This one is personal.

As the summer of 1967 approached, I was leaving elementary school and moving on to “junior high” (middle school these days). I was 12. I had been enjoying pop/rock music since at least 1964 and The Beatles’ appearance on “The Ed Sullivan Show,” and was significantly influenced by my big sister, who loved most of the mid-’60s pop and all the great Motown stuff.

But she hadn’t come along for the ride as The Beatles expanded their wings with the inventive material on “Revolver,” so I never heard those tracks (except the dreadful “Yellow Submarine” and the surprising “Eleanor Rigby,” which were radio singles).

I was puzzled and delighted, respectively, by the double A-side single “Strawberry Fields Forever”/”Penny Lane” in February 1967, and wondered what might come next.

So when the landmark LP “Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band” showed up on June 2, 1967, I was dazzled, knocked out, blown away (like the rest of the world, apparently)  as my friend Paul cranked it up on his stereo that fine summer day. My first impression was, wow, there was SO much going on! New instruments, intriguing sound effects, and an insanely broad variety of musical genres, including rock, big band, vaudeville, jazz, blues, chamber music, circus, music hall, avant-garde, Indian…

as my friend Paul cranked it up on his stereo that fine summer day. My first impression was, wow, there was SO much going on! New instruments, intriguing sound effects, and an insanely broad variety of musical genres, including rock, big band, vaudeville, jazz, blues, chamber music, circus, music hall, avant-garde, Indian…

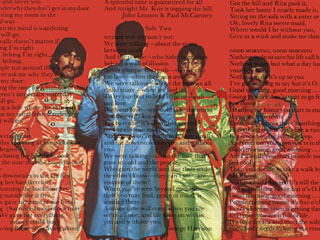

And holy smokes, what an array of truly astounding lyrics — printed on the back of the album for the first time! — lyrics about newspaper taxis and cellophane flowers, Wednesday morning at five o’clock, painting the room in a colorful way, some guy named Billy Shears, 4,000 holes in Blackburn, Lancashire, and a band that’s been going in and out of style.

It was a revelation — so much so that, for the first time, I used my own money to buy my first album a couple of days later.

As Paul McCartney explained, “We were kind of fed up with being Beatles. We had grown to hate that four little mop-top boys approach. We were not boys anymore, we were men. And we weren’t just performers, we were artists.”

Abandoning the unpleasant world of touring, The Beatles turned their attention to the studio, and decided they would make their statement there, creating music that wasn’t  intended to, and couldn’t, be performed live. Producer George Martin explained, “These songs were designed to be studio productions, using new recording techniques and electronic possibilities that gave them the ability to paint sound rather than photograph it. And that was the difference.”

intended to, and couldn’t, be performed live. Producer George Martin explained, “These songs were designed to be studio productions, using new recording techniques and electronic possibilities that gave them the ability to paint sound rather than photograph it. And that was the difference.”

The process started slowly, not fully formed. McCartney had come up with a novel concept that would help downplay the suffocating idolatry that had made their lives miserable. “I got this idea,” he said. “I thought, ‘Let’s not be ourselves. Let’s develop alter egos so we’re not having to project the same old image which we know.’ It would be much more free, an entirely different approach.”

The San Francisco music scene at that time was rife with groups bearing elaborate names like Strawberry Alarm Clock, Big Brother and the Holding Company and Quicksilver Messenger Service, and they thought it would be fun to concoct a name that hearkened back to the Victorian brass bands, bringing a rock and roll sensibility to traditional musical styles. Lennon noted, “These West Coast long-name groups, like Fred and his Incredible Sheep Shrinking Grateful Airplanes, or whatever it might be, inspired us.” And behind this facade would be John, Paul, George and Ringo, doing their thing in a whimsical, mind-blowing way.

To say they succeeded would be a laughable understatement. As Lennon later put it, “We tried and, I think, succeeded in achieving what we set out to do.”

And yet, “Sergeant Pepper” wasn’t truly the “concept album” it was originally conceived to be. It started boldly with McCartney’s muscular title track introducing us to a show by the fictitious “band,” complete with crowd noises, followed by Ringo’s cheerful number, “With a Little Help From My Friends.” But after that, the tracks had little to do with the notion of a fake band playing some other group’s songs. As Lennon put it, “My contributions to the album had nothing whatsoever to do with this idea of Sgt. Pepper and his band. The songs would’ve fit on any other Beatles LP.”

