I see sparks fly whenever you smile

“If you smile at me, I will understand, ’cause that is something everybody everywhere does in the same language.” — David Crosby and Stephen Stills, 1969

Unbeknownst to me, last Friday the world celebrated World Smile Day, a day first earmarked in 1999 to encourage “random acts of kindness” designed to bring smiles to people’s faces. So I’m a week late, but I was inspired to examine how songwriters have addressed the act of smiling.

Studies have shown several interesting things about the act of smiling: It lowers your blood pressure, relieves stress, boosts your immune system and improves your mood. Did you know it takes three times as many facial muscles to frown as it does to smile? Here’s a tip: If you wake up “on the wrong side of the bed,” try to muster a smile before your feet hit the floor. It just might turn your day in a more positive direction.

In these strange and difficult times, we could all try to smile a little more and make the world a happier place. If someone smiles at you, try to make a point of smiling back. Sadly, sometimes a smile can be insincere, hiding a deceitful agenda, but typically, a smile serves as a warm greeting or an act of encouragement. In the 15 songs about smiling I’ve collected here (plus a few honorable mentions), only two warn of ulterior motives.

After reading this piece and enjoying the tunes on the accompanying Spotify songlist, I urge you to head on out today and brighten someone’s day with a sincere smile, a random act of kindness, maybe a clever joke. It can’t hurt…

***************************

“Your Smiling Face,” James Taylor, 1977

This joyous uptempo tune was considered something of a departure for Taylor, whose songs tended to be more reflective and melancholy. Most people interpreted “Your Smiling Face” as a love song for his then-wife Carly Simon, with lyrics like “Isn’t it amazing a man like me can feel this way? Tell me, how much longer we can grow stronger every day?” Actually, though, Taylor wrote it about their three-year-old daughter Sally. Critics called it “his most unabashedly happy song ever,” and I’m inclined to agree. It reached #20 on US pop charts in 1977 as the second single from his “JT” album that year.

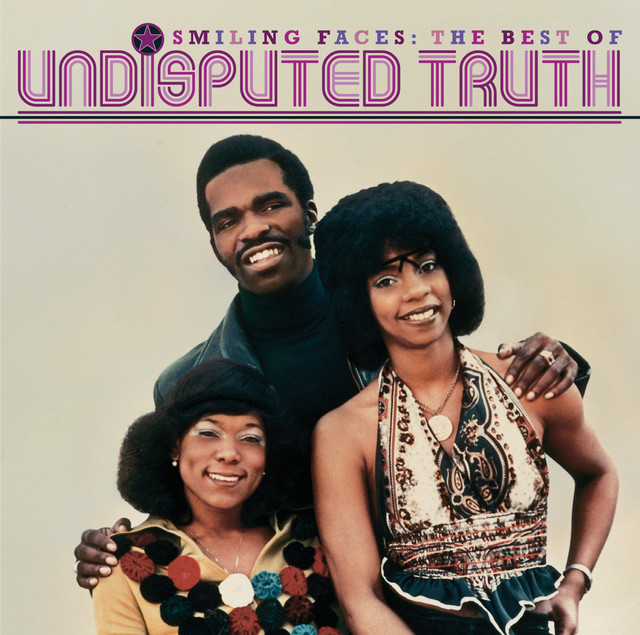

“Smiling Faces Sometimes,” The Undisputed Truth, 1971

The Motown songwriting team of Norman Whitfield and Barrett Strong, responsible for many Temptations hits like “Ain’t Too Proud Beg,” “Cloud Nine,” “I Can’t Get Next to You” and “Papa Was a Rolling Stone,” came up with the compelling “Smiling Faces Sometimes” for the group. They recorded a 10-minute version and intended to edit it down to three minutes for release as a single, but instead, Whitfield also had a new Motown group, The Undisputed Truth, give it a shot, and their version reached #3 on US pop charts in the summer of 1971. It’s a cautionary tale about not always trusting the smile, the handshake and the pat on the back from dishonest types: “The truth is in the eyes ’cause the eyes don’t lie, amen, /Remember, a smile is just a frown turned upside down, my friend, /So hear me when I’m saying, /Smiling faces, smiling faces, sometimes, yeah, they don’t tell the truth…”

