When we stand together as one

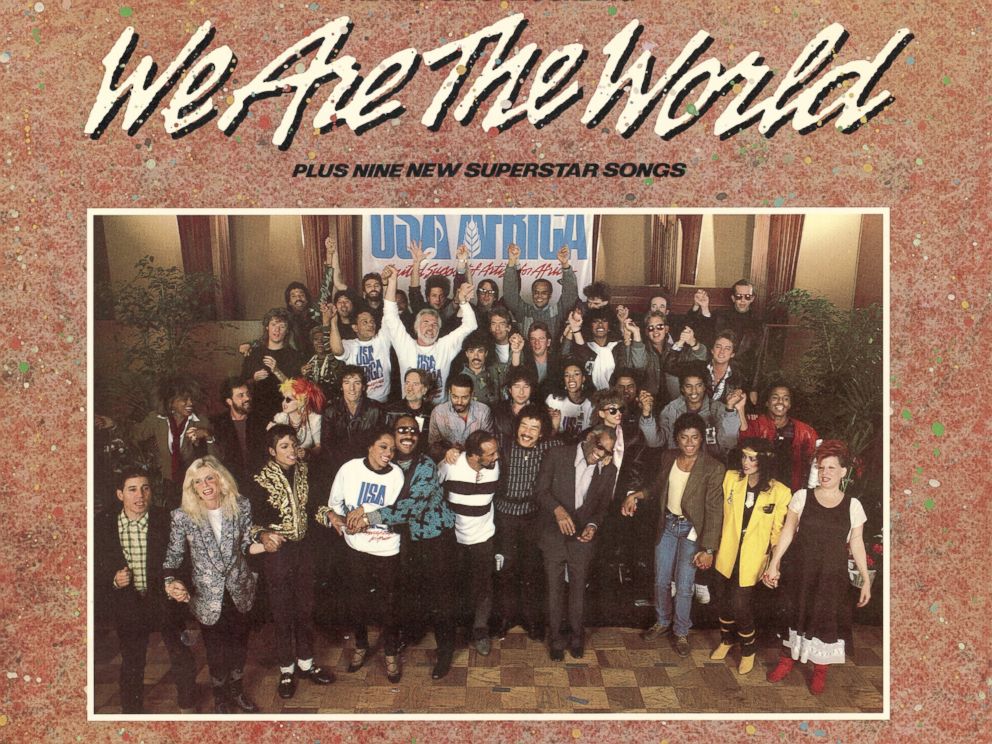

Forty years ago this week, one of the most extraordinary collaborations in popular music history occurred in Los Angeles when 45 performing artists — 30 of whom were the biggest stars of that era — convened in a Hollywood studio to record a song for charity that still ranks as one of the music industry’s biggest commercial successes.

“We Are The World,” written by Michael Jackson and Lionel Richie, became the fastest-selling U.S. single of all time and ultimately raised upwards of $40 million in humanitarian aid to fight the famine that had claimed a million lives in Eastern Africa. Considering the logistical challenges and the outsized egos of many of the people involved, perhaps the most remarkable thing about it was that they were able to pull it off at all.

*********************

In November 1984, Irish singer-songwriter Bob Geldof saw a BBC report about a terrible famine wreaking havoc on the impoverished population of Ethiopia. Motivated to do something about it, he contacted Scottish songwriter/producer “Midge” Ure about pulling together musical artists from across the United Kingdom to record a song he was writing to raise money to combat the dire situation.

They were able to enlist Sting, Bono, Boy George, Phil Collins, George Michael, and members of Duran Duran, Spandau Ballet and Geldof’s Boomtown Rats to show up at a London studio where, in one day, they became Band-Aid and recorded “Do They Know It’s Christmas?”, which was released a couple weeks later and became one of the biggest singles in UK history, raising nearly $10 million dollars, wildly exceeding Geldof’s expectations.

In the U.S., Harry Belafonte, the iconic singer/actor/social activist, watched this closely and was inspired. He approached Ken Kragen, LA’s most connected music manager. “Thousands of people are dying in Africa, right now,” Belafonte said. ”We can, we must, do something about that. Maybe we need to stage a charity concert to provide both moral and financial support.”

