Are you reelin’ in the years?

We are told that there are about a dozen momentous events in our lives that virtually everyone experiences: Going off to kindergarten. Our first kiss. Graduating high school. Losing our virginity. Our wedding day. The births of our children. The deaths of our parents. Our children’s weddings. Retirement. The births of grandchildren.

This weekend, against all odds, I am alive and eager to be celebrating another major life event: my 50th high school reunion. I was quite the party boy for many years, and some of my peers wondered if I’d still be around when this day arrived. What a gas to gather with my long-ago classmates — some of whom are lifelong friends, others I haven’t seen since graduation day — to share memories of the old days and share tales of what we’ve been up to in the five decades since.

For those of us who graduated from high school and headed off to college during the 1973 calendar year, memories of the music of those 12 months seem split between the albums that graced our turntables at home and those that were played in our college dorm rooms. For instance, Elton John gave us two albums in ’73, and while “Don’t Shoot Me, I’m Only the Piano Player” is a senior-year classic, “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road” feels more like a college-freshman staple.

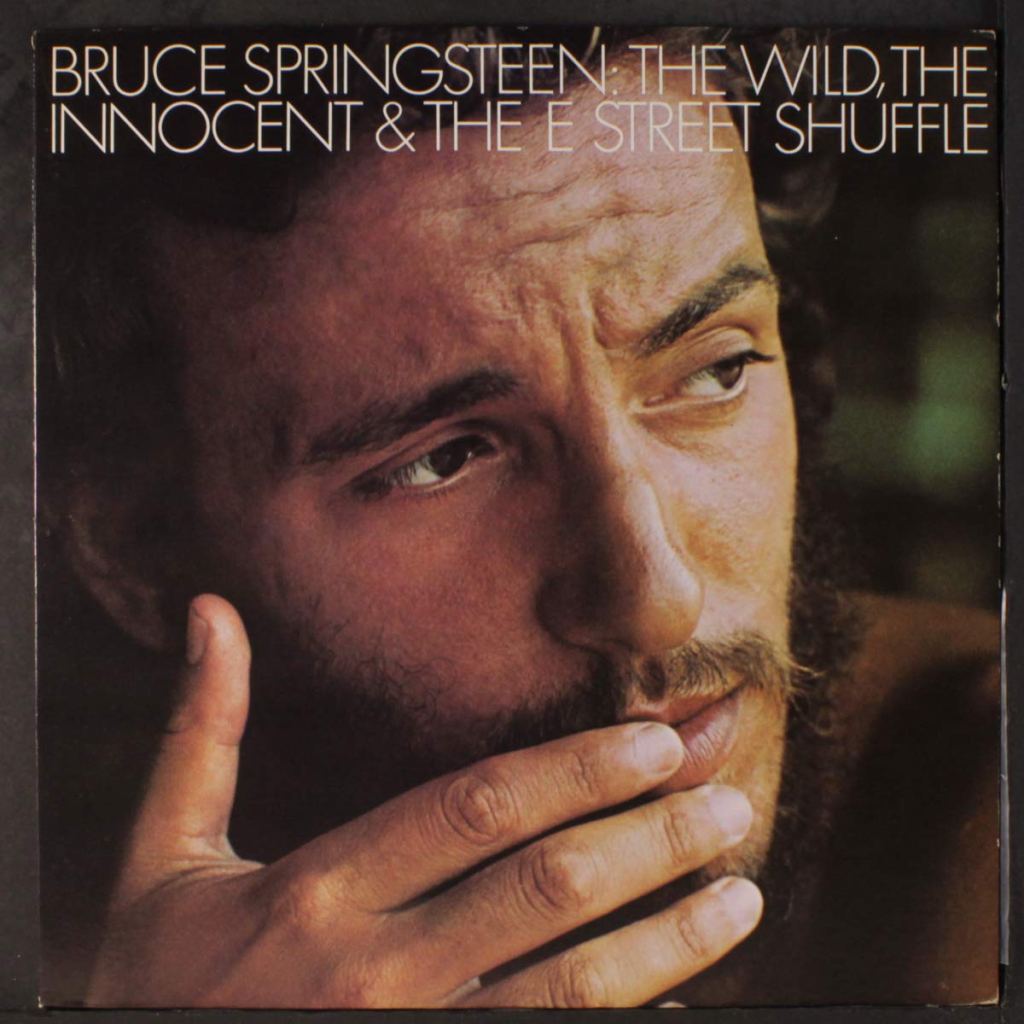

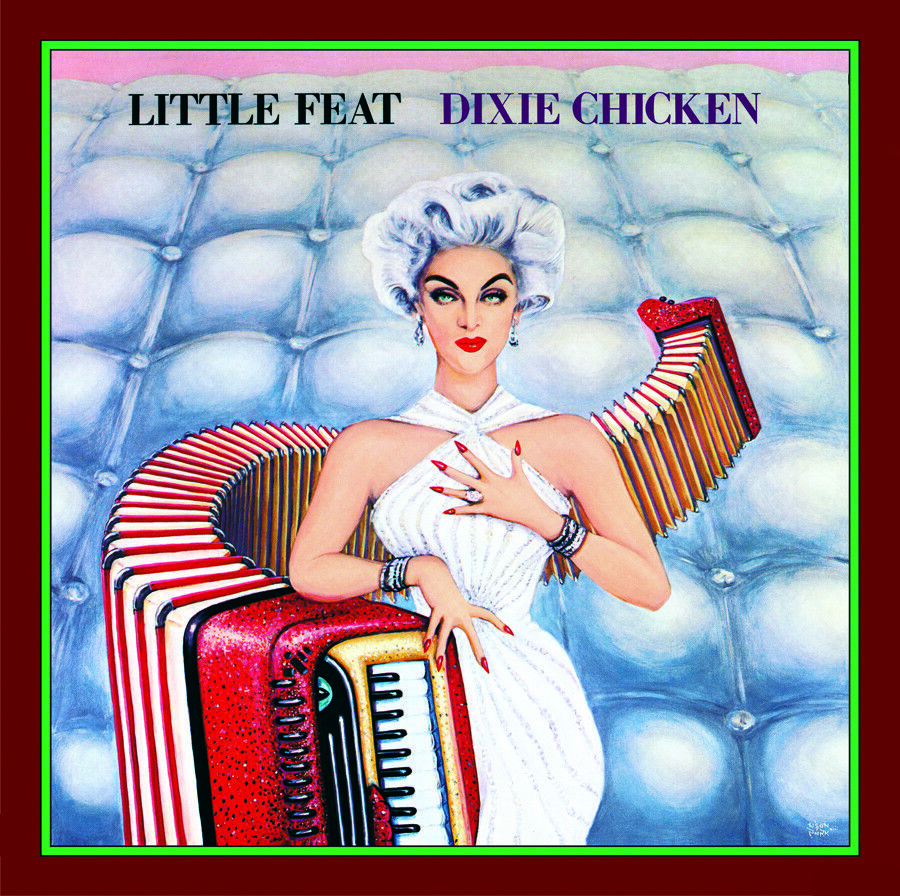

There are also plenty of albums released in 1973 that went under my radar at the time but I became very fond of years later when exposed to them (Tom Waits’ “Closing Time,” Little Feat’s “Dixie Chicken,” Springsteen’s “The Wild, The Innocent & The E Street Shuffle”).

It was a bumper crop of incredible records that were released between January and December of 1973. Upwards of 550 LPs came out, and while some were ignored or instantly forgotten, many dozens, maybe 150 or so, became integral parts of not only our album collections but our permanent musical memories as well.

