What’s it all about?

You all know me. I’m pretty transparent about my fascination with song lyrics and the stories behind the songs I love from the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s. I get a kick out of reading when songwriters let us in on what inspired them to write the words they do, the words I have memorized and continue to sing along with whenever I hear them. It gives my listening experience more depth and nuance when I learn how the music evolved or what sparked the idea for the song in the first place.

There’s this guy named Marc Myers who writes for the Wall Street Journal’s Arts section, where he fashioned a series of columns under the rubric “Anatomy of a Song.” He selected what he considered to be iconic tunes, interviewed the songwriters and other principal musicians, and laid out the who, what, where, when and why of these tracks in their own words. In 2016, Myers published a compendium of his columns titled “Anatomy of a Song: The Oral History of 45 Iconic Hits That Changed Rock, R&B and Pop.” (Why 45? Why not 50? Beats me.) I haven’t seen that first volume yet (it’s been ordered), but I came across its 2022 sequel recently, inventively titled “Anatomy of 55 More Songs” (at least I figured out why 55).

The songs hark from 1964-1996, roughly the same period that “Hack’s Back Pages” covers (1955-1990). I have taken the liberty of selecting eight of Myers’s choices and distilling the quotes and anecdotal info he provided to give you compelling tidbits of songs you surely know and revere. At the end, of course, is a Spotify playlist of these songs.

I intend to revisit this idea again in future posts, using Myers’s lists as a guide of sorts (although I’ll certainly be adding a few songs he chose not to include). And if you have a favorite you’d like to know more about, by all means, let me know!

**********************

“The Weight,” The Band, 1968

Robbie Robertson and his band The Hawks had toured and recorded behind Bob Dylan for three years in the 1965-1967 period, culminating in sessions at a house in Woodstock, New York, which were later released as “The Basement Tapes” in 1975. “We were just finishing up with Bob, and we had already written enough material for an album we would call ‘Music From Big Pink,’ our first album under our new name, The Band,” Robertson remembered. “But we needed one or two more. One evening I picked up my 1951 Martin D-28 acoustic guitar, holding it across my lap. I looked into the sound hole and saw the label that said “Nazareth, Pennsylvania,” where Martin Guitars are made. Seeing the word ‘Nazareth’ unlocked a lot of stuff in my head from Luis Buñuel’s “Nazarín,” a Mexican film about a priest with no possessions who travels the countryside. Once I’d written a few chords, I came up with “Pulled into Nazareth, was feeling ’bout half past dead.” I had no grand plan as to where the story might go, but the first thing he does is ask the first person he sees about a place to stay the night. A very biblical concept. I wanted various characters to unload their burdens on this guy. Take care of my dog, keep my friend company. You know, ‘Take a load off, and put it right on me.'” The song stalled at #63 on US pop charts upon release, but it became an Americana classic and was covered by many artists, including Aretha Franklin, The Staple Singers, Joe Cocker, Smith, Little Feat, King Curtis and Duane Allman, and The Grateful Dead.

“Year of the Cat,” Al Stewart, 1976

Stewart loved to tell stories with his songs, and in 1968 he wrote “Foot of the Stage” about a comedian contemplating suicide. Using the same melody, the song evolved in 1974 into “Horse of the Year,” about Princess Anne, an accomplished equestrian. Neither version was ever recorded. In 1975, Stewart saw a book about Vietnamese astrology, which his girlfriend had left on his kitchen table, open to a chapter entitled “Year of the Cat,” which was the zodiac sign for that year. “I looked at my ‘Horse of the Year’ song title, which seemed silly, while ‘Year of the Cat’ sounded really good,” he recalled. “Later that day, ‘Casablanca’ came on TV, and it occurred to me that the song should be about some exotic place where something memorable happened, all in the Year of the Cat. The opening line came to me: ‘On a morning from a Bogart movie, in a country where they turn back time.’ It was a novelistic approach, even cinematic. The woman in the song is no one specific, just an abstract fantasy. The guy is trying to make sense of what’s occurring, but she doesn’t give him time for questions.” Keyboardist Peter Wood had written the piano riff that became the introduction, and Stewart decided to add a middle section for various instrumental solos: strings, acoustic guitar, electric guitar and sax. Producer Alan Parsons turned it all into a six-minute tour de force that reached #8 on US pop charts in early 1977.

