All a friend can say is ‘ain’t it a shame’

“I’ll say this: I look forward to dying. I tend to think of death as the last and best reward for a life well-lived. That’s it. But I’ve still got a lot on my plate, and I won’t be ready to go for a while.”

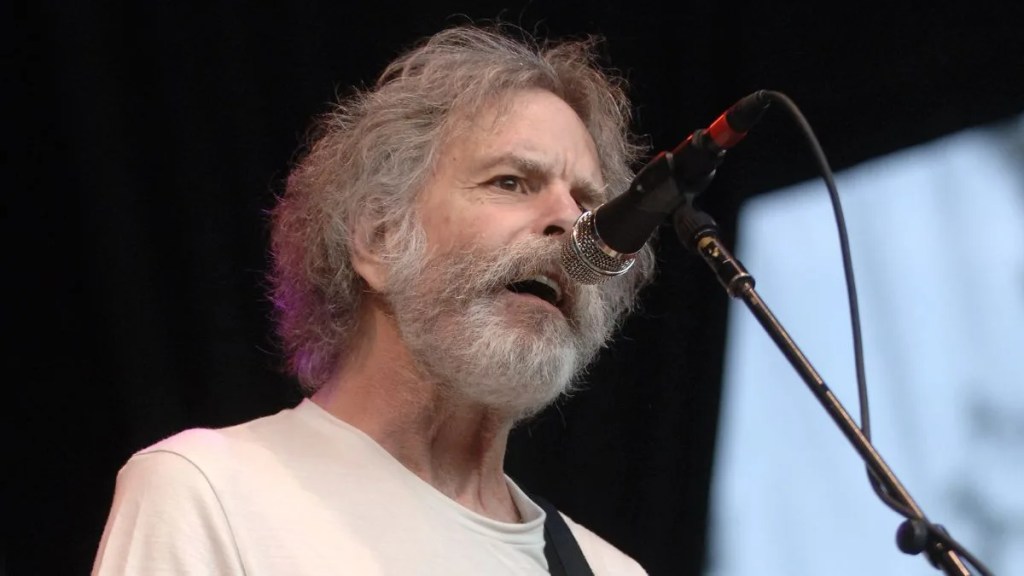

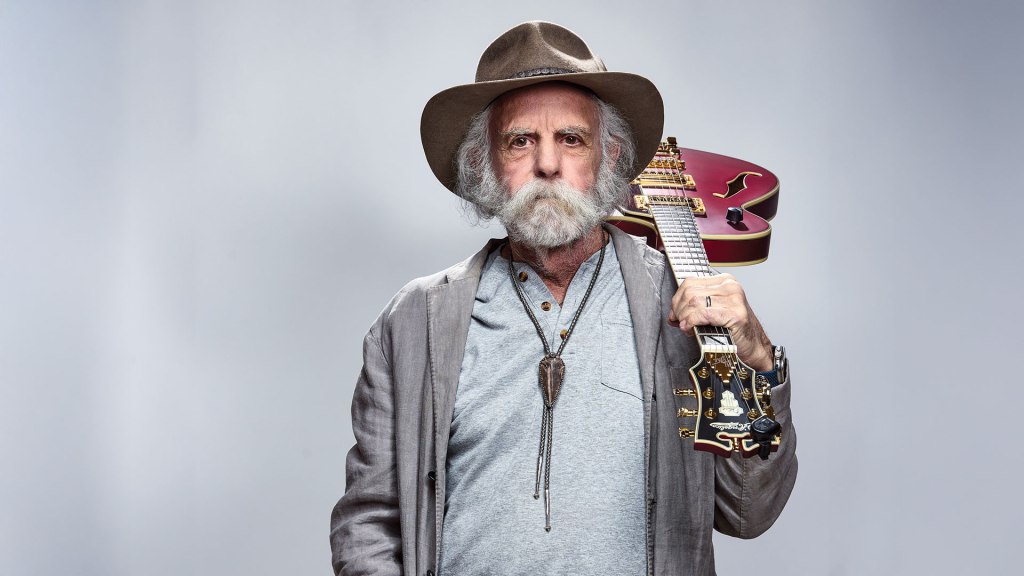

Those were the words of Bob Weir, founding member of The Grateful Dead, in a March 2025 Rolling Stone interview. Sadly, though, the end came sooner than he planned. He died this week at age 78, of lung-related issues following a battle with cancer.