Trying to whittle down that many candidates to a “baker’s dozen” list of 13 that comprise my choices for the Best Albums of 1973 is damn near impossible. That’s why they’re shown in random order, not ranked #1, #2, etc. I have also included a second list of “honorable mentions” that is more than twice as long as the winners’ list. Some of my readers will no doubt prefer some of those discs instead of my selections…and that’s okay. This is merely a fun, wholly subjective exercise, and I invite you to make your own lists on your own blogs!

At the end, there are two Spotify playlists. The first offers four songs from each of my 13 Best Album choices. The second offers two tracks from each of the 25+ honorable mentions. If you were coming of age in 1973, as I was, I expect you’ll totally enjoy the memories these albums and songs evoke.

***********************

“Innervisions,” Stevie Wonder

Since his debut at age 12 in 1963 through the rest of the Sixties, Little Stevland Morris had earned his stage name Stevie Wonder with one of Motown’s best voices and perhaps the most expressive harmonica playing ever. Most people, though, weren’t prepared for the groundbreaking sounds and songs found on 1972’s “Talking Book” with its hit singles “Superstition” and “You Are the Sunshine of My Life.” Somehow he topped that with the extraordinary “Innervisions” in the summer of ’73. It’s a virtual one-man show — he produced it, sang it, played piano, synthesizer, bass and drums, and wrote all the music and lyrics, and it’s not only revolutionary, it’s still captivating and vital 50 years later. There are ballads (“Visions,” “All in Love is Fair”), gritty urban funk (“Living For the City”), joyous odes to love (“Golden Lady”), political shots (“He’s Misstra Know-It-All”) and a pair of hugely popular dance singles (“Higher Ground,” “Don’t You Worry ‘Bout a Thing”). As one critic put it, “Is the joke on us that a blind man not only romps through visual metaphors, but makes an album more colorful than anything your eyes will get you—funk, soul, and Latin rhythms dancing with keyboards that are so bright and intense they’ll never sound dated?”

