1987

After building a huge base in Ireland, England and elsewhere during the early ’80s, U2 started getting noticed in mainstream America with the single “Pride (In the Name of Love)” and their “Live Aid” appearance, both in 1985. But it was the monumental “The Joshua Tree” LP in 1987 that made them worldwide superstars, a designation they still hold today, because they continue to write and release major, substantial works time after time. “I Still Haven’t Found What I’m Looking For,” “With or Without You,” “Where the Streets Have No Name” — they all help define the U2 sound, led by Bono’s plaintive vocals and The Edge’s like-none-other guitar stylings. Sometimes overlooked on this huge LP is the biting political diatribe “Bullet the Blue Sky,” which was the most incredible moment in their 2007 tour, which I saw twice in eight days. It’s not commercial, by any means, but it’s more than memorable: “Outside, it’s America… outside, it’s America…”

“Poem For the People,” Chicago, 1970

When Chicago (originally Chicago Transit Authority) was a bold new band, its albums broke frontiers, full of amazing amalgams of big band and rock, and hopeful utopian lyrics typical of the 1969-1970 period. Their career grew on the strength of “Make Me Smile,” “Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is?” and “Beginnings,” but there was so much more on those early LPs. “Make Me Smile,” in fact, was part of a 13-minute suite called “Ballet For a Girl in Buchannon,” which included the prom favorite, “Colour My World.” Do yourself a favor and listen to the first four songs on “Chicago” (now known as “Chicago II”) and you’ll find thoroughly engaging music like “Movin’ On” and “In the Country,” and the majestic “Poem For the People,” which is one of Robert Lamm’s finest songs and arrangements.

*************************