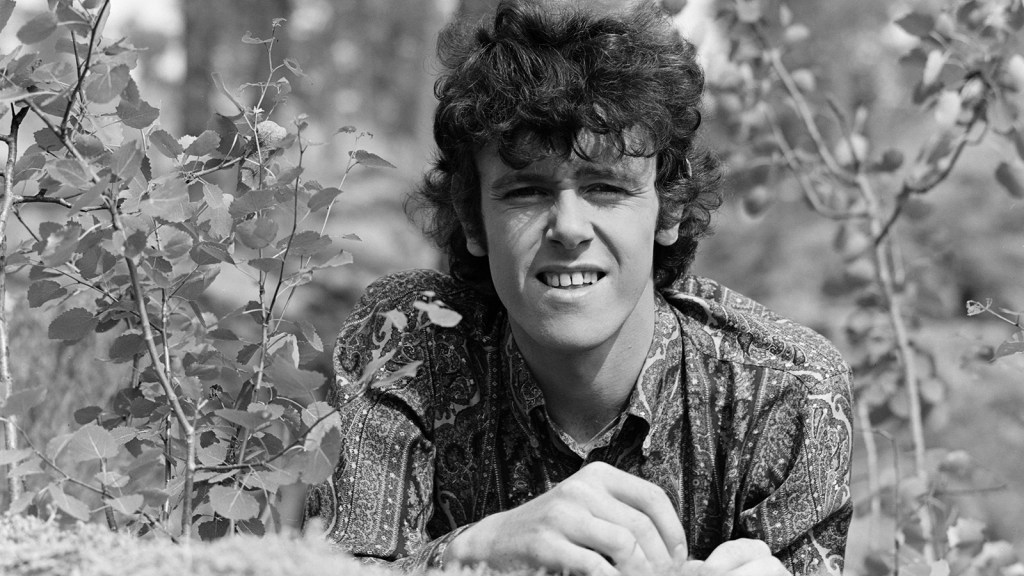

“Sunshine Superman,” Donovan, 1966

Donovan Leitch has said hearing “Sunshine Superman” brings back fond memories, even though its genesis came from unrequited love. “While in California promoting my first album and single, I met and fell for a woman named Linda,” he said. “We spent several weeks together, but she was still very fragile after breaking up with Brian Jones of The Rolling Stones, with whom she had had a child. So she turned down my marriage proposal, and I returned to England, but I missed her terribly and started writing a song about her. Like many of my songs, it expressed hopeful melancholy. I was miserable that it hadn’t worked out, but I felt optimistic it would someday: ‘When you’ve made your mind up, forever to be mine…’ ” The music used an unusual mix of harpsichord, tambura and acoustic bass and guitar, with half of what would become Led Zeppelin (Jimmy Page and John Paul Jones) on electric guitar and electric bass, respectively, which gave it what became known as a psychedelic pop vibe. Some heard veiled references to LSD (“I could’ve tripped out easy…” and “sunshine” was slang for acid), but Donovan denied it, saying “it was about how I could’ve slipped into depression but didn’t. Superman had nothing to do with the superhero or physical power. It was a reference to Frederich Nietzsche and the evolution of consciousness to reach a higher superman state.” This was all groundbreaking stuff for the US Top 40, and it went on to become his only #1 hit, and one of four Top Ten singles here.

“Peg,” Steely Dan, 1977

In 1976, as Donald Fagen and Walter Becker were beginning to work on the songs that would comprise their milestone “Aja” LP the following year, the two songwriters watched the Bette Davis classic, “All About Eve,” which tells the story of an ingenue who manipulates her way to stardom. “Unlike Eve, the main character in our song doesn’t become a star at all but has starlet fever,” Fagen explained years later. “On her way up, she ditches her boyfriend, but he continues to hang around. All the lyrics are from his perspective, and he’s ambivalent, but he’s convinced there will be a karmic reckoning coming: ‘Peg, it will come back to you.’ He’s thinking that her career will tank, and she’ll end up in some cheesy 3-D film or in someone’s favorite foreign movie, which would be a far cry from her original aspirations.” At that point, Fagen and Becker had become meticulous perfectionists in the studio, and they had seven different guitar players come in to try their hand at the solo during the middle break. They finally settled on Jay Graydon’s work, which was actually spliced together from three different takes. Michael McDonald provided the distinctive harmonies, overdubbed three times. “We felt we’d achieved a special simplicity with that song,” Fagen added. “I think it’s easy on the ears.” As the album’s first of three hit singles, it reached #11 in the fall of 1977.