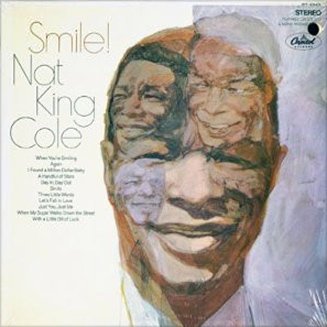

“Smile,” Nat King Cole, 1954

The great comic actor Charlie Chaplin actually teamed up with famed film score producer David Raksin in 1936 to write the music for the piano and violin instrumental piece known as “Smile,” used in perhaps his most famous film “Modern Times.” Nearly twenty years later, lyricists John Turner and Geoffrey Parsons put a full set of words to the music, and Nat King Cole became the first to record it that same year: “If you smile through your fear and sorrow, /Smile and maybe tomorrow, /You’ll see the sun come shining through for you…” It reached #10 in 1954, and since then, it’s been one of the most covered tunes in pop history, recorded by everyone from Judy Garland to Lady Gaga, Barbra Streisand to Eric Clapton, Michael Jackson to Elvis Costello.

“Catch Me Smilin’,” Bill Hughes, 1979

If you’ve never heard the beautiful music this guy created, you’re in for a treat. In 1971, Hughes was the chief songwriter and singer for the Texas-based trio Lazarus, who, under the tutelage of Peter Yarrow, released two gorgeous, harmony-rich albums and toured behind Todd Rundgren but never found the audience that would sustain them. In 1979, Hughes struck out on his own with “Dream Master,” a worthy successor to the Lazarus oeuvre, but it too failed to make much of a dent. Such a shame — just listen to “Catch Me Smilin’,” one of the better tracks on what should’ve been a hit album.

“Your Painted Smile,” Bryan Ferry, 1993

In the ’70s, Ferry helped steer Roxy Music from its rather dissonant art rock beginnings toward a more polished sound for its final albums “Flesh and Blood” and “Avalon.” Ferry’s solo career has expanded on that vibe, with cool, moody music that is more sophisticated than commercial. “Boys and Girls” (1985), “Bête Noire” (1987) and “Mamouna” (1993) managed only modest chart success but included some of his smoothest material, like “Slave to Love,” “Don’t Stop the Dance,” “Kiss and Tell” and, notably, “Your Painted Smile,” which focuses on obsessive romance: “We never close, babe, we dance all night, I’m lost inside, babe, your painted smile…”

“Sara Smile,” Hall and Oates, 1975

In the early ’70s, this Philadelphia-based duo released three R&B-flavored LPs that attracted only a modest following, but their fourth, entitled simply “Daryl Hall + John Oates,” went Top 20 on album charts, thanks to the success of their breakout single, “Sara Smile” (#4 in 1976). Written about Hall’s longtime girlfriend Sara Allen, the tune was decidedly mellower than the many hits for which the duo became known: “When I feel cold, you warm me, /And when I feel I can’t go on, you come and hold me, It’s you and me forever, /Sara, smile…” Hall and Oates became the most successful duo in rock history with 16 Top 10 hits between 1976-1988, including “She’s Gone,” “Maneater,” “Kiss On My List,” “I Can’t Go For That” and “Rich Girl.”

