Here’s a song for a friend soon gone

I should begin this week’s post with this caveat to my readers: If you’re not from Cleveland, or at least from the Midwest, you’re probably going to be scratching your head and wondering, “Who is Michael Stanley?”

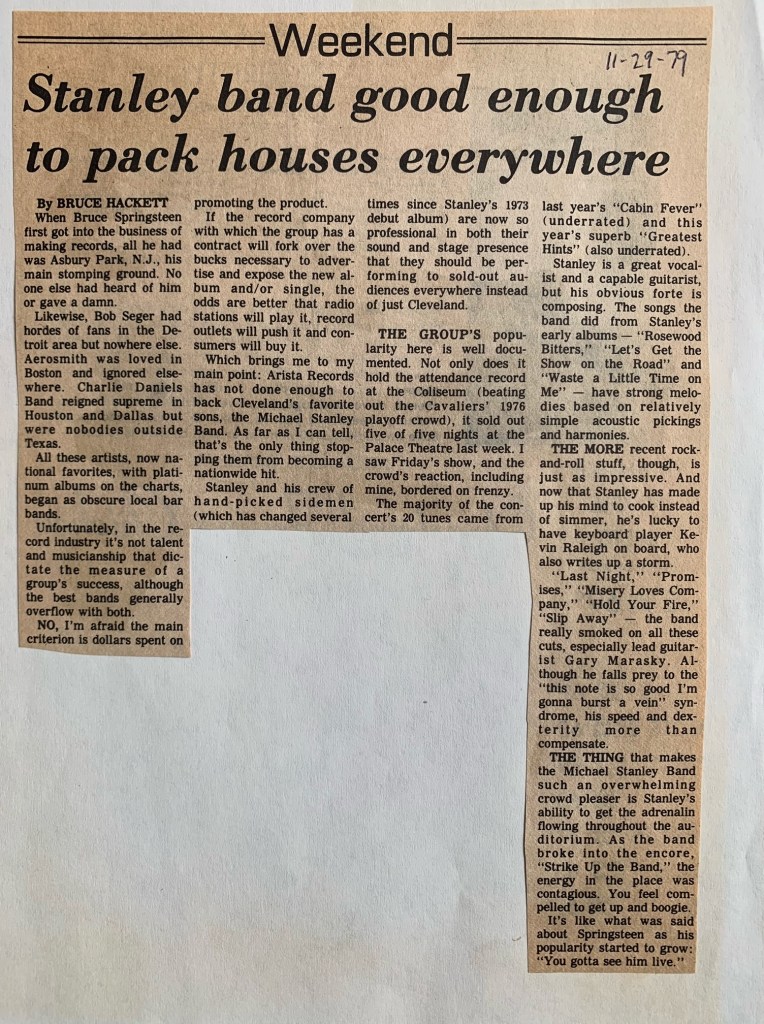

Holly Gleason, a Cleveland-based writer, put it succinctly in a piece she wrote in the wake of Stanley’s passing last week: “Like a secret handshake, you can still measure the rock and Midwestern bonafides of people, especially those who grew up in Ohio and surrounding states in the ‘70s and ‘80s, by whether they knew The Michael Stanley Band. In Cleveland, especially, Stanley was an artist who felt every bit as important as Detroit’s Bob Seger, Indiana’s John Mellencamp and even Jersey’s Bruce Springsteen, who also captured working class lives, loves and disappointments with an authenticity as gritty as it was charged.”

