Holy Moses, I have been removed

I’ve written before about how music — a certain song, a certain album, a certain artist — has a way of instantly taking you back in time to when you first heard it. Sometimes you can recall exactly where you were, who you were with, what you were doing. And if you hear that song or album today, even 20, 30, 40 years later, a wellspring of emotions and memories comes flooding up.

This can be a bad thing, of course. I’ll never enjoy “Bette Davis Eyes” by Kim Carnes because it was playing on the car radio in June 1981 the evening my then-girlfriend broke up with me. No matter how much I might have admired the lyrics or production or catchy melody, I can’t get past the miserable memory of having been dumped while it was playing in the background.

But I want to focus on an occasion when music brings back fond memories of positive times. For me, the year was 1971, and the artist was Elton John.

But I want to focus on an occasion when music brings back fond memories of positive times. For me, the year was 1971, and the artist was Elton John.

For nearly every American music fan, Elton emerged pretty much overnight in January-February of that year when “Your Song” barreled up the US Top 40 charts and stayed in the Top Ten for a month. I was enthralled by the song — a gorgeous piano melody, embellished with strings and a light bass/drums accompaniment, and a strikingly original voice from this new British artist.

At that time, I was 15 and had been an avid album collector for nearly two years. Typically, when I heard a song that grabbed me, I would dash to my favorite record store and buy not just the single but the album, because I was eager to know if the artist had other songs worth hearing.

On the strength of “Your Song,” I put my money down for the LP entitled simply “Elton  John,” and what I discovered simply knocked me out. Instead of “more of the same,” the other nine songs exhibited an extraordinary synthesis of orchestrally arranged literary story-songs and funky Americana tunes that sounded like a hybrid of British chamber music and piano-driven Leon Russell tracks.

John,” and what I discovered simply knocked me out. Instead of “more of the same,” the other nine songs exhibited an extraordinary synthesis of orchestrally arranged literary story-songs and funky Americana tunes that sounded like a hybrid of British chamber music and piano-driven Leon Russell tracks.

The album stayed glued to my turntable for weeks, even months, on end. How astounding that the same record could include rollicking, upbeat rock (“Take Me to the Pilot” and “The Cage”), delicate madrigals (“Sixty Years On,” “First Episode at Hienton,” “The Greatest Discovery”), countryish Jagger parodies (“No Shoestrings on Louise”) and invigorating gospel (“Border Song”). What an exhilarating ride.

I took note of three names on the album credits — Lyricist Bernie Taupin, Producer Gus Dudgeon and Arranger Paul Buckmaster — who I soon came to realize were integral to  the Elton John Experience. The enigmatic words, the dynamic violin/cello backing, and the grand production values all played roles every bit as important as Elton’s stunning melodies, riveting piano work and one-of-a-kind vocal acrobatics, and a gripping bass-and-drums accompaniment.

the Elton John Experience. The enigmatic words, the dynamic violin/cello backing, and the grand production values all played roles every bit as important as Elton’s stunning melodies, riveting piano work and one-of-a-kind vocal acrobatics, and a gripping bass-and-drums accompaniment.

As Dudgeon explained in a 1995 interview, “The challenge we made for ourselves was to marry a big orchestra with a rock and roll section and make it work, and not have one of them lose out to the other. We were thrilled with the result, particularly on the final track, ‘The King Must Die.'”

It’s interesting to note that these recordings weren’t meant to be an official debut of Elton John the performer. Says Dudgeon, “That first album [Elton John] wasn’t really made to launch Elton as an artist; it was really made as a very glamorous series of demos for other people to record his songs. It was kind of like the American songwriter Jimmy Webb making an album and everyone rushes in to cover all of the songs on it. That was kind of the plan behind it.”

Still, it became Elton’s entrée, and that was certainly fine with me.

This kind of musical discovery might normally keep a listener like me happy for at least a year or two. But only a month later, in late February, I walked into the same record store and found another, newer Elton John album called “Tumbleweed Connection.” How could this be?

Turns out the first album had been recorded a full year earlier, in January 1970, and released in April, but we Yanks hadn’t learned of it for nine months. Meanwhile, Elton and his crew had returned to the studio with a new batch of songs in the summer of 1970 and released them in October.

