You know the groove’s still there

Most of the posts and playlists I put together here at Hack’s Back Pages have themes. Songs about autumn… Cringeworthy songs… Great ex-Beatles tunes… Songs with female names as the title… Songs for April Fool’s Day…

Some groupings, however, are seemingly random — strange mixes of genres, tempos, year of release, lyrics topics. That’s because these are what I call “lost classics.” Typically, the only thing they have in common is that they’re great songs that you maybe heard once before, or maybe a few times, but you haven’t heard in ages or have forgotten about. Or perhaps you’ve never heard some of these songs at all.

In any case, you’re just going to have to trust me. I think my track record for selecting dusted-off gems is pretty good, and I’ll wager that after hearing this playlist of a dozen songs from the ’70s (and a couple from the ’80s), you’ll come away with at least three or four “new” songs that hit your sweet spot. That’s the fun of lost classics — exciting discoveries of long-neglected musical jewels!

The Spotify playlist is at the end for you to access as you read more about the tracks. Enjoy!

****************************

“People Gotta Move,” Gino Vannelli, 1974

I remember going to an audio store in 1974 to buy new speakers, and when the sales guy dropped the needle on an album to test the sound of various brands of speakers, the record he chose to use was “Powerful People,” a new album by a Canadian singer named Gino Vannelli. The track was “People Gotta Move,” an infectious, keyboard-driven tune that knocked me off my feet (and eventually reached #22 on US charts that year). In addition to new speakers, I also bought Vannelli’s LP and it’s been a favorite of mine ever since. Four years later, his “Brother to Brother” LP reached #3 on the US charts, thanks to the #4 hit “I Just Wanna Stop,” but I still prefer the sound and excitement of his early work. Crank this one up LOUD!

“Without Love,” Southside Johnny & The Asbury Jukes, 1977

I’d become a major Bruce Springsteen fan in the summer of ’75, playing his first three LPs incessantly and bowled over when I saw him in concert at a Cleveland theater. While in college at Syracuse the following year, I began hearing great things about a New Jersey cohort of Springsteen named “Southside” Johnny Lyon, so when he came to campus to play a small club with his rollicking R&B band The Asbury Jukes, I eagerly attended, and have loved this group ever since. Their second LP, 1977’s “This Time It’s For Real,” is full of irresistible dance tracks, many written by Steve Van Zandt and Springsteen, but my favorite is “Without Love” by songwriter Carolyn Franklin, younger sister of Aretha Franklin. Southside Johnny and his horn section are in top form on this slab of vintage soul.

“Lucretia MacEvil”/”Lucretia’s Reprise,” Blood, Sweat & Tears, 1970

I was among the millions who loved BS&T’s 1969 album with its original use of horns and jazz arrangements in a rock format, and singer David Clayton-Thomas’s gutsy vocals on big hits like “You’ve Made Me So Very Happy,” “Spinning Wheel” and Laura Nyro’s “And When I Die.” I played the hell out of this LP, which also included sharp interpretations of Traffic’s “Smiling Phases” and Billie Holiday’s “God Bless the Child.” The follow-up album, “3,” turned out to be a big disappointment, but it included “Hi-De-Ho,” a stirring gospel track by Carole King, and Clayton-Thomas’s own “Lucretia MacEvil,” a modest hit at #29. The group tacked on a nifty jazz-horns coda entitled “Lucretia’s Reprise” that extends the song’s groove an extra three minutes.

“Dissatisfied,” Fleetwood Mac, 1973

First, there was Peter Green’s Fleetwood Mac, founded in London in 1967 as a blues band led by Green’s superb guitar. In the late ’70s and into the ’80s, Fleetwood Mac was a super-platinum group pumping out multiple hit pop singles, led by guitarist Lindsay Buckingham and singer Stevie Nicks. In between those two versions, in the 1970-1975 period, there was a more eclectic period featuring the diverse songs of two guitarists (Brit Danny Kirwan and American Bob Welch), and the marvelous Christine McVie, whose singing and songwriting have been the most consistently superior of them all. On the otherwise ho-hum 1973 LP “Penguin,” she serves up the catchy pop rock of “Dissatisfied,” which resembles her later successes like “You Make Loving Fun” and “Little Lies.”

