We’re jammin’ in the name of the Lord

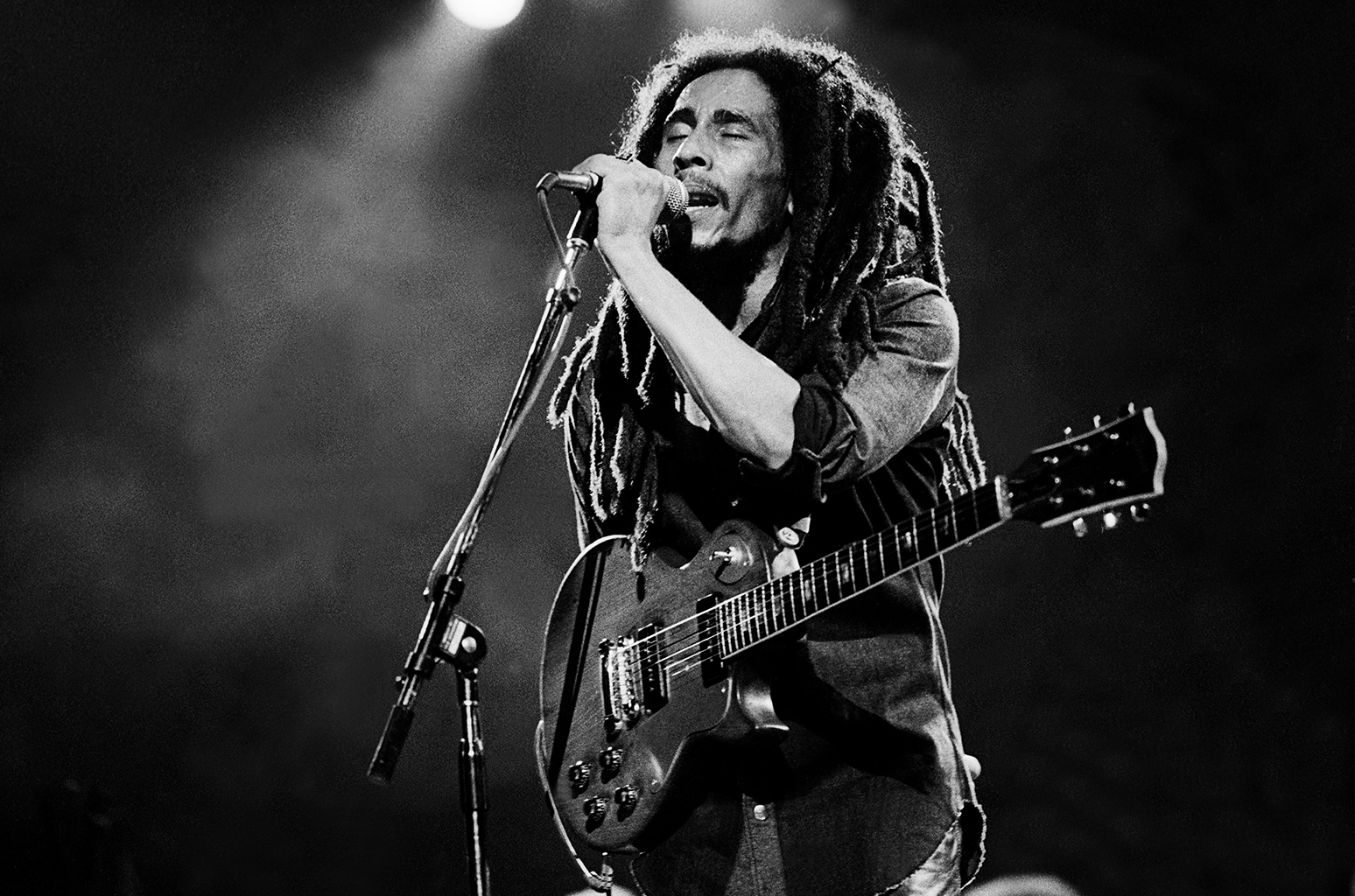

“This is my message to you: Don’t worry about a thing, ’cause every little thing gonna be all right…” — Bob Marley

*************

Insistent yet gentle offbeat rhythms. Lyrics of overwhelming positivity and confident pursuit of justice. Fiercely defiant, yet warmly exhilarating.

