Long-lost songs I’m so grateful to discover

I admit it. I’m obsessed with the music of the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s.

In addition to the successful songs on the albums from those three decades, there were also many hundreds, even thousands, of deep tracks buried there, just waiting to be unearthed and discovered (or re-discovered) today in 2024. I call them “lost classics,” although some are probably too obscure to qualify as classic. They’re just GREAT SONGS I firmly believe are worthy of your attention.

I’ve posted nearly 500 of these gems, a dozen at a time, in more than 40 different blog entries since I first started “Hack’s Back Pages” in 2015. This current batch (#42 if you’re counting) is comprised of infectious uptempo tunes that just might have you boppin’ around your living room before the day is through. That’s the goal, anyway…

Oh yes: I have a heads-up to all my readers. I keep a list of songs I come across that are potential candidates to make one of my “lost classics” playlists…but I’m always looking for suggestions. If you’ve got a favorite deep track that’s been forgotten or never discovered by most people, by all means, let me know. I’m eager to hear it and put it on the list of possibilities!

*****************************

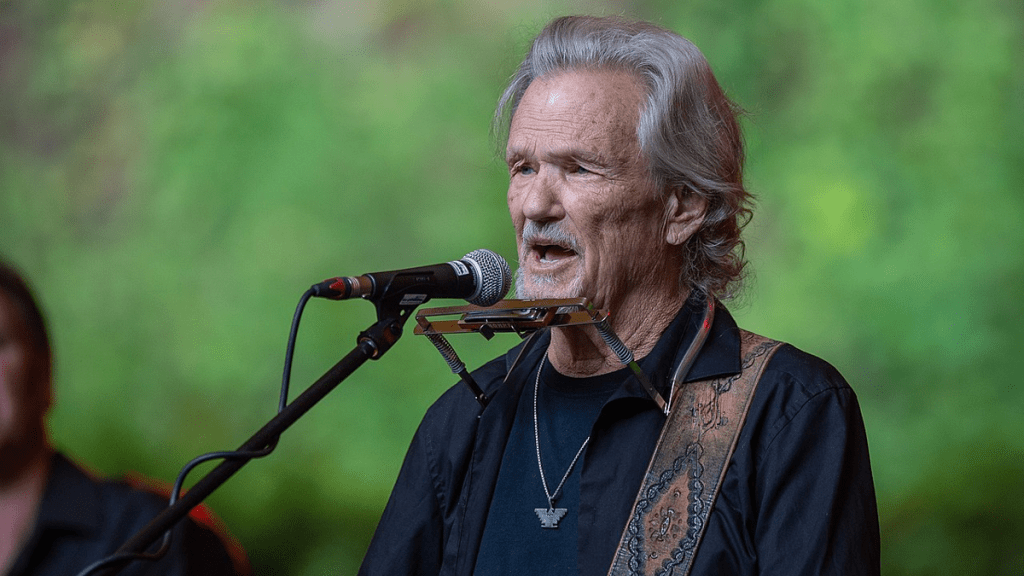

“Let It Roll,” Little Feat, 1988

One of the most underrated bands of the 1970s despite a fiercely loyal following, Little Feat was led by guitarist/songwriter Lowell George until his death in 1979, after which the group disbanded, but band members Bill Payne, Paul Barrère, Kenny Gradney and Richie Heyward continued to occasionally perform together and separately under different names. In 1988, they joined forces with singer-songwriter Craig Fuller, former founder of Pure Prairie League, and resurrected the Little Feat brand with a superb comeback LP, “Let It Roll.” I saw them tour behind Don Henley that year, turning in a fine performance, and the rollicking title track was a definite standout.