“Doctor, My Eyes,” Jackson Browne, 1972

In 1969, Browne, then just 21 and struggling to write songs on his grandfather’s old upright piano in the Echo Park area of L.A., had a problem. “During the writing process, my eyes became infected and badly encrusted,” he noted. “I could barely see until I went to the doctor and got some medicine, but it took a while for my eyes to return to normal. That was the initial inspiration for the song’s lyrics. But that’s not much of a song, so the eye issue became a metaphor for lost innocence and having seen too much: ‘Doctor, my eyes, tell me what is wrong, was I unwise to leave them open for so long?‘ It became about a slow erosion of idealism.” The first draft of “Doctor, My Eyes” was rather bleak, he recalls, with the narrator adopting an almost fatalistic point of view about life. By the time he recorded the song for his self-titled debut LP in early 1972, Browne had given it a decidedly upbeat arrangement and tempo, driven by lively drums and congas, with killer harmonies by David Crosby and Graham Nash, all of which served to make the still-downbeat lyrics more palatable: “My eyes have seen the years, and the slow parade of fears without crying, /Now I want to understand.” As one reviewer put it, “As with many of Browne’s song, ‘Doctor, My Eyes’ is essentially a spiritual search — no preaching, no conclusions, just searching.” The song put him on the map, becoming a surprise hit at #8 in the spring of 1972.

“Rapture,” Blondie, 1980

Singer Debbie Harry and guitarist Chris Stein had found success in the late 1970s as founding members of Blondie, one of the best of the New York-based bands specializing in the punk/New Wave genres then in vogue. “We had become good friends with Bronx-based hip-hop artists like Fab 5 Freddy Brathwaite,” said Harry, “and he invited us to a rap event one night in 1978. We were so impressed and excited by the skill of the emcee’s rhymed lyrics delivered in a freestyle way. We went to several more of these events, jammed into this room with a writhing mass of humanity, dancing and pressing against each other as Chic-inspired disco music played. It wasn’t long before we decided to try our own rap song, and Chris thought it should be called ‘Rapture.'” He came up with the guitar and bass line, and they teamed up on lyrics for the verses based on what they’d seen in The Bronx: “Toe to toe, dancing very close, /Barely breathing, almost comatose, /Wall to wall, people hypnotized…” The band recorded the basic track in the studio, including the verses, but the rap section hadn’t been written yet. Harry and Stein took 20 minutes to figure it out, using Stein’s affinity for B-movies and science fiction imagery (“The man from Mars”), and they recorded it in two takes. The drummer found some tubular bells in the studio and added them to the mix for a haunting, ethereal feel. It became their fourth #1 single in 1981. “It was an homage to what I saw, and to a form that was exciting for us,” said Harry. “I probably should’ve worked on it a little more. It was a bit too sing-song-y and childlike, but it evolved in live performances.”

