I just need some place where I can lay my head

So much of the classic rock music from the 1960s and 1970s is bombastic, frenetic, more show than substance. And then there are the artists who are musical craftsmen, playing their instruments with understated grace and dexterity, and writing honest songs with unique structures and timeless lyrics.

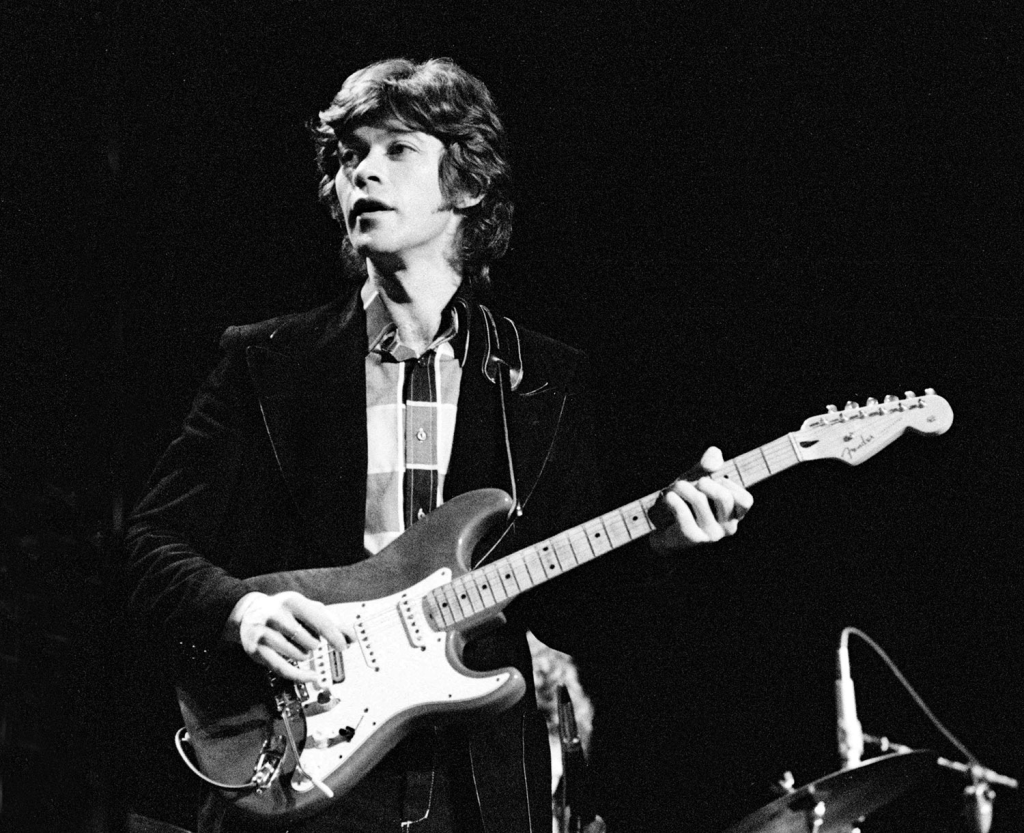

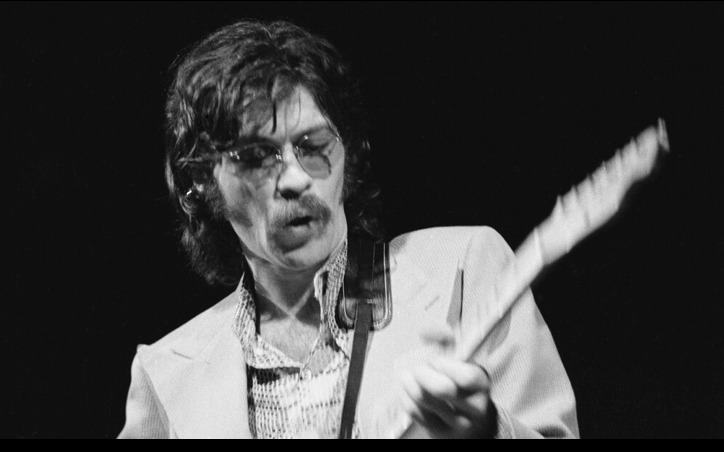

One of the best examples of the latter is The Band and its guitarist/songwriter Robbie Robertson, who died last week at age 80.