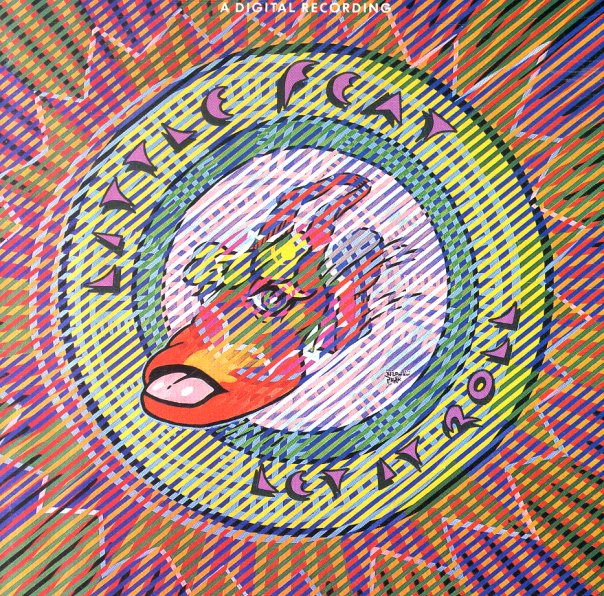

“City to City,” Gerry Rafferty, 1978

Regular readers here will know I am a big Rafferty fan, from his early work with Stealers Wheel (“Stuck in the Middle With You”) to his largely ignored later work. Most impressive in his catalog is his 1978 #1 LP “City to City,” which included his two biggest hits, “Baker Street” and “Right Down the Line,” and a lesser single, “Home and Dry.” The Scot’s husky-smooth voice and memorable melodies have appealed to me ever since, although he had an aversion to performing live, which hurt his commercial momentum. The title song “City to City” sounds like it might be about touring, but the lyrics are instead about riding the rails, as the “goodnight train is gonna carry me home.” The music, too, chugs along like a locomotive.

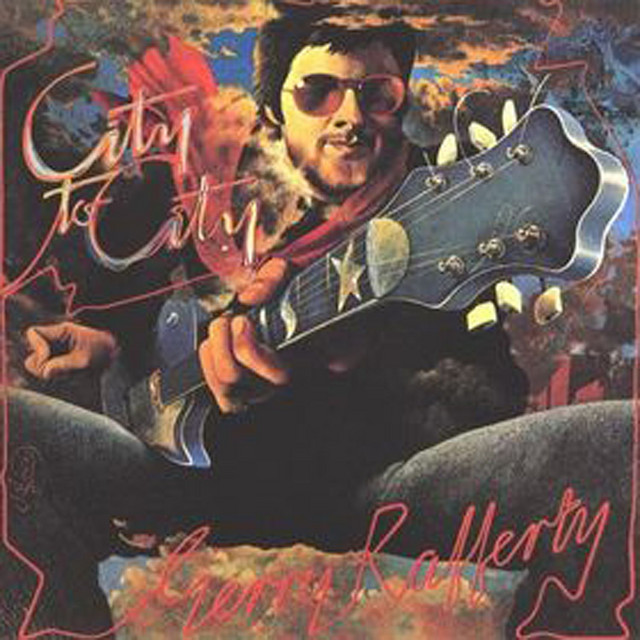

“High on Emotion,” Chris DeBurgh, 1984

British-Irish singer/songwriter DeBurgh started out in the ’70s in the art-rock genre but moved to a more commercial pop style in the ’80s, finally making inroads on both the UK and US charts in the process. The ambitious “Don’t Pay the Ferryman” crashed the Top 40 here in 1982, and by 1986, he scored a #3 hit in the US with “The Lady in Red,” which went on to be an international #1 and used in multiple film soundtracks. In between those two commercial successes, he released the appealing “Man on the Line” LP in 1984, which included great tracks like “Moonlight and Vodka” and “Much More Than This.” He just missed the Top 40 with the album’s catchy single, “High on Emotion.”

“Outskirts,” Bob Welch, 1977

Welch had been lead guitarist and singer/songwriter for Fleetwood Mac in the 1971-1974 period, keeping the band afloat between the Peter Green years and the Buckingham/Nicks multiplatinum years. Welch left to form the hard rock power trio Paris, who produced two middling albums before disbanding in 1976. The songs Welch was writing for a third Paris LP instead became his solo debut, “French Kiss,” which reached an impressive #12 on US album charts in 1977, thanks to three hit singles (“Ebony Eyes,” “Hot Love, Cold World” and a remake of his Fleetwood Mac song “Sentimental Lady”). There are other tracks here that you should know more about, including “Outskirts.”

“SWLABR,” Cream, 1967

Most of the original songs on Cream’s albums were written by bassist/vocalist Jack Bruce, with lyrics by performance poet Pete Brown, who was known for his cryptic, drug-fueled images and wordplay. “Sunshine Of Your Love,” “White Room” and “Politician” offer intriguing examples of their work, but one of the more unusual Bruce/Brown collaborations was entitled “SWLABR,” a track from their “Disraeli Gears” LP in 1967. The title is an acronym for “She Was Like A Bearded Rainbow,” and Brown said the song is about a scorned ex-girlfriend who was so jealous of his new lover that she defaced photos of her by adding a beard and moustache to them.