“The Dark Side of the Moon,” Pink Floyd

If you smoked weed in the ’70s, you not only owned this album, you memorized every groove. You even knew you could synch it up with “The Wizard of Oz” for some mind-blowing parallels. Pink Floyd’s chief songwriter Roger Waters had been profoundly affected by the mental deterioration of his friend and co-founder Syd Barrett five years earlier, and with “Dark Side of the Moon,” the group created an astonishing thematic work that explores madness, greed, ennui and the cosmos with an unequaled sonic mastery. Credit producer Alan Parsons for much of the technical wizardry, but each band member made important contributions to the overall sound, particularly David Gilmour’s spacey vocals and sublime guitar solos. Bringing in singer Clare Torry to put her vocal acrobatics (no words, just wailing and cooing) on “The Great Gig on the Sky” was a stroke of genius. The use of heartbeats, ticking alarm clocks, loudspeaker voices and provocative speech (“There is no dark side of the moon, really; matter of fact, it’s all dark”) makes for an incredible listening experience. It became one of the best-selling albums of all time.

“The Captain and Me,” The Doobie Brothers

This boogie band from San Jose got a lot of airplay in 1973, both from their 1972 LP “Toulouse Street” (“Listen to the Music” and “Jesus Is Just Alright”) and their excellent follow-up album “The Captain and Me.” Doobies guitarists Tom Johnston and Patrick Simmons constituted a powerful one-two punch as songwriters and singers, with Johnston providing the bulk of their repertoire and lead vocals on the hit singles (“Long Train Runnin’,” “China Grove”) as well as strong album tracks like “Natural Thing,” “Ukiah” and the title cut. Simmons contributed the more melodic, nuanced songs like “Clear as the Driven Snow” and my favorite Doobies song of all, “South City Midnight Lady.” Steely Dan’s Jeff “Skunk” Baxter, who became a full-fledged Doobie Brother a year later, added the sweet pedal steel guitar, and Little Feat’s Bill Payne can be heard playing piano, organ and electric piano on multiple tracks. The Doobies’ career arc, which included “phase two” with Michael McDonald assuming a prominent role, continues to this day, but for my money, “The Captain and Me” remains their most consistent album.