Still, the sheer diversity of the musical styles that followed made the album seem like a virtual variety show, featuring Indian music (George Harrison’s mesmerizing “Within You Without You”), old-fashioned dance hall tunes (“When I’m Sixty- Four”), circus music (“Being For the Benefit of Mr. Kite”), and typical Beatles pop (“Getting Better”).

The effect was almost overwhelming at the time, in large part because its timing was perfect, at the peak of Swinging London and the beginning of the so-called “Summer of Love.” No one — not even The Beatles on “Revolver” — had reconfigured the pop landscape like this before. For a brief period, the music of “Sgt. Pepper” burst forth from every open window, every club, every radio station. It was truly transformational.

Most critics lauded it as “a masterpiece” and “a decisive moment in the history of popular music,” an album that “elevated the pop song to the level of fine art.”

And yet, years later in retrospect, many observers regard these songs as dated, flawed “period pieces” of a long-forgotten time, while the tracks on “Revolver” or their later work (“The White Album” and “Abbey Road”) stand up far better 40 or 50 years later.

Rolling Stone‘s Greil Marcus felt “Sgt. Pepper” was “playful yet contrived” and suggested it was “strangled by its own conceits.” Richard Goldstein of The New York Times wrote, “It’s dazzling but ultimately fraudulent” as studio confection. In his 2011 autobiography, Keith Richards called the album “a mishmash of rubbish, sort of like ‘Satantic Majesties.'”

Even Harrison and Starr went on record as saying they didn’t much care for it. “I found it tiring, and a bit boring,” said George years later. “I had a few moments in there that I enjoyed, but generally, I didn’t like the album much. I preferred ‘Rubber Soul’ and ‘Revolver.'” Ringo added, “The thing I remember about making that album is I learned how to play chess. I spent hours and hours waiting to record my parts while the geniuses worked on the overdubs and little extra frills.”

Obviously, most people thoroughly embraced it, evidenced by its place atop many “Best Albums of All Time” lists over the years. It’s hard to fathom now, but in 1967, this  album seemed to change everything: It made the album the pre-eminent musical format instead of the single; it made the inclusion of printed lyrics a commonplace feature; it made it okay to create music in the studio that wasn’t likely to be recreated live on stage. Said Martin in 2007: “‘Sgt. Pepper’ was a musical fragmentation grenade, exploding with a force that is still being felt. It grabbed the world of pop music by the scruff of the neck, shook it hard, and left it to wander off, dizzy but still wagging its tail.”

album seemed to change everything: It made the album the pre-eminent musical format instead of the single; it made the inclusion of printed lyrics a commonplace feature; it made it okay to create music in the studio that wasn’t likely to be recreated live on stage. Said Martin in 2007: “‘Sgt. Pepper’ was a musical fragmentation grenade, exploding with a force that is still being felt. It grabbed the world of pop music by the scruff of the neck, shook it hard, and left it to wander off, dizzy but still wagging its tail.”

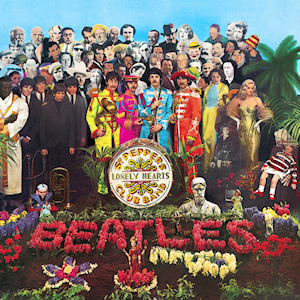

We should talk a bit about the album cover, which was yet another radical departure from what had been seen before. Assembling cardboard cutouts of 50+ celebrities and historical figures, setting them up in rows behind the four lads, who were dressed in shiny, colorful Victorian-era brass-band suits, was a huge undertaking that  made an enormous impact on cover design from then onward. No longer would album covers be designed by lame record-company hacks. It would now be a new canvas on which the younger generation’s artistic upstarts would share their visions.

made an enormous impact on cover design from then onward. No longer would album covers be designed by lame record-company hacks. It would now be a new canvas on which the younger generation’s artistic upstarts would share their visions.

But it’s the music I really want to talk about here. And while I would probably rank “Sgt. Pepper” no higher than fifth on my list of favorite Beatles albums, I was gobsmacked when I listened to the brand-new remixed stereo album released last week, which features the wondrous engineering work of the late George Martin’s son Giles, who went back to the original four-track recordings to produce a proper mix that features all the instruments, voices and effects in all their intended glory. A companion CD offers fascinating “rough drafts” of each song, giving hints as to how the tracks evolved.