“Cynical Girl,” Marshall Crenshaw, 1982

With roots in classic soul and Buddy Holly rockabilly, Crenshaw emerged from Detroit in the late ’70s when he was selected to portray John Lennon in the musical “Beatlemania” on Broadway and then in a national touring company. When he made his solo debut with the “Marshall Crenshaw” album in 1982, he earned radio exposure with the irresistibly catchy “Someday, Someway.” His songs combined new wave with jangly pop that, to my ears, should’ve brought him far more commercial success than he ended up getting. “Cynical Girl,” another earworm from the first LP, inexplicably failed to make the charts as its second single. He had five albums in the ’80s that are all worth exploring.

“Everything’s Coming Our Way,” Santana, 1971

The hot new sensation of the lineup at Woodstock in 1969, Santana went on to chart at #4 for their debut LP, followed by “Abraxas” (1970), which topped the charts. For their “Santana III” album, which also peaked at #1, they continued their string of Top 40 hits as well, following “Black Magic Woman” and “One Como Va” with “Everybody’s Everything” and “No One To Depend On.” Buried near the end of Side Two was “Everything’s Coming Our Way,” one of very few Santana tracks credited to guitarist/leader Carlos Santana, and it’s a favorite of mine. The group would then shift gears in 1972 with personnel changes and a new jazz-fusion direction for a few years.

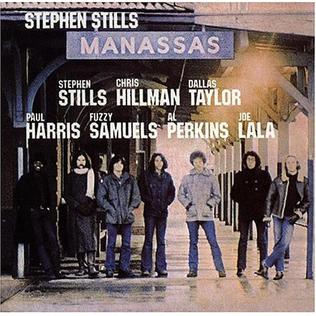

“Right Now,” Stephen Stills & Manassas, 1972

Nicknamed “Captain Manyhands” for his multiple talents as a songwriter, producer, instrumentalist and singer, Stills earned his reputation as a studio control freak during the recording of the 1972 double album by his band Manassas. The 20 songs, all written or co-written by Stills, showcased the superb musicianship of the players (Chris Hillman, Al Perkins, Joe Lala, Paul Harris, Dallas Taylor and Fuzzy Samuels) as they finessed their way through rock, country, bluegrass, Latino and blues styles. A highlight is the rock groove found on “Right Now,” with lyrics that examine his difficult relationship with Rita Coolidge, who’d been swept away by ex-bandmate Graham Nash.