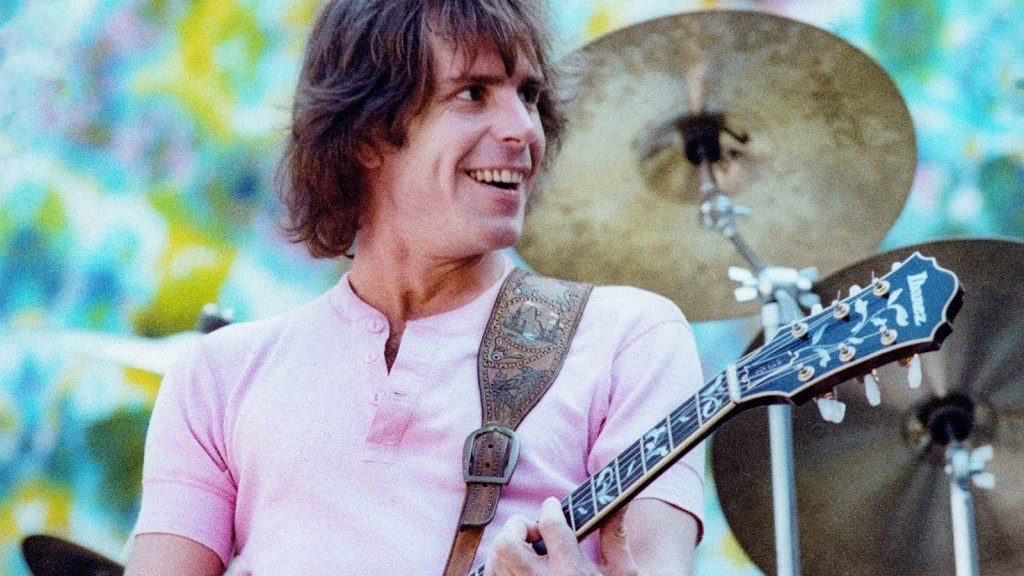

Widely respected as a guitarist, singer, songwriter and humanitarian, Weir had been a relentless musical force for more than 60 years, mostly as the unique rhythm guitarist and occasional lead vocalist of The Grateful Dead from its inception in 1965 until its dissolution in 1995. Since then, he remained a vibrant presence in several spinoff ensembles, most recently on tours with Dead & Company since 2015.

“Heaven’s choir just gained a beautiful new voice,” said guitarist Billy Strings, who has performed in support of and alongside Weir in Dead & Company. “There is joy in knowing he is with some of his old friends again, singing and laughing and playing beautiful songs.”

He added, “Bob was always ready to ‘kick up a fuss,’ as he put it. He always had boundless time and knowledge to share with everyone, and he was truly one of the kindest people I’ve ever known. I’m extremely grateful to have crossed paths with him in this life.”

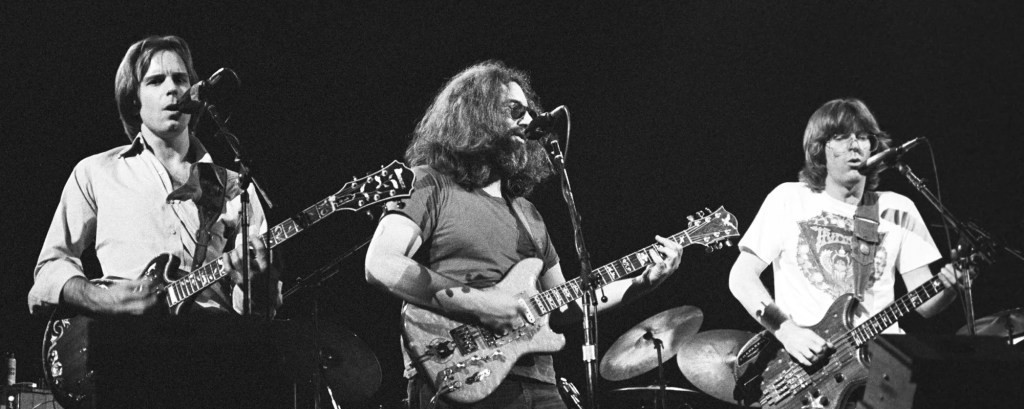

As far as I’m concerned, Weir was as indispensable to The Grateful Dead as lead guitarist Jerry Garcia, who was the group’s spiritual leader and chief singer/songwriter. To my ears, Weir was the better singer, and he wrote or co-wrote some of The Dead’s most enduring songs: “Truckin’,” “Sugar Magnolia,” “One More Saturday Night,” “Playing in the Band” and “Estimated Prophet,” to name just a few.