That, in a nutshell, is the essence of reggae music. Or, as any Jamaican bus driver will tell you: “It’s island music, mon.”

Reggae, born in Jamaica in the ’60s, blends a tantalizing hybrid of ska, mento and calypso musical strains with a powerful lyrical message that focuses on social criticism and political consciousness, and the need for positive vibes, eternal love, joy and peace. It’s most readily distinguished by its rhythmic emphasis on the offbeat, or backbeat (the second and fourth beat), instead of the downbeat (first and third beat), which characterizes most pop music styles.

Much more than many musical genres, reggae also has strong ties to religion, specifically Rastafarianism, a religious and social movement (they prefer “a way of life”) founded by Afro-Jamaicans in 1930s Jamaica primarily as a rejection of British colonialism. Its beliefs include the healing powers of copious cannabis use and hypnotic, rhythmic music “to achieve the spiritual balance necessary for a satisfying existence.”

Hmmm. Not exactly mainstream thinking in America at that time, although fringe audiences in isolated regions around the world took to it enthusiastically — both the music and the message.

Reggae first found favor outside Jamaica in the early 1970s in England, where West Indian communities in and around London helped expose music lovers to the genre there. Indeed, major British pop stars like Paul McCartney and Eric Clapton developed an interest in the island rhythms from hearing it performed by Jamaican musicians in the clubs of London.

Here in the United States, the acceptance and assimilation of reggae into the popular music market seems to have had a peculiar off-and-on history throughout the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s.

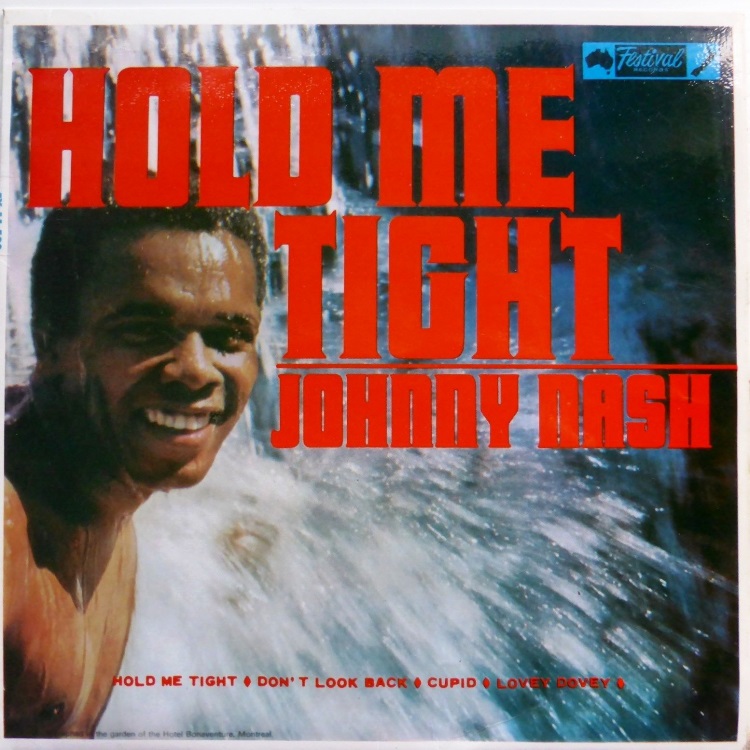

Its first appearance here, it’s generally agreed, came when an American-born artist — Johnny Nash, a Houston-based pop singer-songwriter — took his version of Jamaica’s indigenous music to #5 on the U.S. charts in 1968 with the catchy “Hold Me Tight.” But if record companies were expecting to then cash in on a flood of reggae songs and bands, it didn’t happen. (At least not yet.)

True, The Beatles, always savvy and forward-looking in their musical development, took a shot at reggae during sessions that same summer for “The White Album.” McCartney explains: “I had a friend named Jimmy who was a Nigerian conga player, and he was a happy happy guy all the time, like a philosopher to me, because he had all these great expressions about life. One of them was ‘obladi, oblada, life goes on, bra…’ I told him I loved it and was going to use it in a fun little song I was writing that used a rhythmic approach I was starting to hear from Jamaican bands in the London clubs at the time. Wonderful vibe, this music called reggae. So that’s what ‘Ob-la-di, Ob-la-da’ was, our rudimentary attempt at reggae. I don’t know if we quite got it, but we had a blast trying.” But it wasn’t a single, just one of 30 album tracks, so it didn’t achieve widespread popularity until nearly a decade later.