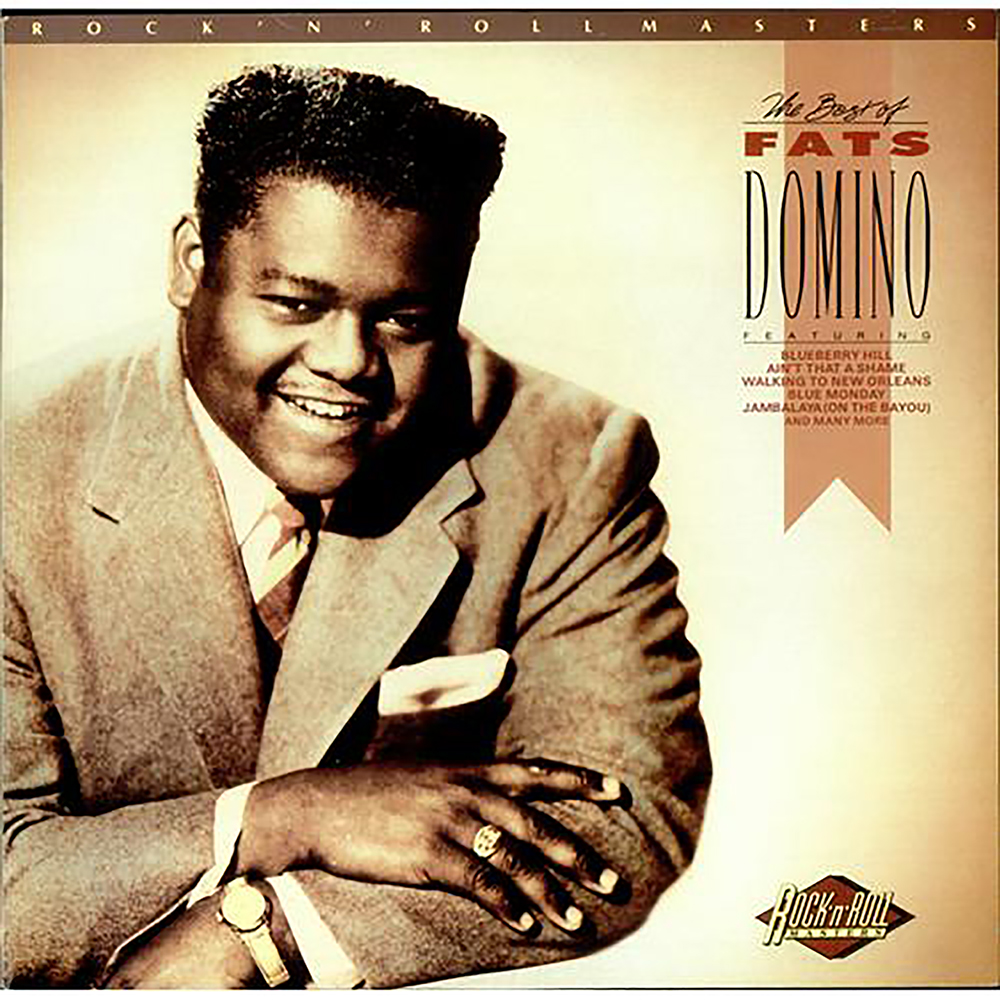

“When You’re Smilin’,” Fats Domino, 1971

This standard is coming up on its 100th birthday, having been written in 1928 and first recorded by a young Louis Armstrong in 1929. Over the decades since, “When You’re Smilin'” has been covered by dozens of artists, from Dean Martin and Billie Holiday to Father John Misty and Michael Bublé. Perhaps the most soulful rendition was recorded by R&B legend Fats Domino in 1971 for his “Fats” album. At that point, Domino was past his prime recording period (1955-1965) but he still had the piano chops and the vocal pipes to pull off a convincing version: “When you’re cryin’, you bring on the rain, /So stop your sighin’, be happy again, /Keep on smilin’, ’cause when you’re smilin’, The whole world smiles with you…”

