I’d trade all my tomorrows for a single yesterday

The popular music world is populated by many musicians who were brought up in musical households with parents who encouraged their interest in artistic expression.

But there are also hundreds of songwriters and musical artists whose parents had other plans for their children and strongly discouraged or even forbade them from pursuing a life in the musical arts.

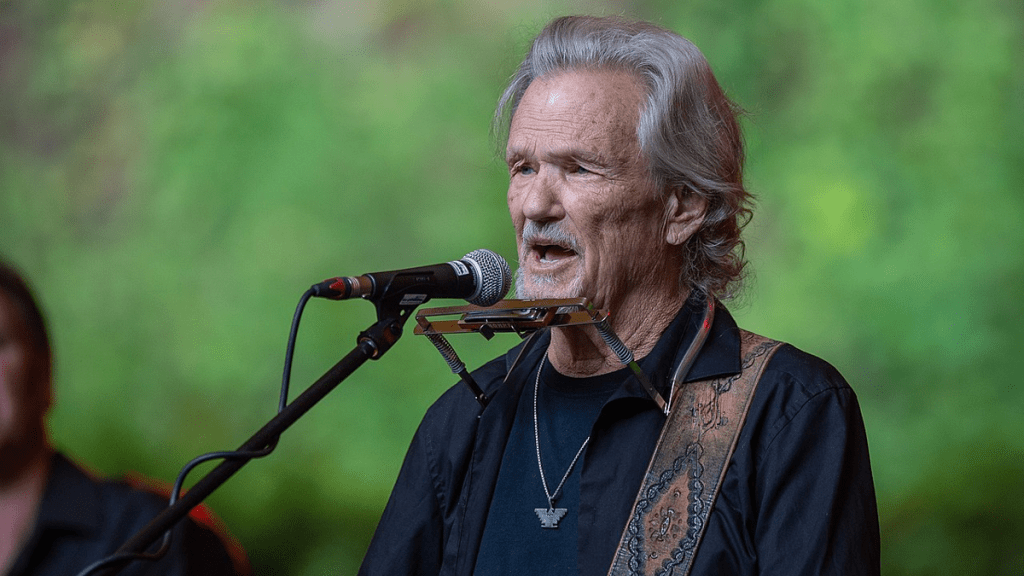

If Kris Kristofferson‘s parents had had their way, we would have never experienced the pleasure of hearing his wondrous songs or viewing his compelling film performances.

Kristofferson’s father Lars was a major general in the US Air Force, and he wanted his son to follow his footsteps into a lifelong career in the military. For a while, it looked like that might happen when, at age 24, Kristofferson accepted a commission as a lieutenant in the Army and became a helicopter pilot, eventually reaching the rank of captain in 1965. Also a gifted writer, Kristofferson was slated to teach English at West Point, but he declined and instead traded that life to pursue his dream to become a country songwriter in Nashville. His parents were scandalized and disowned him for a while.

“Not many cats I knew bailed out like I did,” Mr. Kristofferson said in a 1970 interview. “When I made the break, I didn’t realize how much I was shocking my folks, because I always thought they knew I was going to be a writer. But I think they thought a writer was a guy in tweeds with a pipe. So I quit and didn’t hear from them for a while. I sure wouldn’t want to go through it again, but it’s part of who I am.”

Kristofferson, who died September 28 at age 88, didn’t experience a seamless transition from military man to songwriter, but he had the innate talent and a lot of perseverance. He had graduated with honors with a degree in literature from Pomona College, and had prizewinning entries in a collegiate short-story contest sponsored by The Atlantic magazine before being awarded a Rhodes scholarship to study English literature at Oxford.

All that formal training didn’t translate at first in the world of country music. His early songs read like classic poetry with perfect grammar, and he had to learn to adapt, using more conversational vocabulary with vernacular terms and real-life experiences. During his time as a janitor at Columbia Records, he absorbed a lot by sneaking into the recording sessions of major artists like Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash. “I had to get better,” Kristofferson said. “I was spending every second I could hanging out and writing and bouncing off the heads of other writers.”

He developed, as a New York Times writer put it, “a keen melodic sensibility and a languid expressiveness that bore little resemblance to the straightforward Hank Williams-derived shuffles he was turning out when he first arrived in Nashville.” He continued evolving over the next few years until he garnered the attention of publishers and artists in town who were impressed with songs like “Sunday Morning Comin’ Down,” perhaps the most poignant hangover song ever written: “Well, I woke up Sunday morning with no way to hold my head that didn’t hurt, /And the beer I had for breakfast wasn’t bad, so I had one more for dessert…”

His diligence paid off. Between 1970 and 1972, the name Kristofferson seemed to be everywhere. Singer Ray Price took his ballad “For the Good Times” to #1 on the country charts and #11 on the Top 40 pop charts, and soul legend Al Green made it a staple of his shows after recording his own version. Cash registered a Country #1 with “Sunday Morning Comin’ Down” a couple months later.

