And I’ll be happy, it’s Christmas once again

I recognize that the holiday season is not full of joy and glad tidings for everyone. Some folks have lost loved ones and must cope with the empty chair at Christmas dinner. Others are reeling from illnesses or other health concerns, and it can be tough to feel much Christmas spirit when we’re ailing.

Still, the Yuletide has the uncanny ability to bring feelings of serenity, love and gratitude, be it in small or large helpings. One way it’s done so for me through the years is with seasonal music. Granted, it can get excessive if you hear the same songs over and over when you’re out in stores and other public places. But I have several dozen Christmas-oriented CD mixes I’ve received as gifts from other music lovers, and they’ve been in rotation at my house and in my car for several weeks now. Hymns, rock songs, folk melodies, even whimsical comedy tunes (some new, some old) segue from one to the next, keeping things interesting instead of predictable.

This year, I’m sharing a dozen or so of my favorite secular Christmas tunes, with some background information you might not have known. I hope this playlist hits the spot, cheering you up and offering warmth and comfort as you gather with family and friends this coming week.

A very Merry Christmas to my readers!

********************

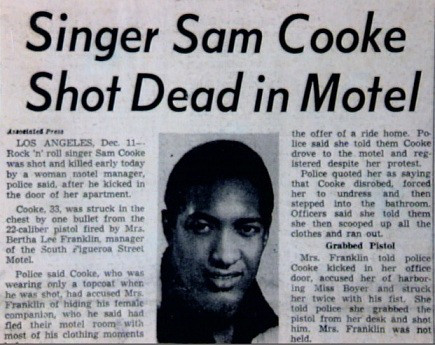

“I Believe in Father Christmas,” Emerson, Lake and Palmer, 1977

Emerson, Lake and Palmer were one of the most bombastic of the British progressive rock bands of the ’70s, with Keith Emerson’s virtuoso keyboards dominating their albums. Each LP featured at least one commercial ballad by bassist/vocalist Greg Lake (“Lucky Man,” “From the Beginning,” “Still, You Turn Me On”). In 1974, as a solo track, Lake collaborated with lyricist Peter Sinfield to write this piece, intended as a protest against the commercialization of Christmas. Musically, it has a grandly traditional, hymn-like flair to it, thanks to Emerson’s suggestion to use a riff from Prokofiev’s “Lieutenant Kijé’s Suite” (1934). Lyrically, though, it’s a bit dark. As Sinfield has said, “It’s about the loss of innocence and childhood belief. It’s a picture postcard Christmas song, but with morbid edges.” Lake’s solo recording reached #2 in the UK, but didn’t chart here. In 1977, ELP re-recorded it for their “Works Part II” album, and that’s the version you’re hearing here.

“Santa Claus is Comin’ to Town,” Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band, 1975

J. Fred Coots and Haven Gillespie teamed up back in 1933 to write this holiday favorite, which became an instant hit when performed on Eddie Cantor’s radio show the following December. Hundreds of recorded versions followed, from Bing Crosby and The Andrews Sisters to The Temptations and Neil Diamond. A version by The Four Seasons reached #23 on the charts in 1962, and Phil Spector included a rousing version by The Crystals on his Christmas collection in 1963. When Springsteen and his band recorded a performance of their rendition in 1975 at a small Long Island college, they used a modified arrangement of The Crystals’ version. It was released as part of the “In Harmony 2” package on Sesame Street Records in 1982, and again as the B-side of the “My Home Town” single in 1985. It had long been familiar to Boss fans through distribution to rock radio stations in the late ’70s, and the band has been featuring it for decades in its playlist any time they’re touring in late November and December.