Full confession: I have always respected The Band and what they accomplished, but I wouldn’t call myself a big fan. I saw them once in concert (1974) as part of a triple bill and bought only their debut album and a “Best Of” package after they’d disbanded. Once I got around to seeing their acclaimed concert film “The Last Waltz” many years after the fact, I began a comprehensive exploration of their catalog, and am very glad I finally did. There’s much to be enjoyed and admired.

My musician friend Irwin Fisch is what you might call an ardent devotee of The Band, and I sought his knowledge and opinions this past week about their impact on him and on music in general. He responded with so much commentary (both emotional and technical) that I should’ve just turned my blog over to him for this week’s entry. I share some of his observations later on in this tribute.

To call Robertson and his oeuvre influential would be a gross understatement. While The Band enjoyed a period of commercial success, it seems to me that their impact was more broadly felt among other musicians, both their peers and the generations who followed their initial career arc (1968-1976). Consider the comments of these luminaries about the group’s sound and Robertson’s contributions:

“Robbie Robertson is one of my all-time favorite guitar players. He doesn’t need to play 10,000 notes a second. He’s much more concerned with the overall song and structure than his own personal prowess.” — George Harrison, 1970

“R.I.P. Robbie Robertson, a good friend and a genius. The Band’s music shocked the excess out of the Renaissance and was an essential part of the back-to-the-roots trend of the late ‘60s. He was an underrated, brilliant guitar player who added immeasurably to Bob Dylan’s best tour and best album.” — “Miami” Steve Van Zandt

“The way (Robertson’s) guitar was woven into the fabric of those songs helped create some of the greatest timeless music ever made — true American music (from the continent of America) that defies categorization and somehow becomes even more relevant and reverent decade after decade.” — Warren Haynes, The Allman Brothers Band

“For me, it was serious. It was grown-up. It was mature. It told stories and had beautiful harmonies. Beautiful musicianship without any virtuosity. Economy and beauty. Their music shook me to the core. They were craftsmen, and they got it right.” — Eric Clapton, inducting The Band into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994