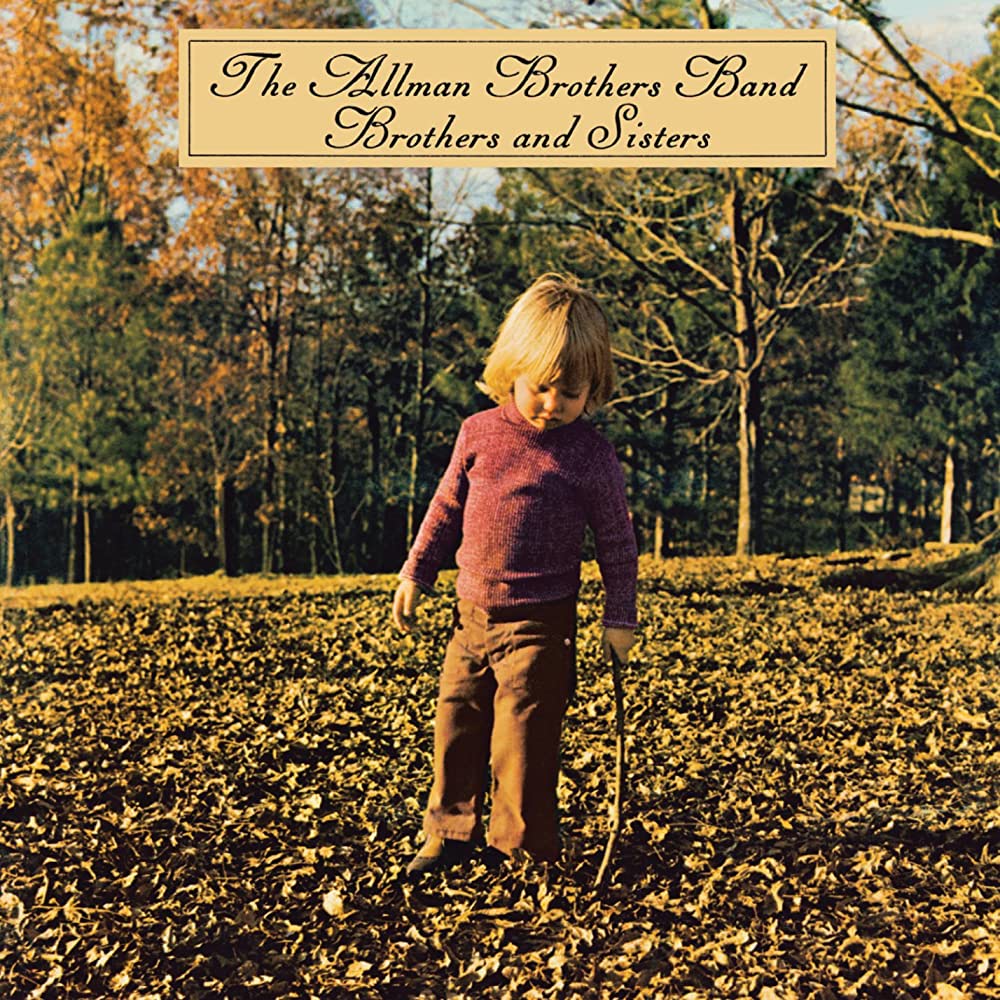

“Brothers and Sisters,” The Allman Brothers Band

Over the course of three years (1969-1971), the six members of The Allman Brothers Band toured continuously, honing their superlative, blues-based talents into an incredible whole that, on some nights, had no peer anywhere. Their spiritual leader, guitar virtuoso Duane Allman, spurred them on to unimaginable heights, culminating in the greatest live album ever made, “At Fillmore East.” Then, suddenly, Allman was gone, killed in a motorcycle accident. The band somehow soldiered on until bassist Berry Oakley died under eerily similar circumstances a year later. Organist Gregg Allman and guitarist Dickey Betts refused to lie down, instead taking the reins and, with pianist Chuck Leavell now on board, they released their best studio album, “Brothers and Sisters,” which reached #1 in the autumn of ’73. Both pop and country radio couldn’t get enough of “Ramblin’ Man,” featuring Betts and guest Les Dudek on dueling lead guitars, and the relentless, driving instrumental “Jessica,” with Leavell and Betts soloing their hearts out. Allman’s bluesy vocals on “Wasted Words,” “Come and Go Blues” and “Jelly Jelly” sealed the deal.

