Just listen to the stories we could tell

This week, I’ve gathered some interesting anecdotes, historical notes, strange coincidences, amusing back stories and personal reflections from rock music’s golden years to share with you all.

**********************

On May 13, 1950, a boy was born prematurely in Saginaw, Michigan, and put on oxygen treatment in an incubator. Evidently, an excess of oxygen aggravated a rare visual condition known as “retinopathy of prematurity,” which caused total, irreparable blindness. The lack of sight seemed to turn to an advantage, as the boy realized his heightened sense of hearing allowed him to acutely absorb music of all kinds. He sang in the church youth choir at age four. In rapid succession, he learned piano, drums and harmonica, all by age nine. No one could have possibly predicted the dizzying heights this prodigy would attain by his mid-20s. Stevland Hardaway Judkins — later Stevland Morris when his mother remarried — became, by 1962, “Little Stevie Wonder,” a true phenomenon who evolved into Stevie Wonder, arguably one of the most important musical artists of our time.

*********************

Wild Cherry was a straight-ahead rock band in 1975, struggling along as they played nightly gigs in clubs around their native Pittsburgh. One night, a group of black patrons approached them during a break and said, “Hey, are you white boys going to ever play any funky music tonight?” Lead singer Rob Parissi immediately sat down and wrote a song around that thought. The group worked on it over the next week, coming up with a dance groove they liked, and found a sympathetic producer at Epic/ Cleveland International to record it. Two months later, “Play That Funky Music” was the #1 song in the nation, ultimately snagging two Grammy nominations in the year disco began its rule of the airwaves.

**********************

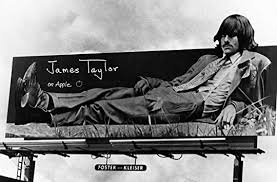

When James Taylor was a young unknown songwriter on the East Coast in the 1967-1968 period, he had little luck getting noticed by record labels and music industry types. Struggling with his insecurities and a predilection for drug use, Taylor decided to go to London for a while to see what opportunities might happen there for him. Sure enough, Peter Asher, a talent scout working for The Beatles‘ new label, Apple Records, heard Taylor’s demos and brought them to the attention of Paul McCartney and George Harrison, who both agreed they should sign him. When Taylor came into the studios to record his music, some of the songs were still incomplete and in need of tweaking. As he worked on “Carolina in My Mind,” he couldn’t help but notice McCartney, Harrison and Ringo Starr in the control booth listening in. Naturally, this unnerved him, but it gave him a lyrical passage he needed for the bridge: “And with a holy host of others standing ’round me…”

*********************

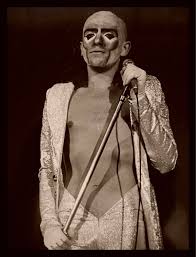

In 1974, Genesis was in the process of writing and recording its opus, “The Lamb Lies Down on Broadway,” when Peter Gabriel was approached by film director William Friedkin, who was then riding high with his hugely successful movie “The Exorcist.” Friedkin was keen on making a science fiction film and was looking for “a writer who’d never been involved with Hollywood before.” As a fan of Genesis, he had read the sleeve notes on the back of the “Genesis Live” LP — a typically fantastical short story by Gabriel — and thought maybe they could collaborate. Gabriel was excited about it, but the other members of Genesis weren’t receptive to him putting the band, album and tour on hold for this side project. When Friedkin heard his offer might result in the demise of Genesis, he backed off, since his sci-fi project was still just a nebulous idea and, as a big fan of Genesis, he wanted the group to continue. We’ll never know what Friedkin and Gabriel might’ve come up with.

***********************

In late 1974, Fleetwood Mac‘s guitarist/singer Bob Welch announced he was departing, leaving remaining members Mick Fleetwood, John McVie and Christine McVie in a bind. They had lost guitarists before; founding member Peter Green had abandoned the group four years earlier, as did Danny Kirwan in 1972. But this time, they had just relocated to L.A. from their native London and were in precarious trouble financially. Maybe this was the end of the line for the once top-ranked British blues band. Fleetwood was determined, though, and went to visit a new recording venue called Sound City. While he was there, he heard a guitar player named Lindsay Buckingham working on material in one of the studios. Intrigued, he introduced himself, and within the hour, he asked Buckingham if he’d like to join Fleetwood Mac as their new guitarist. “That sounds great, we’d love to,” he replied, “because my girlfriend comes with me.” He was referring, of course, to Stevie Nicks, the singer-songwriter who had been his lover and professional partner for several years. Fleetwood hesitated about accepting Nicks as well but then decided, what the hell, let’s go for it. Eighteen months later, the group that had never managed much chart success in the US had the #1 album in the country.

*********************

David Robert Jones, born in working-class England in 1947, showed an interest in music at an early age, learning recorder and ukulele and singing in the school choir. He especially shone in a “music and movement” class that presaged his mesmerizing stage shows. His father changed his life the day he brought home a stack of 45s by American R&B artists. “I thought I’d heard God,” said the boy when he heard “Tutti Frutti.” He moved through a number of ragtag rock bands in his teen years, playing saxophone and guitar and often handling lead vocals, even winning a contract or two along the way, but nothing came of the records from that period. In 1966, Davy Jones of The Monkees became a celebrity, so David Jones knew he’d better change his name and, in honor of “the ultimate American knife” he’d always admired, he became David Bowie.

