There are those who maintain that rock ‘n’ roll was born in 1955, roughly with the ascension of Bill Haley & The Comets’ “Rock Around the Clock” to #1 on the charts, where it remained for eight weeks throughout July and August that year.

Others point to the emergence of Elvis Presley, whose first single, “That’s All Right,” was released in July 1954. But it stiffed on the charts, and Elvis wouldn’t become a star until “Heartbreak Hotel” in January 1956.

The truth is, both theories are incorrect. Most rock music historians insist that rock ‘n’ roll as a genre — essentially combining jump blues, jazz, boogie woogie, rhythm & blues and country — dates back to the December 1949 release of a rollicking tune called “The Fat Man,” a high-spirited reworking of a 1940 piano blues called “Junkers Blues” by  Champion Jack Dupree. “The Fat Man” reached #2 on the R&B charts and sold a million copies by the end of 1950.

Champion Jack Dupree. “The Fat Man” reached #2 on the R&B charts and sold a million copies by the end of 1950.

And who co-wrote, sang and played piano on this trailblazing song? None other than Antoine “Fats” Domino, a (the?) bonafide pioneer of rock music, who died last week at the ripe age of 89. Sadly, yet another rock hero has joined the amazing band being assembled in rock ‘n’ roll heaven…

Domino was an important member of the fraternity of musicians (Chuck Berry, Jerry Lee Lewis, Little Richard, Buddy Holly and Presley, among others) who brought rock ‘n’ roll into the popular mainstream charts in 1955-1956, with the aforementioned “Rock Around the Clock,” Chuck Berry’s “Maybellene” and Domino’s “Ain’t That a Shame” leading the way. Over the next 18 months, Domino would follow that classic with more piano-driven hits like his signature hit “Blueberry Hill” (Richie Cunningham’s favorite on TV’s “Happy Days”), “I’m Walkin'” and “It’s You I Love.” All of them have become standards from the early rock ‘n’ roll era.

All told, Domino sold upwards of 65 million records in his five-decade career, with 35 hits in the Top 40 (eleven in the Top 10). The fact that he sold more records than any ’50s rock figure except Presley is often overlooked, in part, perhaps, because Domino was inordinately shy and humble, especially compared to most rock ‘n’ roll stars.

Presley, also a humble man back then, knew enough to defer to Domino and his influence. “A lot of people seem to think I started this business,” he told Jet Magazine in 1957. “But rock ‘n’ roll was here a long time before I came along. Nobody can sing that music like colored people. Let’s face it: I can’t sing it like Fats Domino can. I know that.”

He reinforced this message a decade later when, at a 1969 press conference introducing his new single, “Suspicious Minds,” Presley brought Domino to the podium with him, praising him as “a huge influence on me.” When a reporter referred to Presley as “The King,” he interrupted and said, “No, no. This gentleman right here, he’s the real king of rock ‘n’ roll.”

He reinforced this message a decade later when, at a 1969 press conference introducing his new single, “Suspicious Minds,” Presley brought Domino to the podium with him, praising him as “a huge influence on me.” When a reporter referred to Presley as “The King,” he interrupted and said, “No, no. This gentleman right here, he’s the real king of rock ‘n’ roll.”

He stood only 5’5″ and seemed almost as wide as he was tall, with a head shaped like a cube because of his trademark flat-top haircut. He had an infectious grin and a pleasing way about him, delivering his boogie-woogie music seated sideways on his piano stool, turning his head to the audience as he sang.

In 1957, a newsreel reporter asked, “Fats, how did this rock ‘n’ roll all get started anyway?” Domino smiled and replied, “Well, what they call rock ‘n’ roll now is rhythm and blues, and I’ve been playing it in New Orleans for 15 years.”

That’s actually not an exaggeration. Domino, born in New Orleans in 1928 as the youngest of eight children, learned piano from his jazz musician brother-in-law, and found himself at age 14 playing in bars all over the French Quarter and the city’s Lower Ninth Ward, where he lived virtually his entire life.