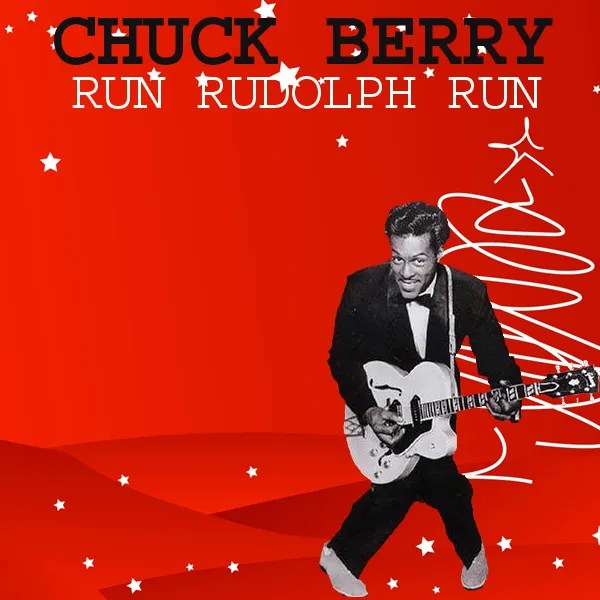

“Run Rudolph Run,” Chuck Berry, 1958

In a November 1958 recording session, Berry and his backing band recorded two tracks: his new tune “Little Queenie” (which would be released as a B-side several months later with “Almost Grown”), and “Run Rudolph Run,” which was basically the same song with different lyrics, made up quickly in the studio by Marvin Brodie and Berry. The label rush-released “Run Rudolph Run” for the Christmas market, and it reached #28 on the charts that year. Both songs are melodically similar to Berry’s earlier signature song “Johnny B. Goode.” Since then, the song has been recorded by such big names as Lynyrd Skynyrd, Sheryl Crow, Cheap Trick, Grateful Dead, Foo Fighters, Jimmy Buffett, Brian Setzer Orchestra, Hanson and Foghat.