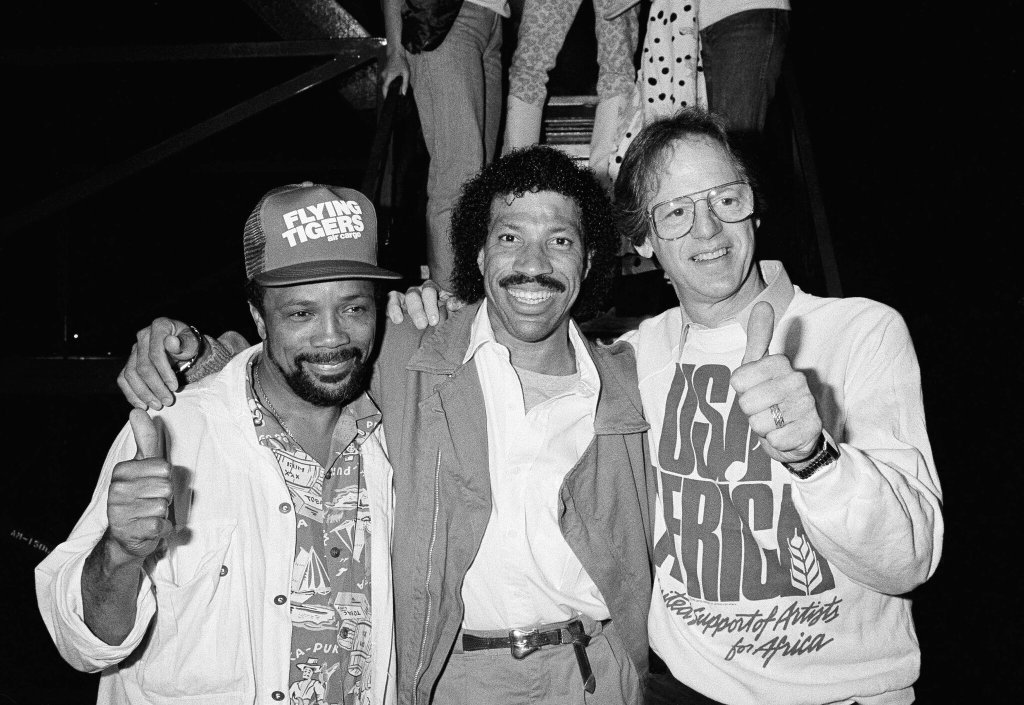

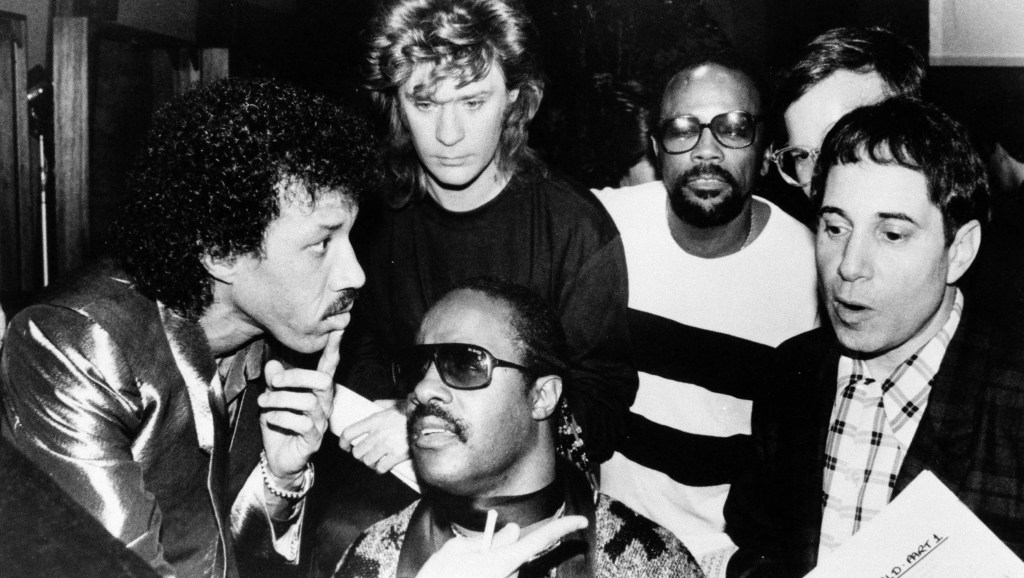

Kragen was skeptical. “I doubt that a concert would make as much impact or raise as much money as a charity single,” he said. “We could take Geldof’s concept and do it here, with the greatest stars in America.” Kragen approached Richie, his client at the time, who embraced the idea and suggested they get the great Quincy Jones to produce it.