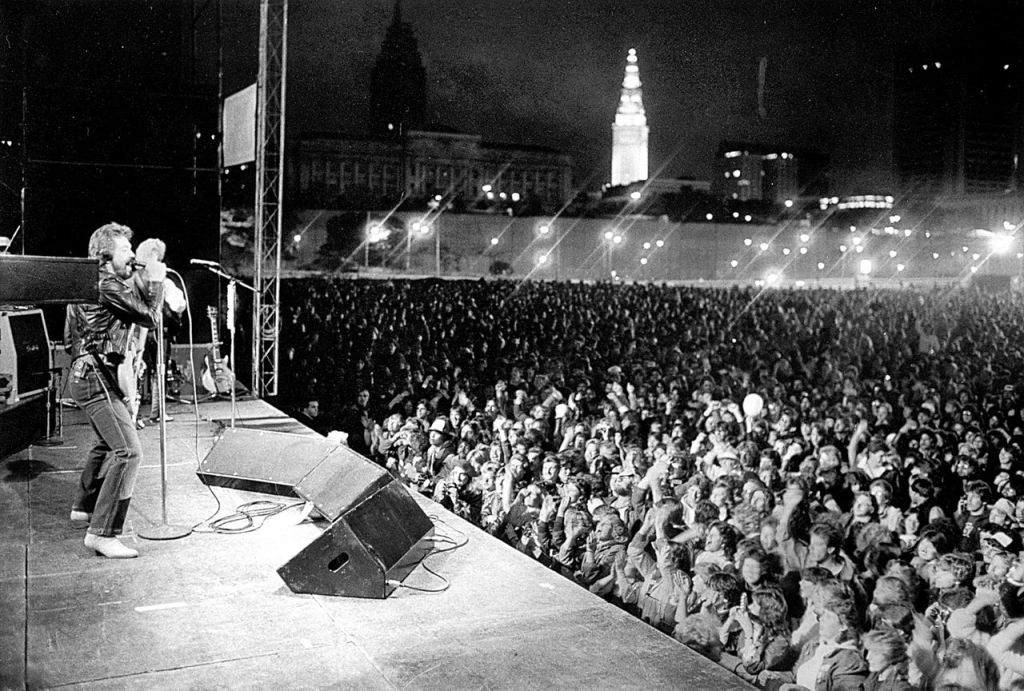

The difference between Stanley and those nationally known rock stars was that, despite relentless efforts over many years, he never could get the broader recognition his music so richly deserved. In the big cities and small towns of the Great Lakes area, The Michael Stanley Band — or MSB, as his fans called them — were enormously popular from the mid-’70s through the mid-’80s and beyond, setting attendance records at major venues that still stand decades later.

Stanley was seven years older than I am, so he was 26 and I was 19 when I was first introduced to his music when my friend Mark loaned me his copy of Stanley’s 1974 LP “Friends and Legends.” I had begun hearing his exceptional tune “Let’s Get the Show on the Road” on WMMS-FM, Cleveland’s hugely influential rock radio station, and I wanted to hear more. The following summer, Stanley joined forces with guitarist/singer Jonah Koslen, bassist Dan Pecchio and drummer Tommy Dobeck to form the Michael Stanley Band. I picked up their first album, “You Break It, You Bought It,” and became rather obsessed with it, especially the rockers “I’m Gonna Love You” and “Step the Way” and the ballads “Waste a Little Time on Me” and “Sweet Refrain,” all of which benefitted from the capable hands of producer Bill Szymczyk.

In the summer of ’76, I was eager to see the farewell tour of Loggins and Messina at Blossom Music Center, the wonderful amphitheater nestled into the Cuyahoga Valley between Cleveland and Akron. The bonus for me was my first exposure to MSB in concert, who served as the warm-up act that evening. Loggins and Messina, who knew next to nothing about Stanley and company, must’ve been thoroughly puzzled and impressed by the over-the-top response to MSB’s show by the loud and loyal Northeast Ohio fans in attendance.

I kept waiting for these guys to make a splash on the national charts, both singles and albums, but it didn’t happen, not for 1976’s “Ladies’ Choice” or the 1977 double live album “Stagepass,” recorded at Cleveland’s storied rock venue, The Agora. When Koslen left the band to form his own group Breathless, and then MSB were dropped by Epic Records, I figured, oh well, just another band that didn’t make it. What a shame.

But no. They added guitarist Gary Markasky on lead guitar and keyboardists Bob Pelander and Kevin Raleigh, and signed with Arista Records, run by the mercurial Clive Davis. Stanley’s new songs, plus a few by Raleigh and Pelander, had a punchier “straight-ahead rock” feeling, as Stanley himself would describe them, punched in nicely by producer Robert John “Mutt” Lange. To my ears, “Misery Loves Company” or “Who’s to Blame” from 1978’s “Cabin Fever” should’ve been big hits, or “Last Night” or “Hold Your Fire” from 1979’s “Greatest Hints,” (and let’s not overlook the stunning ballads “Why Should Love Be This Way” and “Beautiful Lies”). Inexplicably, Davis was only lukewarm on these tracks and chose not to promote the LPs sufficiently, ultimately giving up on the group.

