What was your best concert experience?

If you’re passionate about music, you’ve had moments in your life when listening to a song or an album, or attending a concert, has taken you to another place that shakes you to your very core. In particular, a rock ‘n roll show can be an almost spiritual experience. If you’re really really lucky, there are times when the artist, the venue, the sound quality, the light show, the audience response, the set list, and the performance all merge to create a memory that’s pretty much perfect, even life-changing.

I’ve seen upwards of 400 concerts in my life, well above average even for most music fans, partly because I once reviewed concerts for a living. These shows, as one might expect, have been everything from spectacular to abysmal. I’ve heard great bands in horrible halls, and ho-hum artists in excellent clubs. I’ve seen outstanding performances in front of rude audiences. I’ve heard extraordinary set lists played through crappy sound systems. It can be very frustrating.

Once in a while, though — maybe once in a lifetime — everything gels. All the elements come together to create an evening you’ll never ever forget.

My night was August 10, 1975. I was 20, and I was with a handful of my close friends. We were among the 2,500 or so who assembled at the old Allen Theatre, a formerly grand 1920s-era movie house in downtown Cleveland, Ohio, and we were there to feast our eyes and ears on Bruce Springsteen, the new messiah of rock ‘n’ roll.

At that point, Bruce was still a relative unknown. He was more of a cult attraction. He certainly wasn’t “The Boss” yet. His first two albums had performed badly on the charts, even though they were chock full of amazingly vibrant recordings of compelling, original songs. He had a following in his native New Jersey and a few other pockets, mostly on the East Coast, but most everywhere else, the reaction was “Bruce who?” He had reached the “make or break” point with his record company. Some at Columbia Records wanted to drop him from the label; others were still in his camp but conceded the time had come when he had to put up or shut up. He had “one last chance to make it real,” as he sang on his soon-to-be-classic “Thunder Road.”

I had first heard of Springsteen only two months earlier, in June, when I invited my old high school buddies to convene at my house one night to have a few beers and share the albums we’d turned on to at our colleges the previous semester. My friend Carp, who attended Trinity College in Hartford, Connecticut, showed up and said, “Everyone else can go ahead and play whatever they brought. I want to go last.” Okay, fine, we said, and we took turns exposing the group to songs by artists like Ambrosia, Jesse Colin Young, Camel, and Peter Frampton. Then Carp stood up and approached the turntable. He lowered the needle on track two, side two of “The Wild, The Innocent and the E Street Shuffle,” and an eight-minute piece of unrestrained exuberance called “Rosalita” came roaring out.

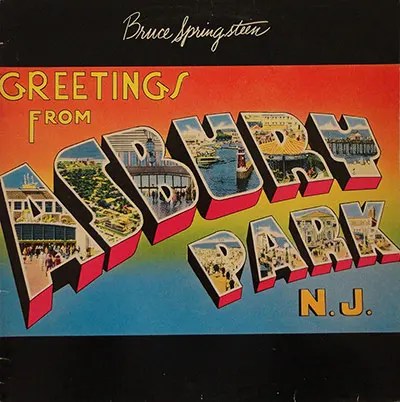

When the song ended, every single person in the room was struggling to pick up their jaws from the floor. “Holy SHIT!” we said, almost in unison. Then I asked, “Is the whole album that good?” And he flipped the album over and treated us to another over-the-top masterpiece called “Kitty’s Back.” I bought the album the next day. And, in the record store bin, I found another Springsteen album, the earlier LP “Greetings From Asbury Park, N.J.,” and I figured, what the hell, and bought that one too. Within a week, I knew the words to almost every song on both albums, and boy, was I hooked on this guy.

Kid Leo, the streetwise DJ on Cleveland’s iconic FM station WMMS, played Bruce’s stuff all the time, especially the monumental new single, “Born to Run,” which he would air every Friday at four minutes ’til 6:00 to sign off his drive-time shift. Over the previous 18 months, Springsteen had damn near broken the backs of his fabulous group, The E Street Band, as they struggled in poverty working in three different studios recording what they hoped would be their definitive statement, the album that would bring them the fame they felt they deserved.

Sure enough, “Born to Run” turned out to be that album. But it wouldn’t be released until August 25th, two weeks later, so when my friends and I walked into the Allen Theatre to hear him perform “Rosalita” and the material from those first two albums, we were unfamiliar with the wonders of “Backstreets” and “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out” and “She’s the One” and “Jungleland.”

