Don’t let ’em tell you that there’s too much noise

When a classic rock artist dies (as so many have in recent years), I like to write a tribute-type obituary here at “Hack’s Back Pages.” Typically, it’s someone whose work I have greatly admired, and I enjoy researching his or her career to perhaps learn a few things I didn’t know, and immerse myself more deeply in their musical repertoire.

Sometimes, though, it’s someone whose work I never cared for, and I struggle to write something complimentary and/or respectful. That happened last week when Paul “Ace” Frehley, lead guitarist for Kiss, died at 74.

Full confession: I never liked Kiss. A couple of years ago, I wrote a piece entitled “They’re just not my cup of tea,” which singled out ten commercially successful rock bands I just can’t stand, and Kiss was one of them. Here’s what I wrote:

“There is almost nothing musical to be heard from this band of costumed showmen. And let’s be clear, even Gene Simmons has said Kiss was born of the notion that it didn’t much matter what they played. It was all about the pyrotechnics, the light show, the sheer volume and, of course, the face paint and faux-threatening poses they struck onstage. To attend a Kiss concert was to be assaulted and overwhelmed by what you saw more than what you heard. Therefore, to listen to a Kiss album was an exercise in futility, for there was little there deserving of your time. But sure enough, the group’s fans lobbied for years until these clowns were inducted in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. As showmen? Well, okay, I guess. As musicians? Not on your life, nor mine.”

So, what to do? I decided it might help to get input from some of my loyal readers, most of whom are pretty savvy music lovers, and most are in my generation (born between 1950-1965). What was their take on Kiss? Did they buy their albums? Did they ever see a Kiss concert?

I found their responses amusing, mostly dismissive, even contemptuous, and I figured it would be illuminating to share them here.

Bob P said, “Never a fan. They must have had something, but I didn’t see it.”

Kevin W. wrote, “Great band for a one-time teenager to smoke pot, drink beer and rock out to. Never saw them live, but had the ‘Alive’ album.”

Paul V concluded, “Their whole shtik left me cold.”

Patty M. noted, “My brother was a fan (age 12-14). His first concert was Kiss and he thought it was the best thing ever…until he discovered other music. I never cared for their gimmick, and their music was not my style.”

Mark F. warned, “Seems best if you don’t spend your time trying to make Kiss interesting enough for a blog entry.”

Andy W. recalled, “When I was in junior high, Kiss was the biggest band in the world. People would come to school in garish Kiss t-shirts. I never liked them one bit. I thought their music was bad.”

Chris A. added, “Saw them once, and it was what I anticipated — lots of makeup, lots of noise, a visually fantastic show, and that was it. Never owned one of their records, and never needed to see them again.”

Ed F. declared, “Kiss sucked! Face paint and heels? Enough said.”

Margie C. revealed, “Don’t like them. Couldn’t tell you the name of any of their songs.”

Glen K. observed, “I was an Alice Cooper fan, and I always thought Kiss was trying to ride the wave he perfected. But they certainly had a following that can’t be ignored.”

Irwin F. opined that writing something laudatory about Frehley or Kiss was “Mission Impossible…the rock and roll equivalent of eulogizing Charlie Kirk.”

Steve R. called Frehley “an ’80s shredder. Not my favorite style.”

Ira L. graciously said, “Not a fan of Kiss, but blessings to his family and all of his fans.”

One reader, Richard K., offered this hilarious anecdote: “In 1980, I was publishing the #1 Lifestyle magazine in Perth, Australia. Kiss came to town and we were sent free 4th-row seats to the concert, which I reluctantly attended. I’d been to many concerts but hadn’t been exposed to the theatrics or volume level of Kiss. I stuffed some candy wrappers in my ear to save my eardrums. At the end of the show, I couldn’t remove the wrapper because it was lodged too far in my ear and had to go the emergency room to remove it. A gossip writer from the Sunday Times heard about this and wrote it up in his column, which was the most embarrassing thing for me. The last thing I wanted was for anyone to know I had been to a Kiss concert!”

Since Kiss has always tended to appeal mostly to pre-teen boys (even the band agreed this was true), perhaps the proper perspective came from Sean M., who is 15 years my junior: “I was pretty young, about 9 or 10, when Kiss was huge in the late ’70s. They completely captured my attention, and the attention of every kid I hung out with. They were my introduction to hard rock. The theatrics made them seem like slightly dangerous superheroes to us. Ace was my first guitar hero. The image of his smoking Les Paul is lodged in my brain. I definitely grew out of them as I got older. My friend and I went to the reunion tour in 1996 because we’d never seen them as kids and, well, we had to. Damned if I didn’t remember every song and every lick that had been stashed away in my brain all that time. Lots of guitarists are now paying tribute to Ace. The guy left a mark.”

