All I have to hold on to is a simple song at last

“His songs weren’t just about fighting injustice; they were about transforming the self to transform the world. He dared to be simple in the most complex ways — using childlike joy, wordless cries, and nursery rhyme cadences to express adult truths. His work looked straight at the brightest and darkest parts of life and demanded we do the same. As I reflect on his legacy, I’m haunted by the eternal cry of ‘Everyday People’: ‘We got to live together!’ Once idealistic, now I hear it as a command.” — Questlove

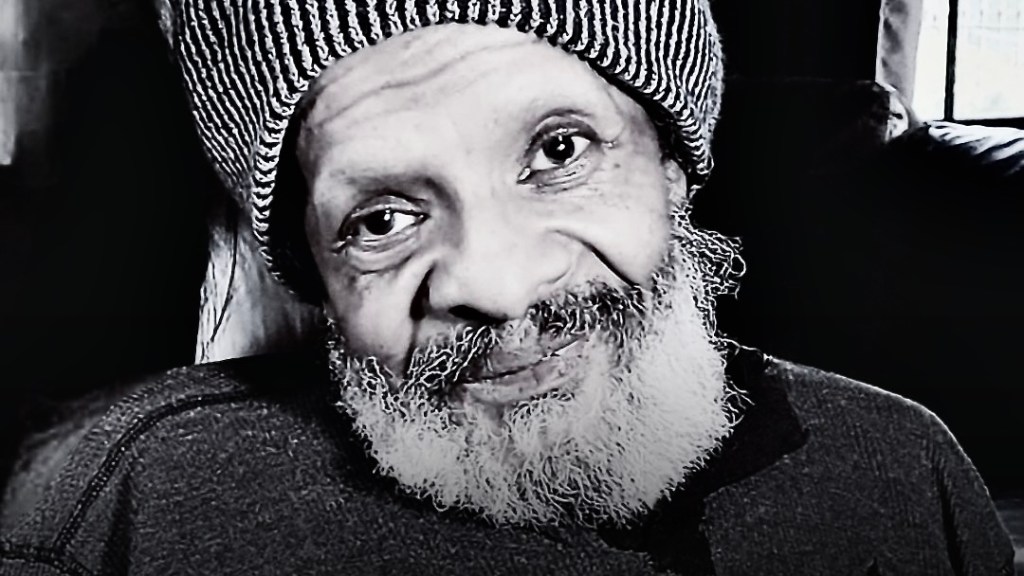

Sylvester Stewart, known worldwide as Sly Stone, died this week at age 82, and the subsequent outpouring of love and respect for the man and his musical accomplishments makes clear how widespread his influence was, and still is.

There’s no denying the excessive and self-indulgent drug use that curtailed his career and turned him into a recluse for most of the past 40 years. Here at Hack’s Back Pages, though, I prefer to focus on his extraordinary musical innovations that wiped clean and redrew the boundaries between rock, soul, funk and pop in the late ’60s and early ’70s, setting the stage for many other artists to do the same in more recent times.

The songs and albums released by Sly and The Family Stone between 1967 and 1973 were wonderfully diverse and mesmerizing. As veteran Rolling Stone editor Ben Fong-Torres put it back in 1970: “Sly and the Family Stone became the poster children for a particularly San Francisco sensibility of the late Sixties: integrated, progressive, indomitably idealistic. Their music, a combustible mix of psychedelic rock, funky soul and sunshine pop, placed them at a nexus of convergent cultural movements, and in turn, they collected a string of chart-topping hits.”