Cleveland, a blue-collar rock ‘n roll town, had been one of the cities that supported Bruce early on, and he appreciated it. (Indeed, three years later, he made a triumphant return to Northeast Ohio to play for the WMMS 10th Anniversary Show at the tiny Agora Ballroom in August 1978, a mind-blowing gig that was released in CD and on-line formats in 2014.) But in the summer of 1975, he was booked at the Allen, just three nights before the legendary five-night stand at The Bottom Line in New York City, where he cemented his reputation with critics as one of rock ‘n roll’s finest-ever live performers.

Our expectations were high when we took our seats in the 18th row. The venue wasn’t too big, which meant it would be intimate enough to provide the opportunity for a genuine bond between audience and artist. We knew from previous shows there that the acoustics were decent and the sound should be reasonably good. We loved the albums, and we’d heard he was one of those “you’ve gotta see him live” performers, so we were pretty sure this was going to be great.

Well.

Bruce Springsteen and The E Street Band proceeded to rearrange our brain cells, decalcify our spinal columns, and send us into the stratosphere with an incendiary rock and roll performance of passionate music. It was sweaty, it was vital, and it was electrifying.

They played most of the tracks from the albums we knew, and a handful of songs from the new-to-us “Born to Run” LP, plus some vintage rock ‘n roll tracks like “Havin’ a Party” and “Up on the Roof.” As the lyrics say in “Growin’ Up,” Springsteen “commanded the night brigade” with a cocky/confident look that combined pirate with street punk, complete with scruffy beard, newsboy cap, torn undershirt, leather jacket, jeans and sneakers. He was young, hungry and eager to please, and it showed. He scampered all over the stage like a chimpanzee in heat, bringing the crowd to a frenzy that rarely dissipated.

Springsteen leaned onto the broad shoulders of his sax player Clarence Clemons, “The Big Man,” just like on the soon-to-be-iconic album cover that hadn’t appeared yet. He offered up early lyric-heavy tunes like “Spirits in the Night,” “Growin’ Up” and “It’s Hard to Be a Saint in the City,” embellishing the recorded versions with spoken introductions and extended solos. He and The E Street Band captured our attention with “Incident on 57th Street,” “New York City Serenade” and an explosive “Kitty’s Back,” three dramatic street-opera pieces from “E Street Shuffle.” He treated us to intimate arrangements of “For You” and “Thunder Road,” alone at the piano. He obliterated us with a killer rendition of “Rosalita,” when Clemons took the microphone off its stand and dropped it INTO his saxophone, blowing the roof off the joint. And most of all, he blew our minds with the new material from “Born to Run,” most notably “She’s the One,” “Tenth Avenue Freeze-Out” and the title track, which would become among his most cherished in-concert songs for many years to come.

After multiple encores, feeling totally drained and exhilarated, I vividly remember as we came spilling out of the theater’s side exit into an alley. That delirious crowd of Cleveland rock fans were total strangers, but we danced and sang and pumped our fists in the air like lifelong friends as we chanted, “Tramps like us, baby, we were born to run!!” We knew we had been part of something incredibly special, and we didn’t want the night to end. And it didn’t. My friends and I piled into the car and cranked up “Rosalita” one more time for the ride home, rolling down the windows and yelling out the words at the top of our lungs. And I still sing it at the top of my lungs to this day.

Every music fan should be lucky enough to live through something like that.

*************************

It’s quite a coincidence that a decade or so later, I became friends with Gary Sikorski, a dear friend of my wife, who had worked as an usher at the Allen Theatre during that period. He also saw Springsteen for the first time that night, and was similarly transformed by the experience. He recalled being in the empty hall before the show during soundcheck, sitting high up in the balcony, when The Boss, holding a remote mic, came up to hear how it sounded from the nosebleed seats. “He sat down next to me and sang right at me for a few moments before wandering off to check other areas of the auditorium,” he recalled. Later on, midway through the concert, “My duties as usher allowed me access to the front of the stage, and that’s where I stood for the entire second half. At one point, feeling exhausted and overwhelmed by the music, I fell to my knees. I still remember the smell of the carpet. I was never the same after seeing that show. I became what you would call a disciple of Bruce, and have had the chance to meet him and hang out with him a few times. I’ve since seen him in concert well over 200 times, I’ve lost track. He’s the absolute best there is, and no one else is even in second place!”

*************************

The Spotify playlist recreates, as best I can assemble, the songs we heard at the Allen that night. The live renditions here are from performances in Los Angeles in October 1975 and in London in November, a couple of months after the Cleveland show, which means they’re reasonably faithful to what we heard in August. The rest are the original studio recordings.