What the mama saw, it was against the law

Paul Simon sang the above line in the 1972 hit “Me and Julio Down By the School Yard,” but he chuckled and left it up to us to ruminate on what the mama actually saw. Something naughty, evidently…

Many of us would agree that mothers do seem to have eyes in the backs of their heads, catching us doing stuff we shouldn’t. I remember a children’s TV host in Cleveland in the ’60s who used to sign off with, “You can fool some of the people all of the time, and all of the people some of the time, but you can’t fool Mom!”

It was just over a century ago when President Woodrow Wilson declared the second Sunday of May to be Mother’s Day, a national holiday set aside to honor mothers, motherhood, maternal bonds and the influence of mothers in society. Mom, after all, is “the person who has done more for you than anyone in the world,” said Anna Jarvis, the Suffragette-era activist who spearheaded the move for an official Mother’s Day.

Popular music has not missed out on the opportunity to celebrate mothers — or, at least, to include “mother or mama” in the song title. In genres from hard rock to country, from Top 40 pop to soul, mothers have served as great subject matter for songs of all kinds.

Even that iconoclast, the late Frank Zappa, and his first band, The Mothers of Invention, offered a song called “Motherly Love” on their 1966 debut: “Motherly love is just the thing for you, you know your Mothers gonna love you ’til you don’t know what to do…” So what if it was about the band, not the woman?

Rock music being rebellious, some songs I found don’t really celebrate mothers as much as find fault with them. Queen has a track entitled “Tie Your Mother Down” that, while not espousing bondage, is about a teen couple wanting to keep Mom constrained long enough for them to fool around uninterrupted. On “Synchronicity,” The Police included a blunt track called “Mother” that goes, “The telephone is ringing, /Is that my mother on the phone? /The telephone is screaming, /Won’t she leave me alone?…” There’s a place for such songs, I suppose, but not here, not now.

There are plenty of more recent tunes about mothers, like the poignant “Mother” by Kacey Musgraves (2018) or the racy “Stacy’s Mom” by Fountains of Wayne (2003). But this blog has traditionally explored songs from the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, and that’s where my focus will be on this post. I have selected 15 tunes about mothers that adopt a generally appreciative attitude toward her, some with humor, some with honor and love. I think the Spotify playlist found at the end (and a second playlist of “honorable mentions”) will be well received when you invite your moms, your mothers-in-law, your mothers-to-be or your grandmas over for dinner on Sunday.

Happy Mother’s Day!

**************************

“Your Mother Should Know,” The Beatles, 1967

This track was one of the half-dozen Paul McCartney sing-song numbers recorded by The Beatles in their final three years that John Lennon derisively referred to as “Granny music” (songs that your grandparents would like). Paul said he wrote it on a harmonium in his London home when Liverpool relatives were visiting, inspired by the kinds of songs they used to sing in the parlor at Christmastime. It looked good in a scene in the band’s experimental film “Magical Mystery Tour” with the foursome descending a grand staircase in white tuxedos. Musically, it’s rather slight, but it has a nice sentiment that Dear Old Mom should love: “Let’s all get up and dance to a song that was hit before your mother was born, /Though she was born a long long time ago, Your mother should know…”

“That’s All Right Mama,” Elvis Presley, 1954

In one of his earliest recording sessions, Elvis and his combo were messing around with a speeded-up version of this old Arthur Crudup blues tune. Producer Sam Phillips was immediately struck by it and concluded it was the “blues meets country” sound he’d been looking for, and it ended up as Presley’s first single and, many claim, one of the first rock and roll songs ever. With only minimal distribution or promotion, it didn’t chart nationally but reached #4 on local Memphis charts. Fifty years later in 2004, its re-release reached #4 in the UK. In Crudup’s lyrics, the narrator sings: “Mama she done told me, /Papa done told me too, /’Son, that gal you’re foolin’ with, /She ain’t no good for you,’ /But that’s all right, that’s all right, /That’s all right now, mama, anyway you do…”