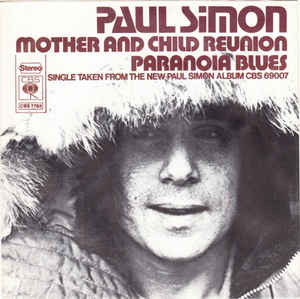

So reggae went back into hiding for a few years until the great Paul Simon, always curious about “world music” and intriguing new rhythms, visited Kingston in 1971 to record his new song “Mother and Child Reunion.” He admired reggae artists like Jimmy Cliff and Desmond Dekker and wanted to explore the music further at its source, using Jamaican musicians who instinctively knew the way it should be played. He invited Cliff’s backing group to accompany him on the recording, and the result was also a #5 hit that put reggae back in the public eye.

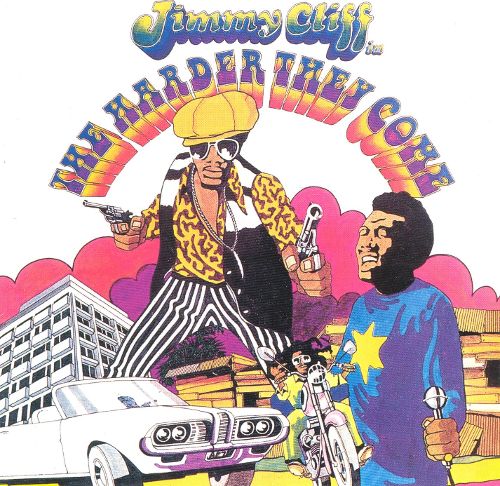

The attention Cliff gained from that connection helped him later that year when he released “The Harder They Come,” the soundtrack album to the movie of the same name (in which he also starred). The film, a crudely made crime drama, was largely ignored but later became a favorite with the midnight-movie crowd.

Then, in the fall of 1972, a reggae song finally reached #1 on the charts here (and in Canada) when Nash returned with “I Can See Clearly Now,” the most popular song in the U.S. for four straight weeks. A year later, Clapton took the plunge that inadvertently brought reggae to an entirely new level in the U.S. and elsewhere.