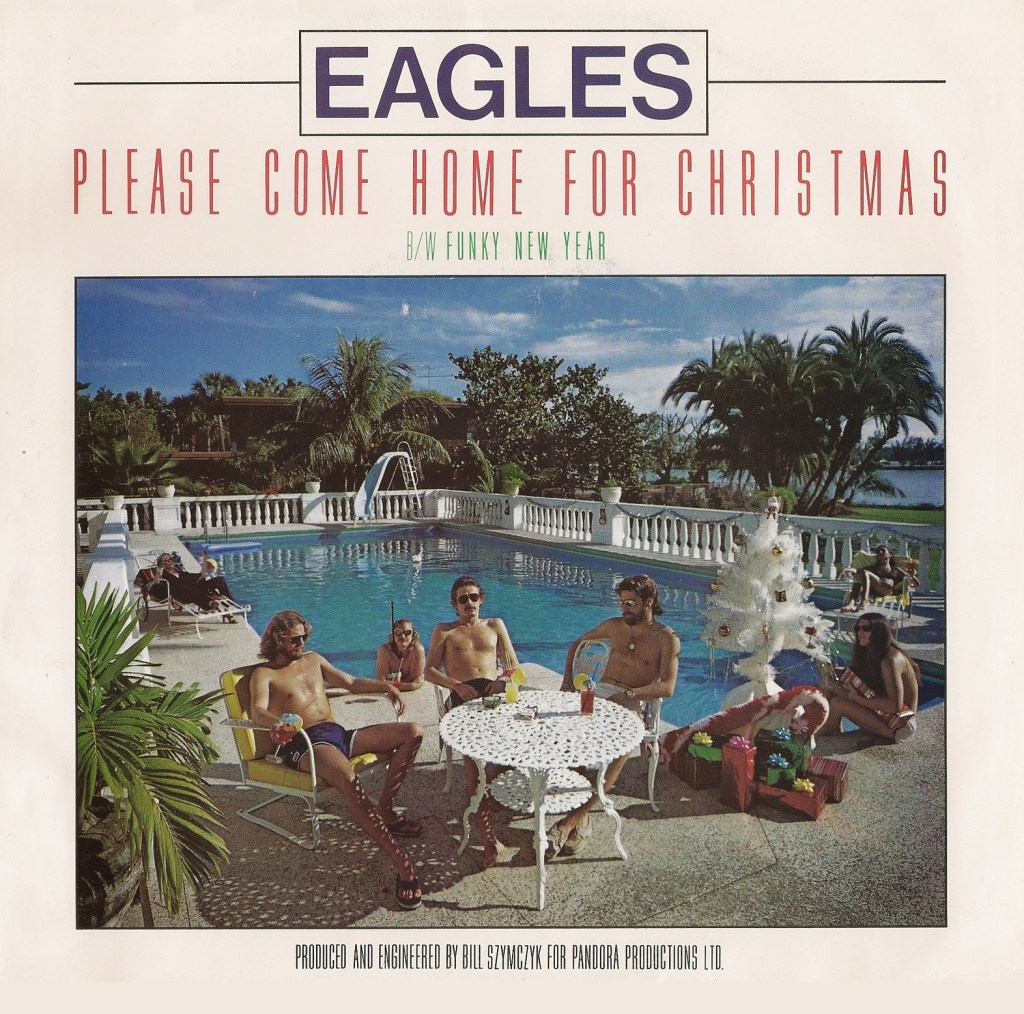

“Please Come Home for Christmas,” The Eagles, 1978

Blues pianist/singer Charles Brown co-wrote this track in 1960 with Gene Redd, and Brown’s recording made the charts that year. It remained a seasonal favorite each year throughout the 1960s, reaching #1 on a Christmas Singles chart in 1972. Six years later, as The Eagles were struggling to come up with the follow-up to their mega-platinum 1977 LP “Hotel California,” their label insisted they select something to release for the lucrative Christmas season. Glenn Frey, a blues rock aficionado, had always liked Brown’s song, so he brought it to the group’s attention, and they polished off a solid cover version, which reached #18 in 1978, the first Christmas single to make the Top 20 on the pop charts since Roy Orbison’s “Pretty Paper” in 1963. Bon Jovi had a popular version of “Please Be Home for Christmas” included on “A Very Special Christmas 2” collection in 1992.