Turns out the first album had been recorded a full year earlier, in January 1970, and released in April, but we Yanks hadn’t learned of it for nine months. Meanwhile, Elton and his crew had returned to the studio with a new batch of songs in the summer of 1970 and released them in October.

I couldn’t believe my good fortune. “Tumbleweed” was a concept album of sorts, with more Bernie Taupin lyrics that painted a nostalgic picture of the American West, a few country elements like harmonica and pedal steel guitar in the mix, and Buckmaster’s forceful strings and Dudgeon’s producing skills. And, of course, Elton’s riveting vocals and piano.

Now, suddenly, I had more Elton material to enjoy: quiet pieces like “Come Down in Time” and “Talking Old Soldiers,” refreshing countryish tunes like “Amoreena” and “Country Comfort” and instant classics like “Where to Now, St. Peter?” and “Burn Down the Mission.” Life was, indeed, great.

But wait. Now it’s March. I’m back in the record store and, on a garish pink album cover, the name “Elton John” appears. What?! This time, it’s a soundtrack LP, released  on another label, for an obscure French film called “Friends.” At this point, I’m so crazy about anything Elton that I buy it and take it home.

on another label, for an obscure French film called “Friends.” At this point, I’m so crazy about anything Elton that I buy it and take it home.

I find that it’s like most soundtrack albums — a lot of mostly tedious film score — but sure enough, there are four or five “diamonds in the rough”: the rock/funk of “Can I Put You On” and “Honey Roll,” but more important, the gorgeous melodies of “Michelle’s Song,” “Seasons” and “Friends.” These are great Elton-Bernie compositions, again produced by Dudgeon and laden with Buckmaster strings, every bit as appealing to me as the best of the first two LPs.

Now comes the emotional connection.

It was at this time in that same calendar year that I found myself falling hard for a girl who I had met in January. We quickly learned that we shared the same love for all three of these first Elton John albums, and we listened to them together incessantly as our relationship evolved.

We wandered into a record store in early May and were both stunned to see yet another new Elton John LP in the racks. This was a live album called “11-17-70,” which captured an incendiary performance he had given at a New York record studio in front of about 100 fans for a live radio broadcast on November 17, 1970. Elton, accompanied by his bassist Dee Murray and drummer Nigel Olsson, wowed the small crowd with stretched- out renditions of six songs from his repertoire, giving us a solid hint of what he might sound like if we were lucky enough to ever see him in concert.

out renditions of six songs from his repertoire, giving us a solid hint of what he might sound like if we were lucky enough to ever see him in concert.

Dudgeon recalls, “This concert tape was being bootlegged like mad, so (record company mogul) Dick James rang me up and said, ‘Look, if I send you a tape of this broadcast, do you think there is an album in there?’ So I managed to find about 40 solid minutes, and he said, “Go ahead and mix it and we’ll put it out as an album.’ We did, and it was ultimately one of four albums that were put out in barely a year, which was just ridiculous, completely unheard of.”

These four Elton John albums will be indelibly etched in my mind as the soundtrack to my first important romantic relationship. We lived and breathed these albums together. Interestingly, it was the “Friends” soundtrack that elicits the sharpest memories, for we had the opportunity to see that slight little foreign film together at a local art film moviehouse that fall. The video images and the audio reveries combined to create a vivid picture that I can still see today.

How does music do that? It’s magic, really. Just last week, I heard on SiriusXM Radio’s “Deep Tracks” channel the live version of “Take Me to the Pilot,” and damned if it didn’t take me right back to the autumn of 1971, hanging out and listening to those great old Elton albums.

One other important part of this collection of early Elton memories is his strong December 1971 LP, “Madman Across the Water,” which includes more epic productions like “Tiny Dancer” (which enjoyed new life after being prominently featured in the 2000 film “Almost Famous”), “Levon” and the amazing title track. All of these utilize the same signature Buckmaster string arrangements and Dudgeon production qualities. Dudgeon is quoted as saying, “That orchestral riff on the outro of ‘Levon’ is the greatest arrangement I’ve ever heard.”

