Well, that one went by in a flash

When rock and roll arrived in the 1950s, the music may have pushed a lot of boundaries — the beat, the arrangement, the singing –but not the song length. Virtually every track on every album lasted somewhere between two and three minutes because that’s what radio stations demanded, and record companies eager for airplay were happy to comply.

In the ’60s, though, that began to change. In 1965, Dylan’s iconic hit single “Like a Rolling Stone” broke the six-minute barrier, and The Beatles’ “Hey Jude” in 1968 was more than seven minutes (although some stations cut off the “na na na na-na-na-na” coda well before the end). By the early 1970s, psychedelic groups such as The Grateful Dead and Iron Butterfly and progressive rock bands like Genesis and Jethro Tull were releasing songs that lasted the length of an entire album side — 15 or 20 minutes or more.

But what about the other extreme? I was listening to some vintage albums recently and came across quite a few tracks that pushed boundaries in the opposite direction — songs that last well under two minutes. Some were less than a minute long. It begs the question: Are these really songs, or just song fragments tacked on to albums in a moment of what-the-hell whimsy?

Some short tracks were designed to be brief. James Taylor’s 1972 LP “One Man Dog” has eight tracks clocking in under two minutes. Several were strung together in a six-song medley that concludes the album, but songs like “New Tune,” “Fool for You” and “Chili Dog” are stand-alone tunes that make their case in about 1:40 apiece.

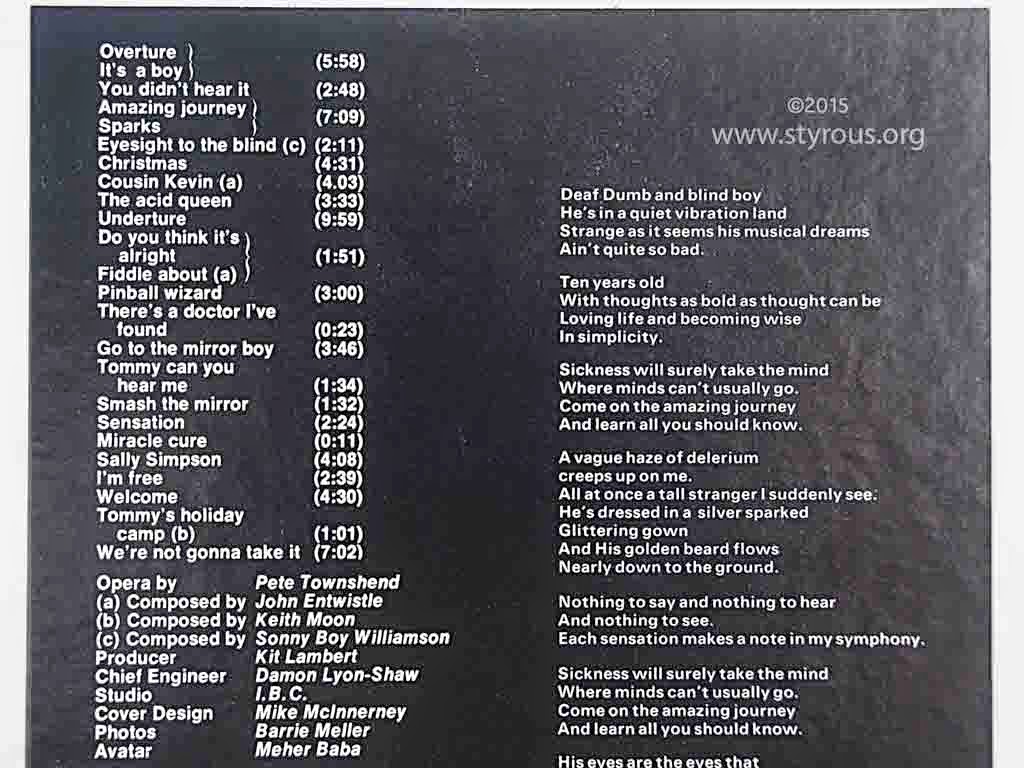

On epic productions like The Who’s “Tommy” or Pink Floyd’s “The Wall,” there are several very short “songs” that are really nothing more than bridges to further the story and connect the longer songs.