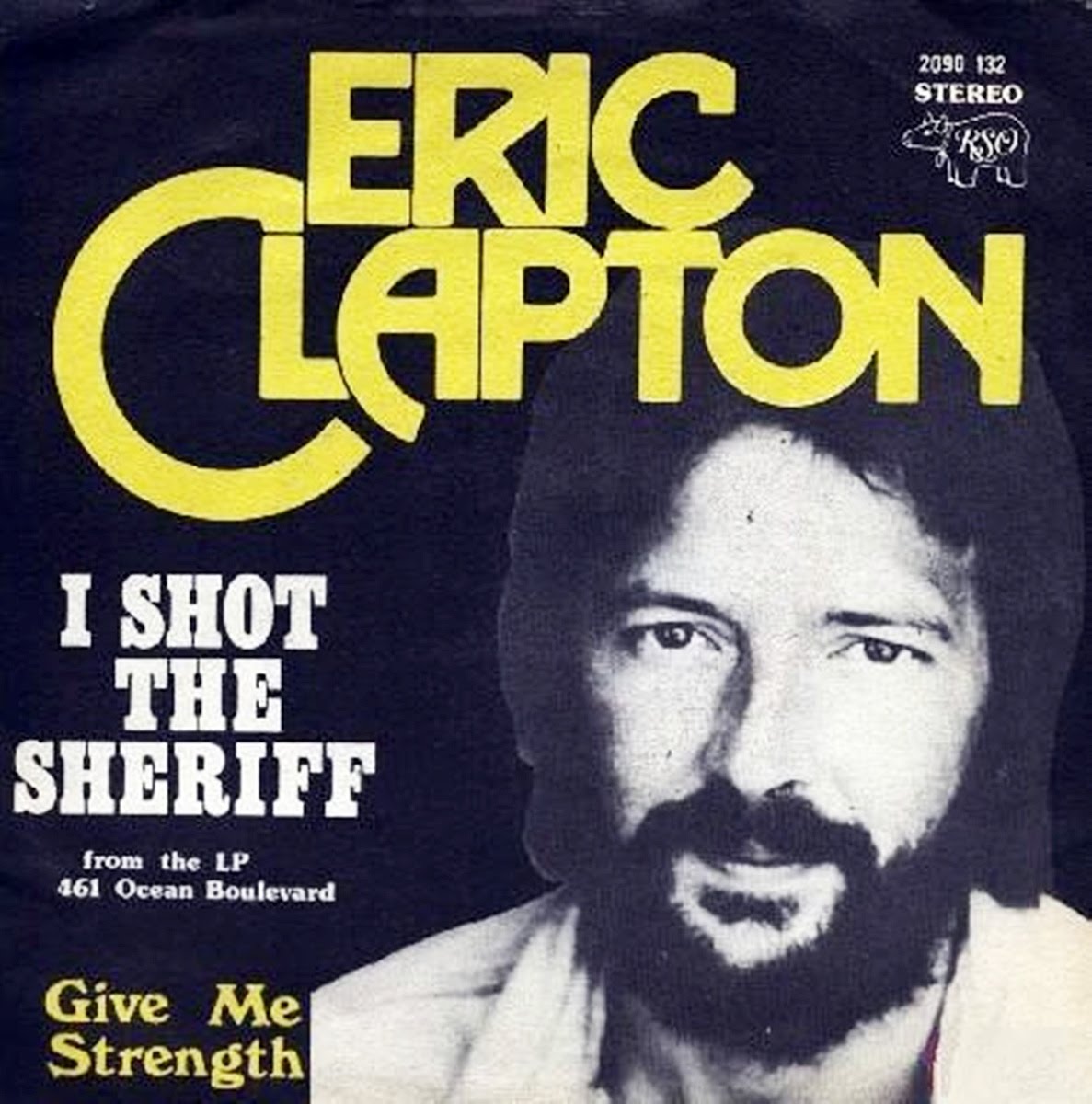

Recalled the guitarist, “We were in Miami cutting the album that became ‘461 Ocean Boulevard.’ One day, guitarist George Terry came in with an album called ‘Burnin” by Bob Marley and the Wailers, a band I’d never heard of. When he played it, I was mesmerized. George especially liked the track ‘I Shot the Sheriff’ and kept saying to me, ‘You should cut this, we could make it sound great.’ But it was hard-core reggae and I wasn’t sure we could do it justice. We did a version of it anyway, and although I didn’t say so at the time, I wasn’t that enamored with it. Ska, bluebeat and reggae were familiar to me, but it was still quite new to American musicians, and they weren’t as finicky as I was about the way it should be played — not that I really knew myself how to play it. I just knew we weren’t doing it right.

“When we got to the end of the sessions, and started to collate the songs we had, I told them I didn’t think ‘Sheriff’ should be included, as it didn’t do the Wailers’ version justice. But everyone said, ‘No, no, honestly, this is a hit.’ And sure enough, when the album was released and the record company chose it as a single, to my utter astonishment, it went straight to Number One. Though I didn’t meet Bob Marley until much later, he did call me up when the single came out and seemed pretty happy with it. I tried to ask him what the song was about, but I couldn’t understand much of his reply. I was just relieved that he liked what we had done with it.”

Marley had been a tireless devotee and champion of reggae throughout its early years of development, when his fellow Wailers (including Peter Tosh and Bunny Wailer), along with Toots and The Maytals, were the true pioneers of the genre. It was Marley, through his songwriting, singing and relentless performing, who caught the eye and ear of Chris Blackwell, founder of the seminal Island Records and a native Jamaican himself.

In Marley, Blackwell recognised the elements needed to snare the rock audience: “Rock music was always rebel music at heart, and so was reggae. I felt that demonstrating that similarity would really be the way to break Jamaican music in the U.S. But you needed someone who could be that image. When Bob walked in, it was clear to me that he really was that image.”