It must be mentioned that “Sgt. Pepper” would have been significantly better had it included the first two tracks recorded for it, “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane.” These beauties were the first two songs recorded in November 1966, but EMI Records insisted on releasing them as a double A-side single several months in advance of the LP. Because The Beatles had a tradition of never putting their singles on the subsequent album (at least in Britain), “Strawberry Fields” and “Penny Lane” were omitted. Personally speaking, I’d like to imagine the album with these two extraordinary songs in place of lesser tracks like “When I’m Sixty-Four” and “Good Morning Good Morning.”

It must be mentioned that “Sgt. Pepper” would have been significantly better had it included the first two tracks recorded for it, “Strawberry Fields Forever” and “Penny Lane.” These beauties were the first two songs recorded in November 1966, but EMI Records insisted on releasing them as a double A-side single several months in advance of the LP. Because The Beatles had a tradition of never putting their singles on the subsequent album (at least in Britain), “Strawberry Fields” and “Penny Lane” were omitted. Personally speaking, I’d like to imagine the album with these two extraordinary songs in place of lesser tracks like “When I’m Sixty-Four” and “Good Morning Good Morning.”

Ah well. Let’s take a look at the tunes themselves:

“Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band”/”Sgt. Pepper reprise”

McCartney gets all the credit for these two pieces that frame the idea of the LP being the work of Sgt. Pepper and his band, not The Beatles. Thanks to some blistering electric guitar work by Paul, the opening track and its reprise near the end rock out more than any other songs on the LP.

“With a Little Help From My Friends”

Generally regarded as Ringo’s finest vocal moment in the band’s repertoire, this was the last one written for the album. John and Paul came up with it one evening late during the sessions with Ringo’s vocal in mind, and it fit perfectly as the second number following the “Sgt. Pepper” intro. Most people regard Joe Cocker’s 1969 cover version far superior, but the original is upbeat and fun, in keeping with the album’s overall spirit.

“Lucy in the Sky With Diamonds”

When John’s son Julian presented him with a drawing he’d made in pre-school, John inquired as to what it was. “It’s my friend Lucy, in the sky, with diamonds,” the boy said. Just an innocent way of honoring his young friend…and John took that title and ran with it, coming up with one of most surreal, dreamlike tracks in the pop music canon. Although widely perceived as a paean to, and celebration of, LSD and drug-taking, Lennon has always adamantly denied it. “It’s just a fantasy based on a child’s drawing,” he claimed.

“Getting Better”

“Getting Better”

McCartney could aways be counted on to provide a sunny, bouncy song somewhere in the mix, and “Getting Better” was this album’s example. But the more acerbic, cynical Lennon injected his thoughts with lines like “it can’t get no worse” (sung three times), which he felt balanced out what was otherwise too positive a song. “Life just isn’t that bright for many people,” he believed.

“Fixing a Hole”

Another fine McCartney tune with an infectious melody. It was on this album, with tracks like this one, when Paul began asserting himself more as the band’s de facto musical director, as Lennon gradually withdrew, became more involved in other pursuits.

“She’s Leaving Home”

More so than even “Yesterday” or “Eleanor Rigby,” this track uses classical stringed instruments to marvelous effect as McCartney sings the poignant tale of a teenaged girl running away from home. Lennon’s contribution was to view it from the parents’ viewpoint, selfishly wondering what they’d done wrong. A lovely piece.

“Being for the Benefit of Mr Kite”

“Being for the Benefit of Mr Kite”

Lennon found a vintage poster of an old-time traveling show full of circus-type attractions and used it as the basis for this swirling, chaotic Midway of a track that, although fitting in this album’s context, was criticized as being “about as far from rock and roll as you can get,” noted Lou Reed in 1975.

“Within You Without You”

The placement of Harrison’s droning piece at the beginning of Side Two (remember Side Two?) made it easy for me to skip it when I lowered the needle onto the vinyl back in the ’60s. While I’ve grown to appreciate it, particularly the lyrics, this track is too long by half.

“When I’m Sixty-Four”

An inoffensive example of what Lennon derisively called “that Granny music Paul likes.” Again, it fits within the context of the album, but it’s ultimately pretty inconsequential.

“Lovely Rita”

A joyous track full of rollicking piano and great vocals. This one wouldn’t have sounded out of place on “Revolver” or “The White Album,” in my opinion.