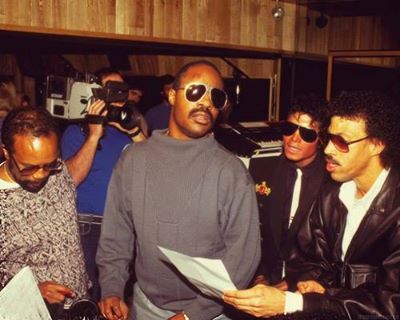

“Quincy is a master orchestrator — of music and of people — and he had the respect of every musician on the planet,” said Richie. “Quincy immediately thought of Stevie Wonder and figured the two of us could write the song.” Wonder was busy with his own project, but Jones found Michael Jackson very receptive to getting involved, so Richie and Jackson huddled to decide what kind of song it should be.

“A rocker? A ballad?” mused Richie. “We knew it needed to be relatively easy to sing, and memorable, and anthemic. We ended up with a mid-tempo pop melody that would give an array of stars the chance to show off their vocal chops. Ultimately, we wanted it to be big and almost stately.” Over the course of a week, the twosome fashioned the melody, toyed with the instrumentation (piano, drums, strings), tweaked the words for verses and chorus. The chorus and title, “We are the world,” was “an appeal to human compassion,” said Jackson, “designed to be sung together as children of the planet coming together as one.”

Meanwhile, Jones and Kragen were brainstorming about who they wanted as their singers beyond Jackson, Richie and Wonder. Because this was about black populations in Africa who were starving and dying, they had originally focused on the need to get black artists involved, but they soon saw the wisdom in broadening their scope to include white artists as well. “Artists’ schedules are typically planned months in advance, so we wondered how in hell we could get them to participate,” said Kragen. “That’s when we landed on the perfect solution: The American Music Awards.”

The AMAs were already slated for Monday, January 28, in Los Angeles, and coincidentally, Richie had been invited to serve as the host. “Those awards cover multiple genres — rock, R&B, pop, country — so that event would be bringing many major stars to LA as nominees and as presenters,” said Jones. “It’s already on their schedules to be in town. We knew we needed to schedule the session for that night, after the live awards show. It was our only choice.”

They knew they had to work fast, so they got on the phones and reached out to some of the biggest names at that time, and got a “thumbs up” from Diana Ross, Hall and Oates, Cyndi Lauper, Ray Charles, Paul Simon, Kenny Rogers, Steve Perry, Tina Turner, Willie Nelson, Kenny Loggins, Billy Joel, James Ingram, Dionne Warwick, Kim Carnes, Al Jarreau and Huey Lewis. Some artists were on tour and unavailable, or were hesitant to be a part of it: Madonna, Prince, Van Halen, David Byrne, among others.

The organizers also wanted Bruce Springsteen, who would be completing a huge tour the previous day. “I usually take time off after a tour, but I knew this was important, so I told ’em, ‘I’m in,'” he said. With Springsteen signed up, they set their sights on Bob Dylan. “He’s the consummate ‘concerned musician,'” said Richie, “so he was a natural fit, but he’s kind of a control freak and likes to call his own shots. But we got him to agree to be there.”

Jones, Jackson, Richie and Wonder convened in a secret session on January 22 at Kenny Rogers’ Lion Share Studio to record the basic backing tracks with guide vocal. Jones used pianist Greg Phillinganes, bassist Louis Johnson and drummer J.R. Robinson, who had worked together on Jackson’s “Don’t Stop ‘Til You Get Enough” session, among others. Richie and Jackson added their vocals in six takes, and they made copies of the tape to ship overnight to the invited performers so they could learn the song beforehand.

Kragen and Jones had secured A&M Recording Studios in Hollywood for the all-important January 28 post-AMA Show session. They made it crystal clear to everyone involved that there could be no leaks about where this was going to take place. “A&M was the perfect location, with phenomenal sound,” Kragen said, “but if that showed up in the press, it could destroy the project. We couldn’t have a mob of media and onlookers there when the stars arrive. This had to be hush-hush.”

Jones brought in veteran vocal arranger Tom Bahler to help determine which artist would sing which line of the song. “That was a real challenge,” Bahler recalled. “Nobody had ever had 45 people in the same room before, and there were going to be so many strong creators there. Stevie Wonder, Diana Ross, Cyndi Lauper, all these strong-willed creative people…it had the potential to be chaos. So we had to have a leader, and that was Quincy. He had the ability to command everyone’s respect and keep people focused on the mission.”