He signed Marley to a lucrative contract in 1973, let him loose in his studios in the Bahamas and England, and sat back and waited. The debut LP, “Catch a Fire,” marked the first time a reggae band had access to a state-of-the-art studio and were accorded the same care as their rock ‘n’ roll peers. Blackwell, hoping to create “more of a drifting, hypnotic-type feel than a rudimentary reggae rhythm,” restructured Marley’s arrangements and supervised the mixing and overdubbing.

While the album and its immediate follow-up, “Burnin’,” didn’t do much on the charts, the songs were getting better, and the rock critics and savvy listeners (especially in the UK) caught on. When Marley made his debut live appearance in London in 1975 (and the concert was later released as the “Live!” LP), he had become a major sensation there, with his iconic “No Woman, No Cry” climbing to #8 on the UK charts.

Marley had been complimentary of the efforts of Nash and Simon to expose American audiences to the world of reggae, and he publicly endorsed Clapton’s version of “Sheriff,” but he remained determined in the belief that only Jamaicans could play reggae as intended.

He told Britain’s Uncut magazine in 1976, “The real reggae must come from Jamaica. Others can go anywhere and play funk and soul, but reggae — too hard. Must have a bond with it. Reggae has to be inside you.”

By the release of “Rastaman Vibration” later that year, Marley’s music had broken through to the U.S. market. While its single, “Roots, Rock, Reggae,” stalled at #51 on the pop charts, the album soared to #8 and the 1977 followup “Exodus” (with the FM hits “Jammin’,” “Waiting in Vain” and “Three Little Birds”) was a respectable #20.

In the UK, “Exodus” stayed on the charts for an astonishing 56 consecutive weeks. Reggae’s boom there existed concurrently with the burgeoning punk movement, which shared that same rebellious streak. But the message in reggae’s lyrics offered a more lasting form of rebellion — the one-two punch of hope and truth, which ultimately won out over punk’s dead-end nihilism. It’s why reggae’s popularity has grown exponentially in recent decades while punk, frankly, isn’t much more than a glorified footnote (even more so in the U.S.).

The Police evolved from their punk/New Wave beginnings in 1977 to become international superstars in 1983, but reggae definitely played a pivotal role in their repertoire, from hits like “Roxanne” to deeper tracks like “Walking on the Moon” and 1981’s mantra-like “One World (Is Enough For All of Us).” As drummer Stewart Copeland put it, “We plundered reggae mercilessly.”

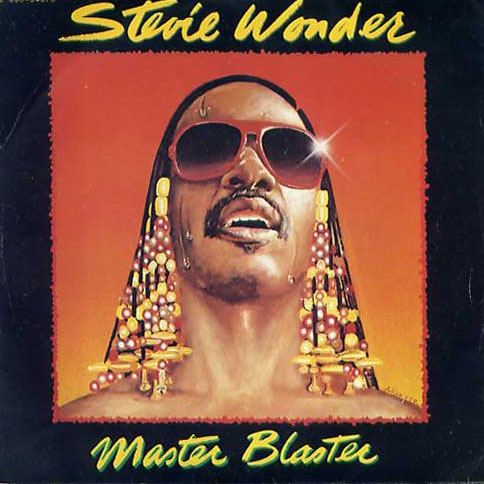

In America, Motown/funk superstar Stevie Wonder was so taken by reggae in general, and Marley in particular, that he wrote a tribute to him in 1980 called “Master Blaster (Jammin’),” which became a #5 hit in the US and #2 in England. Marley and Wonder even performed several shows together that summer.

While many of Marley’s most cherished songs preach love and serenity, his final efforts — 1979’s “Survival” and 1980’s “Uprising” — adopted far more militant tones, as he felt compelled to speak out more against the social injustices he saw on the rise as the ’80s began. Just glance at the changing mood in the song titles: Instead of “One Love” and “Positive Vibration,” we have “Africa Unite,” “So Much Trouble in the World,” “Zimbabwe,” “Ambush in the Night,” “Real Situation,” “Redemption Song.”