Still others sound like they’re unfinished, maybe because the artist lost interest in developing the idea any further, but went ahead and included it on the album anyway. Paul McCartney’s 1970 album opener “The Lovely Linda” (44 seconds) and Taylor’s 1971 album closer “Isn’t It Nice to Be Home Again” (55 seconds) end barely before they’ve begun.

I’ve gathered 21 short-but-sweet examples of brutally concise songs by artists of the ’50s, ’60s, ’70s and ’80s. It certainly won’t take much time to listen to the Spotify playlist found at the end!

********************

“Mercedes Benz,” Janis Joplin, 1971

Joplin had heard a poem by San Francisco beat poet Michael McClure that began, “Come on, God, and buy me a Mercedes Benz.” She began singing that line one night while sitting in a bar with singer-songwriter Bob Neuwirth, and the two of them exchanged verses about other things she might want God to buy for her. This anti-consumerism tune, sung in an a cappella arrangement lasting a mere 1:47, was the last song Joplin ever recorded, and ended up on her posthumous #1 album “Pearl” in 1971.

“Welcome to the Working Week,” Elvis Costello, 1977

The first song on Costello’s astonishing debut LP “My Aim is True” is this 1:23 quickie that immediately establishes him as the fiery non-conformist that would be a defining feature of his career. While classics like “Alison” and “Watching the Detectives” deservedly got more airplay, “Welcome to the Working Week” deftly and succinctly commiserates with working stiffs who head off to a job they hate: “Oh I know it don’t thrill you, I hope it don’t kill you… You gotta do it ’til you’re through it, so you better get to it…”

“Little Deuce Coupe,” The Beach Boys, 1963

While the first three Beach Boys LPs were heavy on surfing tunes, their fourth focused on cars and hot rods, the other key element of the Southern California lifestyle. All the Beach Boys’ early songs were relatively short and to the point (under 2:30 in length), but “Little Deuce Coupe,” which reached #15 as the B-side of the “Surfer Girl” single, faded out at only 1:41. Brian Wilson wrote this and several other car songs with local DJ Roger Christian, who came up with the lyrics. Wilson noted the tune had “a good shuffle rhythm that had a bouncy feel to it.”

“Father of Night,” Bob Dylan, 1970

Out of the 360 songs Dylan has written and recorded on nearly 40 studio albums, this is the shortest. He wrote it and two others for a play by poet Archibald MacLeish entitled “Scratch,” but a disagreement with the play’s producer resulted in Dylan pulling the songs from the project and re-directing them to his next studio album, 1970’s “New Morning.” He wrote “Father of Night” as a modern re-interpretation of Amidah, the central prayer of the Jewish liturgy that encompasses a number of daily blessings.

“Breaking Glass,” David Bowie, 1977

Bowie was fighting cocaine addiction when he fled L.A. in the mid-’70s for Berlin, where he teamed up with ambient music guru Brian Eno. The experimental tracks recorded for Bowie’s “Low” album emphasize tone and atmosphere rather than guitar-based rock, and the music is influenced by German bands such as Tangerine Dream and Kraftwerk. “Breaking Glass” is defined by Bowie producer Tony Visconti as a song fragment (1:52) that was intended to be incorporated into something larger, but was ultimately left as is.

“Oh Baby, Don’t You Loose Your Lip on Me,” James Taylor, 1970

After an unsuccessful debut LP on Apple Records in 1969, Taylor and manager-producer Peter Asher jumped ship from London to L.A. and came up with the simple, direct, unassuming “Sweet Baby James” album, combining acoustic folk, country blues and a smidgen of rock. Nestled next to hits like “Fire and Rain,” “Country Road” and “Steamroller” is this short (1:49) track which features Taylor and longtime collaborator Danny Kortchmar exchanging impressive acoustic guitar riffs while JT puts on a clinic in ad-libbed blues vocals. It’s short and to the point, and a tad messy, but that’s part of its charm.

“Through With Buzz,” Steely Dan, 1974

On “Pretzel Logic,” the group’s third album, songwriters Donald Fagen and Walter Becker came up with some of their catchiest pop tunes (“Night By Night,” “Barrytown,” “Charlie Freak,” “With a Gun”), seemingly determined to bring them in at under three minutes. The shortest of the bunch (1:32) is a curiously appealing number called “Through With Buzz,” a diatribe against a guy who stole the narrator’s money and girlfriend. Fagen has said he got stuck on the song’s structure, unsure where to go next, and chose to abruptly bring it to an end.