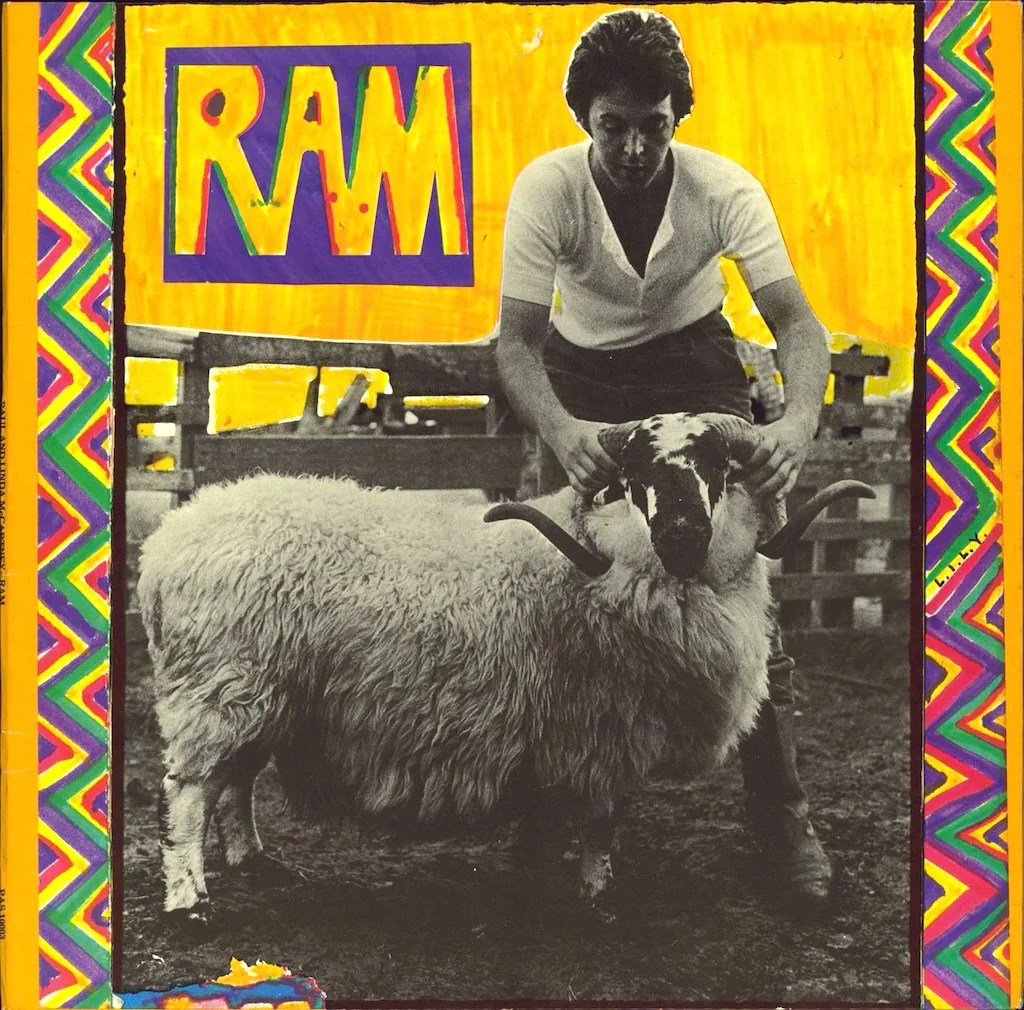

“Smile Away,” Paul McCartney, 1971

Funny how time changes people’s perceptions. An album like McCartney’s “Ram” (1971) that was vilified by critics upon release is now considered one of his two or three best LPs. “The Back Seat of My Car,” “Too Many People,” “Long Haired Lady,” “Dear Boy,” “Heart of the Country” and the #1 hit “Uncle Albert/Admiral Halsey” are all quality McCartney tunes with stellar production. Hidden at the end of Side One is this rough-edged rocker with lyrics stressing the importance of smiling through adversity: “I was walking down the street the other day, oh, who did I meet? /I met a friend of mine and he did say, ‘Man, I can smell your breath a mile away,’ /Smile away, smile away, (learning how to do that)…”