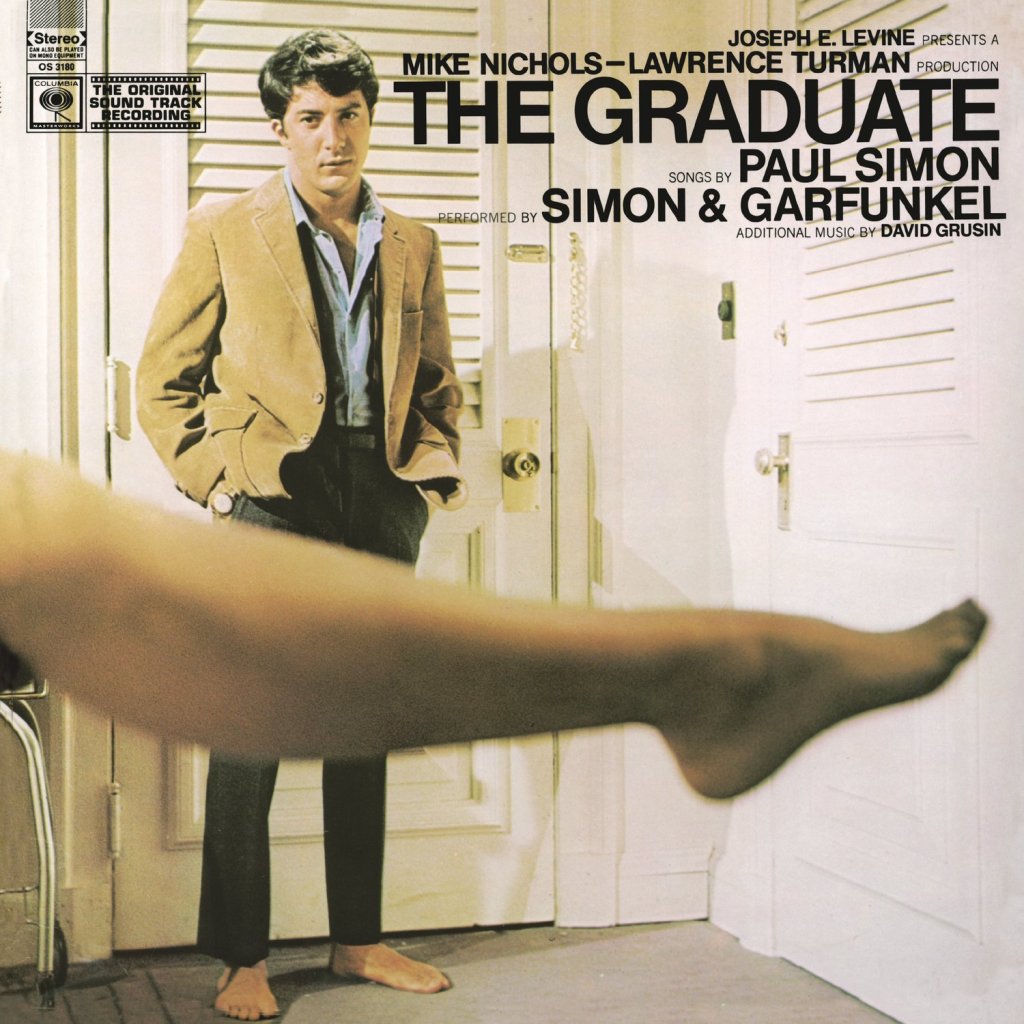

“There Goes Rhymin’ Simon,” Paul Simon

One of the finest songwriters of the past half-century, Simon was first known for his angst-ridden, literary lyrics about isolation, homesickness, grief and depression (“The Sounds of Silence, “Homeward Bound,” “I am a Rock”). But during his days with erstwhile singing partner Art Garfunkel, he showed flashes of whimsy and hope behind all that introspection (“Feeling’ Groovy,” “Bridge Over Troubled Water,” “Cecilia”). He began branching out into more diverse musical genres, and by the time he released his second solo album, “There Goes Rhymin’ Simon,” in the spring of ’73, he demonstrated command of everything from doo-wop (“Tenderness”) to blues (“One Man’s Ceiling is Another Man’s Floor”), from reggae (“Was a Sunny Day”) to Dixieland (“Take Me to the Mardi Gras”), from majestic folk (“American Tune”) to vivacious gospel (“Loves Me Like a Rock”). Throw in an engaging lullaby (“St. Judy’s Comet”) and a stunning love song (“Something So Right”), and you have a veritable encyclopedia of musical styles. He would achieve so much more over the coming decades, but this remains Simon’s most satisfying work.

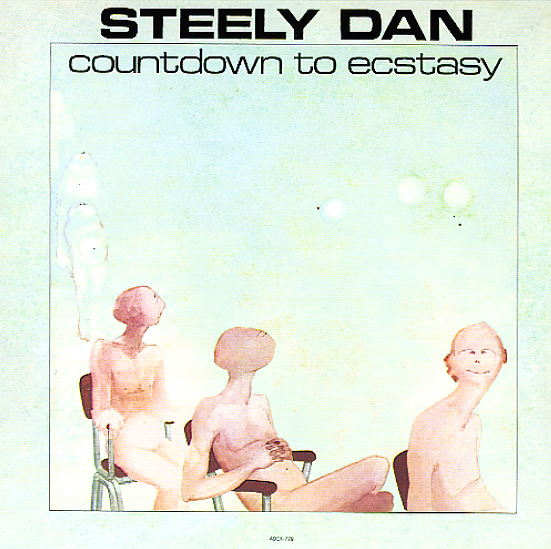

“Countdown to Ecstasy,” Steely Dan

The brilliant pop hooks and enigmatic lyrics that Donald Fagen and Walter Becker came up with on Steely Dan’s 1972 debut, “Can’t Buy a Thrill,” took the world by surprise and kicked off an epic run of seven LPs that stand as the most ingenious music of the Seventies. By the time of 1977’s “Aja,” Steely Dan had evolved into the Fagen-Becker axis backed by several dozen studio guitarists, saxophonists, pianists and drummers. In 1973, though, it was still a band, and on the criminally underrated “Countdown to Ecstasy,” they were given the chance to stretch out on longer tracks and played with heart and raw talent. In particular, guitarists Denny Dias and Jeff “Skunk” Baxter contributed some sizzling solos and fills on the bluesy “Bodhisattva” and the jazz-inflected “Your Gold Teeth,” and one of the best horn charts ever heard in a pop song carries the exuberant “My Old School.” Meanwhile, the songwriting is wickedly great, from the scathing takedown of the L.A. scene in “Show Biz Kids” and the apocalyptic “King of the World” to the winsome ode to a New Orleans hooker in “Pearl of the Quarter.” What an album!