One other important part of this collection of early Elton memories is his strong December 1971 LP, “Madman Across the Water,” which includes more epic productions like “Tiny Dancer” (which enjoyed new life after being prominently featured in the 2000 film “Almost Famous”), “Levon” and the amazing title track. All of these utilize the same signature Buckmaster string arrangements and Dudgeon production qualities. Dudgeon is quoted as saying, “That orchestral riff on the outro of ‘Levon’ is the greatest arrangement I’ve ever heard.”

As everyone knows, Elton John went on to become one of the most successful musical personalities of the past half-century. He has sold more than 300 millions albums, a preposterous achievement. He has given us 30 studio albums, of which half reached the Top 20 and five went to #1. There are 30 Top Ten Elton John singles, numerous compilations, collaborations, even a Disney film soundtrack (“The Lion King”). His remake of “Candle in the Wind” in honor of Lady Diana’s 1997 death is the best-selling single in Billboard history.

But for me, things started going south in late 1972, around the same time my girlfriend  moved out of state and we went our separate ways. I don’t know if it’s a coincidence that Elton started writing what I felt was more disposable commercial stuff at that same time (“Honky Cat,” “Crocodile Rock,” “Bennie and the Jets,” “The Bitch is Back”). These songs and others like it may have thrilled the masses and sold millions of copies, but they didn’t do much for me. I just couldn’t connect to them emotionally, and I can’t deny that a huge reason for that is the overly flamboyant Liberace-like persona he chose to adopt at that point. It was just too much, too far removed from the Elton John I fell for in early 1971.

moved out of state and we went our separate ways. I don’t know if it’s a coincidence that Elton started writing what I felt was more disposable commercial stuff at that same time (“Honky Cat,” “Crocodile Rock,” “Bennie and the Jets,” “The Bitch is Back”). These songs and others like it may have thrilled the masses and sold millions of copies, but they didn’t do much for me. I just couldn’t connect to them emotionally, and I can’t deny that a huge reason for that is the overly flamboyant Liberace-like persona he chose to adopt at that point. It was just too much, too far removed from the Elton John I fell for in early 1971.

Oh sure, I still enjoyed isolated 1970s Elton John songs like “Mona Lisas and Mad Hatters,” and albums like “Goodbye Yellow Brick Road.” And years down the road, I fully appreciated high-quality work like 1989’s “Sacrifice,” 1992’s “Emily,” 2006’s “Postcards From Richard Nixon” and 2013’s “Home Again.”

But for the most part, his music would never again reach me the way his early work did.

And I guess that’s my point. Certain songs, certain albums, certain times in an artist’s career can have a way of making a greater impact on us because of what’s going on in our lives at the time we hear and experience them. That’s just the way it is.

Here’s to you, Sir Elton. Thank you for making an important difference in my life at a very impressionable time.

And may all my readers be fortunate enough to have similar life-changing experiences with other songs, albums, and artists. Something tells me you probably already have.

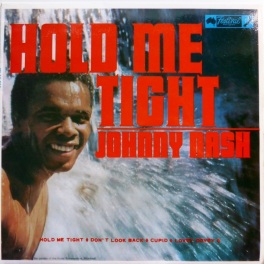

Its first appearance here, it’s generally agreed, came when an American-born artist — Johnny Nash, a Houston-based pop singer-songwriter — took his version of Jamaica’s indigenous music to #5 on the U.S. charts in 1968 with the catchy “Hold Me Tight.” But if record companies were expecting to then cash in on a flood of reggae songs and bands, it didn’t happen. (At least not yet.)

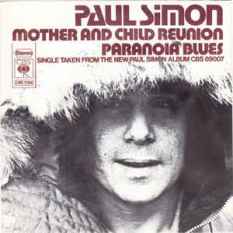

Its first appearance here, it’s generally agreed, came when an American-born artist — Johnny Nash, a Houston-based pop singer-songwriter — took his version of Jamaica’s indigenous music to #5 on the U.S. charts in 1968 with the catchy “Hold Me Tight.” But if record companies were expecting to then cash in on a flood of reggae songs and bands, it didn’t happen. (At least not yet.) So reggae went back into hiding for a few years until the great Paul Simon, always curious about “world music” and intriguing new rhythms, visited Kingston in 1971 to record his new song “Mother and Child Reunion.” He admired reggae artists like Jimmy Cliff and Desmond Dekker and wanted to explore the music further at its source, using Jamaican musicians who instinctively knew the way it should be played. He invited Cliff’s backing group to accompany him on the recording, and the result was also a #5 hit that put reggae back in the public eye.