According to a New York Times obituary by Ben Sisario, “Weir strummed his rhythm chords lightly, nimbly and malleably, charting and shaping the ever-shifting undercurrents of The Dead’s songs and jams. Bluegrass, blues, country, funk, reggae, mariachi and jazz were all at his fingertips. He was a consummate ensemble player — a full participant in the improvisatory mix who was somehow able to almost vanish into the background while he made the other players shine.”

But he was also a charismatic, good-looking guy who stood front and center on stage as the visual focal point between Garcia and bassist Phil Lesh. “It was Beautiful Bobby and the ugly brothers,” chuckled John Barlow, Weir’s lyricist/collaborator. “The women flocked to him.”

While I admired The Dead’s musical chops and what they were able to achieve in their three decades in the business, I would say I’ve been no more than a modest fan of the band over the years. I own the two marvelous LPs from 1970, “Workingman’s Dead” and “American Beauty”; the awesome triple live album, “Europe ’72”; and their surprising commercial comeback in 1987, “In the Dark.” But if I were to list my favorite rock artists, The Dead probably wouldn’t make my Top 30.

Part of the reason, I think, is that I never felt like I was a part of the one-of-a-kind bond the band shared with its core audience. I felt like an outsider, even though I was sympathetic to the sweet devotion, sharing and general kindness that were the hallmarks of the relationship between the band and its fans, lovingly referred to as Deadheads. I feel as if I missed that era.

Funny thing, though — I’ve immersed myself in The Dead’s catalog over the past several days and have discovered a number of choice studio tracks (“Alabama Getaway,” “Scarlet Begonias,” “Picasso Moon”) and live jams that have made me reconsider where I rank them in the classic rock pantheon.

It’s a nearly impossible task, by the way, to try to familiarize yourself with The Dead’s recorded output. You can absorb their 13 studio LPs, and even their nine live albums released during their heyday, but there are also upwards of 250 (!) live concert recordings, which first surfaced as bootlegs but were eventually released officially between 1991 and 2011.

***********************

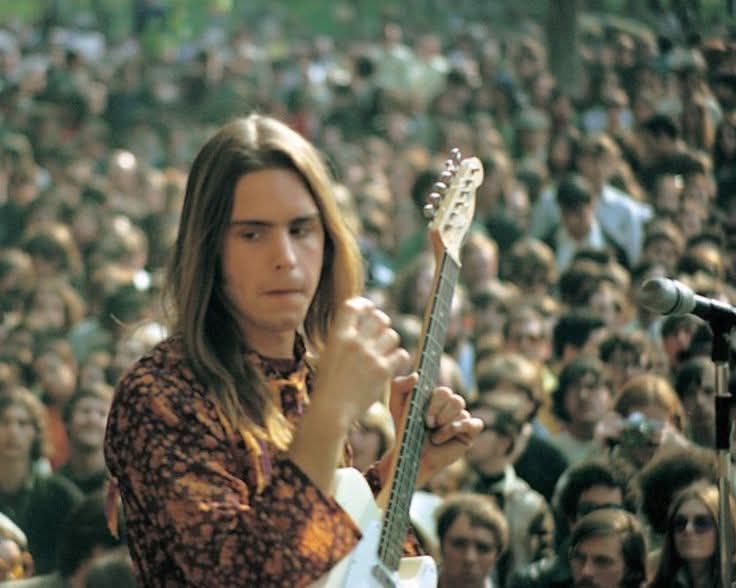

Weir was a good natured kid but rebellious, raised by adoptive parents in the San Francisco Bay Area. He picked up the guitar at 13 and dropped out of school at 16 around the time he met 21-year-old Garcia, who was playing banjo in a jug band. Weir became “The Kid,” the youngest member of The Warlocks, consisting of Garcia, Lesh, organist-vocalist-harmonica player Ron “Pigpen” McKernan and drummer Bill Kreutzmann. Before his 18th birthday, Weir moved into the group’s communal house in the Haight-Ashbury district in 1966.