“Tea For the Tillerman,” Cat Stevens, 1970

Stevens (now Yusef) made his initial splash in the US with this remarkable 1970 album full of engaging melodies and serious lyrics about searching for spiritual meaning in a soulless society. “Wild World” was the hit single, but “Father and Son,” “Longer Boats” and “On the Road to Find Out” eventually made as much or more impact. Serving as the album’s coda is the brief (1:06) title track, featuring Stevens bringing the album full circle to its opener, “Where Do the Children Play,” singing about how “the children play (rather than pray), Oh Lord, how they play and play for that happy day…”

“Rave On,” Buddy Holly, 1958

Co-written and first recorded by Texas singer Sonny West, “Rave On” became a modest hit for Holly in the US when he laid down his own rendition in early 1958. While it didn’t chart as high as “That’ll Be the Day,” “Peggy Sue” and “Oh Boy” here, it was a Top Five hit in the UK. “Rave On” was highly influential, covered by many other artists over the ensuing decades and ranked at #154 on Rolling Stone’s “500 Greatest Songs of All Time.” Nearly all of Holly’s songs in his brief career were compact, but “Rave On” leads the bunch at 1:47.

“April Come She Will,” Simon and Garfunkel, 1966

On the duo’s five studio albums, you’ll find four tracks under two minutes long, including the whimsical “The 59th Street Bridge Song (Feelin’ Groovy)” and the poignant “Song For the Asking,” but I’ve selected the perfectly concise (1:51) story-poem “April Come She Will.” Quite a few of Simon’s early lyrics focus on isolation, angst and death, and “April,” in which a woman arrives in spring and is gone by autumn, is one of them. It later made an appearance alongside “Mrs. Robinson” and others in the 1967 film soundtrack of “The Graduate.”

“Why Don’t We Do It in the Road?” The Beatles, 1968

John Lennon went on record saying he was disappointed Paul McCartney hadn’t asked him to participate in the studio recording of this bawdy blues tune from The Beatles’ “White Album.” There was tension in the band at the time, as Lennon was distracted by new lover Yoko Ono, so McCartney grabbed Ringo to record the drums while he added keyboards and bass, and gave the song an aptly ragged vocal. Paul wrote “Why Don’t We Do It in the Road?” in India one morning after watching two monkeys copulating on an ashram pathway. It lasts only 1:41.

“Till the Morning Comes,” Neil Young, 1970

From Young’s classic “After the Gold Rush” album, this track certainly sounds as if he gave up on it. It’s got a nice piano-based melody and an arrangement that begins to build in instrumentation (bass, drums, French horn) and voices, but then just when you’re looking for another verse, maybe a bridge, a solo, something, it simply fades out at 1:16. I always wondered whether he regards this tune as unfinished business; knowing him, probably not.

“Rachel,” Seals and Crofts, 1974

The multi-tracked vocal harmonies this soft-rock duo committed to vinyl are some of the prettiest of that era, from “Summer Breeze” and “Diamond Girl” to “We May Never Pass This Way Again” and “Hummingbird.” Jimmy Seals sings lead, with Dash Crofts handling the upper register. On their lesser-known LP “Unborn Child,” you’ll find “Rachel,” less than a minute long and sorely in need of further development. But it somehow works as the Side Two opener, with guitar and mandolin and those impeccable harmonies.

“Cheap Day Return,” Jethro Tull, 1971

Critics have labeled Tull’s “Aqualung” a concept album criticizing organized religion, but in fact, only three songs deal with that subject (“My God,” “Hymn 43” and “Wind Up”). The title track and “Locomotive Breath” are classic rock war horses still in heavy rotation, but scattered throughout the album are reflective acoustic pieces that keep listeners on their toes. One is “Cheap Day Return,” a 1:21-long bauble featuring Ian Anderson musing about an incident when the nurse tending to his dying father asked Anderson for an autograph.