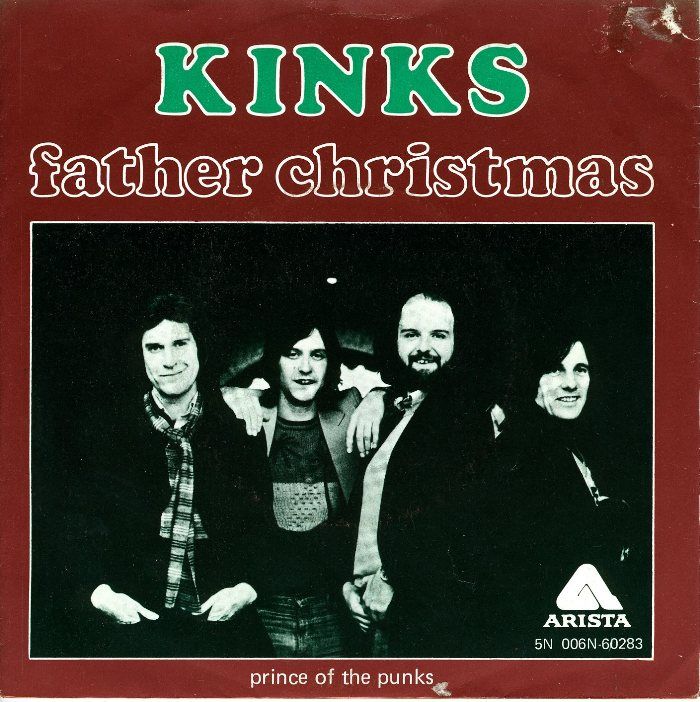

“Father Christmas,” The Kinks, 1977

The hardest rocking tune on this list, and the least Christmassy, is this angry diatribe by Ray Davies and The Kinks. They wrote this and recorded it in 1977, during punk rock’s heyday in England, as a screed about the unfair class system prevalent there, where rich kids got many Christmas presents while poor kids got none. Davies sings of a gang of poor kids beating up on a department store Santa Claus, telling him they want his money, not toys. “Father Christmas, give us some money, /Don’t mess around with those silly toys, /We’ll beat you up if you don’t hand it over, /We want your bread so don’t make us annoyed, /Give all the toys to the little rich boys!…” Many punk and hard rock bands have covered it in recent years, from Green Day and Bad Religion to Warrant and Smash Mouth.

“Little Saint Nick,” The Beach Boys, 1963

It’s no secret to Beach Boys fans that there’s plenty of bad blood between Brian Wilson and cousin Mike Love that has kept the band in different camps on and off for decades. Sometimes the differences were artistic; for example, Love didn’t care for Wilson’s new direction with the songs on the universally praised 1966 LP “Pet Sounds.” Love also took exception to being excluded from songwriting credit for some of the classics in the band’s lucrative early catalog. The Christmas single “Little Saint Nick,” recorded in 1963 and borrowing heavily from their earlier Wilson/Love tune “Little Deuce Coupe,” was one such bone of contention. The original single indicates Wilson as its sole writer, but Love won back royalties and co-writer credit in a 1993 lawsuit. The song appeared on “The Beach Boys’ Christmas Album” in 1964 along with a dozen covers of traditional carols.

“Happy Xmas (War is Over),” John Lennon and Yoko Ono, 1971

Like so many Lennon tracks of his early solo period (“Cold Turkey,” “Instant Karma,” “Power to the People”), this unique “holiday protest song” was written and recorded quickly, this time to capitalize on the 1971 Yuletide season, but they were late getting it out. “Happy Christmas (War is Over)” never got past #42 in the US that year, but it was a Top Ten hit in Europe and #4 in the UK when released there for the 1972 holiday season. The song, which utilized the basic structure of the English folk song “Stewball,” was designed as an anti-war anthem mixed with untraditional Christmas tidings (“And so this is Christmas, and what have you done?…”), bringing in the “War is over if you want it” theme from past protests. John and Yoko used session musicians Nicky Hopkins on piano and Jim Keltner on drums, and brought in the Harlem Community Children’s Choir to add vocals to the chorus, all produced by Phil Spector. Following Lennon’s death in 1980, the track soared to iconic status and has been covered by dozens of other artists.

“A-Soalin’,” Peter Paul & Mary, 1964

PP&M did a nice little trick in 1963 when they took a traditional English folk song, added a new verse by Paul Stookey with Christmas references and part of the “God Rest Ye Merry Gentlemen” melody, and voila! A Christmas song for their repertoire. It’s a simply stunning performance which appears on their “Peter Paul and Mary In Concert” double live album in 1964 when the trio seamlessly blended two acoustic guitars and their three voices. Lyrically, it sounds like it’s from some sort of soundtrack for a Charles Dickens tale. “A-Soalin'” is a variation on “A-Wassailing,” which is the practice of going door to door, singing a song and getting a small gift in return. These gifts were often fruit, candy or “soul-cakes” in memory of recently departed souls of family members. PP&M’s live recording in Paris in 1965 is on YouTube and should definitely be on your must-see holiday viewing list. https://youtu.be/nABowLcQlHc?si=62KmOGGuuz4K-rB7

“Song for a Winter’s Night,” Gordon Lightfoot, 1967

Not so much a Christmas song as a nod to wintertime, its subtle use of sleigh bells evokes fond memories of Christmases from the ’60s and ’70s, when I first heard it. Ironically, Lightfoot wrote and recorded “Song For a Winter’s Night” on a hot summer night in Cleveland while .he was there on a US tour in 1967. He was missing his wife, and his thoughts turned to winter in Toronto where they had met years earlier. It appeared on his second album, “The Way I Feel,” and was then one of several songs Lightfoot re-recorded in 1975 when he assembled the tracks for his “Gord’s Gold” greatest hits collection, which is the one you’re hearing on my playlist.