Said Bahler, “Quincy told me, ‘Lionel was the first one to write this, so he should be the first voice we hear. And then because Michael came in and they finished it together, Michael should sing the first chorus.’ Then Quincy chuckled and said to me, ‘Then I think you should bring Diana in for the second half of the first chorus, because some people think she and Michael are the same person!’ Other than that, the rest was left up to me.”

Bahler studied the vocal styles and ranges of the artists who would be on the record, trying to match each line to the right singer. “Some of them would have only half a line to sing, but still, it had to be right for their sound, they style, their range. I put Tina on a low-register line because she has such warmth down there. Steve Perry, his high range, he’s just electrifying up there. Kenny Loggins could sing with an edge, so it would sound great coming after Springsteen. Huey Lewis, I love Huey, but not everybody was going to get a solo line. All these sorts of things had to be taken into account.”

To my ears, the thing about “We Are the World” that still sends chills up my spine is the juxtaposition of such varied, quality voices, one line after another. Mahler did a simply spectacular job selecting the right singers in various groupings on the verses and choruses. First came Richie, Wonder and Paul Simon, followed in verse two by Kenny Rogers, James Ingram, Tina Turner and Billy Joel. Brilliant! After the Jackson/Ross pairing on the first chorus, the third verse brought the unusual transition of Dionne Warwick to Willie Nelson to Al Jarreau, followed by the thrilling second chorus — Springsteen’s growl and the soaring pop of Kenny Loggins, Steve Perry and Daryl Hall. Incredible! Then Jackson returned for a line before handing off to Huey Lewis, Cyndi Lauper and Kim Carnes, which segues into the third chorus, where 30 to 40 voices sing in unison for the first time. So powerful!

The grand choir of voices for the chorus in the song’s second half would include not only those who would sing solo lines, but others who were there like Bette Midler, Waylon Jennings, Lindsey Buckingham, Smokey Robinson, Jeffrey Osborne, Sheila E, John Oates, Dan Aykroyd, The Pointer Sisters, the rest of The Jackson Five, the members of Huey Lewis’s band The News, and Belafonte and Geldof.

Recalled Springsteen, “The song itself was very broad, which it has to be if you’re carrying all those different voices and ranges.”

Richie said he expected Jones would want each soloist to go into the booth one by one to sing their line, but Jones told him, “Oh hell no, we’ll be here for three weeks. We’ll put everyone in a circle in the room with all the mics, and everyone’s going to sing looking at each other.” Richie’s jaw dropped at that, but Jones said, “Taking this kind of chance is like running through hell with gasoline drawers on, I know, but I’m not afraid. Still, it’s deep water. We’ll have to clamp down on outside noises, laughing, jewelry rattling, even creaks on the floor from feet tapping.”

It’s astonishing, really, when you think about what Richie was being asked to do on January 28th. He had to host the AMAs, and this was back when network TV was the only thing happening, so it was a very big deal. He was required to be charming at the pre-show press conference. He performed two songs during the show. He even had to make graceful acceptance speeches when he ended up winning several major awards. He had to maintain his cool on live TV for three-plus hours…and then he had to dash off to this high-stakes, high-pressure secret recording session and help Jones keep some semblance of order and positivity among all these assembled prima donnas.

Jones had a brilliant idea before anyone arrived at the session. He made a sign and hung it on the studio entrance that admonished everyone: “Check your egos at the door.” Somehow, for the most part, it seemed to work, partly because many of the participants were uncertain and a little nervous about what was going to happen, or in awe of the legendary talent that was assembled.

Here are some quotes from those who were there:

Smokey Robinson: ”Everyone you could think of who was in show biz at that time was at the recording.”

Huey Lewis: “A car took me there. I had no clue who was going to be there. When I realized it was the cream of the crop of pop music at that time, well, it was overwhelming.”

Bruce Springsteen: “It was intoxicating just to be around that group of people.”

Billy Joel: “Whoa, that’s Ray Charles. That’s really him. That’s like the Statue of Liberty walking in.”

Kenny Loggins: “When I saw Diana Ross, I thought, ‘Okay, we’ve hit a different echelon here.’ At one point, we’re on the risers, all these legends, and Paul Simon, who’s on one of the lower steps, looks up and says, ‘If a bomb lands on this place, John Denver’s back on top!'”

Said Richie, “By about 10 p.m., everyone’s assembled. We could all feel the incredible energy in the room, but also a low hum of competition. Let’s not pretend the egos weren’t still there. I found it interesting that the biggest stars seemed almost timid in that environment.”

Jones summoned Geldof to the front of the room to remind everyone of the meaning behind the mission. “I don’t want to bring anybody down,” he said, “but maybe it’s the best way to make what you’re feeling why you’re really here tonight come through in this song. Let’s hope it works.”