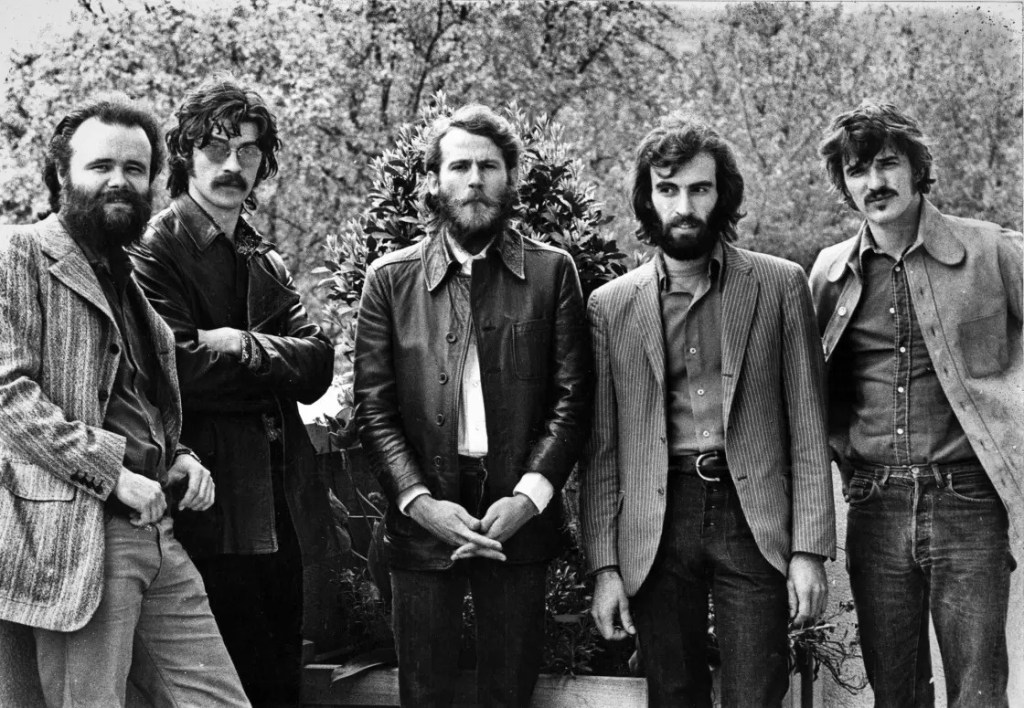

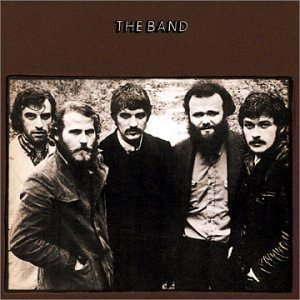

The Band’s body of work — especially its first two LPs, 1968’s “Music From Big Pink” and 1969’s “The Band” — seemed wholly unique, going totally against the grain of both the pop mainstream as well as the psychedelic underground scene of that era. Robertson, drummer Levon Helm, organist Garth Hudson, pianist Richard Manuel and bassist Rick Danko were indeed a band in the best sense of the word: five earnest, dedicated instrumentalists who also sang up a storm and eschewed individual virtuosity in deference to the musical whole. Their recorded legacy stands as a testament to their communal work ethic and their many years as a performing entity honing their craft before they found fame.

*********************

Robertson, born Jamie Royal Robertson in Toronto, was only 18 when he became lead guitarist in The Hawks, a Canadian group that played behind Arkansas rockabilly frontman Ronnie Hawkins in the early ’60s, with drummer (and fellow Arkansan) Helm holding down the beat. Original members fell by the wayside, and were eventually replaced with Hudson, Manuel and Danko, and from then on, the fivesome performed relentlessly behind Hawkins for three long years, even recording a few tracks, like the lively cover of “Who Do You Love?” with Robertson’s scorching lead guitar that got radio play in Canada.

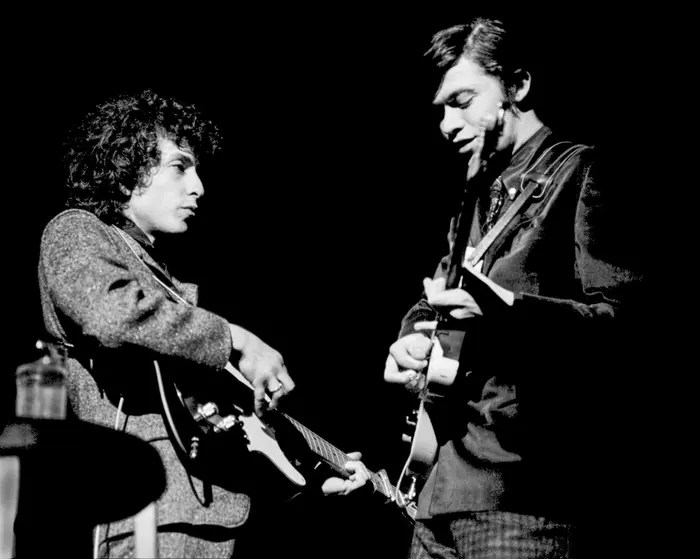

But in 1964, as Helm put it, “We’d always wanted to be our own band, not a backing band for someone else doing blues covers.” They headed out on their own as Levon and The Hawks, developing a sterling reputation as one of the tightest bands in the business. It wasn’t long before Bob Dylan, who was in the midst of a seismic transformation from folkie to rocker, approached Robertson and Helm to play lead guitar and drums at a couple of gigs in New York and L.A. When that led to an invitation to go on a lengthy tour, Helm said, “Hire us all, or don’t hire anybody,” and with that, The Hawks became Dylan’s touring band.