**************************

Sean M. has a point. Kiss not only left a mark, they set new records, they changed the boundaries of rock concert presentations, and they were innovative (some might say shameless) marketers.

Between 1974 and 2012, they released 19 studio albums and six live albums, ten of which reached platinum status in the US (a million copies sold). They had less success with singles, but still found a way to chart five songs in the Top 20 on US charts (the highest was #7 for the uncharacteristic romantic ballad “Beth” in 1977).

Other bands before them had unusual visual elements to their stage shows, but Kiss was pretty much the first rock group whose concerts featured everything: overwhelming pyrotechnics displays, glittery costumes, over-the-top stage sets and, perhaps most important, full face makeup that gave each member a specific stage persona. For their first decade of existence, no one knew what they really looked like because they were never photographed, nor appeared in public, without their face paint on.

There were predecessors in rock history who sold all sorts of merchandise featuring the band’s likenesses (The Beatles come to mind), but Kiss was the first to sell stuff at the shows. Not just the usual t-shirts and posters but lunch boxes, games, watches, badges, stickers, action figures, you name it. Call it crass or cheesy, but it earned them a ton of money that helped offset the growing cost of the elaborate staging requirements.

Over the span of their career, Kiss has been classified under the genres of hard rock, heavy metal, shock rock, glam metal and glam rock. They dabbled in a disco-ish pop rock briefly, and even some progressive rock, but mostly kept returning to the hard rock that marked their 1974-1979 heyday. One critic described their stuff as “a commercially potent mix of anthemic, fist-pounding hard rock, driven by hooks and powered by loud guitars, cloying melodies, and sweeping strings.” Love it or hate it, Kiss offered an onslaught of sound that laid the groundwork for both arena rock and the pop-metal that dominated rock in the late 1980s.

You may have noticed that, so far, I haven’t talked about the actual music Kiss recorded and performed. That’s because, with only a couple of exceptions, it was mind-numbingly average, even pretty awful. Before sitting down to write this, I felt that, to be fair, I needed to give their catalog another listen (actually a first listen, for much of it), so I spent a few hours on Spotify (I own none of their albums), and tried, really tried, to find something I liked.

I found five songs. The aforementioned “Beth” is a delicate, melodious tune carried by acoustic guitar and adorned with orchestration, sounding 180 degrees different from Kiss’s typical fare; “Hard Luck Woman,” which is reminiscent of “Maggie Mae”-era Rod Stewart but with far worse vocals; two catchy hard rock radio faves (“Rock and Roll All Nite” and “Shout It Out Loud”) that I don’t mind hearing maybe once every other year; and “I Was Made For Lovin’ You,” which starts like ZZ Top before heading off into an ’80s pop rock groove more like Richard Marx.

Bassist Gene Simmons and rhythm guitarist Paul Stanley were the primary songwriters and singers in Kiss, so I guess they’re mostly to blame for the band’s lame repertoire. Frehley’s guitar chops and rock star attitude, on the other hand, were easily the most satisfying part of their sound and stage presence. The fact that several notable guitarists from recent years spoke out in praise of Frehley’s talents in the wake of his death speaks, um, volumes.

Pearl Jam guitarist Mike McCready added, “All my friends have spent untold hours talking about Kiss and buying Kiss stuff. Ace was a hero of mine, and I would consider him a friend. I studied his solos endlessly over the years. I would not have picked up a guitar without Ace’s and Kiss’s influence. R.I.P. it out, Ace. You changed my life.”

Geddy Lee of Rush said, “Back in 1974, we were the opening act for Kiss, and Alex, Neil and I spent many a night hanging out together in hotel rooms after shows. We’d do whatever nonsense we could think of, just to make him break out his inimitable and infectious laugh. He was an undeniable character and an authentic rock star.”

Tom Morello, the astonishing guitarist from Rage Against the Machine who inducted Kiss into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2014, called Frehley his “first guitar hero.” Said Morello, “The legendary Space Ace Frehley inspired generations to love rock and roll, and love rock and roll guitar playing. His timeless riffs and solos, the billowing smoke coming from his Les Paul, the rockets shooting from his headstock, his cool spacey onstage wobble and his unforgettable crazy laugh will be missed but never forgotten. Thank you, Ace, for a lifetime of great music and memories.”