Richie recalled, “The tension was huge because we didn’t have a lot of time. Technically, we need to be really together, and we had to move fast. We had one night only to get this right.”

With 60-plus people in the room and several 5,000-watt lights so the proceedings could be captured on film, it got pretty warm, and people had to be quiet and be team players. “Shooting video and recording the song at the same time,” noted Richie. “Could anything go wrong? Absolutely! We were flying by the seat of our pants. I was working the room, keeping people in good spirits, running on pure adrenaline.”

Jones was adamant about silencing any troublemakers who wanted to make changes. “With 45 artists, you’ll have 45 different versions of the song. My job was, under no circumstances will we allow this to veer off what it is. When Stevie piped in with, ‘I think we need some Swahili somewhere in the song,’ I had to dissuade him. Geldof told him, ‘There’s no point in talking to the people who are starving. You’re talking to the people who’ve got money to give.” That’s when Ray Charles stood up and said, “Okay, ring the bell, Quincy!”, which was his way of saying, “Let’s get going here.”

They recorded the full-choir chorus sections first, which took about two hours. At one point, Jones publicly thanked Belafonte for being the impetus behind the project, and everyone began singing the words to his signature song from 1956: “Day-o, day-o, daylight come and me wanna go home.” This broke the tension, and the next take was successful, which allowed 15-20 people to leave, thinning out the room a bit.

Then came the solo lines, which generally went more smoothly. Richie said, “Quincy was right about that intimidating circle of life, everyone facing each other. When it’s your turn, you’re going to give 200% because the whole class is looking at you and you wanted so badly to get it right!”

By then, it was approaching 5:00 a.m. Saving the best for last, Dylan, Wonder, Springsteen and Ray Charles were tapped to do the solos during the repeated choruses as the song heads slowly toward the fadeout. (Truth be told, Charles and Wonder came in a couple days later to punch in better performances, but Springsteen and Dylan did theirs that night.)

Said Bahler, “God must have tapped me on the shoulder to take the record to another level by suggesting that I ask Bruce Springsteen to supply solo answers to the choir melody on the title choruses. Because of the textures and intensity of his truly unique vocal equipment, especially in this register, he was the perfect person for it.” Later, Jones chose to cut out the choir for nearly a minute and make that part a call-and-response between Wonder and Springsteen, and it worked beautifully.

Perhaps not surprisingly, Dylan turned out to be the most uncomfortable with his assignment, struggling to come up with what they were looking for from him on the line “There’s a choice we’re making, we’re saving our own lives, it’s true we make a better day, just you and me.” It was Stevie Wonder who helped ease Dylan’s anxiety, mimicking Dylan’s unique vocal approach, which caused him to chuckle, “I must be in a dream, man.” When he finally nailed it, he sighed, “That wasn’t any good,” but Jones and the others loved it.

After everyone had left, said Bahler, “Diana Ross was still there, and I heard her crying. Quincy said, ‘Diana, are you okay?’ She said, “I just don’t want this to be over.”

The finished product received mixed reviews. “‘We Are The World’ sounds an awful lot like a Pepsi jingle,” grumbled one critic. Another said, “The superstars calling themselves USA for Africa were proclaiming their own salvation for singing about an issue they will never experience on behalf of a people most of them will never encounter.” But Stephen Holden of The New York Times wrote, “It’s a simple, eloquent ballad, a fully-realized pop statement that would sound outstanding even if it weren’t recorded by stars.” He praised the “artfully interwoven vocals that emphasized the individuality of each singer.”

Distributing food in Ethiopia turned out to be a logistical and political nightmare, and some of the money raised was inevitably squandered. And there’s no denying that, in some circles, the project was perceived to have a certain amount of distasteful self-congratulations about it. But Jones had this to say: “Music is a strange animal. You can’t touch it, can’t smell it, can’t eat it. It’s just there. ‘Beethoven’s 5th’ keeps coming back for 350 years. Music has a very powerful spiritual energy, and in this case, it definitely rescued a lot of lives.”

An important footnote: Much of the information and quotable material found in this post were gleaned from a fascinating, must-see documentary, “The Greatest Night in Pop,” directed by Bao Nguyen, which debuted last year on Netflix and is still available there. One review called it “a briskly paced celebration of a one-of-a-kind musical moment, which uncovers new stories while reminding viewers of the humanitarian vision that made it all happen.” I strongly urge you to check it out.