Disappointment haunted all my dreams

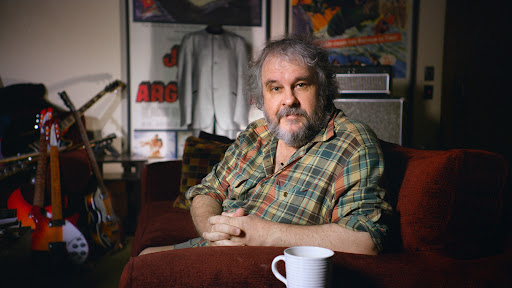

Mention the name Michael Nesmith, and casual observers of classic rock music might not recognize it. Fans of The Monkees will surely remember him as the tall guitar player wearing a wool hat who often served as the voice of reason amidst the zany chaos of their weekly TV comedy series that ran from 1966-1968.

But even fans of the band’s music and/or TV series might not know about Nesmith’s other notable accomplishments as a songwriter, band leader and video visionary. In light of Nesmith’s death last week at age 78, it seems appropriate to shed a little light on his life to broaden understanding of his talents and influence in the music business through the years.

But first, let’s get a little perspective:

I was only 11, so I didn’t really understand what was happening. I was pretty much a pawn in the show business game of foisting a product upon an unsuspecting public. It was September 1966, and overnight, I joined millions of other teens and pre-teens in becoming a huge fan of The Monkees.

“They’re going to be bigger than The Beatles!” I told my skeptical parents. “They even have their own weekly TV show!”

This was just what the show’s producers were counting on — gullible American kids buying into the sanitized Hollywood vision of what a rock band should look like and sound like: Four zany young guys with dreams of making it big, making their way through one silly weekly adventure after the next, always finding a way to work in a “performance” of at least one of their songs, which were often being heard concurrently on Top 40 radio.

And it worked. For a while.

The half-hour NBC-TV show “The Monkees” was an instant hit in the ratings. At the Emmy Awards nine months later, the program scored an upset by winning Outstanding Comedy Series, triumphing over shows with far better credentials like “Bewitched,” “Get Smart,” “The Andy Griffith Show” and “Hogan’s Heroes.”

On the Billboard Pop charts, the first singles and albums released by The Monkees all went to #1 and stayed there for many weeks on end. “I’m a Believer” was the #1 song in the nation for nearly three months. Here’s a fact that still astonishes me today: Year-end sales figures for 1967 show that more units of Monkees records were sold than The Beatles and The Rolling Stones combined!

But there was a fly in the ointment that soon derailed this runaway success. When the public learned that the band members weren’t really playing the instruments on the records they were hearing or on the TV performances they were seeing, there was a backlash from which they never fully recovered. Critics pounced, calling The Monkees “The Pre-Fab Four,” a derisive take on The Beatles’ “Fab Four” nickname. The TV show lasted only one more season through continually sagging ratings, and was cancelled in the summer of 1968.

Still, there were six commercially huge hit singles between September 1966 and March 1968 that cemented The Monkees’ name in pop music history. “Last Train to Clarksville,” “I’m a Believer,” “A Little Bit Me, A Little Bit You,” “Pleasant Valley Sunday,” “Daydream Believer” and “Valleri” all reached at least #3, with four of them topping the charts. They’re so ingrained in my head that I could sing you every word of these songs right now, today. But then the bottom fell out, with each successive single faring worse through 1968 and 1969, and by 1970, the jig was up.

In retrospect, the case can be made that the four individuals who comprised the band — Nesmith, Peter Tork, Davy Jones and Micky Dolenz — were just as much pawns in this show business game as anybody. They were hired not as musicians but as comic actors playing the roles of musicians in a TV sitcom.

Producer Bob Rafelson had come up with the concept of a TV show about a rock and roll group as early as 1960, but it wasn’t until The Beatles’ spectacular arrival and, more specifically, the success of their film “A Hard Day’s Night” in 1964 that Rafelson got the green light from Screen Gems, the TV arm of Columbia Pictures, to develop his idea. At first he thought of using an existing pop band to star in the program, but after being turned down by the likes of The Lovin’ Spoonful and The Dave Clark Five, he decided to manufacture his own group.

Rafelson concluded that Jones, whose Broadway acting pedigree had already won him a contract with Screen Gems and Columbia as an actor/singer, would be an ideal choice for this project, bringing a charming Brit-pop sensibility. The rest of the group would be found through auditions, just as was done with any other TV show at the time.

This was the ad copy that ran in Daily Variety and The Hollywood Reporter: “Madness! Auditions. Folk & Roll Musicians-Singers for acting roles in new TV series. Running parts for four insane boys age 17-21.”