As the story goes, the name “Grateful Dead” happened serendipitously when Garcia opened a big book and saw the two words positioned opposite each other on facing pages. It turned out the phrase also had a deeper meaning: It refers to folk tales in which “a dead person, or his angel, shows gratitude to someone who, as an act of charity, arranged for their proper burial.” They found this act of kindness in keeping with their overarching spirit of community. Stumbling on that phrase in a book was just the sort of cosmic randomness that fascinated the group, and it came to dominate how the band would exist throughout its lifetime. “Every night that we went out on stage, you never knew what might happen,” said Lesh. “We rarely had a prepared set list. We just played what felt right at that moment. I just loved that about us.”

At first, Weir had to pay some dues. He admitted that too much LSD during the group’s stint as house band for the infamous Ken Kesey Acid Tests made him withdrawn, especially as Garcia and Lesh were uniting more musically. “At the beginning, I was definitely low man on the totem pole,” he told Rolling Stone in 1989, “and for a long time I had to just shut up and take it.” Indeed, he was actually dismissed from the group for not taking his musical development seriously, which lit a fire under him and precipitated his return to the fold in time to be involved in their debut LP in 1967.

By 1970, Weir came into his own as a singer-songwriter when “Truckin'” became a hit single in certain markets (although only #63 on national pop charts). That song and his sublime “Sugar Magnolia” evolved into long jam versions at nearly every concert, with Weir providing ever more sophisticated rhythm guitar parts to complement Garcia’s solos and Lesh’s countermelodies.

Later, in a 1978 interview, Weir explained how he saw his role in the group. “I try to provide counterpoint for what Jerry does. He was lead, and I was rhythm. Those were our defined roles. I was there to play rhythm and chords for Jerry to play over the top of, but the traditional role of a rock and roll rhythm guitarist is somewhat limited. I was feeling a bit hemmed in. At the time, I was listening to a lot of jazz, the piano players like McCoy Tyner and how he chorded underneath John Coltrane, supplying all kinds of harmonic counterpoint to what he was doing on sax. That appealed to me greatly, and I started trying to learn to do that on guitar for Jerry.”

Garcia concurred, adding, “Weir is an extraordinarily original player, in a world full of people who sound like each other. I don’t know anyone else who played guitar the way he does. That was a big score for us, considering how derivative almost all electric guitar playing is.”

To my ears, one of the best examples of stellar ensemble playing by Weir, Garcia and Lesh is on the live version of “Truckin'” from the “Europe ’72” live package. The lead and rhythm guitar interweaving with the bass underpinning is just magnificent. It’s on my Spotify playlist below. Slip in some ear buds and crank it up, paying special attention to what Weir is doing. Serious musical architecture going on there.

Said Talking Heads guitarist Jerry Harrison in 2014, “An awful lot of attention went to Jerry, but to me, it was more really the interplay between Bob and the band that I found the most exciting thing about The Grateful Dead.”

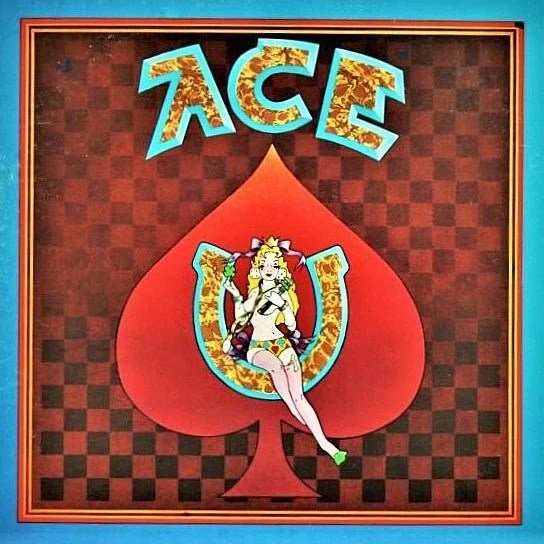

Even more impressive to some was Weir’s debut solo LP “Ace,” released in 1972, demonstrating more clearly that he was a songwriter and singer to be reckoned with, and the rest of the group knew it. Nearly every track — especially “Playing in the Band,” “Cassidy” and “One More Saturday Night” — became staples of The Dead’s concert setlist.