“Throwing Stones,” Grateful Dead, 1987

The late great Jerry Garcia got most of the accolades as the musical epicenter of this venerable band, and deservedly so, but I have always been equally fond of the singing and songwriting of bandmate Bob Weir. That’s his voice you hear on classics like “Truckin’,” “Sugar Magnolia” and “One More Saturday Night,” and his stellar contributions to the group’s superb 1987 comeback studio album “In the Dark” are arguably that record’s finest moments. There’s Weir’s compelling rocker “Hell in a Bucket,” and there’s the relentless beat and social commentary behind “Throwing Stones”: “And the politicians throwing stones, so the kids, they dance, they shake their bones, /’Cause it’s all too clear we’re on our own, singing ashes, ashes, all fall down…”

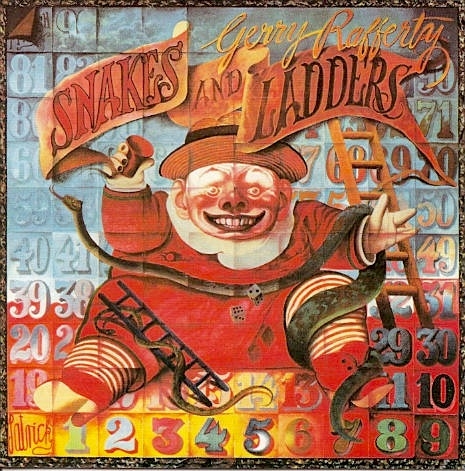

“Wastin’ Away,” Gerry Rafferty, 1980

The smooth voice and beautifully constructed songs of Gerry Rafferty seemed to come out of nowhere in the summer of 1978, particularly the majestic hit “Baker Street” with its killer sax riff. Actually, Rafferty may have sounded vaguely familiar because he was the singer in the band Stealers Wheel, who had a 1973 hit with “Stuck in the Middle With You.” He followed up his #1 LP “City to City” with “Night Owl” (1979) and “Snakes and Ladders” (1980) and more sporadic releases in subsequent years, but because he had an aversion to performing and touring, the albums didn’t get the promotion they needed, and his chart success dwindled. Such a shame, because a fine track like “Wastin’ Away” from “Snakes and Ladders” could’ve been a hit.

“Sit Yourself Down,” Stephen Stills, 1970

From his Buffalo Springfield days (“For What It’s Worth,” “Bluebird,” “Rock and Roll Woman”) through his Crosby, Stills, Nash and Young period (“Suite: Judy Blue Eyes,” “Helplessly Hoping,” “Carry On”), Stephen Stills became known as a terrific songwriter, not to mention guitarist and multi-instrumentalist. The egos of CSN&Y were too big and stubborn to allow the group to last long, but that didn’t stop the individual members from proceeding with solo careers and/or other groups. Stills came out of the gate with the strong “Stephen Stills” LP and its single, “Love the One You’re With,” in late 1970, and it was packed with fine tunes and top-flight musicians. You might recall “Sit Yourself Down,” which features Crosby, Nash, Rita Coolidge and Cass Elliot on background vocals.

“Carolina Day,” Livingston Taylor, 1970

James Taylor’s younger brother shares a similar singing/songwriting talent and was able to secure his own recording contract at age 20, not long after “Sweet Baby James” was released in mid-1970. Livingston was pretty prolific, releasing six albums in ten years (inching into the Top 40 twice with singles but never with LPs), and he continued recording new songs periodically in the ’80s, 90s and 2000s. The debut LP “Livingston Taylor” showed a strong vocal resemblance to James, and the ten original songs by Liv were strong, but the album’s production sounded a bit amateurish. The upbeat debut single “Carolina Day,” which had “hit” written all over it, curiously stiffed at #93. Its lyrics reference his siblings and their growing-up-in-Carolina experiences.