“Your Mama Don’t Dance,” Loggins and Messina, 1972

Jim Messina recalled his home environment this way: “My stepfather was into country. He was an Ernest Tubbs/Hank Snow kind of guy. But my Mom loved Elvis, and Ricky Nelson, and R&B stuff. She was shy, though, and didn’t really dance much. So the song’s title, first line and chorus were based on that experience I had growing up in that household.” He fleshed it out with references to curfews and drive-in movies, and “Your Mama Don’t Dance” ended up reaching #4 on US pop charts in late 1972 as Loggins and Messina’s biggest chart hit: “The old folks say that you gotta end your date by ten, If you’re out on a date and you bring it home late, it’s a sin, /There just ain’t no excuse and you know you’re gonna lose, /You never win, I’ll say it again, /And it’s all because your mama don’t dance and your daddy don’t rock and roll…”

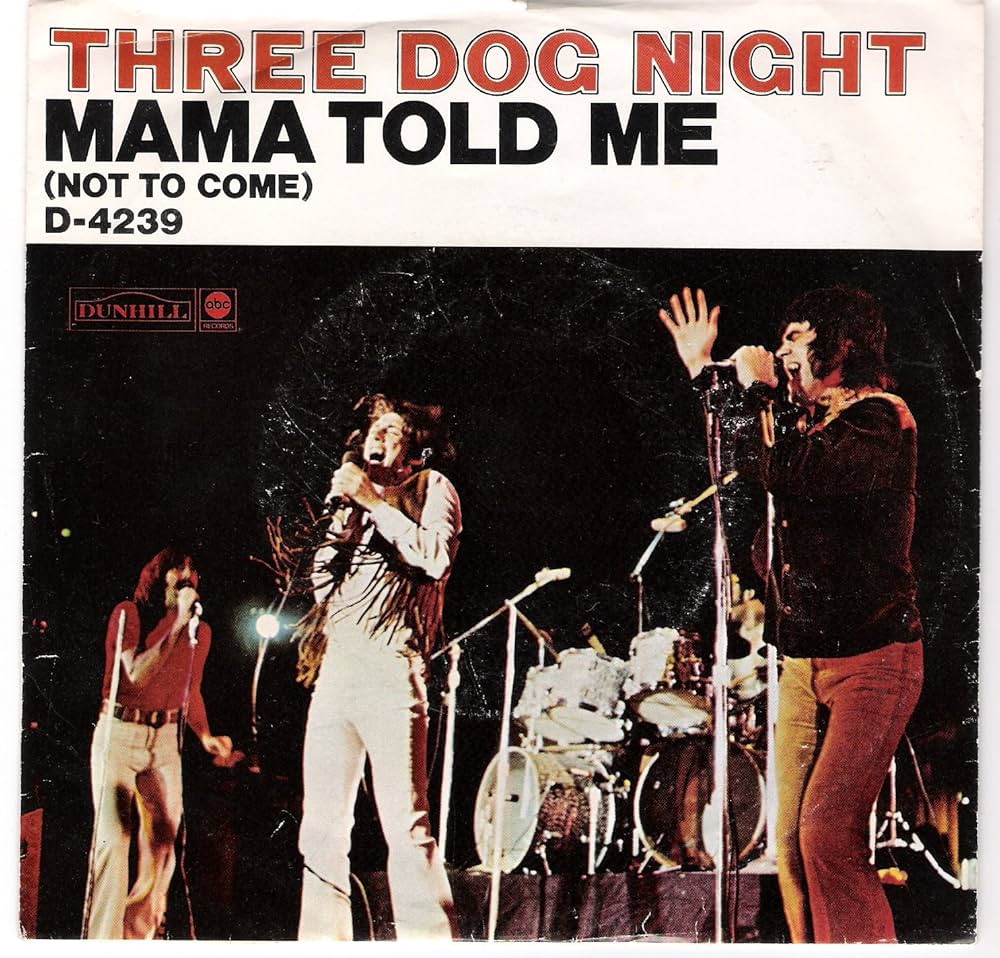

“Mama Told Me Not to Come,” Three Dog Night, 1970

Randy Newman, one of the more celebrated songwriters and film composers of his generation, came up with this tune as part of his 1970 debut release, “12 Songs.” He didn’t achieve much commercial success as a recording artist, but his songs often did well in the hands of others. Three Dog Night had one of the biggest radio hits of 1970 with their version of Newman’s “Mama Told Me (Not to Come),” which features one of his typically sardonic lyrics about a guy who is uncomfortable attending drug parties and realizes he should’ve listened to his mother’s advice: “I seen so many things I ain’t never seen before, /Don’t know what it is, I don’t wanna see no more, /Mama told me not to come, /Mama told me not to come, /She said, ‘That ain’t the way to have fun, son’…”