Then came EMI America, who signed MSB in 1980 during sessions for “Heartland,” their first brush with Billboard charts fame. “He Can’t Love You,” which included the unmistakable sax playing of The E Street Band’s Clarence Clemons, reached #33 but stalled there, and the album never rose past #86. Other lineup changes came (Michael Gismondi on bass, Danny Powers on lead guitar, Rick Bell on sax), and EMI chose to stick with the band for three more stellar LPs — “North Coast,” “MSB” and “You Can’t Fight Fashion” — but despite constant touring behind huge acts, they never achieved consistent headliner status outside Ohio, Michigan, Pennsylvania and a few other cities like St. Louis.

I was a rock music critic in Cleveland during this period, and I wrote appreciative profiles and glowing concert reviews of MSB. One review even sparked a letter from Stanley himself, thanking me for being supportive! I interviewed him over lunch one time and found him to be incredibly gracious and approachable. Indeed, when I asked our staff photographer to take one photo of Stanley with me for my bulletin board at home, Stanley didn’t hesitate to put his arm around my shoulder. Such a genuinely nice guy.

Once EMI dropped the band, MSB threw in the towel…but that didn’t stop Stanley from writing and performing his music. He played shows regularly throughout Northeast Ohio with former MSB members, with another gang of musician friends he called The Resonators, and as Michael Stanley and Friends. More important, he continued writing really great songs and recording them on independent labels at the rate of nearly one studio album every year from 1995 through 2017, plus a couple of live collections.

I saw MSB and or Stanley solo seven times in the ’70s and ’80s, often at Blossom as part of sold-out crowds. The electric atmosphere at those gigs reminded me of the rabid crowds at Springsteen shows. More recently, I saw him perform in December 2019 at MGM Northfield Park, and the place was packed with fervent fans who had clearly grown up with MSB’s music, and could (and did) sing along on damn near every song in the set list. It was those people I thought about this past week when the reality of Stanley’s death from lung cancer truly hit me.

As Gleason put it, “Michael Stanley saw us. He knew what we were thinking and feeling, and the reality of how it felt being the great unseen and never-heralded. He took it all in, twisted that truth into three, four, five visceral minutes, and sent our lives into the world with an actual dignity and understanding… He saw us — young, hungry, dreaming of something more, not even sure what it was. He felt our urgency, and he put it in songs.”

I moved away from Cleveland in 1995, first to Atlanta and then Los Angeles, so I wasn’t around much to see him take on a new career as a TV personality, hosting evening talk/entertainment programs for several years. But I was hip to his fine work behind the microphone as the afternoon drive-time DJ on classic rock radio station WNCX in Cleveland, a position he held from 1990 until just a few weeks ago when his failing health would no longer allow it. Whenever I came to town for visits, I always tuned my car radio to his show, which offered excellent classic rock selections interspersed with his soothing, familiar voice. It was like sliding into a pair of comfortable old shoes.

Over the years, I have relished the opportunity to turn on my friends in Atlanta and L.A. and elsewhere to the Michael Stanley Band. Invariably, after I offered up musical perfection on tracks like “Spanish Nights,” “In Between the Lines” and the irresistible “Lover,” they asked me, “Why weren’t these guys bigger stars?” I could only shrug my shoulders and shake my head in resignation.

David Spero, a former WWMS DJ and Stanley’s first manager, and a lifelong friend of Stanley, always felt his songs were his strong suit, and I’m inclined to agree. They’re smartly constructed, with intelligent, thought-provoking lyrics that capture the work ethic and passion for life that his fans have lived by. Said Spero, “I think he’s probably one of our country’s most underappreciated writers in that kind of Bob Seger/Bruce Springsteen style of storytelling.”

Stanley, born and raised in the suburbs of Cleveland and a stalwart resident ever since, said in a 2019 interview, “I had three pretty good, separate careers in music, TV and radio. Did we accomplish everything we wanted to? No. But we accomplished things we never thought of. I’ve been making a living doing something I love. This is what I dreamed about as a teenager, and I ended up doing it.”