“Good Morning Good Morning”

Lennon dismissed this track years later as “a piece of rubbish,” largely because it was inspired by a TV commercial for corn flakes. But it also served as a springboard for a whole stable of animal noises in the fadeout, leading into the final two tracks.

“A Day in the Life”

How appropriate that this one is saved for the closer. In retrospect, I believe it stands as the very pinnacle of the 215 songs they wrote, and puts a dramatic finale on their most iconic LP. John brought the basic song to the studio, based on a couple of items he’d seen in the newspaper about a friend who’d died in a car accident and a story about potholes in the town of Blackburn. McCartney had a little unfinished ditty about a memory of his  morning routine every school day (“Woke up, fell out of bed”), and they found a crafty way of merging the two into one amazing piece.

morning routine every school day (“Woke up, fell out of bed”), and they found a crafty way of merging the two into one amazing piece.

The transition between the two still stands as the most revolutionary segue ever conceived — a symphony orchestra starting on the same note, gradually moving up at their own pace, getting increasingly louder until they arrived tumultuously at the same note 24 bars later. As McCartney put it: “We needed something really amazing, a total freak-out.” Lennon described it as “a sound building up from nothing to the end of the world.” The result was almost frightening in its intensity, and The Beatles loved the results so much that they repeated it as the song’s denouement, capped with all four Beatles simultaneously hitting the same E chord on pianos, letting the note ring out for 40 seconds to fadeout. Fantastic.

*********

“Sgt. Pepper” has been overanalyzed and researched to death, and is in many ways one of the most overrated albums ever made, if only because of the social/cultural impact that has always been attached to it. It’s clever, daring, pretentious, profound, wildly creative, technically trailblazing and, not incidentally, it’s a whole lot of fun.

Do yourself a favor and listen to it again (the 2017 remix) in its entirety. What an experience!

Terrific!

LikeLike

Dear Hack,

Great review (and remembrance) of a great album. I agree that Pepper wasn’t their best album, in terms of song-writing, but it certainly was their most important in their long-term development as artists (as well as all R&R artists, as well). If their prior work was a fun, easy drive in the pop/rock countryside, with some small hills and gentle curves, then Sgt. Pepper was a sharp left turn, with a steep drop into a whole new ride.

It was the transition from black and white to color when Dorothy opened her house door to Munchkin land; or the first time you watch the opening scene in Star Wars as the Imperial Battle ship engulfs the entire widescreen. The world of rock music had changed for good, and musical artists would need to change to survive.

Among all the stories of the album’s impact on other artists, the Brian Wilson reaction stands out. He had fully poured himself into creating Pet Sounds, in response to the Beatles’ Rubber Soul album. McCartney later stated that he loved Pet Sounds, and thought it was the best album ever produced, but he also acknowledged that Sgt. Pepper was a competitive reply to Wilson. Wilson, reportedly, flipped out after hearing Pepper for the first time — although Wilson so doped up, and emotionally edgy in those days, that he only needed to little push to lose it. Poor guy — he served as song writer, composer, arranger, producer and performer for the Beach Boys — he did the jobs of McCartney, Lennon and George Martin, combined.

Interesting point about A Day in the Life — as you point out, McCartney’s bridge is essentially another song, within the song, with chord and tempo transitions merging the two together. This idea was considerably expanded and evolved by the time they composed side two of Abbey Road; the “Medley” of eight short songs are woven together seamlessly into one masterpiece.

Also, with Sgt. Pepper, there was a new songwriter in The Beatles — LSD. The boys had been doing pot regularly since Dylan lit up their first joint in 1964, but the intense mind-altering impact of lysergic acid diethylamide, and other hallucinogenics — opened up their musical creativeness to whole new, unexplored areas. While perhaps too much drug interpretations have been made of some of the songs — notably Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds — but even McCartney acknowledged, to George Martin of all people, that Sgt. Pepper was a drug album, start to finish.

Could they have done the album straight? Maybe, but that probably means we would have had to listened to it straight. And where’s the fun in that!

My best always,

Duryea

LikeLike

Many thoughtful comments, Phil. I like that bit about “the sharp left turn into a whole new ride.”

Thanks for responding. If you haven’t ponied up for the new stereo mix, I strongly urge you to do so.

LikeLike

Nice balanced analysis Bruce. Thanks for rekindling the moment of mutual discovery so many years ago. A Day in the Life.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I even remember which tracks pushed your buttons the most…

LikeLike