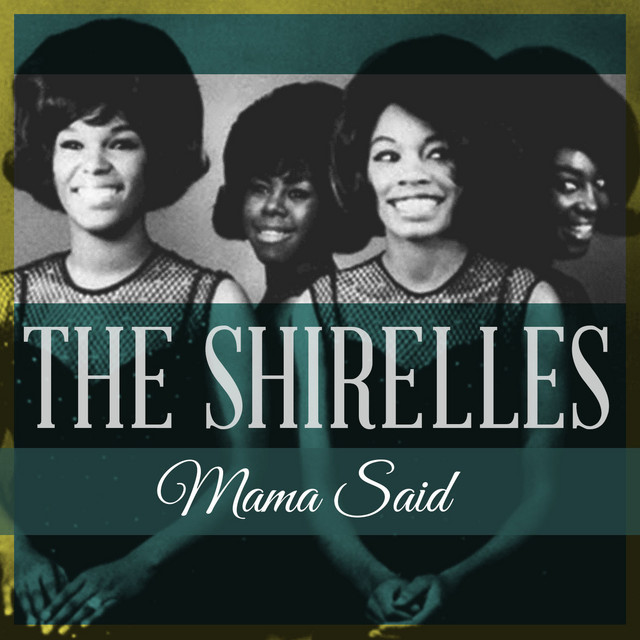

“Mama Said,” The Shirelles, 1961

The Shirelles, a New Jersey-based trio who became one of the early “girl group” successes, had several classic singles during the 1960-1963 period: “Will You Still Love Me Tomorrow,” “Dedicated to the One I Love,” “Soldier Boy,” “Baby It’s You,” “Foolish Little Girl.” One of their best was “Mama Said,” written by Willie Denson and Luther Dixon, which peaked at #4 as their third consecutive Top Five hit. Its lyrics reinforced the wisdom of a mother’s warning about how young love can knock you off your feet: “I went walking the other day, /Everything was going fine, /I met a little boy named Billy Joe, /And then I almost lost my mind, /Mama said there’ll be days like this, there’ll be days like this, my mama said…” The song inspired John Lennon’s “Nobody Told Me” (1980) and Van Morrison’s “Days Like This” (1995).

“Momma,” Bob Seger, 1975

The pride of Detroit’s heartland rock scene, Seger wrote honest, unvarnished rock songs about working-class life in the Midwest. Before breaking out nationwide with the 1976 LP “Night Moves,” Seger plugged away for nearly a decade with various bands and as a solo act until finding the right chemistry with The Silver Bullet Band. Their “Beautiful Loser” album in 1975 gave the first hint of Seger’s composing abilities, and one track, “Momma,” revealed that he didn’t necessarily get along that well with his strict mother. Still, he conceded that although she could be tough, she was always truthful with him: “Oh, how she could control me, /And when I was bad, she’d scold me, /Sometimes she wouldn’t hold me, and I’d cry, /But momma, she never told me a lie…”

“Mother and Child Reunion,” Paul Simon, 1972

In 1971, eager to begin his solo career, Simon was in a Chinese restaurant in New York City one night when he was amused to see a chicken-and-egg dish on the menu creatively called Mother and Child Reunion. “What a great song title,” he thought, and began writing a song that addressed the sometimes fickle nature of the mother-child relationship. Enamored by the strains of Jamaican reggae, he incorporated the intriguing rhythms into the song’s structure, and by early 1972, he had his first solo Top Ten hit. The lyrics describe the “strange and mournful day” when the mother (the chicken) and the child (the egg) are reunited on a dinner plate: “Though it seems strange to say, /I never been laid so low, /In such a mysterious way, /And the course of a lifetime runs over and over again…”

“Mama’s Pearl,” Jackson 5, 1971

The Jackson 5’s fifth single was originally entitled “Guess Who’s Makin’ Whoopee (With Your Girlfriend),” but the folks at Motown intervened, thinking it would be inappropriate for such overt thoughts to be coming out of 12-year-old Michael’s mouth. Producer Deke Richards rewrote a few lyrics and changed the title to “Mama’s Pearl,” and it ended up reaching #2 in early 1971. The track still retaining the lyrical idea that the boy wished his sheltered girlfriend would loosen up and move beyond the making-out stage: “We kiss for thrills, then you draw the line, /Oh baby, /’Cause your mama told you that love ain’t right, /But don’t you know good loving is the spice of life, /Mama’s pearl, let down those curls, /Won’t you give my love a whirl, /Find what you been missing, ooh ooh now, baby…”