Most significantly, his iconic composition “Me and Bobby McGee” (first recorded by Roger Miller in 1969 and Gordon Lightfoot in 1970) became an international #1 hit when Janis Joplin’s recording of it was released posthumously in 1971. Years later, Kristofferson said, “I remember one of my songwriter friends said, ‘You’ve got such a good song going on there. Why do you have to put that philosophy in there?’ He was referring to the line ‘Freedom’s just another word for nothing left to lose.’ It turned out to be one of the most memorable lines I ever wrote. So you’d best take your friends’ advice with a grain of salt.”

Concurrently, Kristofferson’s song “Help Me Make It Through the Night” topped country charts and reached #8 on pop charts with singer Sammi Smith’s delicate rendition, which won a Country Song of the Year Grammy for the songwriter.

All four of these songs appeared on “Kristofferson,” the songwriter’s own recording debut in 1970, but his gruff, uncultured singing voice wasn’t exactly embraced by critics or the public (one writer described it as “pitch-indifferent”). Kristofferson often knocked his own voice. “I don’t think I’m that good a singer,” he said in a 2016 interview. “I can’t think of a song that I’ve written that I don’t like the way somebody else sings it better.” Indeed, although he released more than 15 albums of his own, five of which charted reasonably well on country and pop charts, he had only one successful single, the country gospel tune “Why Me,” which peaked at #16 in 1973.

It turned out to be a fortuitous time to be a songwriter in Nashville, where Kristofferson found himself huddling with with like-minded writers such as Willie Nelson and Roger Miller. “We took it seriously enough to think that our work was important, to think that what we were creating would mean something in the big picture,” he said in a 2006 interview. “Looking back on it, I feel like it was kind of our Paris in the ’20s — real creative and real exciting, and intense.”

Kyle Young, the CEO of the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum, had this to say this past week: “Kris Kristofferson believed to his core that creativity is God-given, and that those who ignore or deflect such a holy gift are doomed to failure and unhappiness. He preached that a life of the mind gives voice to the soul, and then he created a body of work that gave voice not only to his soul but to ours. Kris’s heroes included the prize fighter Muhammad Ali, the great poet William Blake, and the ‘Hillbilly Shakespeare,’ Hank Williams. He lived his life in a way that honored and exemplified the values of each of those men, and he leaves a righteous, courageous and resounding legacy that rings with theirs.”

Author Bill Malone noted in “Country Music, U.S.A.,” the standard history of the genre, “Kristofferson’s lyrics spoke often of loneliness, alienation and pain, but they also celebrated freedom and honest relationships, and in intimate, sensuous language that had been rare to country music.”

I wholeheartedly agree. Consider these lines from his 1974 song “Shandy (The Perfect Disguise)”: “‘Cause nightmares are somebody’s daydreams, /Daydreams are somebody’s lies, /Lies ain’t no harder than telling the truth, /Truth is the perfect disguise…”

He could also be quite provocative, as in these lyrics from the title tune from his 1972 LP: “Jesus was a Capricorn, he ate organic food, /He believed in love and peace and never wore no shoes, /Long hair, beard and sandals, and a funky bunch of friends, I reckon we’d just nail him up if he came down again…”

In 1971, he developed a personal and professional relationship with singer Rita Coolidge, marrying her and recording a handful of albums with her (“Full Moon” in 1973, “Breakaway” in 1974 and “Natural Act” in 1978) that reached the Top 20 on country charts. The couple won two Grammys (Best Country Vocal Performance by a Duo) for “From the Bottle to the Bottom” in 1973 and “Lover Please” in 1975. They would divorce in 1980 but remained friends and occasionally performed together.

Said Coolidge last week, “Kris was a wonderful man and an extraordinary songwriter. He’s been a close friend of mine and the father of my daughter. We had a volatile marriage, but I have nothing but glowing things to say about him today.” In her 2016 autobiography, “Delta Lady,” she bemoaned his drinking, his verbal abuse and his infidelities, but concluded, “Everything we did was larger than life. I never laughed with anybody in my life like I did with Kris. When it was good, I was over-the-moon happy, but when it was sad, it was almost too much to bear.”