Weir enjoyed the simplicity of country music and cowboy narratives (which showed up most prominently on his rustic 2016 solo LP “Blue Mountain”), but his songwriting explored well beyond the three-chord basics. He experimented with unusual time signatures and tempos, and in his challenging 13-minute piece “Weather Report Suite,” he leaned into old-world lute music and even gospel.

He was as surprised as anybody when The Grateful Dead, always an “album band” and an “in-concert band” more than a “singles band,” found themselves with a Top Ten hit in 1987 when Garcia’s good-natured “Touch of Grey” reached #9 on US pop charts with lyrics that captured their position as rock survivors: “Oh, well, a touch of grey kind of suits you anyway, /That was all I had to say, but it’s alright, /I will get by, I will survive, /We will get by, we will survive…”

From that same “In the Dark” LP, Weir gave us “Hell in a Bucket,” a rollicking rocker that offers one of the quintessential lines about the rock and roll lifestyle he and others led: “I may be going to hell in a bucket, babe, but at least I’m enjoying the ride.”

When asked about the fierce devotion of The Deadheads over the years, Weir looked at it this way: “We started to realize our fans were a little bit different when we started seeing the same faces in the front row every night on a tour. It came home a little more when we saw tents set up in the parking lot. ‘Okay, we have a little gypsy entourage going here.’ It was a following of people who had, perhaps temporarily, dropped out of normal society and just followed us around, creating their own little society. That’s kind of what I had done, dropped out, ran off with a rock and roll band, chasing the muse, chasing the music.”

Those who worked with him said Weir always seemed to be inquisitive, seeking new ways to communicate through music. Indeed, in a 2019 interview, Weir noted, “I’ve always known a song was a critter. A new one comes through the door, and I want to check it out. I want to sniff its butt, and I want it to sniff mine. You know, Jerry came to me in a dream not long ago and introduced a song to me. It was kind of protoplasmic – you could see right through it – but it was like a great big sheepdog. And he just confirmed to me what I always suspected: that a song is a living organism.”

He was obsessed with making and performing music in multiple forms and formats. Even when The Dead were on hiatus, Weir formed other collaborative projects with seasoned musicians. In bands like Bobby & The Midnites, Weir joined forces, however temporarily, with jazz greats Billy Cobham and Alphonso Johnson. These efforts didn’t always pay off, but Weir kept trying, kept playing, kept singing. After The Grateful Dead’s denouement in 1995, he was the catalyst behind ensembles like RatDog, Wolf Bros., The Dead, and Dead & Company, with people like bassist/producer Don Was, Rob Wasserman and younger superstars like John Mayer.

“Night after night, in the seven years I played with Bobby in the Wolf Bros.,” said Was, “he taught us how to approach music with fearlessness and unbridled soul, pushing us beyond what we thought was musically possible. Every show was a transcendent adventure into the unknown. Every note he played and every word he sang was designed to bring comfort and joy to our audiences. The music he helped create over the last 60 years will continue to be felt for generations. As he sang in one of my favorite Dead songs, ‘The music will never stop.'”

Mayer, who called Weir “my cosmic mentor and an absolute savant,” spoke directly to him in the wake of his death. “Bobby, thanks for letting me ride alongside you. It sure was a pleasure. If you say it’s not the end, then I’ll believe you. I’ll meet you in the music. Come find me anytime.”

Kreutzmann, who may have spent more time on stage and off stage with Weir than just about anybody, spoke at length about his bandmate this week. Among his comments:

“We embarked on a journey without a destination. We didn’t set out to change the world, or to become big stars, or to have our own counterculture — we didn’t know any of those things were actually possible.”

“Nothing was more important than having fun, and nothing was more fun than playing music, especially once audiences started coming and we could look out and see a sea of people dancing. Once that happened, it was all we wanted to do. We didn’t want to stop. That was our first real goal — to just keep going. And so, for sixty years, the music never stopped. This was true for all of us, together and apart, but when Bob was off the road, all he wanted to do was get back on it.”

“I just hope he was able to bring his guitar with him, or otherwise, he’ll go crazy.”