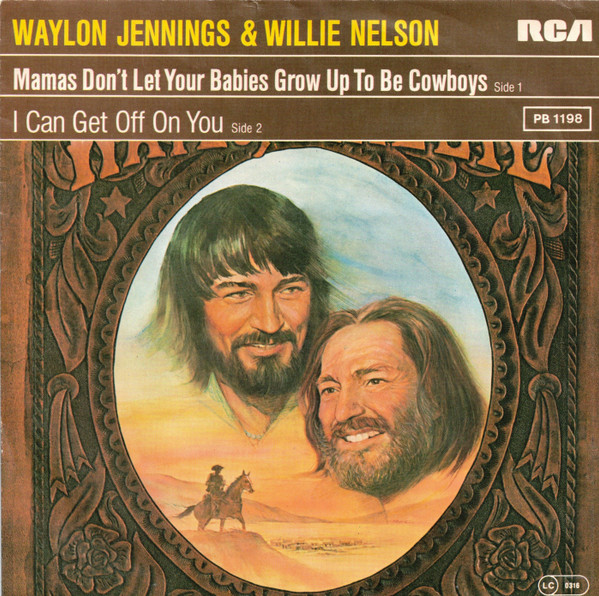

“Mamas, Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys,” Willie Nelson & Waylon Jennings, 1978

In 1978, Nelson and Jennings, both seasoned veterans of country music, were each riding high with a string of #1 albums in 1975-1977. They were good friends and had performed together on occasion, so they chose to collaborate on “Waylon & Willie,” which not only sat at #1 on country album charts for three months, it reached #12 on pop charts as well. A big reason for that was the success of the single, “Mamas, Don’t Let Your Babies Grow Up to Be Cowboys,” with lyrics that urged mothers everywhere to raise their children to be “doctors and lawyers and such” instead of cowboys, because “they’ll never stay home and they’re always alone, even with someone they love…” The track appeared in a scene from the 1979 Jane Fonda-Robert Redford film “The Electric Horseman.”

“Mama Kin,” Aerosmith, 1973

Emerging from the smoky rock clubs of Boston in 1973, Aerosmith launched their career with their self-titled debut album, which flopped, stalling at #166 on US album charts. Some critics dismissed them as “a K Mart version of The Rolling Stones.” By 1976, after the triumph of their next three LPs, the debut album re-entered the charts and peaked at #21, thanks to the tardy success of “Dream On.” The first single, “Mama Kin,” never even charted but became a popular live song at Aerosmith concerts over the years. Its composer, vocalist Steven Tyler, says the lyrics are essentially about “the importance of staying in touch with your family, your roots, your ‘Mama Kin.’ Keeping in touch with mama kin means keeping in touch with the old spirits that got you there in the first place.”