Among Dylan’s original fan base, The Hawks were vilified. “Bob would play his acoustic set, which the folk music crowd loved,” recalled Robertson several years later, “but after intermission when we joined him on stage, the booing started. People didn’t just disapprove. They violently hated it, and I thought, ‘What is this shit about? We’re just playing some music.’ I said to the guys in The Hawks, and to Dylan, ‘They’re wrong. The world is wrong. This is really good.’ We started playing louder, harder, bolder. Kind of preaching our sermon of music. People still said, ‘What’s wrong with these guys? Why do they keep insisting on doing this?’ Somewhere inside, we thought that what we were doing was really good. In time, the world came around.”

Robertson ended up playing on a few tracks from Dylan’s “Blonde on Blonde” LP, notably “Leopard Skin Pillbox Hat,” but after Dylan’s motorcycle accident in 1966 and his self-imposed seclusion, The Hawks chose to hole up in upstate New York near Dylan’s retreat there. They spent many weeks and months writing, rehearsing and recording a broad range of material that, eight years later, would materialize as “The Basement Tapes,” a double album capturing Dylan and The Hawks together.

Meanwhile, the folks at Capitol Records took an interest in The Hawks, who chose to rename themselves simply The Band. Armed with original songs by Robertson, and a couple by Manuel and Dylan, they recorded the unassuming “Music From Big Pink,” a reference to the pink ranch house where they’d been writing and rehearsing. When it was released in July 1968, Robertson reflected, “People said, ‘What is this? This doesn’t fit in. This isn’t what’s happening.’ And we said, ‘Thank you, mission accomplished!'”

Several of the songs (“Caledonia Mission,” “To Kingdom Come,” “Chest Fever”) turned heads, and their version of Dylan’s “I Shall Be Released” may be the best version out there. But the one that truly stood out was “The Weight,” an extraordinary parable with Biblical connotations that established Robertson as a songwriting force to be reckoned with. It remains The Band’s most widely known and beloved piece, a song for the ages.

In addition to their exemplary musicianship, The Band boasted three singers, led usually by Helm, although both Manuel and Danko took turns handling lead vocals on occasion. Their harmonies were not as pristine as, say, Crosby, Stills and Nash, but they offered a rustic nature that perfectly suited the honest lyrics and down-home music. “A little bit of country, blues, gospel and rock, stirred over time into an original stew” is the way one critic described The Band’s sound. It has come to be known as Americana with many followers among more recent generations.

Robertson continued churning out quality material and emerged as the chief tunesmith as they assembled songs for their sophomore effort, 1969’s “The Band,” which is widely regarded as the group’s high-water mark. It was a critical success and reached #9 on the US album chart, spurred by the single “Up on Cripple Creek” (which reached #25) and such gems as “The Unfaithful Servant,” “King Harvest (Has Surely Come)” and “Across the Great Divide.” Also found on the album was “The Night They Drove Old Dixie Down,” the classic tale inspired by the final days of the Civil War which, unfortunately, is better known by the inferior cover version Joan Baez recorded in 1971.

Their next album, “Stage Fright,” charted even higher (#5), but 1971’s “Cahoots” was flat and uninspired, giving lie to reports that all was not well in The Band’s camp, where excessive drug and alcohol use were taking their toll on the music and relationships among the members. In Robertson’s memoir “Testimony,” he wrote how Danko and Helm in particular developed a heroin habit while Manuel fell prey to alcohol abuse. Robertson admitted he, too, experimented but not to the extent of some of the other members. “Being in the moment at the time, it was, on a good day, frightening to think, ‘I hope somebody doesn’t die.’ Let me be very clear: I was no angel. I was not Mr. Responsible. I was just better off than others, and in a position to say, ‘Is everyone okay?'” In addition to the songwriting, he also took on a more active role in their financial matters.