Tork, a budding musician, won one of the three remaining parts, along with Dolenz, a former child actor who had starred in the inconsequential 1950s sitcom “The Circus Boy.” Rounding out the quartet was Nesmith, by far the best musician of the four, a competent songwriter/guitarist with a droll sense of humor and a business acumen inherited from his mother, an executive secretary who had invented “Liquid Paper” correction fluid and built it into a multi-million-dollar company.

The foursome did what was asked of them, learning their lines and playing their parts on the show. When they showed up at the recording studio, however, Nesmith and Tork were disappointed to learn their musical skills would not be needed. Dolenz and Jones were tapped to dub lead vocal parts onto the finished tracks. The show’s musical supervisor was the notorious Don Kirshner, who had selected Tommy Boyce and Bobby Hart from his stable of Brill Building pop songwriters to write and produce most of the songs for the group’s first album, “The Monkees,” which was essentially intended as a companion soundtrack to the TV show’s first season.

The first sign of trouble, as far as Nesmith was concerned, was when that debut LP appeared. “The first album showed up and I looked at it and my heart sank, because it made us appear as if we were a bonafide rock ‘n’ roll band. There was no credit given for the other musicians who actually played on the tracks. I went completely ballistic, and said, ‘What are you people thinking?’ And the powers that be said, ‘Well, you know, it’s the fantasy.’ I said, ‘It’s not the fantasy. You’ve crossed the line here. You are now duping the public. They know when they look at the television series that we’re not a rock ‘n’ roll band; it’s a show about a rock ‘n’ roll band. Nobody for a minute believes that we are somehow this accomplished rock ‘n’ roll band that got their own television show. You putting the record out like this is just beyond the pale.'”

Kirshner, irritated at Nesmith’s objections, plowed ahead, assembling a dozen more tracks recorded in the same manner and releasing them a mere three months later without the group’s knowledge as the second LP, “More of The Monkees.” Despite the fact that the album was a big commercial hit, Nesmith and the other Monkees had reached their breaking point about what they felt was nothing short of fraud. Nesmith persuaded the others to used their leverage to have Kirshner ousted, and The Monkees won creative control of all their recordings from then on.

On those initial two dozen recordings, the musical parts were handled largely by the seasoned pros who made up what was known in some circles as The Wrecking Crew. Some names you might recognize: guitarists Glen Campbell, James Burton and Louie Shelton; pianist Larry Knechtel (who later joined the soft-rock band Bread); drummer Hal Blaine; bassist Carol Kaye; percussionist Jim Gordon. Also contributing were Carole King, who wrote “Pleasant Valley Sunday” and added piano and backing vocals, and Neil Diamond, who wrote “I’m a Believer” and “A Little Bit Me, A Little Bit You” and added guitar.

It’s kind of unfair that The Monkees were singled out for not playing much on their own records. Truth be told, this wasn’t all that different from what occurred with other hip groups of the period. On several of the big hits released by The Beach Boys (“I Get Around,” “Help Me, Rhonda,” “Good Vibrations”) and The Byrds (“Mr. Tambourine Man”), the drums, bass, guitar and keyboard parts were played by Wrecking Crew session guys because the record label executives didn’t yet have confidence in the band members’ musical abilities.

Glenn Baker, author of “Monkeemania: The True Story of the Monkees,” put his finger on the real problem that tarnished The Monkees’ image, even to this day: “The rise of the ‘Pre-fab Four’ coincided with rock’s desperate desire to cloak itself with the trappings of respectability and credibility. Session players were being heavily employed by many acts of the time, but what could not be ignored, as rock disdained its pubescent past, was a group of middle-aged Hollywood businessmen had actually assembled their concept of a profitable rock group and foisted it upon the world. What mattered was that the Monkees had success handed to them on a silver plate. Indeed, it was not so much righteous indignation but thinly disguised jealousy which motivated the scornful dismissal of what must, in retrospect, be seen as an entertaining, imaginative and highly memorable exercise in pop culture.”

From my point of view as a teen in 1966-67, The Monkees were definitely entertaining. My friends and I held instruments and pretended to be Monkees in school skits, aping their movements and lip-synching their lyrics. The TV show offered half-hour escapes of mindless fun each Monday evening. Most of the controversy surrounding their legitimacy was, frankly, just not important to me at the time.

The freedom The Monkees won to control their recorded output was complicated by the fact that they didn’t share a common vision regarding the band’s musical direction. Nesmith favored leaning toward country rock and country blues, the direction his post-Monkees solo career would go. Jones fancied the more showy Broadway-type music, while Tork and Dolenz enjoyed dabbling in psychedelia and other more avant-garde genres. Still, they understood the need to maintain some continuity to what their young fan base expected, which was straightforward pop with accessible hooks.