New Orleans bandleader Billy Diamond gave Domino his first break at age 19 in 1947 by adding him to his lineup, and gave him his “Fats” nickname because of his big appetite. David Bartholomew, the songwriter/producer/arranger who worked with Domino for  much of his recording career, said Fats quickly became the focal point and frontman of that band. “He was singing and playing the piano and carrying on, always smiling from ear to ear,” Bartholomew said. “Everyone was having a good time when Fats was playing. It was like a party.”

much of his recording career, said Fats quickly became the focal point and frontman of that band. “He was singing and playing the piano and carrying on, always smiling from ear to ear,” Bartholomew said. “Everyone was having a good time when Fats was playing. It was like a party.”

Domino signed with Imperial Records in 1949 and embarked on a 15-year relationship that spawned most of his chart success. Following the triumph of “The Fat Man,” he became a regular presence on the R&B charts with both slow and fast tempo tracks: “Every Night About This Time,” “Rockin’ Chair,” “Goin’ Home” (a #1 hit), “Poor Poor Me,” “Going to the River,” “Please Don’t Leave Me,” “Rose Mary,” “Something’s Wrong,” “You Done Me Wrong,” “I Know” and “Don’t You Know,” and all charted in the R&B Top 10 between 1950 and 1954.

Domino was among the more important figures in the effort to break down the musical color barrier by bringing R&B sounds (then termed “race records” by the pop music industry) to white audiences. Thanks to innovative, revolutionary radio DJs like Cleveland’s Alan “Moondog” Freed, who relished the opportunity to play R&B music to his unusually integrated radio audience on the midnight shift, early rock recording artists like Domino received invaluable exposure previously denied to black musicians.

Domino and fellow rock pioneer Little Richard were prime examples of black artists who introduced extraordinary rock recordings which were immediately re-recorded and surpassed on the charts by white artists. In particular, Pat Boone, whose squeaky-clean image made him a favorite in heartland America, made soulless, sanitized cover versions of Domino’s “Ain’t That a Shame” and Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti” and took both into the Top Five, while the originals consequently charted much lower. (Boone even had the audacity to suggest changing the title to the grammatically correct “Isn’t It a Shame” until his producer intervened.) While it’s true that Boone’s safer, more acceptable renditions helped bring the rock ‘n’ roll genre to a broader white audience at the time, they are without question inferior to the vital, energetic originals. (Both versions appear back-to-back on the Spotify list below.)

Domino and fellow rock pioneer Little Richard were prime examples of black artists who introduced extraordinary rock recordings which were immediately re-recorded and surpassed on the charts by white artists. In particular, Pat Boone, whose squeaky-clean image made him a favorite in heartland America, made soulless, sanitized cover versions of Domino’s “Ain’t That a Shame” and Little Richard’s “Tutti Frutti” and took both into the Top Five, while the originals consequently charted much lower. (Boone even had the audacity to suggest changing the title to the grammatically correct “Isn’t It a Shame” until his producer intervened.) While it’s true that Boone’s safer, more acceptable renditions helped bring the rock ‘n’ roll genre to a broader white audience at the time, they are without question inferior to the vital, energetic originals. (Both versions appear back-to-back on the Spotify list below.)

Domino’s recording of “Ain’t That a Shame” still managed to reach #10, and it was followed over the next five years by no less than 10 hits that reached the Top 10 on the mainstream charts, an unprecedented success for a black artist: “I’m in Love Again” (#3), “Blueberry Hill” (#2), “Blue Monday” (#5), “I’m Walkin'” (#4), “Valley of Tears” (#8), “It’s You I Love” (#6), “Whole Lotta Loving” (36), “I Want to Walk You Home” (#8), “Be My Guest” (#8) and “Walking to New Orleans” (#6).

Fats appeared alongside other early rock giants in a couple of rock ‘n’ roll movies Hollywood churned out to capitalize on the new craze, including the lightweight “Shake, Rattle and Rock!” and the more substantial “The Girl Can’t Help It.” Both served to  broaden his reach and build his career momentum, as did his appearance on the influential “Ed Sullivan Show” in 1956.

broaden his reach and build his career momentum, as did his appearance on the influential “Ed Sullivan Show” in 1956.

In 1962, Domino toured Europe for the first time and met the young and struggling Beatles, who lauded him as a major inspiration ever since. The same year, he played his first of many stands in Las Vegas.

But the winds of change were blowing. When Imperial Records was sold in 1963, he jumped ship to ABC-Paramount, who insisted he record in their Nashville studio instead of the New Orleans studio he’d always considered his home base. That move proved ill-advised; he managed only one more Top 40 hit (Red Sails in the Sunset, #35), although he continued making singles and albums for Mercury and then Reprise until about 1970.