That’s what I mean about the unabashed sincerity of the man. In a recent social media post, Jackie, a woman I worked with in public relations, recalled a time she spent the better part of a day in the ’90s driving Stanley around in a golf cart at a promotional event. “I can still remember how kind and cool, how slyly funny and completely down to earth he was that day. It’s nice when people are as you hope they’ll be.”

Michael Belkin, whose father served as manager for Stanley for 40 years, said, “In my entire career, I have never seen another artist as patient and polite as Michael was with fans. Backstage, at pre- and post-show meet & greets, dinners and benefits, I saw him interact with thousands of supporters over the years, and he was consistently pleasant and gracious. Always. Every time.”

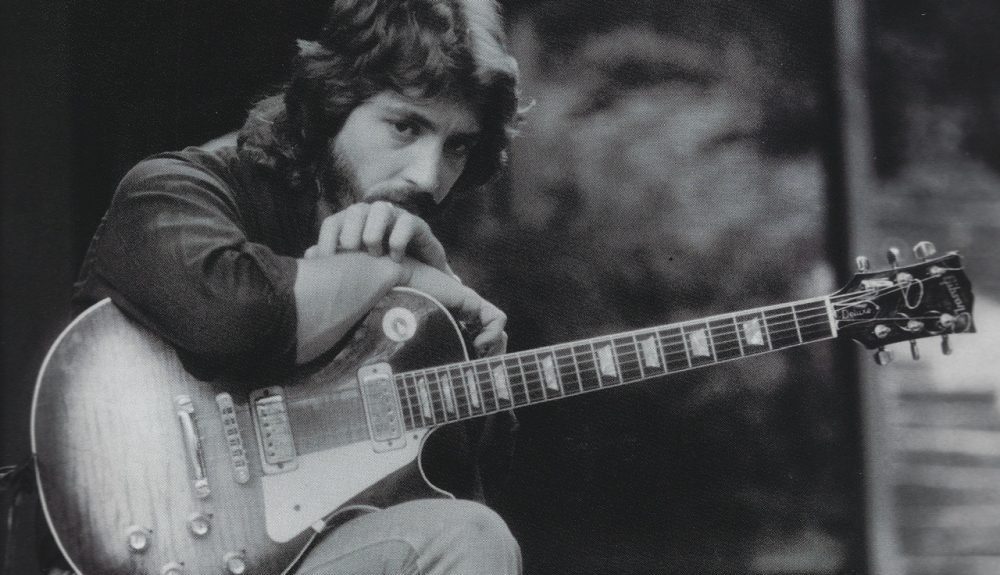

The great guitarist Joe Walsh, who played on Stanley’s early solo LPs, had this to say last week: “Michael was the king of Cleveland, and of course, the Michael Stanley Band became a Midwest powerhouse. Michael has always been a master at the craft of songwriting. His songs have a way of getting in your head and became songs you end up singing to yourself over and over from then on. His music will always be part of me.” (In fact, Walsh recorded Stanley’s tune “Rosewood Bitters” on his 1985 album “The Confessor.”)

In 2012, Stanley was asked about his legacy. His reply? ““If you look back at any writer’s body of work, you usually find a common theme or two that they’ve been trying to hone. I realized that mine is: You just never know. This whole idea of never knowing what tomorrow is going to bring and being open to it.”

Indeed, on Stanley’s 2014 album “The Job,” there’s a marvelous tune aptly titled “You Just Never Know”: “You just got to take it, just got to be there, /Just got to hold on ’cause you just never know, /Just got to take the fight into the heart of another night, /And just got to hold on ’cause you just never, just never know…”

***************************

If you’re intrigued by this band you’ve never heard of, or want to immerse yourself in their catalog and commiserate our collective loss with like-minded fans, have I got a playlist for you! It’s roughly chronological, from early solo albums through the nine MSB albums to Stanley’s latter-day LPs, with a few strong covers he recorded along the way. I think you’ll agree that this was a band who coulda-woulda-shoulda been much bigger across the country.