*********************

Some people are so damn talented. Steve Winwood was only 15 when he joined his older brother in the Spencer Davis Group, where he played keyboards and sang with an expressive, high, bluesy voice that even then drew comparisons to the great Ray Charles. At 18, he wrote two songs with Spencer Davis that became Top Ten hits in the US and the UK, “Gimme Some Lovin'” and “I’m a Man.” At 19, he formed Traffic, one of the most inventive British bands of the late ’60s. At 21, he joined forces with Eric Clapton in Blind Faith, producing amazing tunes like “Can’t Find My Way Home” and “Sea of Joy.” He then reformed Traffic at 22 to produce more classic albums like “John Barleycorn Must Die” and “Low Spark of High-Heeled Boys.” By the time he was only 26, he disbanded Traffic and took a well-deserved break for a few years. Then at 32, he finally kicked off a hugely successful, Grammy-winning solo career. Incredible.

**********************

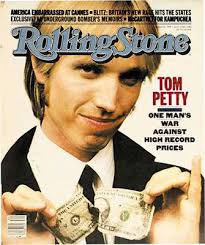

Savvy bands know that relentless touring is the best way to increase awareness and support for their music. Tom Petty and the Heartbreakers, following the release of their breakthrough LP, 1979’s “Damn the Torpedos,” certainly knew this, and their venues and crowds got commensurately bigger as they did so. As the group returned to the studio, MCA Records decided they would (literally) capitalize on the band’s success by slapping a $9.98 “superstar pricing” on the next release (“Hard Promises”) instead of the then-customary $8.98. Petty balked at the obvious greed, and withheld the master tapes in protest, which helped make the issue a popular cause among music fans. When he threatened to rename the album “$8.98” to drive home his point, the label reluctantly backed down.

********************

Everyone has heard the story about how the introduction of Yoko Ono into John Lennon’s life was a contributing factor leading to the breakup of The Beatles. Probably less known is the story of how singer Rita Coolidge played a role in the premature breakup of Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young. To be fair, CSN&Y was a volatile mix of egos from the get-go, with each member brimming over with musical talent and confidence. They each felt their songs were better than those of the others, and each wanted more than just two songs apiece per album, and more time in the spotlight during concert performances. In the midst of this tense atmosphere, Stephen Stills met Coolidge, had become very attracted to her, and was eager to build a relationship with her. The twosome arrived at a party one night, and within minutes, Graham Nash turned on his British charm and spirited Coolidge away. This enraged Stills, and it proved to be the straw that broke the camel’s back. He swore he would never work with Nash again, and headed off to pursue a solo career. CSN(&Y) split up soon after that, and though they would reunite years later, the momentum they’d built was lost, and things were never quite the same between them. David Crosby wrote about the soap opera of it all in his 1971 solo track “Cowboy Movie.”

**********************

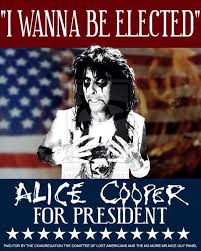

In the election year of 1972, shock-rocker Alice Cooper was getting plenty of exposure with the single “Elected” and its just-in-fun lyrics about running for president. The rock journalists knew the whole thing was just a joke, but a few hard news reporters from Time Magazine and The Washington Post starting asking him his opinion on the political issues of the day. One demanded to know which candidate he intended to support in November. He laughed out loud and responded, “If you’re listening to a rock star in order to get your information on who to vote for, you’re a bigger moron than they are.”

**********************

In the early ’60s, Pete Townshend, Roger Daltrey, John Entwistle and Keith Moon had been playing club gigs using the name The Detours and, for a brief spell, The High Numbers. Nobody was particularly enchanted with those names, but they kept on until something better came to them. One night, Townshend, who still lived at his parents’ house, was heading out the door to see another band play at a local club. His hard-of-hearing grandmother, who also lived in the Townshend household, asked him where he was going. When he mentioned the name of the band, his grandmother shot back, “You’re going to see the who??” A light bulb went off in Townshend’s head, and after a quick huddle with the rest of the group, The Detours officially became The Who.

**********************

In 1969, a band known as Steam recorded a song called “It’s the Magic in You, Girl,” selected by their label as a potential hit. They were then told, “Okay, now record something else, anything at all, to put on the B-side of the single. It can be instrumental, it doesn’t matter. Whatever you want.” They started doing a light, accessible groove, jamming for 20 minutes while the singer added a bunch of “na na na”s and other off-the-cuff lyrics, and they were done. The producer edited it down to the best three minutes, slapped it on the back of “It’s the Magic in You Girl,” and shipped it out. As it turned out, DJs thought the A-side was lame and ignored it, but they were taken by the catchy ditty on the B-side. Within a few weeks, “Na Na Hey Hey Kiss Him Goodbye” was the #1 song in the country.

***********************