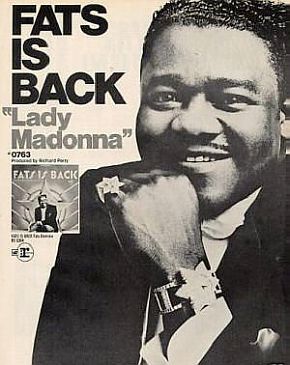

The arrival of the British Invasion bands, folk rock and psychedelic rock in 1964 and beyond represented a monumental shift in public tastes, shunting ’50s pioneers like Domino to the sidelines. Still, Paul McCartney publicly mentioned Domino when he wrote The Beatles’ “Lady Madonna” in 1968. “Basically, I was channeling Fats and his piano-playing style on that one,” he said. Domino then returned the favor by including a vigorous cover of “Lady Madonna” on one of his final albums, “Fats is Back,” as well as a passionate rendition of Lennon’s “White Album” track, “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except For Me and My Monkey.”

The arrival of the British Invasion bands, folk rock and psychedelic rock in 1964 and beyond represented a monumental shift in public tastes, shunting ’50s pioneers like Domino to the sidelines. Still, Paul McCartney publicly mentioned Domino when he wrote The Beatles’ “Lady Madonna” in 1968. “Basically, I was channeling Fats and his piano-playing style on that one,” he said. Domino then returned the favor by including a vigorous cover of “Lady Madonna” on one of his final albums, “Fats is Back,” as well as a passionate rendition of Lennon’s “White Album” track, “Everybody’s Got Something to Hide Except For Me and My Monkey.”

Although Domino retired from the studio, he remained a formidable presence on the road throughout the ’70s and ’80s, touring periodically, making special concert appearances at charity events in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago and elsewhere, and continuing to hold court in Vegas. And let’s not forget the impact he had on the next generation of piano-playing rockers, from Dr. John and Leon Russell to Elton John and Billy Joel. When Lennon chose his favorite early rock songs to record for his “Rock and Roll” LP of covers in 1975, front and center was “Ain’t That a Shame.” Even a band like Cheap Trick took the same song back up the charts in 1978 (#35 in the US, #10 in Canada) with a live version from their “Cheap Trick at Budokan” album.

By the late 1980s, as he reached 60, Domino chose to withdraw from the public eye, preferring to stay home in New Orleans, close to his wife of 40 years, Rosemary, and his eight children. He declined an invitation in 1987 to attend his induction as a member of the charter group of Rock and Roll Hall of Fame honorees.

He mounted one last tour in 1995, playing to enthusiastic crowds in two dozen European cities, but ill health made it an unpleasant experience for him, and he never went on the road again after that.

He mounted one last tour in 1995, playing to enthusiastic crowds in two dozen European cities, but ill health made it an unpleasant experience for him, and he never went on the road again after that.

When Hurricane Katrina hit in 2006, he chose to remain in his home with his ailing wife, and when he hadn’t been heard from in a couple of days, rumors spread that he had perished in the disaster. It turned out the couple had been rescued by a Coast Guard helicopter, but Domino lost “almost everything” in the flood.

His final public performance came the following year at Tipitina’s, a favorite local club in New Orleans, where he was among the celebrities who participated in the post-Katrina  benefit. Also in 2007, Vanguard Records released “Goin’ Home: A Tribute to Fats Domino,” a collection of cover versions of Fats Domino classics by such luminaries as Elton John, Neil Young, Robert Plant, Lucinda Williams, Lenny Kravitz, Norah Jones, Dr. John and Willie Nelson.

benefit. Also in 2007, Vanguard Records released “Goin’ Home: A Tribute to Fats Domino,” a collection of cover versions of Fats Domino classics by such luminaries as Elton John, Neil Young, Robert Plant, Lucinda Williams, Lenny Kravitz, Norah Jones, Dr. John and Willie Nelson.

Domino was revered by musicians and city dignitaries alike. “On behalf of the people of New Orleans, I am eternally grateful for Fats Domino’s life and legacy,” said Mayor Mitch Landrieu last week. “For a city known for its talented musicians, Fats was one of the all-time greats. He added significantly to New Orleans’ standing in the world, and what people know and appreciate about our city.”