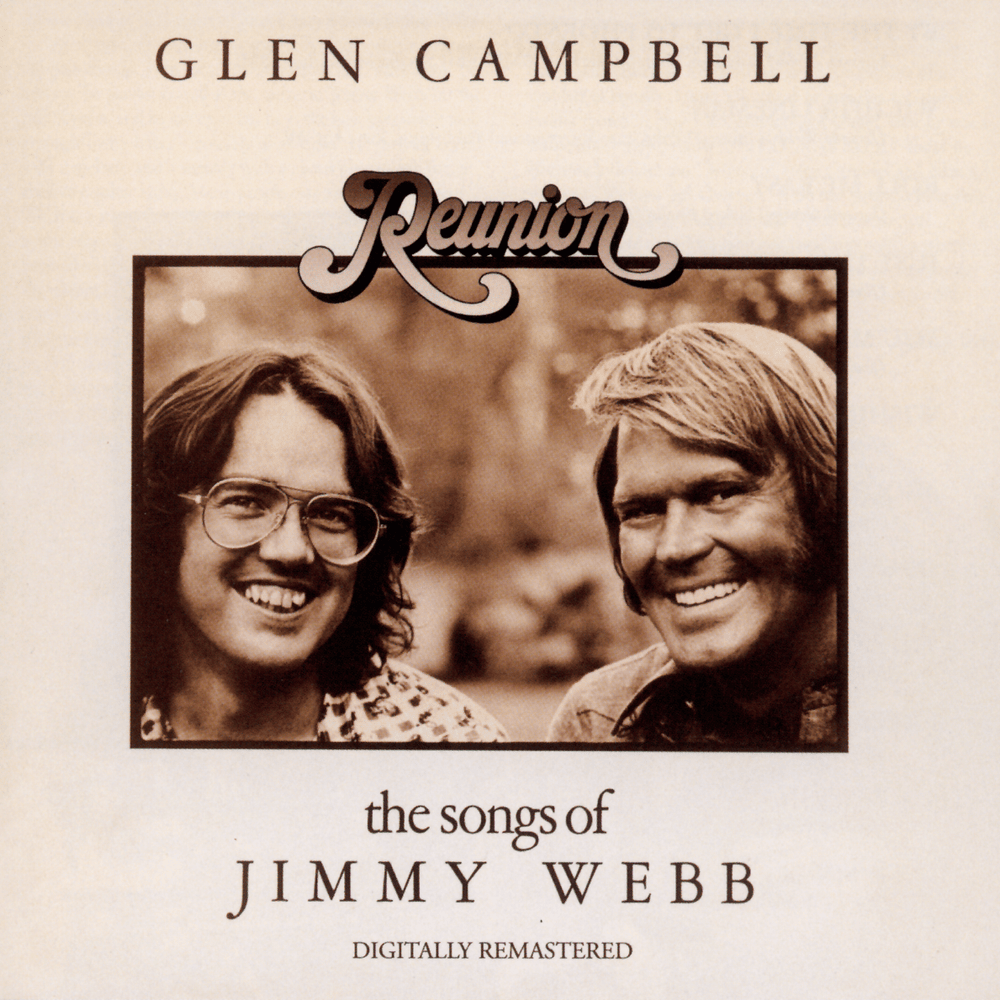

“You Might As Well Smile,” Glen Campbell, 1974

One of the most celebrated pop songwriters of the ’60s and ’70s was Jimmy Webb, who won Grammys writing hits for Campbell, The 5th Dimension, Linda Ronstadt, Carly Simon and Art Garfunkel. Following the success of “By the Time I Get to Phoenix,” “Wichita Lineman” and “Galveston,” Webb continued writing for Campbell, coming up with the heartbreaker “You Might As Well Smile” in 1974. Four years later, Garfunkel also recorded it under the new title “Shine It On Me,” which seemed more hopeful, but the lyrics remain focused on the end of a love affair: “You’re still the best person I ever knew, There were a thousand little things that I was always just about to say to you, /But now the time, it grows shorter…”

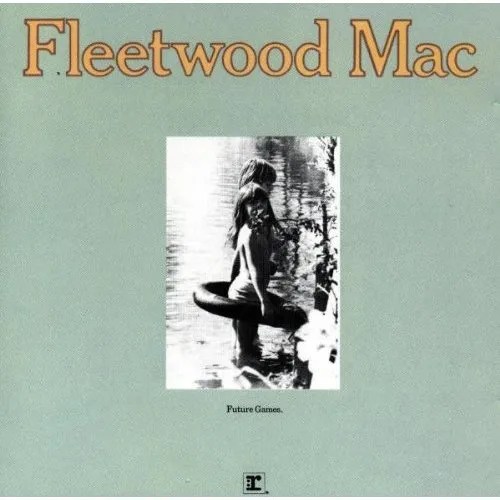

“Show Me a Smile,” Fleetwood Mac, 1971

After the departure of founder/guitarist Peter Green and second guitarist Jeremy Spencer in 1970, Fleetwood Mac regrouped with guitarist/singer Danny Kirwan, guitarist/singer Bob Welch and John McVie’s wife Christine Perfect on keyboards and vocals. Lady McVie made her first songwriting contributions to the band’s repertoire on their “Future Games” LP with “Show Me a Smile” and “Morning Rain,” both of which featured her plaintive voice. “My little child, shine me a light from your eyes, dear, /Don’t let me see a single tear, /Take everything easy, show me a smile…” These tracks set the stage for her to become the band’s most prolific hitmaker a few years later (“Over My Head,” “Say You Love Me,” “You Make Loving Fun,” “Don’t Stop”).

