Blow those horns, ’cause it sounds like victory

If you analyze the instrumentation of most classic rock songs, you most often notice the guitars (electric and/or acoustic), the keyboards, and the bass/drums of the rhythm section. Lead and background vocals, too, play a key role — sometimes THE key role — in a song’s overall mix.

But something that always makes me sit up and take notice is when pop songs have used bright, punchy, in-your-face horns. Not just a lone saxophone, although I adore the mood a sax brings to virtually every song in which it’s heard. I’m talking about rock bands with horn sections — trumpet(s), trombone and sax — that come bursting in and take a tune to an entirely different level.

Back in the ’30s, ’40s and early ’50s, before rock and roll became a defined genre, horn sections were heard all the time in big band, swing, blues and boogie-woogie recordings and in live performances. Benny Goodman, Duke Ellington, Louis Prima (“Jump, Jive ‘n Wail”) and Louis Jordan (“Ain’t Nobody Here But Us Chickens”) and other big-band leaders of that era liberally used full horn sections to underscore the vibrant rhythms provided by the other instruments. The orchestras that accompanied crooners like Frank Sinatra and Dean Martin were fond of employing brassy horns on certain uptempo tracks like “Birth of the Blues” and “Ain’t That a Kick in the Head.”

The advent of rock and roll brought the two-guitars-bass-drums lineup to the forefront of pop music, first with Elvis Presley and later popularized by The Beatles and other groups on both side of the pond, which relegated horns to the back burner (or off the stovetop entirely) for a while. But there were always exceptions like Fats Domino’s “Blueberry Hill,” Ray Charles’s “Hallelujah I Love Her So” and Sam Cooke’s “Twistin’ the Night Away.”