Weir’s grown daughter Chloe served as family spokesperson in a statement. “Bob Weir will forever be a guiding force whose unique artistry reshaped American music. There is no final curtain here, not really — only the sense of someone setting off again. May we honor him not only in sorrow, but in how bravely we continue with open hearts, steady steps, and the music leading us home. As he liked to say, ‘Hang it up and see what tomorrow brings.'”

*******************

For those curious to learn more about Weir’s life and career, Netflix is currently streaming “The Other One: The Long Strange Trip of Bob Weir,” a fascinating 2015 documentary in which Weir offers a feast of observations about life, love and music. I strongly recommend it.

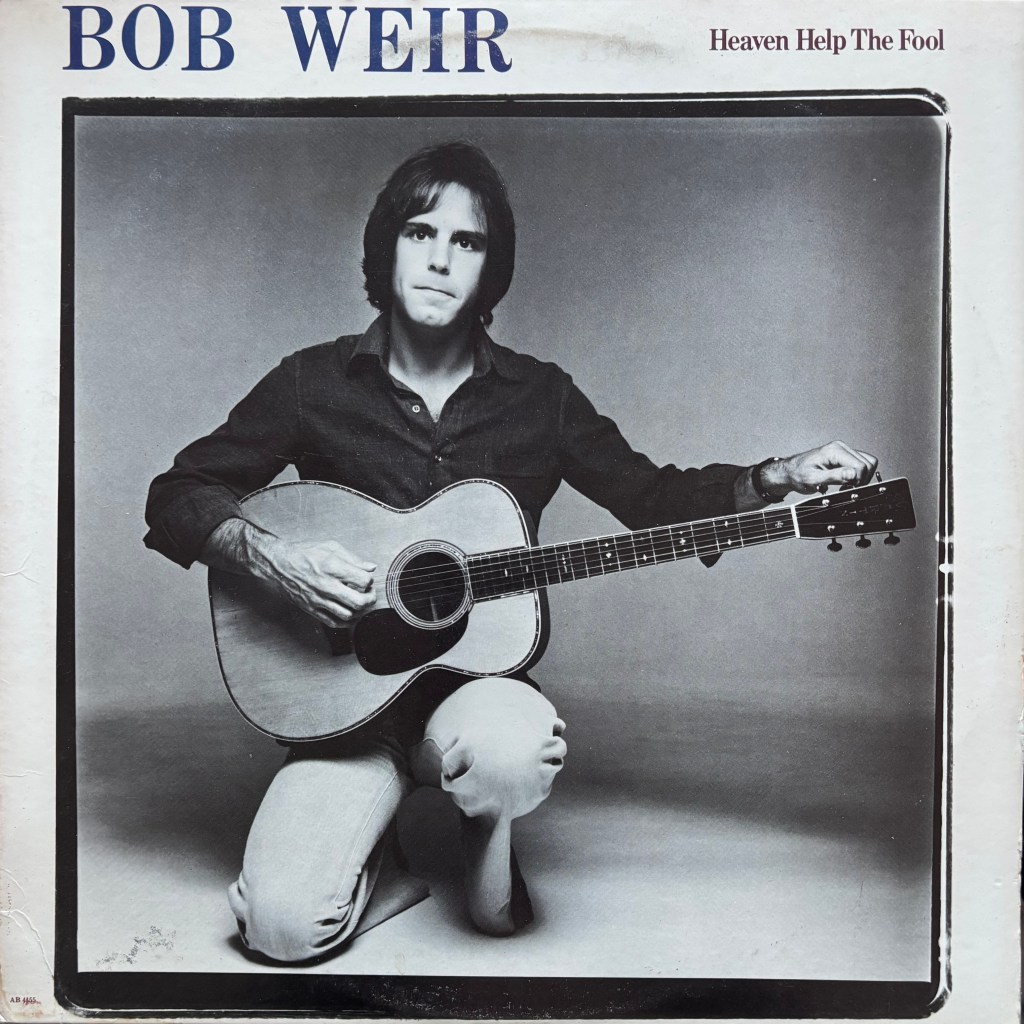

A note about the playlist: I focused mostly on Grateful Dead songs that Weir either wrote or sang, and a healthy handful of Weir’s more impressive solo efforts, all presented chronologically. I own and enjoy his 1978 solo LP “Heaven Help the Fool,” with its excellent opener “Bombs Away,” but for some reason it’s unavailable on Spotify, so you’ll have to find that on your own.