“Call on Me,” The Bangles, 1981

Susanna Hoffs joined forces with sisters Debbi and Vikki Peterson to form The Bangs in 1980, recording their first single “Getting Out of Hand,” backed with the quick-and-dirty “Call on Me” (1:34). Turns out another group owned the name The Bangs, so they modified their name to Bangles and went on to great success in the latter ’80s with power pop hits like “Manic Monday,” “Walk Like an Egyptian” and “Eternal Flame.” There’s a New Wave-y feel to the early “Call on Me,” and an almost countryish guitar solo in the middle.

“(Let Me Be Your) Teddy Bear,” Elvis Presley, 1957

Thanks to aggressive promotion by manager “Colonel” Tom Parker, Presley’s singing and acting careers developed simultaneously, and he found himself in a starring role in the frothy film “Loving You” in 1957, only a year after his first #1 hit (“Heartbreak Hotel”). Jerry Lieber and Mike Stoller wrote the movie’s title song, but it was only the B-side for Presley’s next #1 hit, “Teddy Bear,” penned by Kal Mann and Bernie Lowe. Clocking in at only 1:45, it was one of the shortest #1 singles in Billboard history, and hugely popular, holding the #1 spot for seven weeks.

“Eruption,” Van Halen, 1978

When America’s premier rock band of the 1980s first showed up in 1978 with their self-titled debut LP, one of the tracks that had jaws dropping across the country was “Eruption,” a mind-blowing electric guitar workout featuring (who else?) the late great Eddie Van Halen. It was an instrumental and lasted only 1:44, but it remains high on the list of fan favorites and was often part of their concert set list. (Another short VH track, “Spanish Fly,” only 1:02 in length, features virtuoso Eddie on classical guitar.)

“Smash the Mirror,” The Who, 1969

As mentioned earlier, The Who’s iconic rock opera “Tommy” has a few short tracks that serve to move the story along and link longer, more pivotal songs. At only 1:30, “Smash the Mirror” has the beginnings of a proper tune, but it’s soon clear that its purpose is to be the climactic moment when Tommy has a monumental breakthrough to cure his deaf-dumb-and-blindness, and segues next into “Sensation,” when he realizes the impact he has made as a world-class pinball player.

“Please, Please, Please, Can I Get What I Want,” The Smiths, 1985

Although The Smiths were more of a cult favorite in the US, they were enormously popular and influential in their native England. Their jangly indie rock/pop sound and the smartly accessible songs of lyricist/singer Morrissey and guitarist Johnny Marr made their four albums “must haves” throughout the UK and Europe. Early in 1984, “William, It Was Really Nothing” was a #17 single in the UK, and its B-side was the lush “Please, Please, Please, Let Me Get What I Want,” which leaves the listener wanting more when it ends way too soon at 1:52.

“Stay,” Maurice Williams and The Zodiacs, 1960

This irresistible singalong song was written in 1953 by Williams at only 15, immediately after failing to convince his young date not to go home at 10:00 as her father had insisted. It was finally recorded in 1960 by Williams’s band The Zodiacs, and it reached #1 for a week in December of that year. At 1:36, it still holds the record for shortest #1 song ever on the US charts. The song found new life when Jackson Browne included it on his “Running on Empty” LP in 1977, and again in 1987 when The Zodiacs’ version was used in the film “Dirty Dancing.”

“Seasons,” Elton John, 1971

Before stardom found them, Elton John and songwriting partner Bernie Taupin signed a deal to provide several songs for a French film called “Friends,” directed by Lewis Gilbert. It was a box office dud, but the soundtrack did well thanks to Elton’s involvement. The song “Friends” made the Top 40 in the US, and four others are well worth your attention. There’s a beautiful ballad called “Seasons” that appears twice, tied into some Paul Buckmaster orchestral score music. The full reprise of it at the end of the album lasts 1:39.

**********************

Honorable mention as the shortest tune of them all:

“Her Majesty,” The Beatles, 1969

McCartney wrote this irreverent little ditty about the Queen and placed it between “Mean Mr. Mustard” and “Polythene Pam” on the 15-minute medley from Side 2 of “Abbey Road.” Upon hearing an early run-through of the medley, McCartney decided he didn’t like “Her Majesty” after all and told the engineer to cut it. Having been instructed to never throw any Beatles tape away, he spliced the 36-second tune onto the end of the leader tape for the time being. Later, when the whole band listened to the medley, “Her Majesty” came through the speakers as a surprise after 15 seconds of silence. They loved that and left it there.