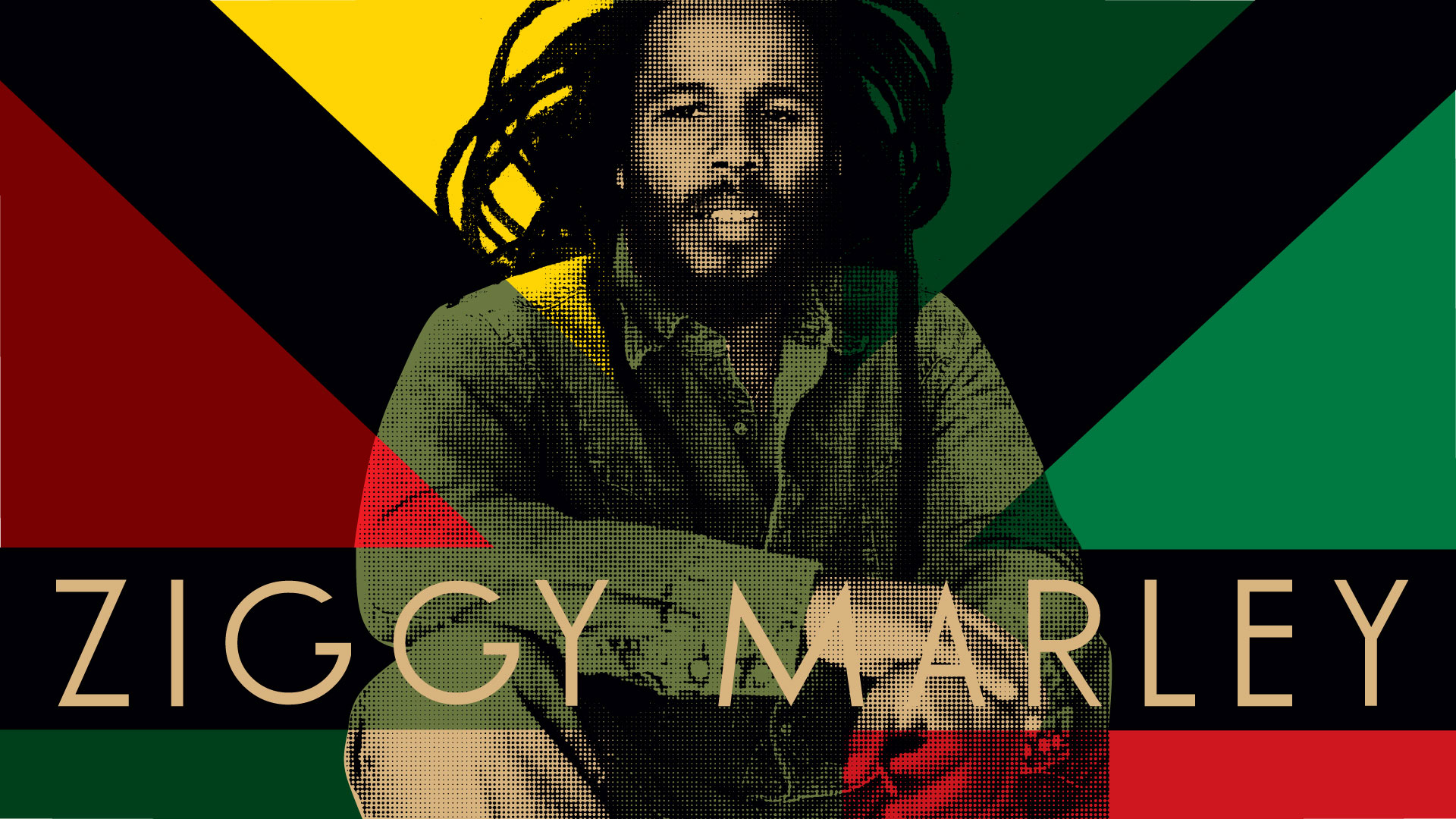

Jamaica was rocked to the core when Marley succumbed to cancer in 1981 at only 36 years old. Four decades later, Marley is still regarded as a figurehead and near-deity among the Jamaican people, and the spread of reggae worldwide is due in large part to his impact. Several of his 11 children have picked up the Marley mantle since then, most notably Ziggy in the late ’80s (particularly “Tomorrow People” in 1988) and Damien in the ’90s, perpetuating and growing the reach and influence of reggae music as their father intended.