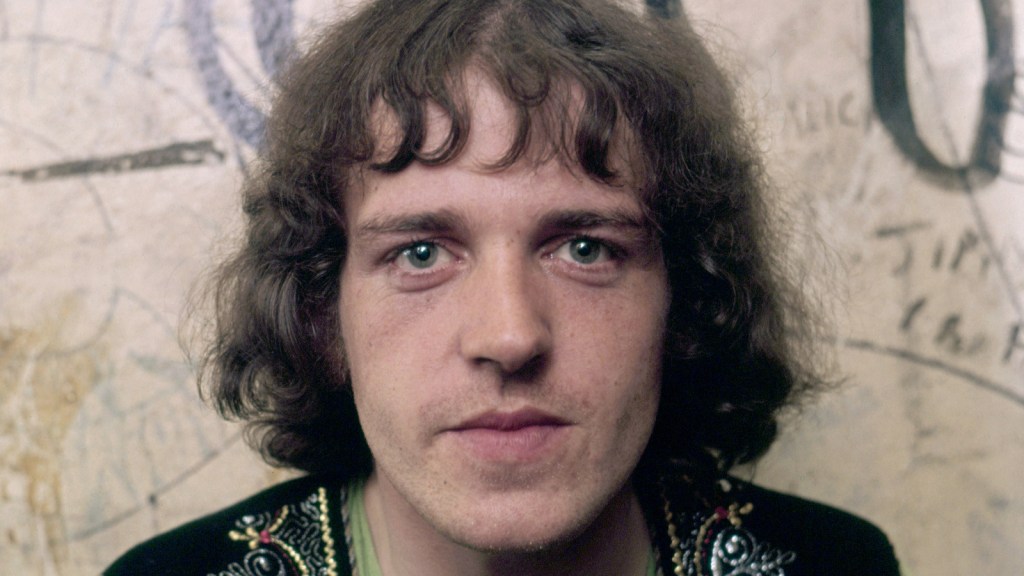

“Never Tell Your Mother She’s Out of Tune,” Jack Bruce, 1969

One of the sadly neglected LPs of 1969 was “Songs For a Tailor,” the solo debut of bassist/vocalist Jack Bruce, following the breakup of Cream eight months earlier. It includes originals like “The Clearout,” which Cream had recorded but didn’t release, and “Theme From an Imaginary Western,” made famous by Mountain at Woodstock. I love the rollicking opening track, “Never Tell Your Mother She’s Out of Tune,” with a title inspired by guitarist Chris Spedding, whose mother was a professional singer. At one of her shows, Spedding pointed out that one of the violin players was out of tune, which angered her — not the fact that the violin needed tuning but that her son had said so publicly. Bruce thought it made a great song title, although the lyrics by Pete Brown go in another direction and make no mention of the incident.

“For a Thousand Mothers,” Jethro Tull, 1969

Tull’s highly praised and popular second album, 1969’s “Stand Up,” offers an eclectic smorgasbord of rock, blues, folk and jazz influences, with Ian Anderson providing the lyrics from fictional scenarios, occasionally mixed with biographical anecdotes or experiences from his personal life. Songs like “Back to the Family” and “For a Thousand Mothers” described Anderson’s relationship with his parents at the time, alternately loving and tempestuous. The latter tune took his mother and father to task for their lack of emotional support of his musical dreams: “Did you hear mother? Saying I’m wrong, but I know I’m right, /Did you hear father? Calling my name into the night, saying I’ll never be what I am now, /Telling me I’ll never find what I’ve already found, /It was they who were wrong, and for them here’s a song…”