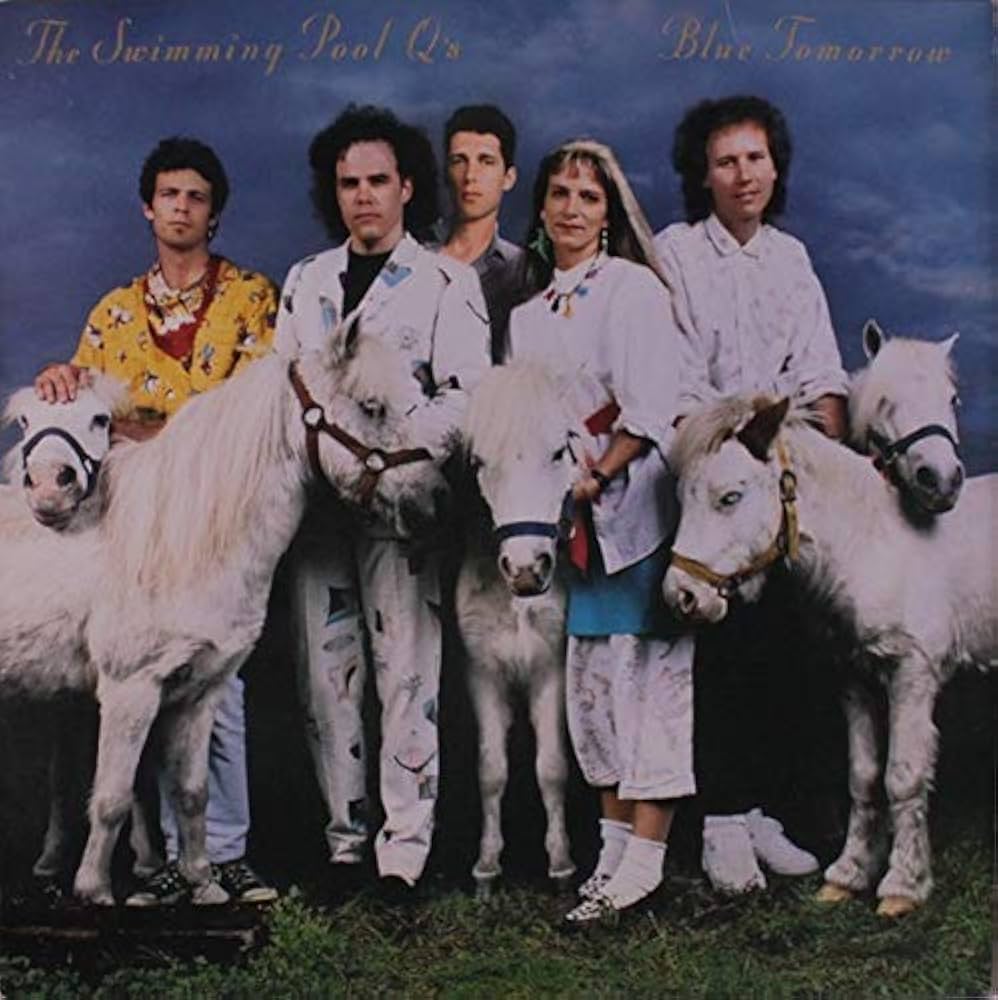

“Pretty On the Inside,” Swimming Pool Qs, 1986

From the same Athens, Georgia scene that brought us The B-52s and R.E.M. came this lesser-known band, categorized as “new wave/jangle pop.” Led by the songwriting team of multi-instrumentalist Jeff Calder and guitarist Bob Elsey and the singing of Anne Richmond Boston, The Swimming Pool Qs scored a modest hit with “Rat Bait” in 1979, which earned them slots warming up tours for Devo and The Police. They struggled on for the next decade with personnel changes and new record labels, never really making much of a dent in the charts, but in 1986, I was exposed to their “Blue Tomorrow” album, which included the compelling tune “Pretty On the Inside.”

“Waning Moon,” Peter Himmelman, 1987

Minnesota-born Himmelman is a guitarist-singer-songwriter best known for his work creating scores for such TV shows as “Bones,” “Judging Amy” and “Men in Trees” and movies like “Pyrates,” “Ash Tuesday” and “A Slipped-Down Life” in the 1990s and 2000s. He also created a well-regarded series of children’s albums designed to help kids suffering medical stress. Prior to that, he was in the indie band Sussman Lawrence in the 1980s and had a modestly successful solo career, gaining radio exposure for rock songs like “The Woman With the Strength of 10,000 Men” and especially “Waning Moon” from his 1987 LP “Gematria.” I learned about Himmelman when he warmed up for Dave Mason at a show that year.

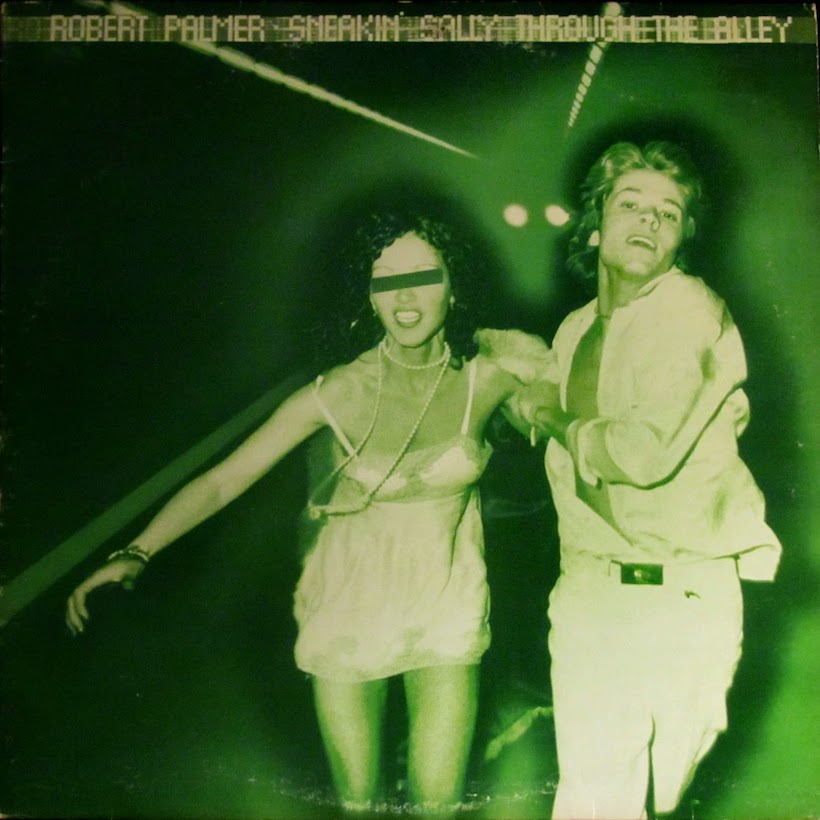

“Sneakin’ Sally Thru the Alley,” Robert Palmer, 1974

Widely known for 1980s hits like “Addicted to Love,” “I Didn’t Mean to Turn You On” and “Simply Irresistible,” stylish British singer Palmer got his start in 1974 with his underrated debut LP “Sneakin’ Sally Through the Alley,” which established his penchant for combining genres like soul, funk, rock, reggae and blues. Much of the album was recorded in New Orleans with R&B funk band The Meters, who were leery at first of Palmer’s British roots until he started singing. Legendary New Orleans musician/producer Allen Toussaint wrote the infectious title track, which features an indelible bass line by George Porter Jr. and keyboards by Art Neville.