It should be mentioned that Helm held a simmering resentment against Robertson for failing to give him (and Manuel and Danko) partial songwriting credit on songs they helped compose. In particular, Helm claims he wrote lyrics passages in “The Weight” but never saw any royalties, and he complained publicly about it in his 1994 autobiography “This Wheel’s on Fire.” The Helm/Robertson estrangement went on for decades and kept Helm away from the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony.

In any event, in 1972, a strong double live LP, “Rock of Ages,” masked the internal problems for a spell, but a limp album of covers that followed, 1973’s “Moondog Matinee,” had people worriedly shaking their heads. What had become of these former musical heroes?

The Band reunited with Dylan for his “Planet Waves” LP and returned to the concert circuit with him for an enormously successful tour, captured on the double live LP “Before the Flood,” which peaked at #3 in 1974. But Robertson, showing signs of disillusionment at the grueling life on the road, relocated to Malibu, California, in 1975. There, he wrote the batch of songs which would become, in essence, the original lineup’s final studio album, “Northern Lights – Southern Cross,”” which includes such fine moments as “Ophelia,” “It Makes No Difference,” “Forbidden Fruit” and a personal favorite, “Acadian Driftwood.” Critics were mixed about it, some calling the production “glossy and slick” with little of the close-knit playing that marked their earlier achievements, but I like it just fine.