Their 1967 singles “Pleasant Valley Sunday” and “Daydream Believer” are still enormously popular today, but their third and fourth LPs, “Headquarters” and “Pisces, Aquarius, Capricorn & Jones Ltd.,” exemplified the group’s inner turmoil and rudderless direction (although both nevertheless reached #1 on the album charts). By the time of the fifth LP, “The Birds, The Bees and The Monkees,” the TV show had been cancelled, and the experimental film and soundtrack they released in November 1968, “Head,” proved disastrous commercially, and Tork left the lineup. Efforts to continue as a threesome — 1969’s “Instant Replay” and 1970’s “The Monkees Present” — fell on deaf ears. The end had come.

Nesmith formed the First National Band in 1970 with songwriting partner John London and steel guitar legend “Red” Rhodes and released three LPs in the space of a year, full of songs Nesmith had been writing throughout the ’60s. But his role as a Monkee haunted him for years to come. His upbringing in Texas had given him his country music roots, and although his pop-star status tarnished his credibility among many musicians at the time, he is now mentioned in the same breath with The Byrds and The Flying Burrito Brothers as pioneers of the country rock genre.

(Remember “Different Drum,” the country flavored hit single from 1967 by The Stone Poneys, with then-unknown Linda Ronstadt on lead vocals? Nesmith wrote it.)

It’s interesting to note that both The Monkees’ music and TV show are now regarded with more respect than at their time of release. If you analyze some of the TV episodes, you’ll find, amidst the silliness, some groundbreaking creativity. During an era of formulaic domestic sitcoms and corny comedies, it was a stylistically ambitious show, with a distinctive visual style and tempo, an absurdist sense of humor and almost radical story structure. It utilized quick edits strung together with interview segments and even occasional documentary footage.

It rarely gets the credit for it, but The Monkees’ show was one of the essential pioneers of the music video format. Indeed, in 1979, Nesmith created and produced “PopClips,” a music video TV show that ran on Nickelodeon in 1980-81. He was also behind the VHS release of “Elephant Parts,” a collection of comedy sketches and music videos that saw significant sales in 1981 and won the first Grammy in the Music Video category that year. Warner Cable, who owned Nickelodeon, took Nesmith’s concept, made some minor adjustments, and launched MTV, the game-changing phenomenon of music delivery in the 1980s.

Writing in 2012 at the time of Jones’ death, columnist James Poniewozik said, “Even if ‘The Monkees’ never meant to be more than harmless entertainment and a hit-single generator, we shouldn’t sell it short. It was far better TV than it had to be. In fact, ‘The Monkees’ was the opening salvo in a revolution that brought on the New Hollywood cinema, an influence rarely acknowledged but no less impactful. As a pop culture phenomenon, The Monkees paved the way for just about every boy band that followed in their wake, from New Kids on the Block to ‘N Sync to the Jonas Brothers, while Davy set the stage for future teen idols David Cassidy and Justin Bieber. You would be hard pressed to find a successful artist who didn’t take a page from The Monkees’ playbook, even generations later.”

Numerous Monkees revival tours have been met with huge, adoring crowds, mostly aging Sixties kids looking for nostalgic memories. Ironically, MTV re-aired the TV show in the late ’80s, and a new generation of fans hopped on The Monkees’ train. New albums in 1987 (“Pool It!”) and again in 1996 (“Justus”) weren’t commercial or critical successes, but they served their purpose of keeping The Monkees name before the public. Tours usually featured only three of the four principals (either Nesmith or Tork holding out), but that didn’t seem to matter to those who bought tickets to see them.

Many middle-aged women wept in 2012 when their teen idol Davy Jones died of a heart attack at age 66. Social media activity was substantial and brought about increased sales of Monkees material. Dolenz, Tork and Nesmith collaborated once more on the praised 2016 album “Good Times!” which features several tracks written and sung by Nesmith ( “Me & Magdelena,” “I Know What I Know”).

In 2019, Tork died of cancer at age 77. Dolenz and Nesmith resumed touring in 2020 as “The Monkees Live: The Mike and Micky Show,” and their final performance came at the Greek Theater in L.A. in November of this year, only a month before Nesmith died of heart failure.

He may have had his share of disappointments, but his legacy is intact among those in the know.

**********************

The Spotify playlist below includes The Monkees’ biggest hits, plus Monkees songs written and/or sung by Nesmith, and a sampling of tracks from Nesmith’s solo career.