I was about 12 when I first heard the irresistible soul groove of “Dance to the Music,” with lyrics that gave us all a tutorial on how a great dance tune is created: “All we need is a drummer, for people who only need a beat… /I’m gonna add a little guitar and make it easy to move your feet… /I’m gonna add some bottom so that the dancers just won’t hide… /You might like to hear my organ, I said ‘Ride Sally Ride’… /You might like to hear the horns blowin’, Cynthia on the throne, yeah!…”

Shortly after that, I was among the millions who were inspired by the sublime pop and inclusive lyrical message of “Everyday People,” Sly’s first of four #1 hits. Deftly using the children’s teasing “na na na na boo boo” melody, Stone wrote a timeless song of universal optimism and harmony, with words protesting prejudice that were so relevant in 1968 and are even more so today: “There is a long hair that doesn’t like the short hair for being such a rich one that will not help the poor one, /Different strokes for different folks… /We got to live together!…”

A third big hit in the summer of ’69, “Hot Fun in the Summertime,” continued Stone’s penchant for coming up with upbeat soul, augmented by blissful vocal and instrumental flourishes. The song came out just before the band’s game-changing appearance at Woodstock in August, which greatly enhanced their reception by the hippie crowd. That response grew exponentially when the film and album of the festival came out in 1970, highlighted by the performance of “I Want to Take You Higher,” cementing Sly and The Family Stone as superstars of the period.

Perhaps the high-water mark came at the dawn of the Seventies with the release of “Thank You (Falettinme Be Mice Elf Agin)” a hugely impactful song that placed Sly and his group squarely at the forefront of the burgeoning funk movement. As one critic put it, “James Brown may have invented funk, but Sly Stone perfected it.”

Where did all this innovation come from? Sylvester Stewart was born in 1943 in Dallas as part of a large family with Pentecostal/gospel roots, a family who encouraged a broad range of musical expression. Once the family relocated to the Bay Area in California, Stewart and his younger siblings formed a vocal group, The Stewart Four, and cut a gospel record, “On the Battlefield of the Lord,” which received modest targeted airplay. Sylvester and his brother Freddie also both did stints in student bands in high school and beyond.