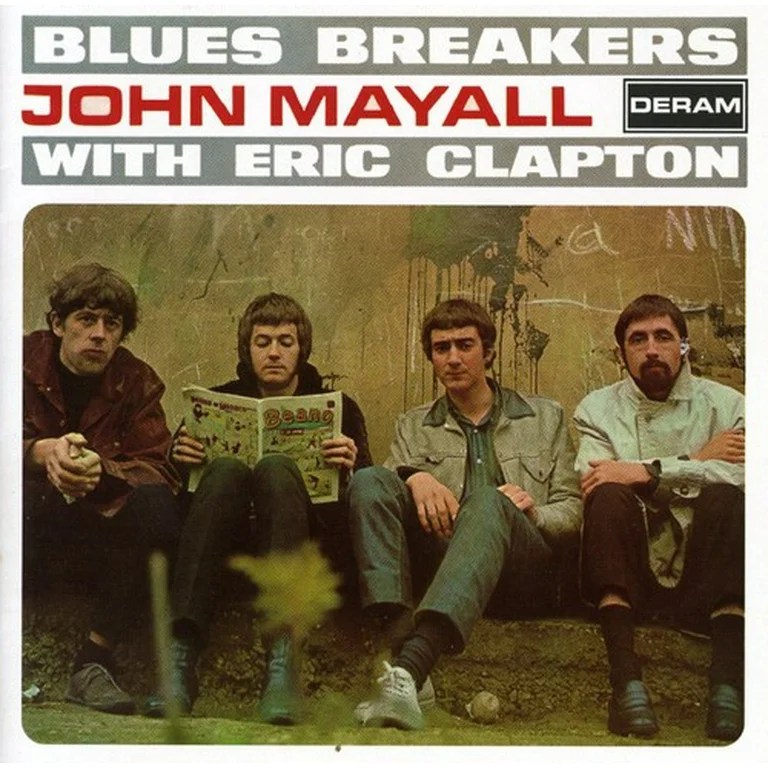

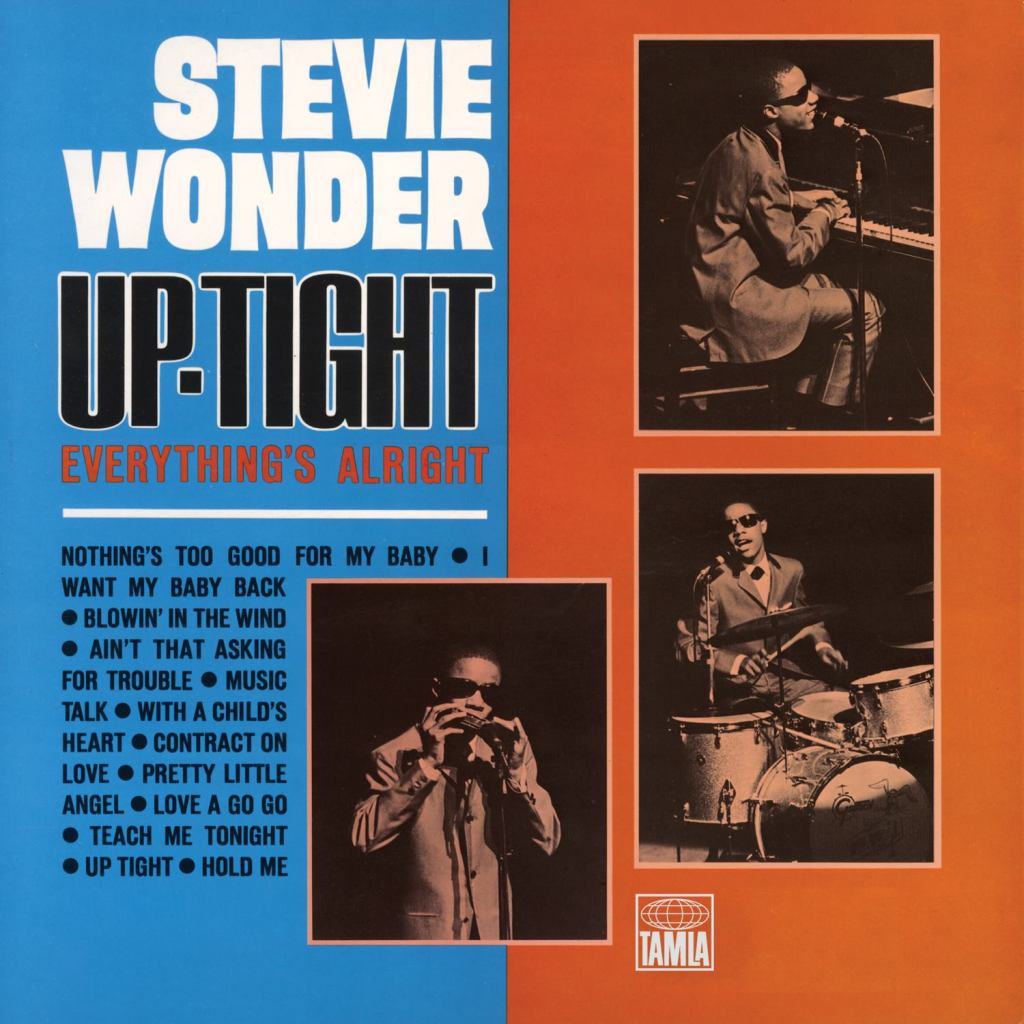

In the rhythm-and-blues arena, horns were often still featured in the hits coming out of Motown (Stevie Wonder’s “Uptight,” The Temptations’ “Get Ready”) as well as on the great James Brown’s iconic 1965 hits “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” and “I Got You (I Feel Good).” Horns were even more prevalent on the “Southern soul” songs that came from artists on the Atlantic and Stax labels in Memphis — Sam & Dave’s “Soul Man,” Wilson Pickett’s “Land of a Thousand Dances,” Eddie Floyd’s “Knock on Wood,” The Bar-Kays’ “Soul Finger” and plenty more.

As rock music began diversifying into sub-categories (country rock, acid rock, progressive rock), one of those genres was jazz rock, which reintroduced horns into the picture in a novel way, most notably by two groups: Blood, Sweat & Tears and Chicago. These bands made horns more central to the arrangements, providing instrumental showcases for both solo and ensemble playing influenced by the big-band tradition in jazz.

When BS&T founder Al Kooper sought to merge jazz and rock on BS&T’s 1968 debut, “Child is Father to the Man,” he recruited seasoned jazz musicians to comprise the all-important horn section. “I Can’t Quit Her” made a modest impact, but their second release, the multiplatinum “Blood Sweat & Tears,” featured huge hits (“You’ve Made Me So Very Happy,” “Spinning Wheel”) that put horns prominently in the Top Ten of US pop charts in 1969.

Following on their heels was the seven-man group originally called Chicago Transit Authority, which sported a three-man horn section of classically trained musicians who were headed for careers in the symphony until they were bitten by the rock and roll bug. Chicago’s star took a little longer to rise, but when “Make Me Smile” went Top Ten in 1970, their record company wisely returned to their overlooked 1969 debut and re-released tracks (“Does Anybody Really Know What Time It Is,” “Questions 67 and 68”) that had Chicago’s mighty horn section re-appearing on the charts every couple of months.

Thanks to the popularity of these two horns-dominant artists, a host of one-hit copycats saw fit to piggyback on the horns craze in 1970-1971 and had isolated successes of their own. Most notable among these were “Vehicle” by The Ides of March, “Get It On” by Chase, “One Fine Morning” by Lighthouse and “I’m Doin’ Fine Now” by New York City. Each of these offered huge blasts of horns that carried or augmented the melodies and greatly enhanced their mainstream appeal.