Kristofferson’s acting career took off in 1973 when Sam Peckinpaugh cast him as outlaw Billy the Kid in “Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid,” in which Coolidge also appeared. Martin Scorsese concurred that Kristofferson’s rugged good looks and magnetism lent themselves to the big screen, and cast him as the male lead alongside Ellen Burstyn in the critically acclaimed 1974 drama “Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore.”

When Barbra Streisand was unable to secure Elvis Presley as her co-star in the 1976 remake of “A Star is Born,” her next choice was Kristofferson, who won a Golden Globe for his turn as John Norman Howard, a singer on the downside of his career who ends up killing himself in a drunk-driving incident. Kristofferson, who had described himself as “a functioning alcoholic,” said he was so disturbed by the scene where Streisand’s character tends to his dead body, he quit drinking in real life. “I remember feeling that that could very easily be my wife and kids crying over me,” he said in the 1980s. “I quit drinking over that. I didn’t want to die before my daughter grew up.”

He followed that experience with “Semi-Tough,” the sports comedy film opposite Burt Reynolds and Jill Clayburgh, but his movie career suffered in 1980 when he starred in Michael Cimino’s epic Western, “Heaven’s Gate,” one of the biggest box-office disasters in Hollywood history. Kristofferson fared reasonably well in the reviews, but the movie itself was so mercilessly panned that anyone involved with it found themselves unhirable for years to come. It would be another 15 years before he regained his footing in John Sayles’ Oscar-nominated “Lone Star.”

He attracted a new generation of fans for his portrayal of mentor/father figure Abraham Whistler in Marvel’s first successful film, “Blade,” and its two sequels. Indeed, many superhero movie fans of the late 1990s and early 2000s had no idea that Kristofferson had another career as a singer-songwriter, which he found rather amusing. “I was doing a show in Sweden, and somebody backstage mentioned to me, ‘Hey Kris, there are all these kids out there saying, ‘Geez, Whistler sings?'”

When he experienced a dry spell in both acting and songwriting in the early ’80s, he found solace in his friends in the music business. Kristofferson teamed up with Waylon Jennings, Willie Nelson and Cash to record “Highwayman,” Jimmy Webb’s marvelous song about a soul with four incarnations in different places in time and history. It became a multiplatinum hit that inspired a full album by the foursome, who came to be known as The Highwaymen. They capitalized on the favorable commercial and critical response by recording more albums and touring multiple times over the next decade. Kristofferson later marvelled, “I always looked up to all of those legends, and I felt like I was kind of a kid who had climbed up on Mount Rushmore and stuck his face out there!”

He often talked about how grateful he is to the established songwriters and singers in Nashville who took him under their wing when he was new to town. In comparison, he noted, “Those shows like ‘American Idol’ are kind of scary to me. They wanted me to be on one of those panels one time, and I said it’s the last thing in the world I’d ever want to do. I would hate to have to discourage somebody.”

His legacy as a songwriter is cemented by the number and diversity of artists who have admired his material enough to record it. In addition to Johnny Cash, Janis Joplin, Ray Price, Rita Coolidge, Roger Miller, Gordon Lightfoot, Sammi Smith and Al Green, you can hear strong covers of Kristofferson songs by The Grateful Dead, Frank Sinatra, Willie Nelson, Gladys Knight and The Pips, Elvis Presley, Dolly Parton, Wilson Pickett, Charley Pride, Olivia Newton-John, Ronnie Milsap, Tina Turner, Glen Campbell, Bryan Adams, Joan Baez, Jerry Lee Lewis, Emmylou Harris, Michael Bublé and Thelma Houston.

Streisand said recently, “At a concert in 2019 at London’s Hyde Park, I asked Kris to join me on stage to sing our other ‘A Star Is Born’ duet, ‘Lost Inside Of You.’ He was as charming as ever, and the audience showered him with applause. It was a joy seeing him receive the recognition and love he so richly deserved.”

Kristofferson was married to his third wife, Lisa, for more than 40 years, from 1983 until his death. He had a total of eight children from his three marriages, and seven grandchildren. When asked about his family in 2016, he said, “When I was thirty, and a long time after that, I felt like I had to leave home to do what I had to do. Now, it’s just the opposite.”

Bypass surgery in 1999 slowed Kristofferson down, as did an extended bout with Lyme disease in the decade that followed, but he remained active into his 80s. On his final album of new material, 2013’s “Feeling Mortal,” the title song sums up Kristofferson’s feelings near the end of his life: “Here today and gone tomorrow, that’s the way it’s got to be, /God Almighty, here I am, /Am I where I ought to be? /I’ve begun to soon descend like the sun into the sea…”

**************************