Frehley was noted for his aggressive, atmospheric guitar playing, and for the use of many outlandish custom guitars that produced smoke or emitted light to each song’s tempo. Guitar World called him one of the best metal guitarists of all time.

As a kid growing up in the Bronx, Frehley was torn between sports and rock music but he soon decided the guitar came first. He became even more certain at age 16 when he saw the Who and Cream at RKO Theater in Manhattan. “The Who really inspired me towards theatrical rock,” he said. “When I saw them, it totally blew me away. I’d never seen anything like it. It was a big turning point.”

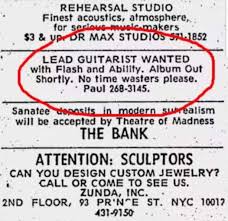

In 1972, Frehley stumbled across a Village Voice ad that forever changed his life: “Lead guitarist wanted with Flash and Ability. Album Out Shortly. No time wasters please.” When he showed up to audition, “I just soloed through the whole song,” he recalled. “They all smiled. We jammed for a few more songs, and then they said, ‘We like the way you play a lot.'”

The band’s distinct stage makeup, black and silver costumes and bombastic show generated instant attention when they started gigging around New York City in 1973, but they didn’t find mainstream success until their 1975 concert album Alive! took off. To a certain segment of young fans, Frehley was the coolest member of the band, and such adulation sometimes went to his head. “When I play guitar onstage, it’s like making love,” he told Rolling Stone in 1976. “If you’re good, you get off every time.”

Frehley and the other band members sometimes had tense disagreements behind the scenes, and Frehley admitted that drug and alcohol abuse played a role in that. “There was so much cocaine in the studio, it was insane,” Frehley recalled in a 2015 interview. “I liked to drink, but once I started doing coke, I really liked to drink more, and longer, without passing out, so I was really off to the races. I made my life difficult because there were so many times I’d walk in with a hangover, or sometimes I wouldn’t even show up.”

By 1982, Frehley simply had had enough. “I was mixed up,” he said. “We were this heavy rock group, but now we had little kids with lunchboxes and dolls in the front row, and I had to worry about cursing in the microphone. It became a circus. I believed that if I stayed in that group I would have committed suicide. I’d be driving home from the studio, and I’d want to drive my car into a tree.”

Interestingly, when all four members simultaneously released solo albums in 1978, it was Frehley who had the only Top 20 single, a remake of the Russ Ballard rocker “New York Groove.” After a spell of inactivity after leaving Kiss, Frehley formed his own band, Frehley’s Comet, who had two modestly popular LPs, but successive releases were met with comparative indifference.

A brief reunion of all four original members at the band’s 1995 “MTV Unplugged” special lead to a massive reunion tour in 1996 where they put the makeup back on, dusted off the old songs, and returned to stadiums and arenas all over the world. In 1998, they cut the new studio LP “Psycho Circus,” but Frehley only played on a single track. “I wasn’t invited to the studio,” he said in 2014. “When you hear Paul and Gene talk about it, they say I didn’t show up. The reason I’m not on any of the songs is because I wasn’t asked. They tried to make it look like I was absent.”

He once again left the band in 2002 following the conclusion of that year’s Farewell Tour. He was replaced by Tommy Thayer, who wore his signature Starman makeup and replicated all of his guitar parts. “Tommy played the right notes, but he didn’t have the right swagger,” Frehley claimed. “He just doesn’t have my same technique.”

Frehley continued performing and recording over the past 20 years but to smaller and smaller venues. In a 2013 interview,, he spoke about the mighty devotion of the band’s fanbase. “They’ve always been there for me through ups and downs. My life has been a roller coaster ride, but somehow I’ve always been able to land on my feet and still play the guitar.”

Considering the testy relationship Frehley had with Simmons and Stanley since 2002, it’s fairly remarkable that the two men did the right thing and released a compassionate joint statement. “We are devastated by the passing of Ace Frehley. He was an essential and irreplaceable rock soldier during some of the most formative foundational chapters of the band and its history. He is and will always be a part of Kiss’s legacy.”

R.I.P., “Spaceman.” Hope you enjoyed your stay on Earth.

****************************

I’ll probably never listen to it again, but for the record, here’s a playlist of selected tracks from Kiss’s albums, and a few from Ace Frehley’s solo releases. You’ll note I didn’t call the playlist “Essential Kiss.”