Truth be told, though, horns DID occasionally show up in mid-’60s pop. In particular, The Buckinghams had three Top Ten hits in 1967 (“Kind of a Drag,” “Mercy Mercy Mercy,” “Don’t You Care”) all of which featured prominent horns. Other classic hit singles that made credible use of horns included “Bend Me Shape Me” by The American Breed, “She’d Rather Be With Me” by The Turtles and “More Today Than Yesterday” by The Spiral Starecase. The Beatles’ obvious R&B tribute “Got to Get You Into My Life” was awash in horns, and Sly and the Family Stone’s horns took over on hits like “Dance to the Music” and “Stand!” Even acoustic acts like Simon and Garfunkel and James Taylor broke out the horns to accentuate 1970 album cuts like “Keep the Customer Satisfied” and “Steamroller Blues.”

The East Bay region of San Francisco seemed to incubate bands with horn sections, from the mighty Tower of Power (“So Very Hard to Go,” “This Time It’s Real”) and the Full-Tilt Boogie Band on Janis Joplin’s “Kozmic Blues” LP (“Try Just a Little Bit Harder”) to the largely unknown Cold Blood (“You Got Me Hummin'”) and Myrth (“Don’t Pity the Man”). Santana’s Latin groove sometimes threw in horns to spice things up (“Everybody’s Everything”), as did Joe Cocker in his “Mad Dogs and Englishmen” phase (“The Letter”) and even The Rolling Stones in their “Sticky Fingers” period (“Bitch”).

England contributed a couple horn-dominant outfits of their own — Osibisa (“Music For Gong Gong”) and If (“You In Your Small Corner”) — although they attracted only cult audiences in the US.

By the mid-’70s, the use of horn sections became more widespread again. Billy Preston (“Will It Go Round in Circles”), Earth Wind and Fire (“Sing a Song,” “September”) and Average White Band (“Work to Do,” “Pick Up the Pieces”) enjoyed #1 singles and albums carried by exuberant horn parts, as did glaringly underrated groups like Southside Johnny and The Asbury Jukes (“The Fever,” “Talk to Me”). Some rockers like The Doobie Brothers (“Don’t Start Me to Talkin'”), Steely Dan (“My Old School”), Bruce Springsteen (“Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out”) and Boz Scaggs (“You Make It So Hard to Say No”) presented superb horn charts to beef up the arrangements of individual tracks.

Disco and dance music of the late ’70s tended to prefer layers of strings, but horns were all over the work of The Village People (“Y.M.C.A.”) and Rick James (“Give It To Me Baby”). When John Belushi and Dan Aykroyd turned a Saturday Night Live skit into a functioning band and a feature film with The Blues Brothers, a horn section drove their best numbers, like their collaboration with Aretha Franklin on a relentless cover of “Think.”

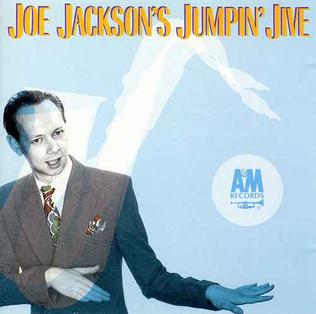

The New Wave movement of the ’80s didn’t exactly embrace horns, but there were superb songs throughout that decade that used trumpets and saxes to great effect. Joe Jackson did an entire tribute to big band music with his revelatory “Jumpin’ Jive” LP in 1981, followed by the 1984 horns hit, “You Can’t Get What You Want (‘Til You Know What You Want),” while Phil Collins made liberal use of the EW&F horn section on his solo work (“I Missed Again”) and a few tracks with Genesis as well. In 1986, Peter Gabriel and Billy Joel used killer horns on “Sledgehammer” and “Big Man on Mulberry Street,” respectively, while Paul Simon had fun with horns on “Late in the Evening” and “You Can Call Me Al.”

The ’90s brought still more revivals of horn-dominant music. Country artist Lyle Lovett demonstrated his passion for swing, blues and jazz when he released “Lyle Lovett and His Large Band” in 1989, and offered many recordings like “That’s Right (You’re Not From Texas)” with that horns-heavy outfit. Rockabilly guitarist Brian Setzer of The Stray Cats put together a touring/recording band called The Brian Setzer Orchestra that had as many as five horn players on stage and in the studio doing swing classics as well as originals like “The Dirty Boogie.” The Cherry Poppin’ Daddies took a similar although less successful approach with “Zoot Suit Riot.”

The presence of horns in pop/rock music remains a factor in the 21st Century. The full-throated R&B of the Nashville band LUTHI utilizes horns on its slow groove and uptempo numbers (“Stranger”) alike; and I was recently turned on to the lively music of Nathaniel Rateliff and The Night Sweats, whose horn section carries some of their best tracks (“I Need Never Get Old”).

There are many dozens of other examples of excellent use of horn sections in rock music, but I’ve cited the more obvious ones as well as a few personal favorites. The robust Spotify playlist below, I hope, will be an enjoyable listen that’s designed to get you up out of your chair and moving around your kitchen, living room or dance floor!

***************************