“Nature’s Way,” Spirit, 1970

Emanating out of the rustic Topanga Canyon area of Malibu, California, in 1968, Spirit was a rock/jazz/blues band that had some modest chart success but was more a proud FM underground favorite. Their first two albums flirted with the US Top 25, thanks to the minor hit singles “Fresh Garbage” and “I Got a Line on You.” For their fifth album, they came up with a quasi-concept LP, “The Twelve Dreams of Dr. Sardonicus,” which used literary themes to examine the fragility of life and complexity of the human experience. The sardonic “Mr. Skin” became a dance favorite upon its re-release as a single in 1973, but the track from “Dr. Sardonicus” that became a signature song for Spirit was the ecologically prescient “Nature’s Way,” an acoustic song by guitarist Randy California.

“Easy Now,” Eric Clapton, 1970

During his days with The Yardbirds, John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, Cream and Blind Faith, Clapton concentrated almost exclusively on electric blues guitar, shying away from the microphone except perhaps to add a harmony. He deferred to Keith Relf, Mayall, Jack Bruce and Steve Winwood, respectively, because he had no confidence in his singing voice. Then Clapton befriended Delaney Bramlett, with whom he collaborated on tour with Delaney and Bonnie’s band and, more important, on writing songs together. Bramlett wisely pushed Clapton to make his first solo album and to do all the lead vocals, and the result was the 1970 LP “Eric Clapton,” which features the guitarist’s lovely voice, and includes classics like “After Midnight,” “Let It Rain,” “Blues Power” and the acoustic guitar-based love song “Easy Now.”

“Someone to Lay Down Beside Me,” Karla Bonoff, 1977

A close-knit fraternity of songwriter musicians based in Los Angeles played and sang on each other’s songs throughout the mid-late 1970s, and one of the most talented singer-songwriters of the bunch was Karla Bonoff. She won plenty of acclaim for the excellent tunes in her portfolio recorded by others — “All My Life,” “Isn’t It Always Love,” “Home,” “Wild Heart of the Young” and “Lose Again” — but never had much chart success herself, which is a crying shame. Her four LPs between 1977 and 1988 are all beautifully recoded keepers in my vinyl collection. Linda Ronstadt cast such a long shadow with her versions of Bonoff’s songs, especially the gorgeous “Someone to Lay Down Beside Me,” but I maintain that Bonoff’s rendition is the better of the two. Listen and decide for yourself.

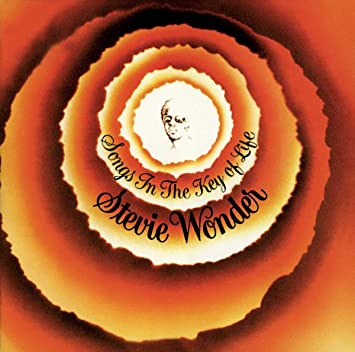

“Summer Soft,” Stevie Wonder, 1976

From 1972-1977, it seemed that Wonder could do wrong. “Innervisions” (1973), “Fulfillingness’ First Finale” (1974) and “Songs in the Key of Life” (1976) all won Album of the Year Grammy awards, not to mention a string of Top 10 singles in the same time perioda. In particular, “Songs in the Key of Life” is a monumental double LP that offers an amazing smorgasbord of musical genres and lyrical explorations, with Wonder in firm command of his songwriting gift. The funky stomp “I Wish” and Wonder’s Duke Ellington tribute “Sir Duke” got the lion’s share of attention, but there are equally worthy tracks to savor, like “As,” “Another Star,” “Isn’t She Lovely,” “Ngiculela (I Am Singing),” “If It’s Magic,” “Love’s in Need of Love Today” and the melodic, heartbreaking “Summer Soft.”

**************************