“Smiling Phases,” Blood, Sweat & Tears, 1969

In Traffic’s earliest days, Steve Winwood collaborated with Jim Capaldi and Chris Wood to write most of the material for their debut LP in 1968. “Smiling Phases,” a piece that warns smiling might not always be sincere, was left off the original British release but included in the US version. It consequently didn’t gain much traction until Blood, Sweat and Tears chose to cover it in a markedly different horns-laden arrangement on their stupendous self-titled 1969 album: “Do yourself a favor, wake up to your mind, /Life is what you make it, you see but still you’re blind, /Get yourself together, give before you take, /You’ll find out the hard way, soon you’re going to break, /Smiling phases, going places, /Even when they bust you, keep on smiling through and through…”

“Illegal Smile,” John Prine, 1971

Prine, widely cited as one of the premier songwriters of his generation, turned a lot of heads with his 1971 debut album, which included such classics as “Hello In There,” “Angel From Montgomery” and “Paradise.” The opening track, “Illegal Smile,” was somewhat notorious for what many felt was a veiled reference to marijuana, but as Prine later explained, “It really was not about smokin’ dope. It was more about how, ever since I was a child, I had this view of the world where I found myself smiling at stuff nobody else was smiling at. But it became such a good anthem for dope smokers that I didn’t want to stop every time I played it and make a disclaimer.” “Fortunately, I have the key to escape reality, /And you may see me tonight with an illegal smile, /It don’t cost very much, but it lasts a long while…”

“I Love It When You Smile,” UB40, 1997

This popular British reggae band has been around since 1979, releasing 20 albums in 45 years, a dozen of which were Top Ten on UK charts. Three UB40 albums in the ’80s and ’90s reached the US Top 30, and a pair of singles — reggae remakes of “Red Red Wine” and “I Got You Babe” — were big hits here. On their 1997 LP “Guns in the Ghetto,” there’s a charming track of love and devotion called “I Love It When You Smile” that I’ve always liked: “I love it when you smile when you’re with me, honey, /It happens all the while, how it kills me when you cry…”

“The Shadow of Your Smile,” Glenn Frey, 2012

Written in 1965 by Johnny Mandel and Paul Webster for the Elizabeth Taylor-Richard Burton film “The Sandpiper,” this wistful classic won the Song of the Year Grammy and the Best Original Song Oscar that year. It was covered by more than 30 artists in just the first two years, and well over 100 artists in the decades since, ranging from Barbra Streisand and Tony Bennett to Wes Montgomery and Earl Klugh to Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye. In 2012, Glenn Frey took time out from The Eagles to record an album of standards, and this cover was one of the highlights: “Now when I remember spring, all the joy that love can bring, /I will be remembering the shadow of your smile…”

“Make Me Smile/Now More Than Ever,” Chicago, 1970

The band originally known as Chicago Transit Authority was widely praised for the debut LP in 1969, but its singles failed to ignite much chart success. That all changed the following year when the “Chicago” album (now known as “Chicago II”) came out with the exuberant hit “Make Me Smile,” which reached #9 and put them on the map. “I’m so happy that you love me, /Life is lovely when you’re near me, /Tell me you will stay, make me smile…” It was part of a 13-minute suite called “Ballet For a Girl in Buchannon” that also included the slow-dance favorite “Colour My World.” “Make Me Smile” was later released as and expanded version which includes “Now More Than Ever,” the brief reprise of the main tune that serves as the suite’s final section.

**********************

Honorable mention:

“Smile,” Pearl Jam, 1996; “God Put a Smile on Your Face,” Coldplay, 2002; “Why Don’t You Smile,” The All Night Workers, 1965; “Keep On Smiling,” Wet Willie, 1974; “The Smile Has Left Your Eyes,” Asia, 1983; “When I See You Smile,” Bad English, 1989; “A Wink and a Smile,” Harry Connick Jr., 1993; “Smile a Little Smile For Me,” The Flying Machine, 1969; “When the Lady Smiles,” Golden Earring, 1984; “She Made Me Smile,” Batdorf and Rodney, 1975; “Whatever Happened to Your Smile,” Poco, 1974; “Smile Like You Mean It,” 2004.

**************************