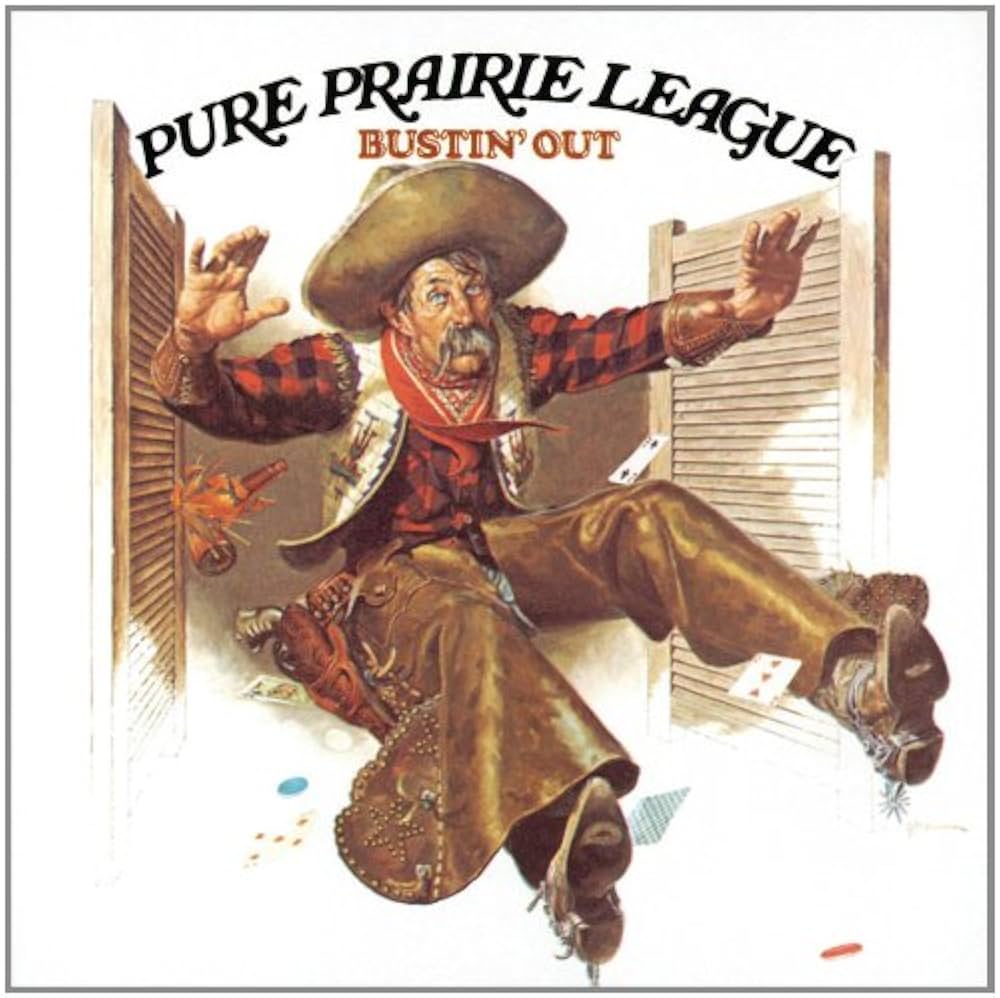

“Call Me, Tell Me,” Pure Prairie League, 1972

This popular country rock band was founded in 1970 in Ohio, with singer-songwriter-guitarists Craig Fuller and George Ed Powell leading the charge. Personnel changes between their first and second albums in 1972 hurt what little momentum they had, but Fuller’s iconic tune “Amie” picked up steam on college radio and finally became a hit in the spring of 1975. Meanwhile, the album it came from, “Bustin’ Out,” was one of the great unsung country rock albums of the ’70s, with songs like “Early Morning Riser,” “Falling In and Out of Love” and “Boulder Skies.” I’m partial to the album closer, “Call Me, Tell Me,” which features a spirited strings arrangement by (of all people) David Bowie’s then-guitarist, Mick Ronson.

******************************