“Quadrophenia,” The Who

In the beginning, The Who fancied themselves a singles band, pumping out hits like “Substitute,” “My Generation,” “The Kids Are Alright” and “Magic Bus.” Then came their rock opera “Tommy,” and from then on, for Pete Townshend especially, it was more about albums and conceptual art. He nearly drove himself crazy trying to realize his vision of a “one pure note” stage show and film called “Lifehouse,” but he ultimately abandoned it and instead released the best tracks as “Who’s Next,” which many consider The Who’s finest album. For their next project, Townshend looked back at the early days of the band and its audience of “Mods” (modernists), creating a character called Jimmy who, riddled with disillusionment, anger, depression and self-loathing, had four personalities (hence, “quadrophenia”). This inspired Townshend to write some of his best songs (“The Real Me,” “5:15,” “Doctor Jimmy,” “Love Reign O’er Me”), and the group, especially singer Roger Daltrey, responded with incredible performances in the studio. “Quadrophenia” is probably the last superb Who LP, reaching #2 in the US in the fall of 1973.

“The Smoker You Drink, The Player You Get,” Joe Walsh

In 1969, I became a devotee of Joe Walsh because of his phenomenal guitar playing and songwriting as de facto leader of Cleveland’s The James Gang. Do yourself a favor and dive into that band’s brilliant debut “Yer Album,” which made Pete Townshend publicly declare Walsh as the hottest new talent in rock. Walsh stuck around for two more laps (“Rides Again” and “Thirds”) before heading out on his own in 1972. He rounded up some talented backup musicians and called the band (and the first album) “Barnstorm,” a hit-or-miss collection that set the stage for his 1973 major breakthrough, the hilariously titled “The Smoker You Drink, The Player You Get.” Walsh is operating at his peak here, dabbling in rock, blues, folk, jazz, even Caribbean genres, all with frisky fun and undeniable enthusiasm. I’m partial to the piano-driven instrumental “Midnight Moodies,” the languid guitar and vocals of “Wolf” and “Dreams” and the pile-driver rock of “Meadows,” while rock radio put the whimsical “Rocky Mountain Way” in heavy rotation. It’s a gorgeously produced record that still sounds fresh today.

“Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,” Elton John

From the moment I heard “Your Song,” I became a passionate Elton John fan…for a while. The “Elton John” and “Tumbleweed Connection” albums, plus his soundtrack to the French film “Friends,” were in constant rotation on my turntable in 1971, as was “Madman Across the Water” in 1972. Since I preferred his melodic stuff so much, I was a bit put off by the emphasis on upbeat funky pop on “Honky Chateau” and “Don’t Shoot Me, I’m Only the Piano Player,” but in August 1973, he found the right chemistry for his magnum opus, “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road,” which offered 20 songs that struck a balance between upbeat and ballads. The high drama of the synthesized “Funeral For a Friend/Love Lies Bleeding” was an electrifying opener, followed by song after song that used the cinema as literal or metaphorical backdrop (“Candle in the Wind,” “I’ve Seen That Movie Too,” “Roy Rogers” and especially the stunning title song). The album sat at #1 in the US for eight weeks, and as far as I was concerned, it was the last Elton John album I bought for a long time…

“Desperado,” The Eagles

I think the reason I like this album so much is because it was largely overlooked, both at the time of its release and in the years since. Let’s face it, The Eagles catalog is easily the most annoyingly overplayed batch of tunes on rock radio, to the point where I change the channel whenever I hear them. (As Jeff Bridges’ character The Dude says to the cab driver in “The Big Lebowski”: “Come on, I’ve had a rough night, and I hate the fuckin’ Eagles, man!”) But “Desperado” … I don’t know, it’s just so charming and melodic, and its cowboy-outlaw theme holds together surprisingly well. And except for “Tequila Sunrise,” you don’t hear these songs on the radio much. Well, maybe “Desperado” too, but damn, that’s one fine tune. The country influence of original Eagle Bernie Leadon is everywhere here, particularly on “Bitter Creek” and the banjo on “Twenty-One.” The egos of Don Henley and Glenn Frey hadn’t yet ballooned into the realm of insufferable, which allowed their great voices and budding songwriting talents to shine through.