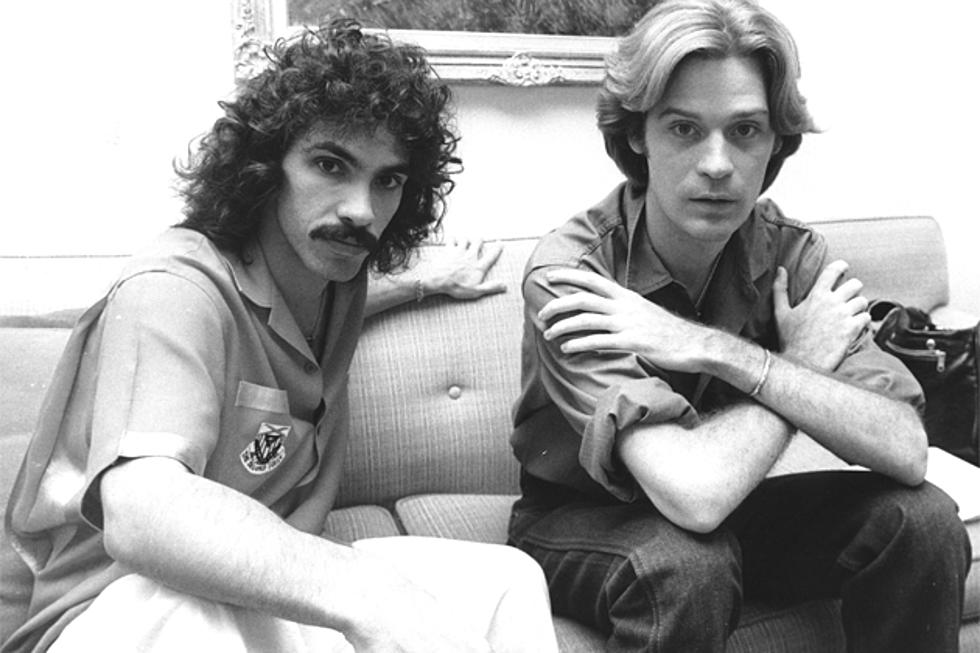

“She’s Gone,” Hall and Oates, 1973

One of this Philadelphia duo’s finest moments, and indeed, one of the great “blue-eyed soul” songs of all time, “She’s Gone” is a classic example of how songwriting partnerships can work. John Oates had a New Year’s Eve date who never showed up, and he was feeling bummed out. “I sat on the sofa strumming my guitar,” he revealed, “and came up with a folky refrain about being stood up that I thought might make a good chorus: ‘She’s gone, I better learn how to face it, /She’s gone, I’d pay the devil to replace her, /She’s gone, what went wrong?’ When he played it for Daryl Hall a couple days later, Hall was intrigued, but felt it sounded like a Cat Stevens song. “I’m much more R&B,” he said, “so I suggested, ‘Let’s try it in another groove.’ I sat down at my electric piano and played the keyboard lick you hear on the intro, and I started hearing the way the song could really build dramatically.” Hall’s first marriage was dissolving at the time, so the “she’s gone” concept struck home and inspired some verses of his own. “Everyone was telling me not to worry, that I was going to be all right,” said Hall, “but none of that was helping,” which prompted these lines: “Everybody’s high on consolation, /Everybody’s trying to tell me what is right for me.” The song was largely ignored on its first go-around in 1973, but after H&O had the #1 hit “Rich Girl,” the label re-released “She’s Gone” in 1976 and it peaked at #7. It’s been covered by R&B artists like Tavares, Lou Rawls and The Bird and the Bee.

“Hello It’s Me,” Todd Rundgren, 1968/1972

Written in 1967 about a painful high school breakup, “Hello It’s Me” was Rundgren’s first attempt at songwriting at the tender age of 17. He had founded the band Nazz, who played cover songs, “but if we wanted a record deal, we needed original material. The chords and melody to this song came pretty quickly, but I wasn’t sure about lyrics yet.” Eventually he decided to focus on a high school crush, a girl he had been crazy about, “but her father hated me on sight, probably because of my long hair, and she was forbidden to see me anymore. I adored her and was heartbroken about it.” When he was writing the lyrics the following year, “I turned the story around so instead of being the victim, I was breaking up with her, which gave me a little power and allowed me to imagine how I might have done things differently. To ease the blow, I wrote a bridge about why the breakup was good for her: ‘It’s important to me that you know you are free, /’Cause I never want to make you change for me…’ I think it’s how I would have wanted to be let down.” Nazz recorded it first on their 1968 debut as a slow ballad, which wasn’t quite the way Rundgren envisioned it. By 1971, he had embarked on a solo career, and as he was putting finishing touches on his astonishing double-album debut, “Something/Anything?”, he updated “Hello It’s Me” with a bouncier pop arrangement. He re-released it as the third single from that album, and it reached #5 in 1973, the commercial high point of his lengthy career.

**************************