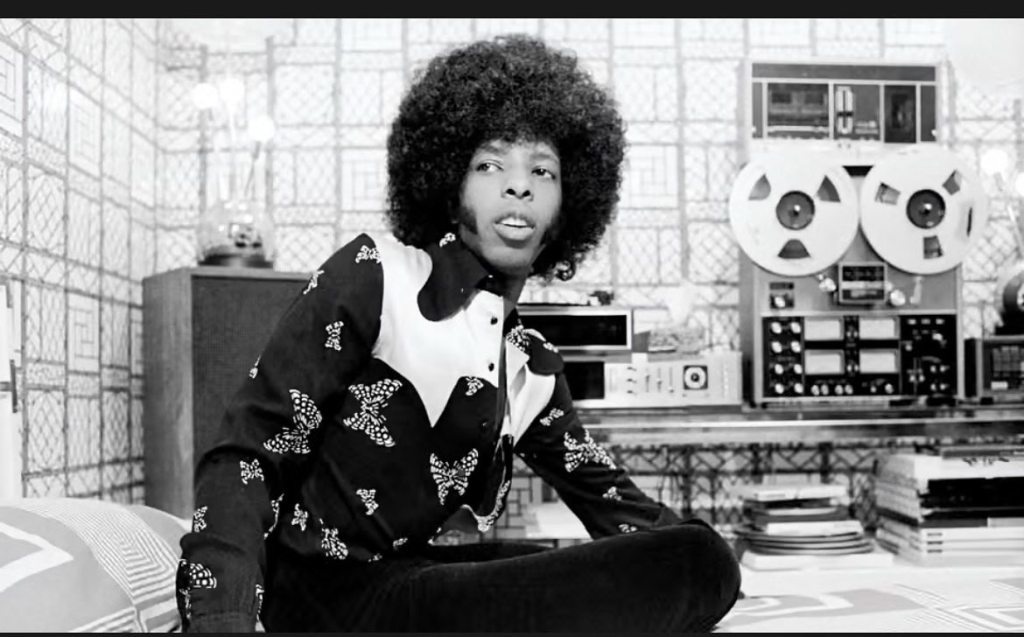

By the time he was 21, Sylvester had adopted the name Sly Stone as a disc jockey in San Francisco, playing a diverse playlist of white and black artists doing rock, soul, jazz and gospel. “In radio,” Stone said, “I found out about a lot of things I don’t like. Like, I think there shoudn’t be ‘Black radio.’ Just radio. Everybody be a part of everything.” He resisted narrow radio formats and instead thrived on a blend of musical styles, from The Beatles and The Rolling Stones to Jan and Dean and The Righteous Brothers to Marvin Gaye and Dionne Warwick. He also worked for a local label as a producer, writing and producing Bobby Freeman’s #5 hit “C’mon and Swim” in 1964 and working with Grace Slick’s first band, The Great Society.

In 1966, Stone and his brother were both gigging with their own bands and decided to merge the best players in each group to create one integrated “family” comprised of men, women, blacks and whites: Freddie (Stewart) Stone on guitar, Larry Graham on bass, Cynthia Robinson on trumpet, Gregg Errico on drums, Jerry Martini on sax and Sly Stone on keyboards. Rose (Stewart) Stone joined the lineup in 1968. And everyone sang.

Sly and The Family Stone’s first LP, aptly named “A Whole New Thing,” won critical praise but sold poorly, and their next two albums didn’t do much better, but the aforementioned singles “Dance to the Music” and “Everyday People” put them on the map. Sly was at the helm producing, writing and singing as the group assembled their remarkable 1969 LP “Stand!”, which was peppered with accessible hits (“Sing a Simple Song,” “You Can Make It You Try,” “Somebody’s Watching You”) juxtaposed with bolder tracks like the funk jam “Sex Machine” and the incendiary “Don’t Call Me Nigger, Whitey.”

As the group’s fame took off in 1969-1970, sadly, so did Sly’s affection for cocaine, which often made him unpredictable and unreliable. His (and consequently the band’s) reputation suffered as the drug use made him chronically late for many concerts, if he showed up at all. He surrounded himself with a sketchy entourage of handlers and bodyguards, and retreated much of the time into isolation and paranoia.

He later said the pressures of being an innovator, bandleader and role model became too intense. He found himself influenced by the angry rhetoric of the Black Panthers, who urged (some say demanded) that he replace the two white members of the band with black musicians, and write songs that more accurately reflected their militant views. In the spring of 1971, Marvin Gaye released his landmark LP “What’s Going On?”, and Stone seemed to respond to that question with “There’s a Riot Goin’ On,” an album that saw Stone doing an about-face from sunny optimism to darker pessimism.

He recorded most of it on his own, some of it alone in his Bel Air loft, overdubbing relentlessly with emphasis on the then-new drum machine technology, and an overall murky sound dominated by electric piano (played by guest Billy Preston) instead of guitar. The lyrics took on a more strident tone that reflected racial unrest in songs like “Luv n’ Haight,” “Running’ Away” and “Thank You For Talkin’ To Me Africa.” Reaction to this departure was mixed; one reviewer called the album “a challenging listen, at times rambling, incoherent, dissonant, and just plain uncomfortable.” Still, it managed to reach #1 on US album charts, as did its somber single “Family Affair” (although its lyrics focused not on the joy of family but on the dysfunctional family).

Perhaps sensing that he’d let the pendulum swing too far, Stone re-emerged in 1973 with the decidedly more commercial album “Fresh,” which turned out to be the group’s last Top Ten album, and its hit, “If You Want Me to Stay,” their final Top Twenty appearance. It comes across as upbeat as “Riot” was hostile, and included not only his most overt love song, “Let Me Have It All,” but also the only cover Sly ever recorded, and a curious choice it was: “Que Sera Sera,” the old Doris Day hit, radically reworked with Rose Stone on vocals. There’s actually a song called “If You Want Me to Stay” that warned us all we shouldn’t expect much from him going forward: “You can’t take me for granted and smile, /Count the days I’m gone, forget reachin’ me by phone /Because I promise I’ll be gone for a while…”