“The Wild, The Innocent and The E St Shuffle,” Bruce Springsteen & The E Street Band

It’s not surprising I didn’t find out about this breathtaking album upon its release in November 1973. Columbia Records did virtually nothing to promote it, due in part to the departure of John Hammond and Clive Davis, who had signed Springsteen in the first place. I became aware of the artist and this album in June 1975 when a friend returned from college on the East Coast (where Springsteen had a following), raving about one song in particular, the exhilarating “Rosalita (Come Out Tonight).” I was so pumped by what I heard that I ran out and bought “The Wild, the Innocent and The E Street Shuffle” the next day. What a seismic, glorious masterpiece of an album! The exuberance of “Kitty’s Back” rivaled “Rosalita”; “Incident on 57th Street” and “New York City Serenade” were stunning vignettes that showed an almost operatic sweep, and “4th of July, Asbury Park (Sandy)” captured my heart with its tale of love and lust on the New Jersey boardwalks. I was lucky enough to see him in concert that summer just before the “Born to Run” album dropped, when he was still hungry and desperate to be heard and embraced. I was hooked.

“A Passion Play,” Jethro Tull

Okay, I admit it. This album is not for everyone. Indeed, Tull is not for everyone. Frontman Ian Anderson is an extraordinary composer, flautist and showman, and you need look only at the band’s “Aqualung” and “Thick as a Brick” LPs or attend a Tull concert for clear evidence of that. But some people haven’t the patience to absorb a 45-minute piece of music like “Brick,” so when the band repeated the feat with the even more challenging “A Passion Play” in 1973, he was requiring a lot of his audience, who were somewhat polarized by the dense subject matter (heaven/hell/afterlife). Me? I totally immersed myself in it, listening to it daily for months on end, captivated by tight ensemble playing, thrilling flute passages and some of Anderson’s finest vocals. Incredibly, it reached #1 on the US Top Albums chart, but critics were merciless, calling it self-indulgent and impenetrable. True, there are some jarring segues between some segments, and he dabbles with soprano sax more than I’d like, but in the final analysis, I think it’s a remarkable LP and a welcome addition to Tull’s impressive catalog.

“Houses of the Holy,” Led Zeppelin

How do you follow up what many feel is the greatest rock album of all time? Led Zeppelin’s fourth record — officially released in 1971 without a title but known alternately as “Untitled,” “Zoso,” “Runes” or “Led Zeppelin IV” — is still rocking the world of each new generation since. “Stairway to Heaven,” “Black Dog,” “Going to California,” “The Battle of Evermore,” “When the Levee Breaks,” “Rock and Roll” — it reads like a greatest hits album, for crying out loud. Finally, in the spring of ’73 came “Houses of the Holy,” which, according to critics, was “artistically sophisticated and cloyingly juvenile.” That’s true in places, but it’s a damn fine album anyway. “D’yer Maker” and “The Crunge” are subpar Zep, but dig Jimmy Page’s guitar shadings on the delicate “The Rain Song” and the marvelous acoustic/electric “Over the Hills and Far Away,” John Paul Jones keyboard-dominant “No Quarter” and John Bonham’s stomping finale, “The Ocean.” Robert Plant’s vocals sound a bit tinny compared to previous outings, but playing the album now takes us right back to 1973 which, in rock music history, was a watershed time.

********************

Here are many honorable mentions:

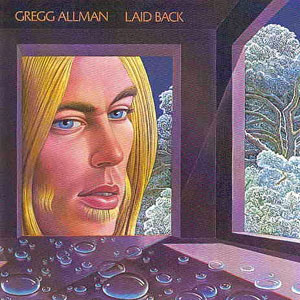

“Laid Back,” Gregg Allman

“Aladdin Sane,” David Bowie

“The Marshall Tucker Band,” The Marshall Tucker Band

“Mystery to Me,” Fleetwood Mac

“It’s Like You Never Left,” Dave Mason

“Let’s Get It On,” Marvin Gaye

“Abandoned Luncheonette,” Hall and Oates

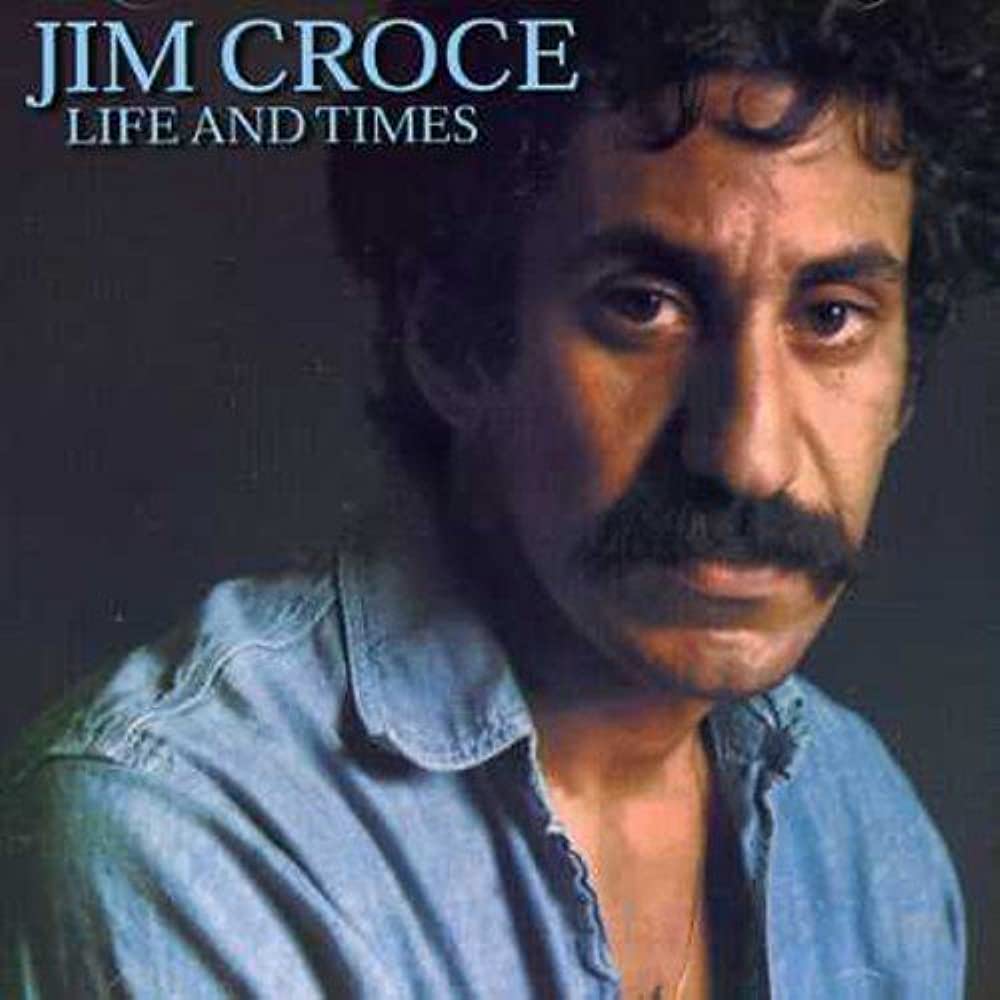

“Life and Times,” Jim Croce

“Selling England By the Pound,” Genesis

“For Everyman,” Jackson Browne

“Brain Salad Surgery,” Emerson, Lake and Palmer

“Pronounced Lehnerd Skinnerd,” Lynyrd Skynyrd

“Diamond Girl,” Seals and Crofts

“Frampton’s Camel,” Peter Frampton

“Foreigner,” Cat Stevens

“Friends and Legends,” Michael Stanley

“Dixie Chicken,” Little Feat

“Don’t Shoot Me, I’m Only the Piano Player,” Elton John

“Closing Time,” Tom Waits

“Over-Nite Sensation,” Frank Zappa

“Ringo,” Ringo Starr

“Bloodshot,” J. Geils Band

“A White Sport Coat and a Pink Crustacean,” Jimmy Buffett

“A Wizard, A True Star,” Todd Rundgren

“A Fool’s Paradise,” Lazarus

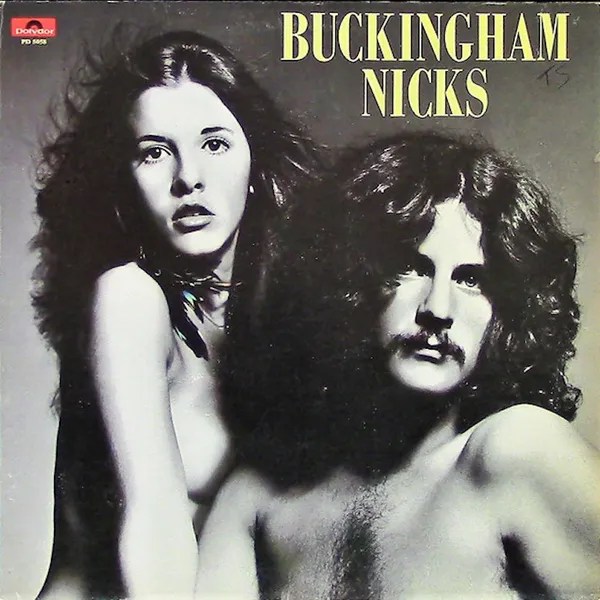

“Buckingham Nicks,” Lindsay Buckingham and Stevie Nicks

**********************