“Christmas Song” and “Another Christmas Song,” Jethro Tull, 1969 and 1989

Of all the British rock artists of the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s, none has written and recorded as much Christmas-related material as Jethro Tull. Leader Ian Anderson is a self-confessed Yuletide romantic, and early in the group’s career, he wrote “Christmas Song,” which uses traditional imagery of “Royal David city” and cattle sheds, but also reprimands us about “stuffing yourselves at the Christmas parties” and reminds us that “the Christmas spirit is not what you drink.” In the late ’80s, he wrote what amounts to a sequel, “Another Christmas Song,” which centers on a dying patrician who yearns for his estranged family to gather ’round one last time to celebrate the holidays. Both of these melodic, poignant tracks were re-recorded and included on “The Jethro Tull Christmas Album,” released in 2003.

“River,” Joni Mitchell, 1971

Deftly weaving in multiple musical phrases from “Jingle Bells” in both the introduction and the ending, Joni Mitchell created a marvelous piece that is regarded by many as a Christmas-related song, even though it’s actually more about the sorrowful breakup of a relationship she’d been having with Graham Nash. Her Canadian roots are evident in the recurring line about how “I wish I had a river I could skate away on.” Several of my close friends and family members share my fondness for this one, which appeared on her universally praised 1971 album “Blue.” I can’t fail to mention that my daughter Emily recorded a gorgeous cover of “River” several years ago with two musical colleagues, and it’s available on YouTube for your viewing pleasure: https://youtu.be/nk_kYn7x0yI?si=F0bsPg5EvWQ61n3v

“Merry Christmas Baby,” Elvis Presley, 1971

Lou Baxter and Johnny Moore came up with this beauty back in 1947, and dozens of versions have been recorded since then, from Bruce Springsteen to Otis Redding, from Melissa Etheridge to B.B. King. I’m torn between Elvis’s smokin’ hot rendition from his 1971 Christmas album “Elvis Sings The Wonderful World of Christmas” and the sensual blues cover by Natalie Cole from her “Holly & Ivy” 1994 holiday collection. Pretty much any version of this song is worthy of inclusion on your holiday mix, but in the end, you gotta go with Elvis. It was recorded as an extended 8-minute jam but edited down to a still-robust 5:44 for the album.

“Pretty Paper,” Roy Orbison, 1963

In the late ’50s and early ’60s, Willie Nelson struggled mightily to find a major label to sign him as a recording artist. In the meantime, he wrote songs which sometimes were made into hits by other artists. Most famously, he wrote “Crazy” for Patsy Cline, “Funny How Time Slips Away” for Billy Walker and “Pretty Paper” for Roy Orbison. Nelson was inspired by a disabled man he knew in Texas who sold paper and pencils on the street corner to eke out a living, and Nelson turned it into a Christmas-themed song by singing about wrapping paper. Orbison turned it into a #15 hit in 1963, and then Nelson recorded it himself after he was signed to RCA the following year.

“Do They Know It’s Christmas?” Band Aid, 1984

This sobering holiday track was an amazing collaborative effort by the best of Britain’s pop scene at the time, including Sting, Phil Collins, Bono, the members of Duran Duran and Spandau Ballet, and Bob Geldof, who produced it and co-wrote it with Midge Ure. Geldof and his wife had seen heartbreaking footage of the starvation in Ethiopia at that time and rallied their colleagues to put together this charity single, which not only raised needed funds but sparked “We Are the World” by USA for Africa and the Live Aid event in the summer of 1985. These and other efforts helped stem the tide of misery in that part of the world. That’s what Christmas should be all about.

***********************