In 1974, Stone took the unusual step of getting married on stage at a Madison Square Garden concert, but that spectacle of a wedding became a marriage that crashed and burned in a matter of months. Sly and The Family Stone also dissolved as a band around that time, and Stone’s career seemed to fall precipitously, despite several lame comeback attempts. His 1976 effort, “Heard You Missed Me, Well I’m Back,” didn’t even chart, and his label released him. In 1979, the folks at Epic chose to release “Ten Years Too Soon,” a poorly conceived disco remix of a handful of his best work of the late ’60s. (It’s mercifully out of print, but I found the discoed version of “Everyday People” on Spotify and included it on my playlist so you can judge for yourself.)

One last release, 1982’s “Ain’t But the One Way,” was supposed to be a collaboration between Stone and Funkadelic’s George Clinton, but both men seemed to give up on it, and it sounds like it. One reviewer wrote, “When a once politically astute pop statesman writes an ode to New Jersey called ‘Hobo Ken,’ you know something is wrong. If you crave the beat, you’ll find it here, but in no way can this album be regarded as a success.”

Stone retreated further and further from public life. He was arrested for cocaine possession multiple times in the 1980s, and he served 14 months in a rehab center beginning in 1989. He made a few unimpressive talk show appearances, and he showed up at Sly and The Family Stone’s 1993 induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame, and at the 2006 Grammy Awards for a group tribute, but otherwise, he seemed to have vanished. He claimed in 2007 that he had “a library of about a hundred new songs,” but they never saw the light of day except for three new tracks on “I’m Back! Family and Friends,” a lackluster 2011 re-recording of ’60s songs with selected guests (Jeff Beck, Ray Manzarek, Ann Wilson) making instrumental contributions. It, too, failed to chart.

Despite all these setbacks, Sly Stone’s legacy as a pioneer and innovator remains steadfast among many dozens of musicians who emulated his music and raved about his impact on their own records. Jazz greats Miles Davis and Herbie Hancock began incorporating electric instruments and funk grooves into jazz, while Prince, Red Hot Chili Peppers and The Roots have all covered Sly & the Family Stone songs.

Questlove, leader of The Roots and a dedicated rock/funk historian, is behind the recently released documentary, “Sly Lives! (a.k.a. The Burden of Black Genius),” which deftly tells Sly’s story, warts and all. “Yes, Sly battled addiction,” he said. “Yes, he disappeared from the spotlight. But he lived long enough to outlast many of his disciples, to feel the ripples of his genius return through hip-hop samples, documentaries, and his memoir (published in 2023). Still, none of that replaces the raw beauty of his original work.”

Emilio Castillo, bandleader for Tower of Power, added, “All of us in music today owe a great deal to his influence on our music. He greatly influenced the way I approach rhythm, and also the way we in Tower of Power approach live performance. I pray that I will see him up there in heaven and I know that the band up there, with Otis and Jimi and all other greats, just got a whole lot better.”

Even some of his abandoned Family Stone members had kind words in the wake of his death. “I feel like a piece of my heart left with Sly,” said sax man Jerry Martini. “We were close friends for 60 years. He credits me with starting the band, but it was his musical genius that made music history. He will always be in my heart, and I will continue to celebrate his music with the Family Stone. Rest well, my dear friend. You will be greatly missed.”

Marvin Gaye’s daughter Nona weighed in with this comment: “He was family to our family. My father had deep respect for him, and I carry that same love and admiration. Thank you, Sly, for breaking boundaries, for making noise that mattered, and for never playing it safe. Your courage in sound will never be forgotten. Fly high, beautiful soul. The funk is eternal now.”

R.I.P., Sly.

***************************

This Spotify playlist offers about 30 tracks by Sly and The Family Stone — hits as well as deeper album tracks — arranged chronologically according to release date.