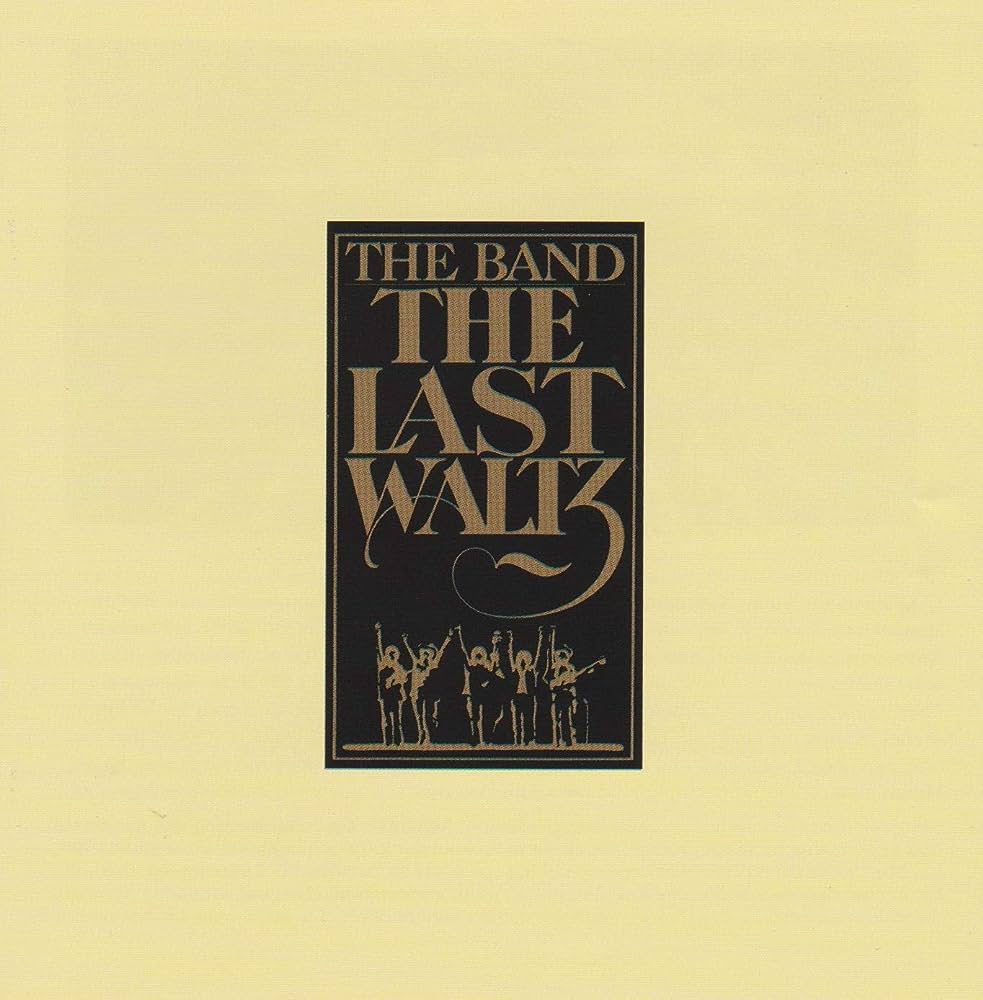

Robertson orchestrated the disbanding of the group with an extravagant, all-star Thanksgiving 1976 concert at San Francisco’s Winterland labeled “The Last Waltz.” No doubt sensing this would be viewed as “going out on top,” all five members turned in superb performances, as did such guests as Joni Mitchell and Van Morrison. Robertson sought out filmmaker Martin Scorsese, whose career was in a valley of sorts between the peaks of “Taxi Driver” and “Raging Bull,” and he agreed to film the event, ultimately adding documentary-type interview footage, redefining how good a rock concert film could be when it was released to rave reviews in 1978.

Robertson and Scorsese nurtured a mutual admiration over the ensuing decades as they collaborated on numerous projects, including the successful “Casino” and “The Wolf of Wall Street” and, most recently, “Killers of the Flower Moon,” due to be released later this year. Robertson also did some film producing, screenwriting and acting, most notably in 1980’s “Carny,” inspired by his time working with carnival people in his youth.

Robertson never completely gave up on traditional songwriting and recording, eventually releasing six solo studio LPs of original material between 1987 and 2019. His eponymous debut, produced by wunderkind Daniel Lanois and featuring Peter Gabriel, includes such stellar tracks as “Fallen Angel” (a tribute to Manuel, who had taken his own life the previous year) and the spooky “Somewhere Down the Crazy River.” Of the other five solo albums, I’m partial to his 2011 package titled “How To Become Clairvoyant,” featuring a slew of guests like Eric Clapton, Tom Morello, Steve Winwood and Trent Reznor.

So what was it about Robertson that made him so special? Let’s turn it over to Irwin:

“He seemed to be unusually well read, and everybody talks about how his songs vividly conjure the American South of old, or at least its archetypes and mythology. His imagery was cinematic and specific, exemplifying the “show it, don’t tell it” maxim of great writing. He very rarely used adjectives. His verses were like closeups, focusing solely on characters, their words and their actions, while his choruses were more like wide shots, suspending the narrative to comment on it (often obliquely) and give the bigger picture.”

“Musically, you can hear that he’d absorbed a lot of rock ’n’ roll, country, folk and gospel, but he melded them into his own language. Robbie’s songs were the perfect grist that put and kept The Band’s mill in business. As unique, phenomenally crafted and captivating as the songs were, it’s hard to imagine how they’d be regarded without the voices of Levon, Richard and Rick, and the arrangements and playing of The Band as a well-oiled unit.

“To me, Robertson’s guitar playing was unmistakable in its phrasing, especially on his solos. It was a conversational style, taken from the blues. His solos were raw, unstructured monologues, never composed, never a climatic ending. He finished what he had to say and stopped talking.”

There you have it. Gifted lyricist, inventive songwriter, distinctive guitarist. An enormously influential presence during his time among us, and now he’s gone. But his recorded legacy remains, and Irwin and I urge you to dive into the bounty he left behind.

*********************