In the Eighties, acts like Blondie kept reggae prominently in the picture with their #1 cover version of The Paragon’s “The Tide is High,” and Culture Club contributed reggae-flavored hits like “Do You Really Want to Hurt Me,” which was more an amalgam of multiple styles that included reggae. As Boy George remarked, “In the the ’70s, we had glam rock, but we also had reggae and ska happening at around the same time. I just took all those influences I had as a kid and threw them together, and somehow it worked.”

Some purists regarded these and other non-Jamaican acts like UB40 as “weaker, pastel versions” of true reggae — one critic called it “reggae that wouldn’t frighten white people” — and truth be told, they’re probably right on. And still others never liked reggae to begin with. Morrissey, the iconoclast who served as frontman for The Smiths, one of England’s most popular bands of the ’80s, summarized his feelings this way: “Reggae is vile.”

Me, I enjoy a little reggae now and then, but usually only if I’m sitting by the pool or on the beach. To my ears, it has a certain sameness to it that gets old after a short while. But damn, it’s fun, it’s soothing, it gently gets under your skin, in a good way. Take a listen to the Spotify playlist I’ve assembled below for a healthy cross-section of reggae’s earliest hits and timeless anthems. Or, if you prefer, you certainly can’t go wrong anytime you play Marley’s incredible “Legends” CD compilation, which has now sold more than 30 million copies worldwide.

************************

Britain and Canada eagerly accepted it almost right away, and other European countries and Australia soon followed suit. People in other regions of the world — Central and South America, the Far East, Africa — had very strong allegiances to their own vibrant, indigenous music, so they took a little longer to join the party. Communist governments refused to allow their people to be exposed to free-thinking pop music until well into the 1980s, despite several overt attempts to infiltrate (The Beatles’ 1968 album-opener “Back in the USSR,” for instance).

Britain and Canada eagerly accepted it almost right away, and other European countries and Australia soon followed suit. People in other regions of the world — Central and South America, the Far East, Africa — had very strong allegiances to their own vibrant, indigenous music, so they took a little longer to join the party. Communist governments refused to allow their people to be exposed to free-thinking pop music until well into the 1980s, despite several overt attempts to infiltrate (The Beatles’ 1968 album-opener “Back in the USSR,” for instance). “Leningrad,” Billy Joel, 1989

“Leningrad,” Billy Joel, 1989 “Free Man in Paris,” Joni Mitchell, 1974

“Free Man in Paris,” Joni Mitchell, 1974 “Down to London,” Joe Jackson, 1989

“Down to London,” Joe Jackson, 1989 “Only a Dream in Rio,” James Taylor, 1985

“Only a Dream in Rio,” James Taylor, 1985 “Stranger in Moscow,” Michael Jackson, 1997

“Stranger in Moscow,” Michael Jackson, 1997 “Marrakesh Express,” Crosby Stills and Nash, 1969

“Marrakesh Express,” Crosby Stills and Nash, 1969 “Runnin’ Back to Saskatoon,” The Guess Who, 1972

“Runnin’ Back to Saskatoon,” The Guess Who, 1972 “Still in Saigon,” Charlie Daniels Band, 1981

“Still in Saigon,” Charlie Daniels Band, 1981 “Loco in Acapulco,” The Four Tops, 1988

“Loco in Acapulco,” The Four Tops, 1988 “Woman From Tokyo,” Deep Purple, 1973

“Woman From Tokyo,” Deep Purple, 1973 “Jerusalem,” Emerson, Lake and Palmer, 1973

“Jerusalem,” Emerson, Lake and Palmer, 1973 “Funky Nassau,” Beginning of the End, 1971

“Funky Nassau,” Beginning of the End, 1971 “Fast Boat to Sydney,” Johnny Cash & June Carter, 1967

“Fast Boat to Sydney,” Johnny Cash & June Carter, 1967 “Berlin,” Lou Reed, 1973

“Berlin,” Lou Reed, 1973 “Budapest,” Jethro Tull, 1987

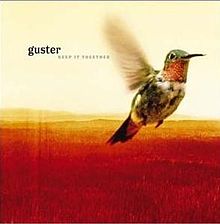

“Budapest,” Jethro Tull, 1987 “Amsterdam,” Guster, 2003

“Amsterdam,” Guster, 2003