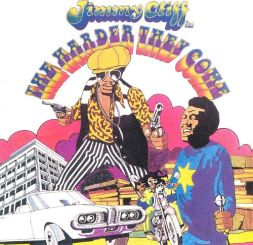

So reggae went back into hiding for a few years until the great Paul Simon, always curious about “world music” and intriguing new rhythms, visited Kingston in 1971 to record his new song “Mother and Child Reunion.” He admired reggae artists like Jimmy Cliff and Desmond Dekker and wanted to explore the music further at its source, using Jamaican musicians who instinctively knew the way it should be played. He invited Cliff’s backing group to accompany him on the recording, and the result was also a #5 hit that put reggae back in the public eye. The attention Cliff gained from that connection helped him later that year when he released “The Harder They Come,” the soundtrack album to the movie of the same name (in which he also starred). The film, a crudely made crime drama, was largely ignored but later became a favorite with the midnight-movie crowd.

The attention Cliff gained from that connection helped him later that year when he released “The Harder They Come,” the soundtrack album to the movie of the same name (in which he also starred). The film, a crudely made crime drama, was largely ignored but later became a favorite with the midnight-movie crowd. play it. I just knew we weren’t doing it right.

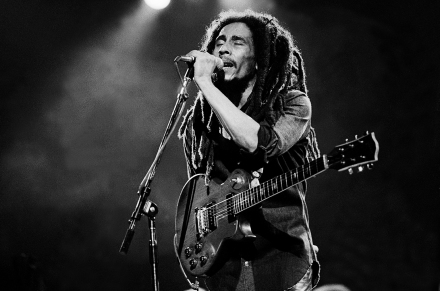

play it. I just knew we weren’t doing it right. He signed Marley to a lucrative contract in 1973, let him loose in his studios in the Bahamas and England, and sat back and waited. The debut LP, “Catch a Fire,” marked the first time a reggae band had access to a state-of-the-art studio and were accorded the same care as their rock ‘n’ roll peers. Blackwell, hoping to create “more of a drifting, hypnotic-type feel than a rudimentary reggae rhythm,” restructured Marley’s arrangements and supervised the mixing and overdubbing.

He signed Marley to a lucrative contract in 1973, let him loose in his studios in the Bahamas and England, and sat back and waited. The debut LP, “Catch a Fire,” marked the first time a reggae band had access to a state-of-the-art studio and were accorded the same care as their rock ‘n’ roll peers. Blackwell, hoping to create “more of a drifting, hypnotic-type feel than a rudimentary reggae rhythm,” restructured Marley’s arrangements and supervised the mixing and overdubbing. pop charts, the album soared to #8 and the 1977 followup “Exodus” (with the FM hits “Jammin’,” “Waiting in Vain” and “Three Little Birds”) was a respectable #20.

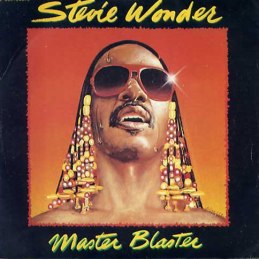

pop charts, the album soared to #8 and the 1977 followup “Exodus” (with the FM hits “Jammin’,” “Waiting in Vain” and “Three Little Birds”) was a respectable #20. In America, Motown/funk superstar Stevie Wonder was so taken by reggae in general, and Marley in particular, that he wrote a tribute to him in 1980 called “Master Blaster (Jammin’),” which became a #5 hit in the US and #2 in England. Marley and Wonder even performed several shows together that summer.

In America, Motown/funk superstar Stevie Wonder was so taken by reggae in general, and Marley in particular, that he wrote a tribute to him in 1980 called “Master Blaster (Jammin’),” which became a #5 hit in the US and #2 in England. Marley and Wonder even performed several shows together that summer. since then, most notably Ziggy in the late ’80s (particularly “Tomorrow People” in 1988) and Damien in the ’90s, perpetuating and growing the reach and influence of reggae music as their father intended.

since then, most notably Ziggy in the late ’80s (particularly “Tomorrow People” in 1988) and Damien in the ’90s, perpetuating and growing the reach and influence of reggae music as their father intended.