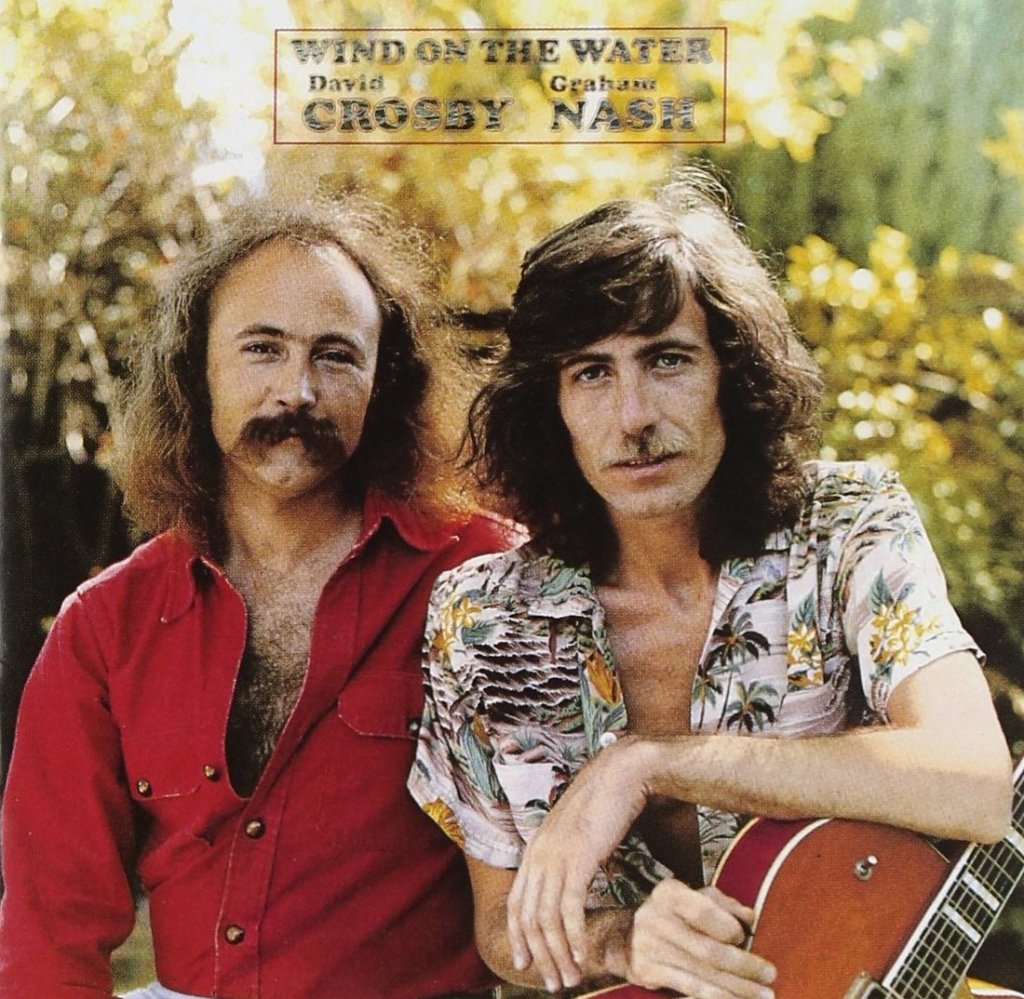

“Mama Lion,” Crosby and Nash, 1975

In 1969-70, Graham Nash had had an intense relationship with Joni Mitchell, and they both later wrote songs about it (Joni’s “Willy” and “My Old Man,” Graham’s “Our House” and “Simple Man”). In 1972, Joni wrote “See You Sometime,” which includes the line, “I run in the woods, /I spring from the boulders like a mama lion.” As he was writing songs for “Wind on the Water,” Nash’s 1975 LP with periodic collaborator David Crosby, he came up with “Mama Lion,” which takes a sobering look at the romantic relationship’s aftermath, based on Mitchell’s earlier tune: “Mama lion, mama lion, I’m starting to sink, /Beneath the sunshine and the icicles, and the things that you think, /There’s a hole in my destiny, and I’m out on the brink, /Mama lion, mama lion…”

“Mother’s Little Helper,” The Rolling Stones, 1966

As the recreational use of mind-altering drugs like marijuana and LSD began increasing in the mid-’60s, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards couldn’t help but notice the hypocrisy of parents who criticized the practice while secretly taking amphetamines and tranquilizers to boost their energy or calm them down. They co-wrote “Mother’s Little Helper,” a phrase some moms used as code to describe their own hushed-up vice: “And though she’s not really ill, there’s a little yellow pill, she goes running for the shelter of a mother’s little helper, and it helps her on her way, gets her through her busy day…” The song peaked at #8 in 1966 as The Rolling Stones’ 12th single. Richards and Brian Jones played altered 12-string guitars to mimic the sound of a sitar, one of several Indian instruments then in vogue.

“Tell Mama,” Etta James, 1968

Written and recorded by Clarence Carter as “Tell Daddy” in 1967, this tune was retitled “Tell Mama” for Etta James to sing when Muscle Shoals Studios producer Rick Hall took charge of the recording session. James objected at first, reluctant to be cast as an Earth Mother, “the gal you come to for comfort,” but it turned out to be her biggest hit on the US pop charts, reaching #23 (and #10 on R&B charts). Over a spirited, horn-driven arrangement, James sings about a young man who’s betrayed by his girl, after which his mother reaches out to give him some TLC: “She would embarrass you anywhere, /She’d let everybody know she didn’t care… /Tell Mama all about it, /Tell Mama what you need, /Tell Mama what you want, /And I’ll make everything all right…”

*************************

Here are a few more that make my “honorable mention” list:

“Mama Gets High,” Blood Sweat & Tears, 1971; “Mother,” Pink Floyd, 1979; “Crazy Mama,” J.J. Cale, 1972; “That Was Your Mother,” Paul Simon, 1986; “Sweet Mama,” The Allman Brothers, 1975; “Mother,” John Lennon, 1970; “Motorcycle Mama,” Neil Young and Nicolette Larson, 1978; “Mother Goose,” Jethro Tull, 1971; “New Mama,” Stephen Stills, 1975; “Mother Nature’s Son,” The Beatles, 1968; “Mama,” Genesis, 1983; “Look What They’ve Done to My Song, Ma,” The New Seekers, 1970; “Mother,” Chicago, 1971; “Mothers Talk,” Tears For Fears, 1985; “Tough Mama,” Bob Dylan, 1974; “Mamma Mia,” ABBA, 1975.

***************************